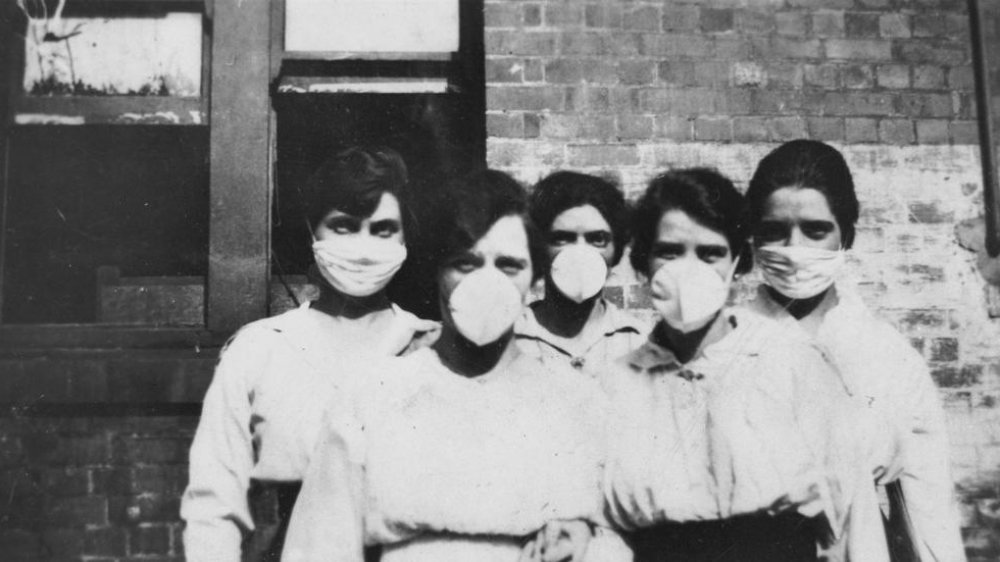

The Spanish Flu Was Worse Than You Thought

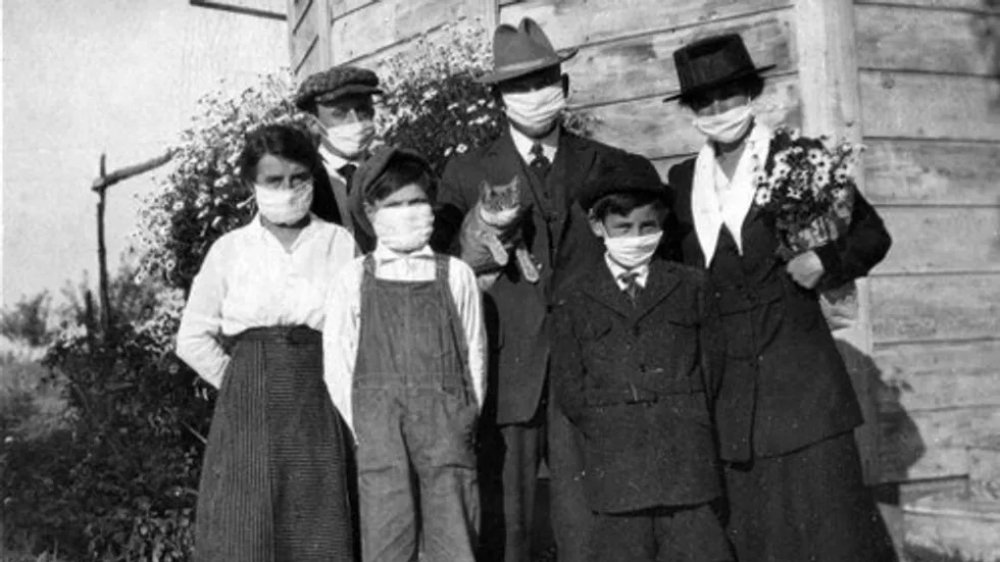

Every year in the US, flu season hits. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, cases of the flu usually reach their peak between December and February, but basically, everyone's in for months of misery. Small consolation? It's not as bad as the Spanish flu. History says that one was more than a little different — it kicked off in the spring of 1918 on the tail end of World War I, and it was downright brutal. And there's one thing that should be cleared up right away — no, it didn't start in Spain, even though in some places, it was somewhat ironically referred to as the Spanish Lady.

Throughout the war, the media was heavily censored on both sides. Word of the illness didn't get out... except in Spain, which had stayed neutral through the conflict. And in Spain, it wasn't just uncensored, it was high-profile: it even infected King Alfonso XIII. Countries around the world started hearing all of this frightening news out of Spain and assumed that it was ground zero for the flu. (And in Spain, they didn't call it the Spanish flu — it was the French flu, because of course it was.)

Regardless of where it started and who talked about it first, it spread very, very fast. And it was way worse than you might expect the flu to be.

The Spanish flu killed way more than you'd think

The Spanish flu kicked off at the end of World War I, and shockingly, it was responsible for more deaths than the conflict known as the Great War. History says somewhere around 17 million people were killed during the war, and while the official death toll attributed to the 1918 pandemic varies greatly, it's thought there were around 500 million people infected. At the time, that was about a third of the world's population. And the dead? It's generally estimated somewhere between 20 and 50 million people, although studies published by PubMed suggest that even that 50 million number might be "as much as 100 percent understated."

When you start talking about numbers that big, they are hard to fathom — so let's put it in some perspective. Just in 1918, death was so widespread that the average American life expectancy dropped 12 years (via History). And let's take that 50 million number. That would be like the US, in 2020, losing the entire populations of Georgia, North Carolina, Wisconsin, Colorado, Minnesota, South Carolina, Mississippi, New Mexico, Nebraska, Idaho, Maine, West Virginia, and Wyoming (via World Population Review).

If you want to talk global, 50 million is roughly the entire population of countries like South Korea, South Africa, Argentina, and — ironically — Spain. And remember, that 50 million number might be conservative.

It wasn't the normal flu

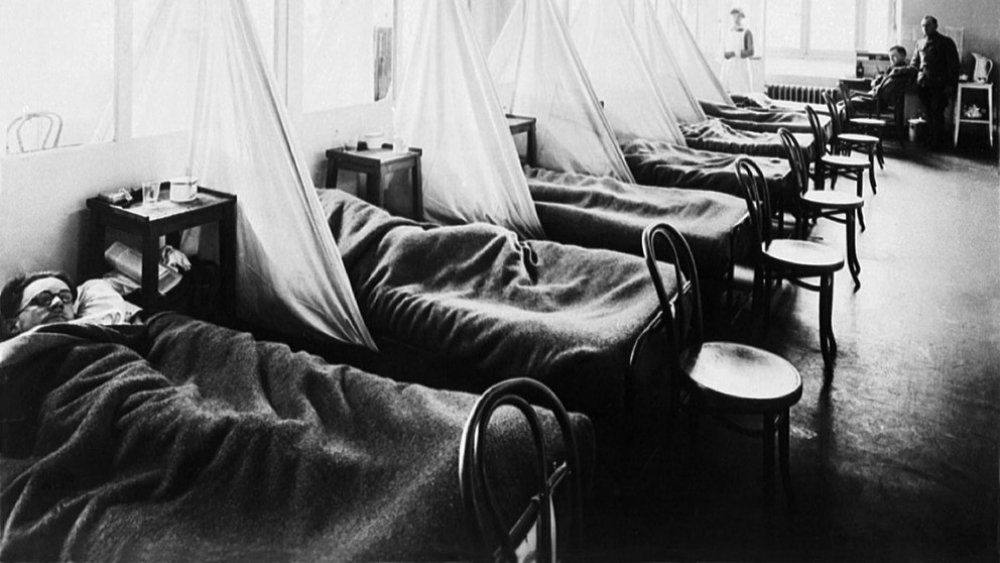

The normal flu isn't fun, and the CDC says that the most common symptoms include fever, cough, a sore throat, congestion, and body aches. The 1918 flu was very, very different.

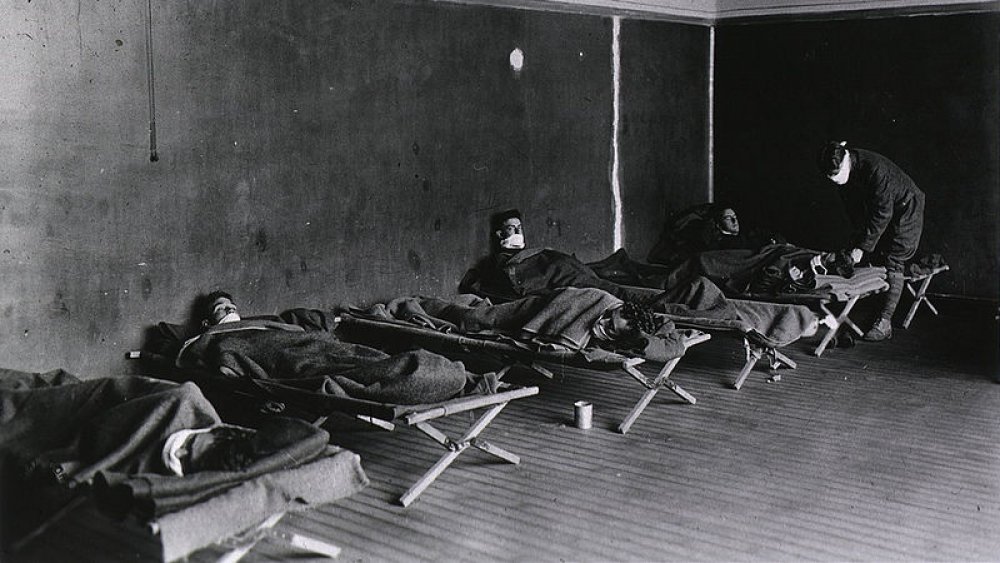

National Geographic says that the Spanish flu hit victims unthinkably fast, with stories told of people who woke up feeling a little under the weather, and then dropped dead as they made their way to work. Symptoms generally started with a fever and difficulty breathing, which would become such a struggle the victims would turn bluish-purple — a condition the Wellcome Collection calls cyanosis. The lungs would fill with fluid, and when the hemorrhaging started, they'd fill with blood, too. That would lead to what Nat Geo describes as "catastrophic vomiting and nosebleeds," with many victims drowning in the blood and fluids.

Even the most common symptoms were nothing short of agonizing. History says victims were crippled by blinding headaches and suffered from coughing fits so intense that they tore muscles. Skin turned black, blood leaked from orifices, and it was a terrible way to die.

The Spanish flu was 'deadliest' to a lot of demographics — including the breadwinners

When journalist Laura Spinney researched and wrote Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World (via the World Economic Forum), she uncovered some shocking things that had been long forgotten. Most of the time, the flu is most dangerous to the very young, the very old, and the already ill. But those most vulnerable to the 1918 flu were those between the ages of 20 and 40. Why? Research done by Michael Worobey, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Arizona (via The Atlantic), found that it was this demographic of people who had never been exposed to a similar strain of the flu before and had no previously existing immunity.

And that created a domino effect of problems, which were further complicated by a difference in the vulnerability of men and women. Research published by the US National Library of Medicine found that men were much, much more likely to die from the Spanish flu, partially because they were much more susceptible to tuberculosis — the combination of TB and the flu was particularly deadly.

And with that combination of circumstances, the Spanish flu devastated entire families. When men in the prime of their lives started dying, families lost their breadwinners. And at the time, there was little to no social welfare system in place, leaving families that were mourning the loss of their loved ones to wonder how they were going to survive without them.

Orphaned by the Spanish flu

The 1918 flu left its mark on those who survived, too, including children left as orphans, and the elderly who suddenly had no one. Take the case of Wales, a small town in Alaska. Indian Country Today says that in 1919, the 120 flu survivors included 40 orphaned children. Among the orphans was Joe Senungetuk's mother. He said, "My mother, who was found in her parents' sod house, was just a toddler. [...] And my mother... was not OK, in that she was found suckling on a dead mother."

It's not clear just how many children were left in that same terrible situation, but the snapshots history does remember are very telling. According to the BBC, there were around 500,000 "flu orphans" just in South Africa, and according to a 1918 Washington Times article uncovered by Ghosts of DC, the problem of how to care for all of that city's orphans was "more difficult today perhaps than ever before in the history of the National Capital." Remember, too, the size of families at the time. The death of parents meant children — sometimes seven, eight, or more of them — were left to hope for the kindness of relatives or strangers.

The elderly, too, were in a sense "orphaned" by the Spanish flu. When sons and daughters died, they had no one to care for them in their final years. Just what happened isn't clear, but journalist Laura Spinney found evidence (via the World Economic Forum) that Sweden dealt with the problem by moving their senior citizens into workhouses.

Survive the war... succumb to the flu

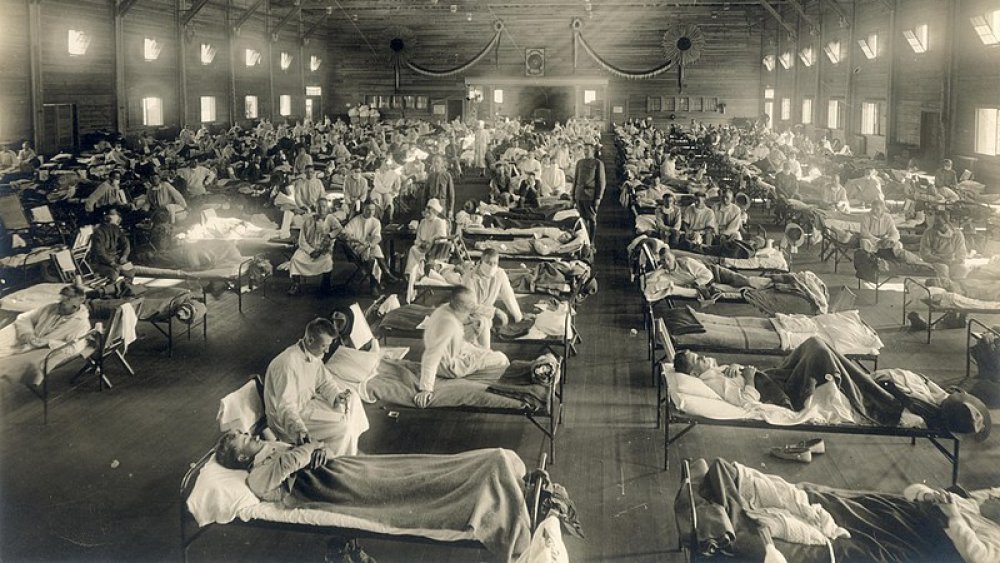

War is hell, and when 1918 rolled around, it brought with it a double whammy. John Mathews, Honorary Professorial Fellow of the University of Melbourne, says (via The Conversation) that the flu and World War I overlapped by about nine months. And war — particularly the crowded, unsanitary conditions of the trenches, troops ships, and barracks— was pretty much the perfect breeding ground for the flu to multiply and spread.

More than that, the soldiers fighting shoulder-to-shoulder with each other were from all parts of the world. And when the end of the war came, those soldiers scattered, back to their homes and their families... and they carried the flu with them.

The war ended in November of 1918, and according to the BBC, it was as soldiers returned home — reunited with their friends and family, their wives, girlfriends, and children — that the virus really started to spread. And that's awful: reunions which should have been happy, reunions that had been hoped and prayed for over the course of weeks, months, and years, were suddenly had under the looming specter of death.

Racism contributed to the spread of the Spanish flu

The Spanish flu didn't start in Spain, but historians haven't been all that certain where it did start. According to National Geographic, there's a theory — one described as "about as close to a smoking gun as a historian is going to get," by Lehigh University historian James Higgins — that says it started in China, and spread for a terrible reason.

Historian Christopher Langford uncovered a few pieces of intriguing evidence, starting with the fact that in 1917, people living in northern China suffered from a widespread respiratory illness that was later identified as having symptoms identical to what was then being called the Spanish flu. He also found how it may have been spread — by 25,000 Chinese Labor Corps workers who were sent work in Europe. The idea was that by increasing the workforce available on the home front, more men would be free to head off to war. Among those sent to Europe were 1,899 men from Weihaiwei... who headed there via Canada, in spite of the fact that widespread plague had put a stop to recruiting workers from the area.

Further digging turned up medical records indicating more than 3,000 workers in the program were sent to quarantine after reporting flu-like symptoms. But their concerns were largely ignored: they were given castor oil for their sore throats and sent back to work. Why? At the time, it was believed they were simply lazy, and trying to get out of work.

The Spanish flu wasn't actually more deadly than other flu viruses

It'd be at least a little comforting to think of the Spanish flu as something of a fluke, and a super-powerful, more-potent-than-normal virus. But according to Richard Gunderman, Chancellor's Professor of Medicine, Liberal Arts, and Philanthropy from Indiana University (via The Conversation), it actually wasn't: "[...] the virus itself, though more lethal than other strains, was not fundamentally different from those that caused epidemics in other years."

That's... terrifying. So, what happened here? Research suggests that many people who died, didn't die from the flu... not exactly. The flu — coupled with things like poor diet and nutrition, along with the unsanitary conditions found in cities and on the front lines alike — actually made people more susceptible to other things. A study published in The Journal of Infectious Diseases found that "secondary diseases" like bacterial infections were responsible for about a third of deaths, while respiratory failure still bore the majority of the blame.

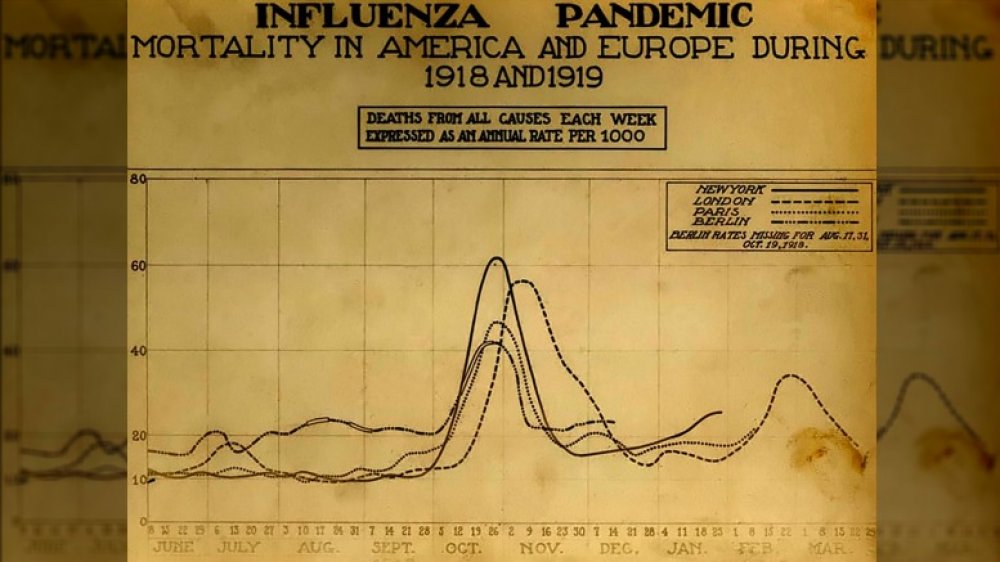

Also terrible? The virus hit in three waves, and the first was actually something of a warning shot. The second — which came in October to December of 1918 — was far deadlier, and the third — which didn't happen until spring of 1919 — also killed more people than the first.

Native American tribes were particularly hard hit

Some communities were particularly hard hit by the 1918 flu, and that included America's indigenous people. A 2014 study from Brigham Young University (via Indian Country Today) found that Native Americans were about four times more likely to die than those outside of their communities. That was the case globally, too, with researchers noting, "Indigenous people all over the world were especially vulnerable; some were not just decimated but sometimes annihilated."

Research from the University of Nebraska found that while mortality rates varied greatly among Native American tribes, many shared a wide range of circumstances that made them particularly vulnerable, like poverty, malnutrition, a higher instance of other diseases, and a lack of access to medical care and pharmacies.

There was also a cultural aspect, too. Navajo beliefs dictated that the sick should be attended by a medicine man and be positioned at the center of a ceremony that included close friends and family — bringing others in contact with the disease. There was also a belief that should a person die in a home, their spirit may become attached to that place — so, they were often moved out into the elements and without the benefit of shelter, quickly succumbed.

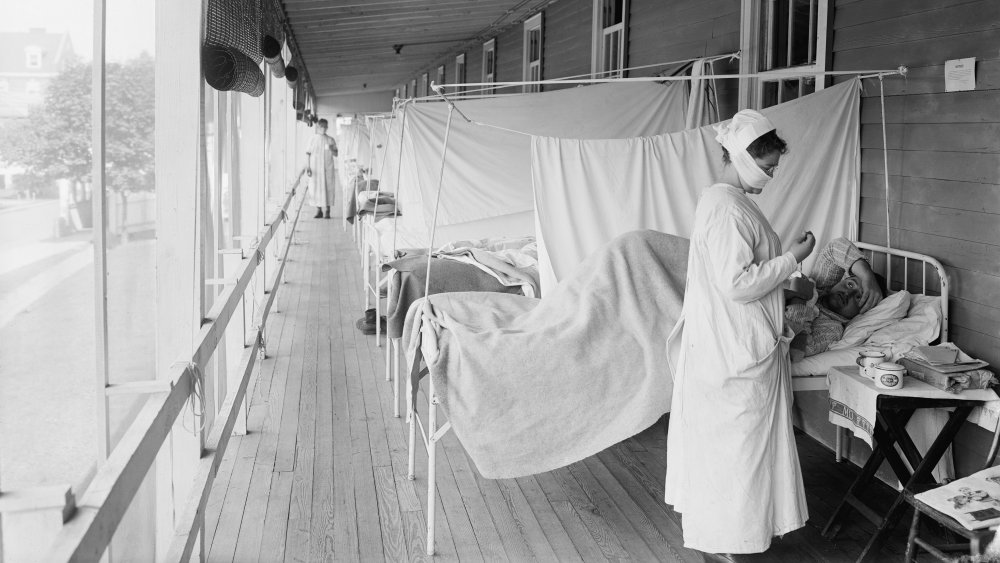

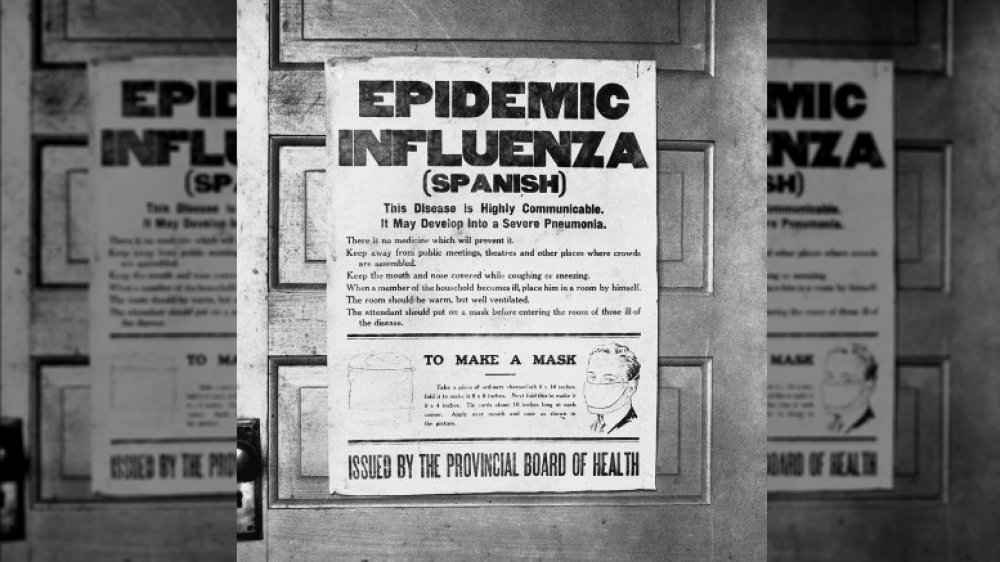

Government missteps made the pandemic much worse than it needed to be

Governments were ill-prepared to deal with the spread of the 1918 flu, and sometimes, they made it much, much worse. Let's look at Philadelphia. According to National Geographic, their handling of the disease was among the worst in the country, and it showed — after 24 weeks, they were suffering 748 deaths per 100,000 people.

Philadelphia confirmed their first case on September 17, 1918. While they immediately started a campaign to discourage people from spitting, coughing, and sneezing in public, they still didn't shut down public areas like other cities did. In fact, just 10 days later, they held a parade with 200,000 people in attendance. It wasn't until October 3 that places like schools and theaters were closed, and by then, it was already out of control. Cases rose by the tens of thousands, compared to New York City, which quarantined people early and ended with the lowest death rate on the East Coast.

Other cities that went the same route as Philadelphia included Pittsburgh (807/100,000), New Orleans (734/100,000), and Boston (710/100,000). You can compare that to Minneapolis, who reacted quicker, imposed harder restrictions, and left their social distancing measures in place for longer: they had only 267 deaths per 100,000. Cities with similar outcomes included Indianapolis (290/100,000) and Milwaukee (359/100,000). Bottom line? People were at the mercy of their local governments.

The town that lost all but eight people

In hindsight, it makes sense that the Spanish flu would spread so fast through so many countries, but the strange thing is how it touched so many remote cities and villages, too.

One of those places is the remote Alaskan town of Brevig Mission. At the time the Spanish flu was sweeping across the world, there were 80 people living in the remote outpost — and 72 would contract the flu, and would be dead within five days of contact. According to Encounters Alaska, it's now believed the virus spread from mail ships to dog sled teams and finally into communities — communities that were, by nature, very close-knit and highly cooperative. Tragically, that served to spread the virus even more thoroughly.

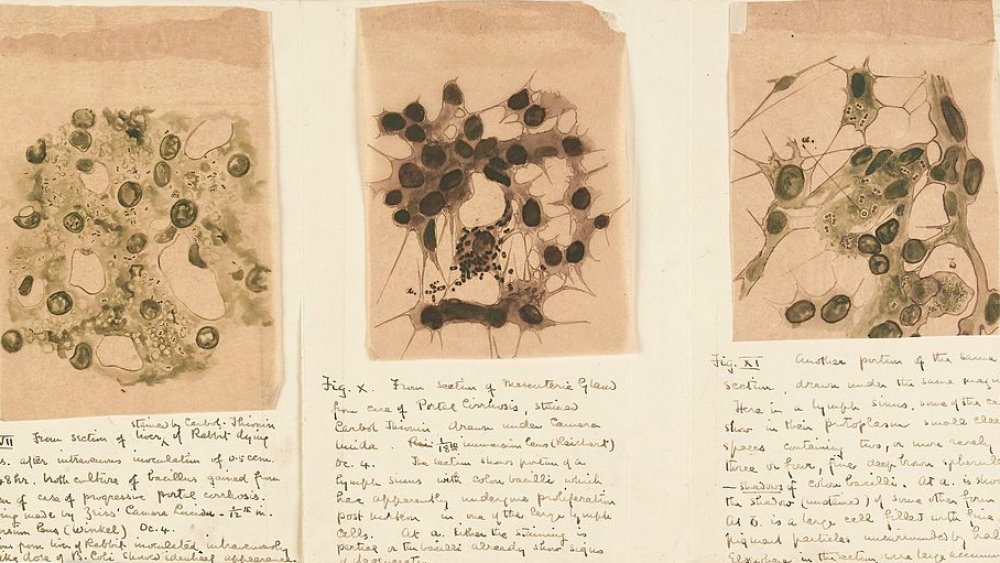

The results were devastating. Many of these people had their own culture and their own way of life, and the deaths of the majority of their population meant the deaths of their entire communities. There is one positive thing to come out of Brevig Mission's devastation, though: a Swedish microbiologist was able to get permission to reopen the mass graves in 1951 — preserved by the permafrost — and extract lung tissue and samples of the virus. Over the course of decades, his work and the advancement of scientific research made it possible to isolate the virus and develop a vaccine... that was complete in 2005 (via Anchorage Daily News).

Some of the 'cures' were downright bizarre

Lapham's Quarterly says that some advice on avoiding the flu was good: don't use common drinking vessels, cover your mouth when you cough, and awesomely, "Avoid Worry, Fear, and Fatigue," which is sage wisdom all the time. Then there were the harmless cures, like the idea that eating more onions might help keep the disease away. But many more were less benign.

Strychnine, belladonna, chloroform, morphine, and kerosene were all touted as legitimate medicines for treating the flu, and that last one? Kerosene would be dripped onto a sugar cube, then fed to the afflicted. In some cities, turpentine took the place of kerosene, but the sugar cube was the same. There was also a belief that the air itself was dangerous, and that led to people sealing themselves inside their homes... sometimes, a little too well. At least one person — an Italian woman — made her house so air-tight that she suffocated.

Then, there was liquor. Whiskey in particular was believed to be a massive cure (although one cure from Nova Scotia was the "do not try this at home" remedy of drinking 14 gins in a row, as fast as possible.). Medical professionals tried to derail that belief, but it was difficult — especially when bartenders were coming up with drinks like the whiskey-and-rum cocktail called the Corpse Reviver.

The little-explored link between the flu and brain diseases

The Spanish flu eventually faded away, taking with it millions and millions of people. But here's the thing — the impact of the 1918 flu lasted much, much longer than that, and we only have hints about just what's going on here.

According to Penn State University's Greg Eghigian, PhD (via the Psychiatric Times), researchers looking at those who survived the Spanish flu found some surprising things. The number of patients admitted to hospitals with a diagnosis of a mental disorder rose by an average annual factor of 7.2 in the six years after the outbreak. Also, survivors struggled with a laundry list of problems, including depression, sleep disturbances, and difficulty concentrating. Other doctors reported seeing an increase in things like degenerative nerve conditions and meningitis. While there was never any definite causality established, we're going to have to fast forward a bit for the rest of the story.

According to The Scientist, new interest in the connection between the flu and neurological diseases was sparked when Richard Smeyne, a neurobiologist with St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, recognized the symptoms of Parkinson's in a duck that had been infected with the H5N1 bird flu. He started looking into the idea that exposure to the flu could leave survivors more susceptible to neurological conditions, and suspects there's a link — although more research needs to be done.