What You Were Never Told About The Trail Of Broken Treaties

August 1972. Leaders of the American Indian Movement attending a Sun Dance in Colorado hatch an ambitious plan: they'll crisscross the nation, visiting reservations and stirring the hearts of young Native Americans to action. Building on earlier protests, they'd assemble the best, brightest, and most engaged and storm Washington, D.C., just before the presidential election. What could possibly go wrong?

Oh, only nearly everything. While the Trail of Broken Treaties went smoothly on the road, picking up nearly a thousand protesters along the way before cruising into the nation's capital on November 1, 1972, no plan for massive social change ever survives its first encounter with bureaucracy.

The protest's goal, according to organizer Robert Burnette in a press release, was to peacefully raise awareness of the systemic oppression of indigenous people in the United States. As he put it in Paul Chaat Smith's book Like a Hurricane, "Today, Indian identity is defined and refined by a quality and a special degree of suffering. The Caravan must be our finest hour." To speak out about Native American self-determination, a crushing history of broken promises, and the brutal poverty and inequality experienced by many Native Americans, protesters would go on the move, traveling from the West Coast to the nation's capital to call attention to social justice issues facing Native peoples and demand systemic change. It was a great plan, but as today's BIPOC community knows all too well, it didn't succeed in its efforts to create a socially just America.

The Trail of Broken Treaties was part of a bigger movement

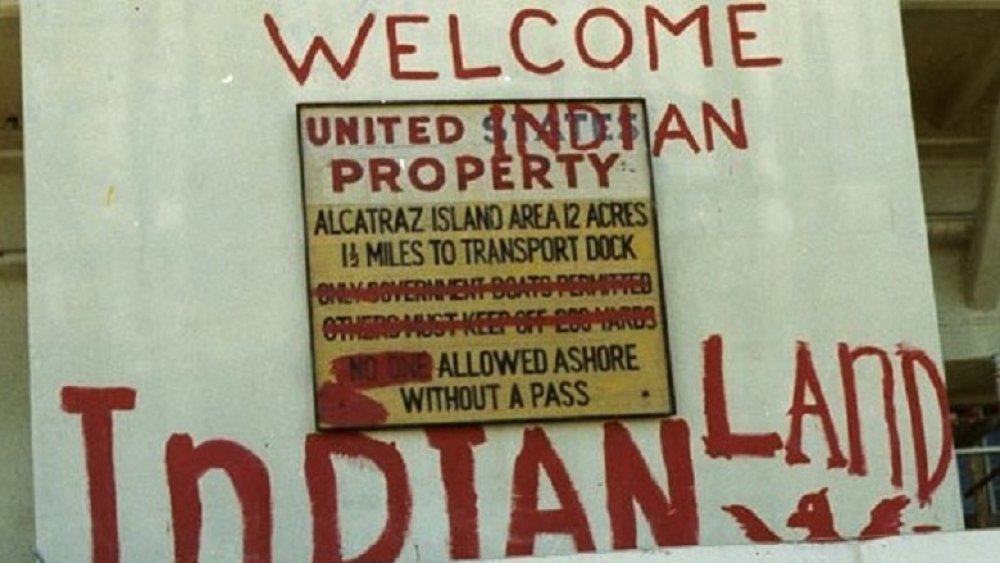

The Trail of Broken Treaties came out of a series of occupations and demonstrations by the American Indian Movement (AIM), a Native American group trying to raise awareness of Native oppression that modeled itself partly after the Black Power movement of the 60s and 70s. Although according to AIM, the group started as a way to try to preserve Native spiritual practices, they quickly became more political, trying to raise awareness of systemic oppression against Native Americans and the massive inequality they experienced in everything from education to health care. As the Encyclopedia of American Indian History notes, after occupying Alcatraz, Mount Rushmore (twice, according to Indian Country Today), and a soon-to-close air base in Minnesota, AIM leaders decided to go cross-country and hit up Washington, D.C. to push for massive change.

From a small protest movement, AIM had become an advocacy group seeking serious social change. And achieving that goal started with demanding representation in the federal agencies that oversaw Native American reservation, determined how much autonomy tribes and reservations had, and otherwise basically controlled Native American life... without admitting that they controlled Native American life.

The Trail of Broken Treaties protested a long history of taking away Native rights

From the earliest colonizing efforts and pushes west by white settlers, Native Americans were mistreated, forced onto reservations, and killed and abused in shocking ways. Even the treaties the federal government enacted were often ignored, changed, or thrown out the window when they were inconvenient for whites. One of the specific acts the Trail of Broken Treaties was calling out was the Indian Appropriations Act of 1871, which gutted every other treaty and totally eliminated Native tribes' self-governance. For over 100 years – from the American Revolution on – the US federal government had treated Native American tribes as independent nations. Sure, their treaties were often made at gunpoint, and nearly always favored the Feds heavily, but at least there was some effort to appear like they weren't just running roughshod over Native groups.

But as the National Archives notes, in 1871, Congress just up and decided, "nope." The federal government didn't want to even pretend to play nice anymore. According to American Indian, the government had had enough of breakaway nations, what with the whole "Civil War" thing, and didn't want to risk any more threats from within. Plus, in a fit of blatant racism, Native groups were considered "wards of the government," unable to take care of themselves. So how could they possibly be sophisticated enough to negotiate a treaty to keep their own land or independence?

The Trail of Broken Treaties commemorated forced marches of Native people

To the leaders of AIM, the Trail of Broken Treaties was a natural reaction to a century of the federal government actively excluding Native Americans from their own governance. They were sick of being marginalized; having lousy healthcare and education available; and being treated like second-class citizens. It was time to act.

And the way they decided to act was no coincidence. The Trail of Broken Treaties, which would start in California and wind 3,000 miles to Washington, D.C., by foot and car, would echo forced marches and relocations of Native Americans throughout history. The Trail of Tears, which the Museum of the Cherokee Indian reminds us forced the Cherokee people and other Southeastern tribes onto reservations in Oklahoma, is probably the best known forced removal. But the National Library of Medicine relates another deadly eviction: the Long Walk of 1864. On that one, the US Army forced thousands of Navajo to march 300 miles to Ft. Sumner; hundreds died on the way. Oh, and when they got there? The survivors were imprisoned with a few hundred Apache — their historical enemies. You can imagine how well that went.

With these brutal memories in mind, AIM organizers set out to write their own history through their march. Instead of being forced to relocate due to persecution and abuse, the Trail of Broken Treaties would involve Native Americans going east to show their power, demanding the restoration of their rights.

The Trail of Broken Treaties gathered steam across the country

When it left the West Coast in early autumn 1972, the protest caravan was relatively small. As detailed in the Encyclopedia of American Indian History, three different groups, each with a few people spread across no more than five cars each, took a different route towards a planned rendezvous in Minneapolis.

As the original protestors crossed the country, visiting more than 33 reservations, more and more folks joined up. By the time they all met up in Minneapolis on October 23, 1972, more than 600 people were ready to really make some serious social change. Since the American Indian Movement had gotten its start in Minneapolis, that had seemed like a good place to stop for a bit and regroup. Part of that plan involved a four-day series of workshops in St. Paul led by Reuben Snake, Hank Adams, and other leaders. In those sessions, protestors met and debated to figure out what exact demands the group would make when they got to Washington. As historian Jason Heppler writes, the protest wasn't just about visibility anymore: it was about creating real policies that would have lasting benefits for tribes across North America.

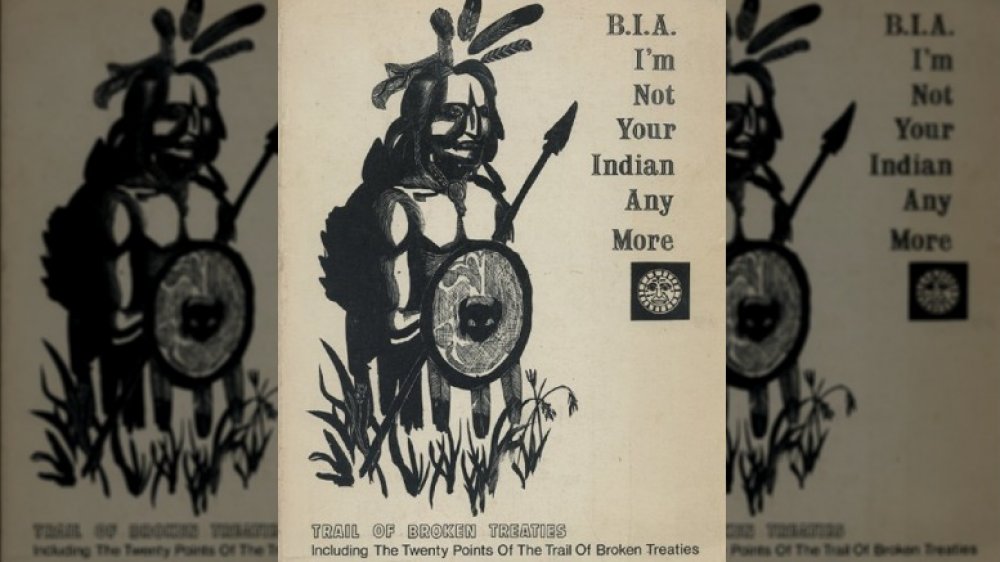

Protesters had a 20-point position paper

After gathering opinions through days of workshops, it was time to put everything together. Hank Adams, who had done treaty law work in the Pacific Northwest according to the Encyclopedia of American Indian History, got the oh-so-enviable job of getting locked in a motel room for two days straight to write the AIM manifesto. He churned out the very engagingly titled "20-Point Position Paper" which, funnily enough, listed 20 very specific goals and actions the movement wanted taken by the federal government. Most dealt with getting actual Native representatives, chosen by actual Natives, in the agencies that were making decisions about their funding and fate. There would be various treaties made or reaffirmed, addresses to Congress and the nation, land reform, and a bunch of other high-level government policy changes.

But the last few points were in some ways the most important to the AIM leaders. Those dealt with community reconstruction, education, religious freedom, and health and human services. Basically, the 20-Point Position Paper led with the incredibly boring legislative stuff and buried their most passionate demands: they wanted social justice and they wanted it now.

With their action plan and demands hammered out, it was time to hit the road again. Archives West writes that protestors planned to present their demands to that year's presidential candidates, Richard Nixon and George McGovern, making use of the media circus that surrounds elections to get some attention for their cause.

Not all Native leaders agreed with the Trail of Broken Treaties

But not everyone was on board with the protest and its plans. Intercontinental Cry points out that many tribal leaders thought the Trail of Broken Treaties protestors were too radical and militant. In their eyes, the 20-Point Position Paper went way too far. It was one thing to be unhappy with the status quo and maybe want a few treaties updated here and there, or even enforced at all. To them, it was totally bonkers to agitate for actual social change. They wanted a softer approach to renegotiating, and didn't want to touch the issue of systemic oppression and inequality with a 10-foot pole.

But it was exactly that inequality that had led hundreds of young people from dozens of tribes to join up with the caravan on its way to the Twin Cities. This was an opportunity for oppressed people to have their voices heard, and they weren't going to waste the chance. In her book Lakota Woman, Mary Crow Dog quoted an Ojibway medicine man, Eddie Benton, as saying the protest united "brothers and sisters from all over this continent united in a single cause. That is the greatest significance to Indian people."

Government officials refused to meet with protesters at first

Of course, what matters to a righteously angry group of protesters who've crossed the country to have their voices heard doesn't necessarily matter to a bunch of politicians. And the AIM protesters learned that firsthand when they made it to Washington in November 1972. With a presidential election coming up, the protesters had figured their timing would be perfect to get incumbent Richard Nixon and challenger George McGovern to pay attention.

Unfortunately, that plan backfired a bit—initially, neither politician was willing to take time away from campaigning to meet with a motley group of a thousand or so protesters fresh from a 3,000-mile trek. Framing Red Power reports that neither the media nor the federal government paid much attention to the protesters even after they arrived in Washington. The New York Times and the Washington Post barely covered the entire multi-week protest caravan. Local newspapers were a little more receptive; the Ann Arbor Sun went off on Richard Nixon for hiding behind a "falsified cloak of peace and good will." But by this point, the situation was dire. Stalled out and with their promised housing having evaporated, the protesters were at a loss for what to do next.

In Washington, but with nowhere to go

Back when AIM leaders were planning the Trail of Broken Tears in August 1972, they had covered all their bases. Framing Red Power reports that they briefed all their participants on staying civil, making sure no one burned flags or blocked traffic, and generally making sure the protest was "our finest hour," as a press release by the AIM leaders read.

And yet once in D.C., everything started to fall apart. As Framing Red Power noted, everything from a planned religious ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery to a peaceful demonstration on the lawn of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) got canceled at the last minute by various federal agencies. Worse, the local churches that had promised places for the protesters to stay mysteriously "forgot" that immediately after they arrived in Washington. According to accounts from the time, the only place they had to stay the first night was crawling with rats. The next day, protesters headed for the only place they could think of to get help: the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). Mary Crow Dog recalled that many of the protesters, including families with small kids, set up camp on the BIA lawn while leaders went inside to try to sort out housing and arrange for meetings.

A misunderstanding led to Trail of Broken Treaties protesters occupying a federal building

And that's where bureaucracy went horribly, horribly wrong. While trying to figure out how to get food, housing, and government meetings, the protestors overstayed the 4:30 pm closing time at the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Building security, probably overwhelmed by the little kids playing on the lawn and "old ladies getting comfortable on couches in the foyer," according to Mary Crow Dog, freaked out and decided to kick everyone out.

Big mistake. Protesters turned the tables and kicked the security guards out instead, triggering what ended up being a 6-day peaceful occupation. As one of the AIM leaders, Leonard Peltier, later recalled, they started the "impromptu sit-in" only when the people who were supposed to be helping them decided not to bother. Another account from the time, reported in Indian Country Today, said the entire occupation of the BIA building was a misunderstanding (unlike the purposeful occupation of Alcatraz in 1969, pictured above). One government department didn't bother telling a second department what was going on, and then a third department came in and tried to boot everyone out. In the end, the AIM protesters wound up taking over the building, giving press briefings, and trying to outlast the police snipers that had been stationed on all the surrounding buildings.

Trail of Broken Treaties leaders eventually got a government meeting

Things weren't exactly organized inside the BIA during the occupation. Despite all the original organizers' careful planning and instructions, the whole protest had gone off the rails on November 2, 1972. They weren't getting their government meetings, their housing had vanished, and they had somehow taken over a federal building.

Inside, folks were starting to split into factions. According to Suzan Shown Harjo, who was on the scene and helping produce media reports inside, the senior leaders were still urging restraint. But younger protesters started suggesting making firebombs, rigging weapons in case SWAT teams were sent in, and more. In the end, the building got totally ransacked – Leonard Peltier recalls desks getting hacked up with axes, while Mary Crow Dog remembers barricading herself in a room, ready to fight off "the pigs" when they came.

Eventually, though, the Secretary of the Interior Rogers Morton turned up, promised to appoint a couple of high-level officials to look into the 20-Point Paper and, you know, pay a little attention to the thousand people who had come to D.C. to peacefully advocate for upholding promises that the government had made to them for a couple hundred years.

Trail of Broken Treaties protesters were promised change

That went about as well as you can imagine. The protestors weren't meeting with President Nixon; they weren't even getting a meeting with Interior Secretary Morton himself. Instead, they'd get a couple of deputies somewhere and maybe a little airtime on local TV. Protesters were unsure whether they'd even get to officially discuss their grievances and the 20-Point Position Paper. Mostly, AIM leaders were sure they would get some nasty FBI and CIA files created on them (and yes, they did).

When they finally got a meeting with the feds, as Indian Country Today notes, the 20 policy and social justice points they were there to discuss were basically ignored. Instead, as the International Leonard Peltier Defense Committee states, the meeting got them a travel budget to get home, immunity from prosecution for taking over a government building (though they were still officially classified as "extremists"), and promises that their policy demands would be considered... eventually.

Although the protestors got their meeting, they didn't get action on most of the points in their position paper. A joint Congressional commission to overhaul the Bureau of Indian Affairs and make some of the demanded changes was eventually set up, according to Intercontinental Cry. Oh, and the Law Library at Jrank.org notes that an actual Native representative was put on the Bureau of Indian Affairs board. But that was about it.

Native Americans are still seeking change today

After a 3,000-mile trek, accidentally occupying a federal building, a few national news interviews, and meeting with a deputy secretary of the interior, the 1,000 protesters who took part in the Trail of Broken Treaties didn't have much to show. Basically, according to Free Leonard Peltier, they got $66,000 to get home and wouldn't be charged over that whole "armed standoff" thing. Oh, and they carted off dozens of boxes of BIA documents, which the Ann Arbor Sun said exposed a history of illegal, oppressive acts by both the government and corporations against Native peoples.

Still, not a whole lot changed after the protest. Today, Native Americans are still trying to make many of the changes the AIM was seeking back in 1972. As Global Citizen reports, even during the COVID-19 pandemic, a huge percentage of people on Native reservations still don't have access to clean water or sewage systems and are cut off from federal resources – Point 20 on the original position paper. Education lags behind federal standards, health and human services resources don't exist, and there's a patchwork of inconsistent legislation and policy governing the whole shebang. However, as Vox points out, a July 2020 ruling by the US Supreme Court paves the way for many of the points in the AIM manifesto to finally be addressed: things like judicial treatment and land reform. Buckle up, gang: the Trail of Broken Treaties might finally be getting underway for real.