What Life Was Like For Trappers In The Wild West

What was life like for trappers in the Wild West? In a word, short — at least for the vast majority of bold mountain folk who dared to venture forth into unknown lands to bag some sweet pelt action while tweaking the unforgiving nose of Mother Nature.

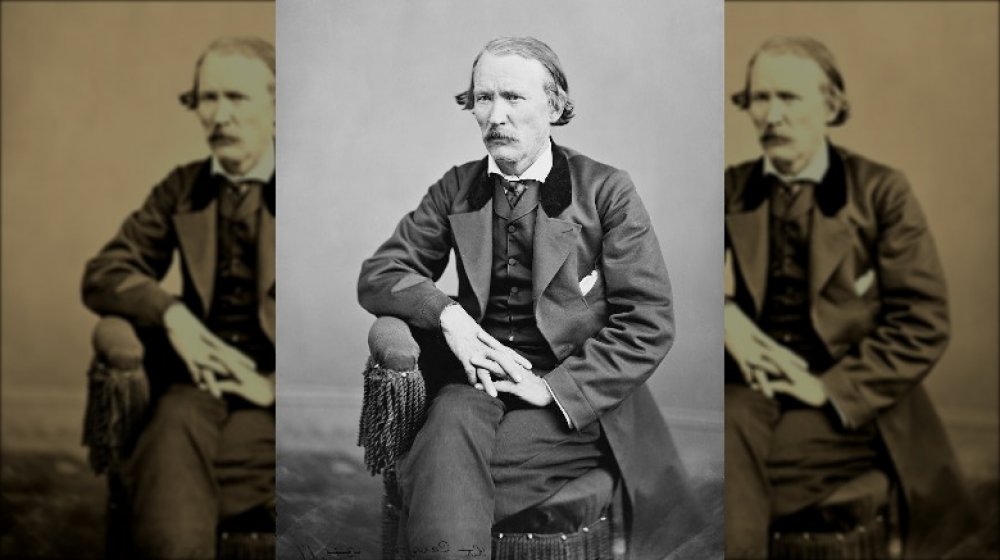

In a True West Magazine article, "The Life of a Fur Trapper," an account is given of a wizened old fur trapper, Antoine Robidoux, who claimed that of 300 trappers who had been active throughout his career, only three were still living. Another trapper claimed that in a single year, 160 trappers went out to bag pelts between Arizona and New Mexico. Only sixteen returned. Now, exaggeration is a thing. And trappers like Kit Carson were as guilty as any of slathering a thick saccharine layer of mythologized heroism over the dried toast of a difficult and punishing existence. But still. All known accounts of the lives of trappers in the Wild West echo the same basic premise that a lot of stuff could, and would, get you extremely dead.

Bears, of course, were a problem — particularly if you were unfortunate enough to encounter one that was hungry, wounded, or otherwise perturbed by the aborted hunting efforts of another trapper. But starvation and exposure to the brutal elements were as effective at finishing trappers off as any enormous furry thing with big teeth and a bad disposition. Reports of famished trappers enjoying a Wild West diet of ants and bugs to stay alive are commonplace. According to the True West Magazine article, they may even have resorted to eating non-essential bits of their poor mules when desperate for calories.

A surprisingly regimented existence

The dangers nature posed were only part of the peril, however.

Trappers were constantly negotiating with indigenous tribes, and one another, to ply their trade. And of course, by definition, these people were competing over limited resources that were often difficult to come by. Not surprisingly then, the North American Fur Trade as filled with hostilities and violence between people, which could just as easily send a trapper to his grave as hunger or critters.

It's easy to imagine that the life of a trapper was solitary and unfettered by the oppressive rules of society. For most trappers, this was far from the truth. Most trapping work took place through organized and hierarchical collectives, not unlike the military. Mess groups were formed, all reporting up to a veteran trapper, known as a "boosway" (a distorted version of the term Bourgeois, according to History and Culture of the Boise Shoshone and Bannock Indians). These brigades made the process of trade easier, but they also imparted some measure of strength in numbers, as a trapper surrounded by a hundred or so other equally smelly and life-hardened grizzly hunters probably had a slightly better chance of survival than going it alone.