Things The Vikings Couldn't Live Without

The Nordic countries at the top of Europe — Sweden, Denmark, and Norway — are often praised for their "sustainable businesses" and celebrated for the "pragmatism that defines many Scandinavians today" (via The Viking Code). What may not be common knowledge, however, is just how deep-rooted these values are — going all the way back to the Viking age. As the BBC notes, this period in history "covers the period from the 8th Century until the 11th Century AD."

While Norse culture has been brought back into the mainstream thanks to shows like Vikings and The Last Kingdom, our imaginations have been left to run wild with stories of these pagan pirates pillaging settlements, enslaving village folk, and desecrating churches. While they undoubtedly may have lived by some brutal methods, there are still many false facts about these "heathens" that everyone seems to think are true.

Life as a Viking definitely wasn't easy, but there was much more to it than legend makes it seem. "Days were spent rowing longships, creating intricate art, or telling stories about duels between gods and giants," writes the BBC. While there are certainly obvious aspects to Viking life that we are all aware of, what many people don't know of are some of the things that these fierce warriors valued most. Here are the things that the Vikings couldn't live without.

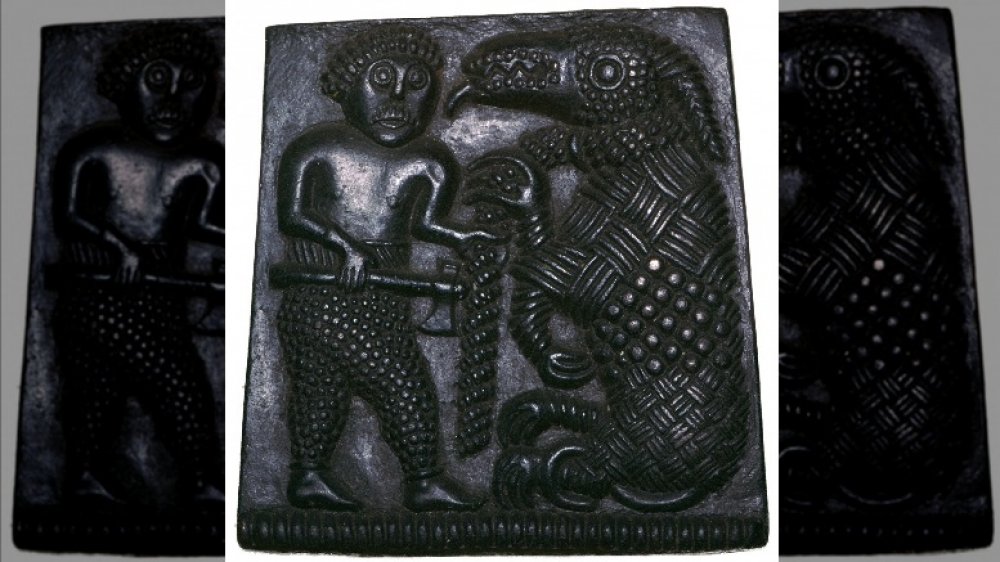

Weapons were vital for a Viking warrior

When you think of the Vikings, the first thoughts that come to mind are that of ferocious fighters — sword and shield in hand, leaping off ships, and immediately into combat. While part of this may be valid, you'd be surprised to find out what exactly was the most accessible weapon.

According to the National Museum of Denmark, weapons were "indispensable on plundering raids and for self-defense" — a crucial part of Viking lives. While it's easy to assume that swords would have been the primary go-to, they were actually "the costly weapons of the elite" while "axes and lances were affordable to the warriors of the broader population."

By the late Viking period, laws dictated that "all free men were expected to own their own weapons," with many owners even decorating their armaments "with inlays, twisted wire and other adornments in silver, copper and bronze" (via the BBC). Because of a Viking's deeply-rooted religious beliefs and desire to head to Valhalla in the afterlife, many would choose a bloody death on the battlefield, hoping to appease Odin, "Father of the Slain." As the BBC explains, "all who fall in battle are [Odin's] adopted sons," and "knowing they might end up [in Valhalla] encouraged them to embrace the dangers of the battlefield."

Ships were crucial, and not just for terrorizing faraway towns

While spring months focused on peaceful tasks such as planting crops and farming, a Viking summer primarily consisted of exploring and raiding towns (via the BBC). So, how were the Vikings so successful at plundering? Well, it couldn't have been done without the help of their primary mode of transportation: ships.

As the BBC explains, their marine technology was "revolutionary," with these ships "[establishing] them as world leaders." (Seriously, who wouldn't be terrified seeing these nautical monsters rolling up on shore, ready to raid?) As Royal Museums Greenwich further reveals, these longships "were all made from planks of timber, usually oak, overlapped and nailed together," then made watertight by sticking "wool, moss, or animal hair, mixed with tar or tallow," in between the planks. To further drive their point across that they should be feared, Vikings would adorn the front of the ships with carvings of animal heads, such as dragons or snakes, for example.

While longships are definitely the most well-known, these Norse warriors also used cargo vessels "to carry trade goods and possessions." Because Viking ships had no interior shelter, voyages were saved solely for summer, and if they were stuck at sea, "They'd take the sail down and lay it across the ship to make a tent to sleep under." Hardcore, huh?

Forget dogs, bears were a Viking's best friend

The Ancient Egyptians adored cats, while 18th-century nobility preferred lapdogs, so what sort of animal did the Vikings enjoy keeping as pets? Sure, felines were also present on seafaring journeys (according to Science Mag, they were raised "for their warm fur and to control pests"), but as one would imagine, Scandinavian folk enjoyed a much more ferocious beast — the bear.

Alongside fellow exotic animals such as hawks and falcons, bears were common pets for the Viking people (via Ancient History Encyclopedia). Brown bear cubs, in particular, "would be taken when young and raised by the people of a home to be fully domesticated. These bears were then known as 'house bears.'"

If you thought that was wild enough, brown bears weren't just the only option. According to Viking Voyagers, the Vikings of Iceland and Greenland also domesticated polar bears, "but they were seen as an extravagant pet." These bears would then be traded to "European kings for favor and fortune in return." Eventually (and unsurprisingly) enough, "these bears became more of a nuisance than anything else," with "large fines" bestowed upon those who allowed their bears to damage property.

Children were important as workers in the Viking community, too

It's easy to be under the impression that Viking men were fierce warriors who spent their days raiding villages while women tended to farms, but what exactly did their children do? As it turns out, they were an essential part of Viking lives, as tots "under the age of 15 made up nearly half of the population" (via Hurstwic).

The average life expectancy of the Norse population during this period was "about 20 years," so no time would be wasted when it came to integrating youths into society, treating them "as small adults." That meant responsibilities: "They were expected to work and to contribute to the productivity of the farm."

So, was there any time for play? Well, kind of. As Exploring the Vikings reveals, there weren't that many toys available, and those that did exist were "miniature versions of adult objects such as ships, weapons, and tools." Instead, "bold, independent behavior was prized in children," with tales of rebellious kids met with praise (via Hurstwic). That being said, by today's standards, "we might think such behavior to be borderline criminal or psychopathic in nature." All work and no play makes Viking children kind of crazy, hey?

The Viking religion trumped everything

Much like the importance of Christianity to the Anglo-Saxons, the Vikings also held religion in the highest regard. As Life in Norway perfectly summarizes, "it was seen as [a] lifestyle rather than religion." What's more, unlike Christianity, this old Norse paganism wasn't written down and was instead recited orally, sometimes during rituals.

Thanks to popular culture, a common misconception about the Vikings is that they entirely rejected Christianity. And while they did conduct raids of churches and monasteries (these buildings were always heavily stocked with wealth), they were also quite curious about this new religion. As the BBC notes, "when they settled in lands with a Christian population, they adopted Christianity quite quickly." After all, why wouldn't they? Unlike the Anglo-Saxons, the Vikings worshiped countless gods, "The best known is Odin, God of Wisdom, Poetry and War. Odin's son Thor — the God of Thunder — and the goddesses of fertility Freyr and Freyja are other notable names" (via Life in Norway). These gods were usually represented on Viking bodies, especially through jewelry, such as Thor's Hammer, which was a common option.

As the Vikings further settled close to their Christian brethren, they would start to mix their cultures through marriages, with their children growing up "in partially Christian households." This led to a "peaceful co-existence," as portrayed on "the coinage of Viking York," which showcased both cultures, carrying "a deliberate message that both paganism and Christianity were acceptable."

They had their own Viking compass that guided them day and night

While their ships were undoubtedly the most powerful tool during raids, how did the Vikings know exactly where to go? Well, with their sun compass, of course. As the Shetland Amenity Trust's Davy Cooper explained to the BBC, this contraption was "a very simple circle with a pin in the middle," which helped guide these Norse warriors "according to the height of the sun and time of day." So, was it foolproof? Not quite. "They tended to get blown places accidentally, but they knew what direction to sail going back," revealed Cooper, adding, "That meant they could find the place again, and they could tell someone else how to find it."

The sun contraption, however, wasn't the only form of a compass that the Vikings used, as they also discovered the benefits of crystals. "They used a crystal that, when turned in a certain direction it goes dark, and when it goes in another direction it goes light," explained Cooper to BBC. "So when turned to a light source they discovered that it even worked in fog if they knew where the sun was – meaning they could figure out what direction they were traveling in."

Based on the "skylight polarization patterns" caused by light hitting the crystals (or calcite stones), the Vikings could navigate even at twilight, despite not being able to determine the physical position of the sun in the sky (via The Royal Society).

'The Thing' ruled all

When you think of the Vikings, you don't exactly think of them as lawful people — yet they had a set of rules that are strikingly similar (albeit basic) to those in modern cultures, such as the concepts of not killing or stealing. "A lot of it related to property and respecting property," explains the Shetland Amenity Trust's Davy Cooper to the BBC. Viking law was mostly oral (or written in rune), so how exactly were these orders upheld?

"The Thing" was a gathering set in a place where "guidelines and rudimentary laws were discussed," reveals BBC, adding that it's at the Thing that "alleged criminals would be tried by a group of their peers," with guilty verdicts resulting in fines or even banishment. "There was a local Thing, which was a local council," describes Cooper, adding, "Then there was [...] a Shetland-wide Thing. Local Things would send representatives to that. Ultimately there was the King and court in Norway." Interestingly enough, these early councils can be considered the framework for modern-day judicial systems.

The Thing wasn't solely used for criminals, however. As History on the Net details, "community decisions and new laws" were also made. These meetings had much more of a "festive atmosphere," where there would be food and water available for everyone, along with "barrels of ale and mead," and an opportunity for "gossip [to be] exchanged."

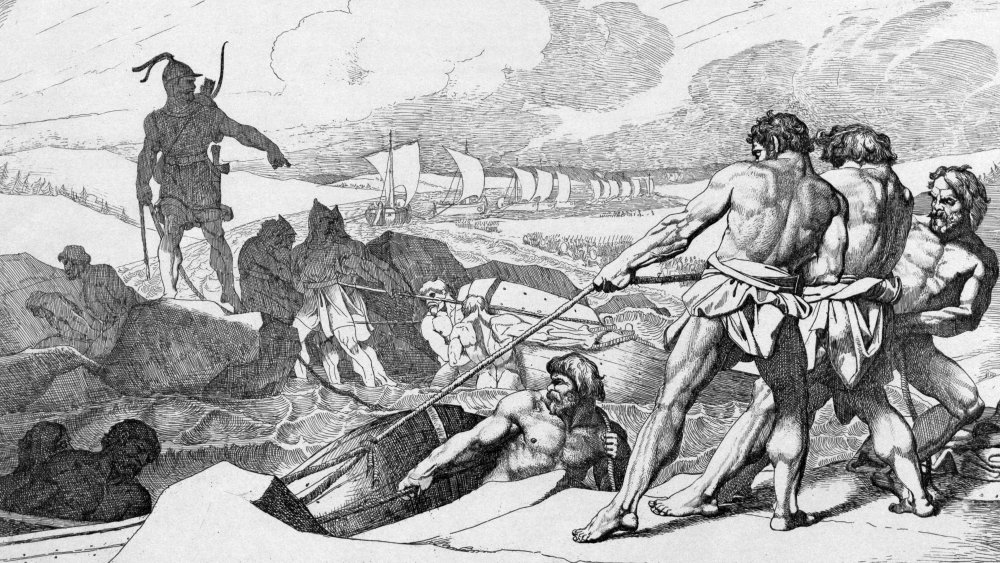

Slaves were essentially a form of currency

Although it seems shocking by today's standards, "Slaves or thralls were amongst the most important commodities traded by the Vikings" (via the National Museum of Denmark). Scandinavians collected their thralls throughout Eastern Europe and the British Isles, then either trading them for various products or alternatively using them for "manpower for the great building projects of the Viking Age."

While the concept of slavery is undoubtedly cruel, some female thralls "could live in good conditions and achieve respect. The same probably also applied to male slaves, who were particularly skilled craftsmen." That's not to say that Vikings were exactly kind to them — as National Geographic points out, "among their names were Bastard, Sluggard, Stumpy, Stinker, and Lout." Seen as "cattle," the Norse kept their slaves in "longhouses," where they quite literally slept with other domesticated animals.

The life of these thralls was bleak, and while some of them could have eventually been set free by their owners, it wasn't until the Vikings began dabbling in Christianity that a "decline in slavery" was finally seen (via the National Museum of Denmark).

Honey kept the Vikings warm through harsh winters

When Vikings came back from their various long and harsh raids, they'd love to celebrate with ale or mead. A strong alcoholic drink, it must have had something to sweeten it with, right? As it turns out, honey was the only option available, and it was seen as a "golden treasure" (via Forbes).

Per HistoryHit, the Scandinavians would "wash down" all their meals with these alcoholic beverages, even incorporating honey into their deserts of dried fruit, too. The honeybees would produce "enough honey to keep the warriors imbibing through the long winters," adapting to the colder climates and even exhibiting longer hairs "to help protect [them] from the cold." As such, there was never a shortage of honey, and along with guzzling countless cups of ale, traders even began selling their "liquid gold," along with "tin, wheat, wool, wood, iron, fur, leather, fish, and walrus ivory," all throughout "Europe and as far east as Central Asia" (via the BBC).

It looks like pillaging towns wasn't the only way to gather useful items during the Viking Age, as trading their honey would grant the Norse "materials such as silver, silk, spices, wine, jewelry, glass, and pottery."

Skiing wasn't just a pastime, it was a way of getting around

Tenth century Arab Muslim author, Ibn Fadlan, once mused of the Vikings, "I have never seen people with a more perfect body build" (via the National Museum of Denmark). Sure enough, these fierce Scandinavians had a way to stay fit when they weren't off on summer raids — in the form of various sports.

Hilariously enough, some things never change, such as "the Norwegian obsession with skiing" (via Life in Norway). This deep-rooted desire to go zipping down a snowy mountain traces all the way back to the Viking period, where Norsemen didn't only see it as a "popular form of recreation," but as an extremely convenient way to "get around," too, as revealed by History. Of course, since they had gods for just about anything, the Vikings even worshiped a skiing god, Ullr.

Don't get too comfortable thinking the Vikings were overly keen on après-ski, however, as they also had other sports to keep them preoccupied, such as "Knattleikr." As the journal article "The Viking Ball Game" details, Knattleikr is quite literally translated into "ball game," and while, unfortunately, "no examples of the playing equipment are known to survive," it's still a sport that's been mentioned several times in Icelandic sagas, in particular (via Hurstwic). "Some authors have compared the game to various modern games, including hockey, rugby, lacrosse, and cricket," adding that the game would sometimes even become violent, resulting in blood spilled due to player conflicts.

Viking grooming essentials

The Vikings must have been exceptionally dirty, what with all of the time spent on ships, terrorizing communities, and doing farm work, right? Wrong. Surprisingly enough, according to the National Museum of Denmark, "archaeological finds of 'beauty items' from the Viking period show [...] 'toilet bags' of the Vikings," which were made up of "beautiful patterned combs, ear picks, and tweezers." If that's not enough, "wear marks on teeth also indicate that toothpicks were used."

Interestingly, Vikings actually bathed more regularly than their Anglo-Saxon counterparts, who "believed that the Vikings were overly concerned with cleanliness since they took a bath once a week" (via Medievalists.net) It makes sense then, that Viking men allegedly had "great success" with Viking women, as they were clean and "pleasant smelling," and took pride in combing their hair and dressing well.

While these trendsetting metrosexuals certainly made heads turn with the opposite gender, don't be fooled into thinking they still didn't offer up some traits to scare their opponents, too. As History reveals, "Viking warriors raiding Britain may have filed their teeth to scare their enemies" — a discovery made in 2018 after archaeologists unearthed "deep horizontal grooves" on front teeth, presumably "done by skilled hands." As the National Museum of Denmark reveals, thanks to archaeological finds of skeletons in the modern-day, "the bones show a population that suffered from tooth problems." You think?