What The Last 12 Months Of JFK's Life Were Like

John F. Kennedy was the youngest person to be elected president of the United States and was one of four U.S. presidents to have been assassinated while in office. From the moment President Kennedy was inaugurated, his time in office was defined by one incident after another, from the Bay of Pigs to the Civil Rights marches, culminating in his assassination. Ever since then, many have wondered what the world would've looked like had President Kennedy lived.

Kennedy's final year in office is often overshadowed by his assassination, but his work as president, his successes and his failures, continued until his final days. And although not all of Kennedy's goals would be achieved during his life, some were taken up after his death as others sought to implement the change Kennedy would never live to see. John F. Kennedy became a timeless figure, with countless schools, roads, and parks named after him worldwide. This is what the last 12 months of JFK's life were like.

JFK's crisis resolution and executive order

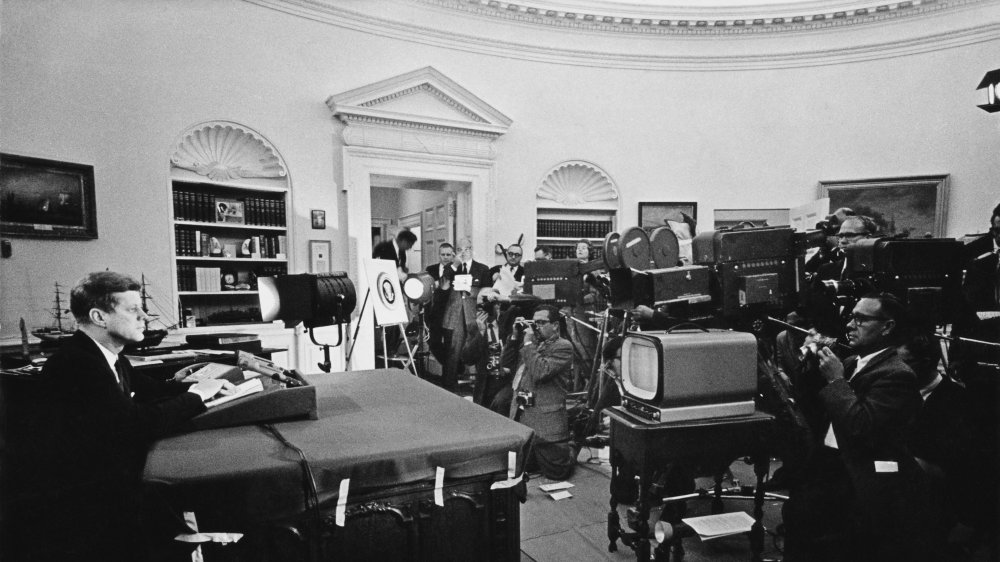

While the Cuban Missile Crisis is considered to have lasted 13 days, tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union continued until late November 1962. On November 20, 1962, after confirming that all IL-28 bomber planes were being removed by the Soviet Union, President Kennedy confirmed in a press conference that he was lifting the naval blockade around Cuba.

During this press conference, JFK also announced the signing of Executive Order 11063. This order attempted to address the segregation and systematic racism that was pervasive in federally funded housing organizations. According to A History of Racial Justice, government-backed organizations like the Federal Housing Administration would frequently determine the riskiness of a mortgage based on the borrower's neighborhood, focusing on its racial demographics. People from "black neighborhoods" would get a worse rating, and as a result, loans were channeled into "white neighborhoods" that were deemed to be "less risky."

Despite the good intentions of the executive order, it had a limited impact. The order only applied to low-income units built after November 20, 1962, and therefore applied to less than one percent of the housing units in the country. The order also advocated self-policing, and with no method of enforcement, there was no threat of federal intervention. As a result, discriminatory lending practices continued until the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

A bomb for a bomb

After the British cancelled their Blue Streak missile program for being too expensive, they replaced it with an agreement to purchase Skybolt missiles from the United States of America. But in December 1962, U.S. secretary of defense Robert McNamara decided to cancel the development of the Skybolt missiles, effectively leaving the British without a nuclear arms strategy.

After discussions dissolved between McNamara and British defense minister Peter Thorneycroft, the British press began harshly criticizing the two administrations. According to The Harvard Crimson, many people in Britain believed that Kennedy had purposefully cancelled Skybolt in order to limit Britain's nuclear potential. As a result, an emergency meeting was set up between Prime Minister Harold Macmillan and President Kennedy in Nassau, Bahamas. While Prime Minister Macmillan was able to negotiate a deal with Kennedy in which Britain acquired submarine-launched Polaris missiles, saving the British government over $800 million in research and development, many saw him to be coming back empty-handed.

President Kennedy also convinced Prime Minister Macmillan to form a multilateral NATO nuclear force, and according to the BBC, many feared that this would result in Britain's nuclear reliance on the United States. President Kennedy also offered to sell Polaris missiles to France's president Charles de Gaulle, though de Gaulle refused and would later use Britain's acceptance of the missiles as reason for vetoing Britain's application to join the European Economic Community in 1963 and 1967.

JFK proposed lowering income and corporate taxes

In January 1963, President Kennedy gave his third, and what would inevitably be his last, State of the Union Address. During this speech, he stated that the "obsolete tax system exerts too heavy a drag on private purchasing power, profits, and employment. Designed to check inflation in earlier years, it now checks growth instead. It discourages extra effort and risk. It distorts the use of resources. It invites recurrent recessions, depresses our federal revenues, and causes chronic budget deficits."

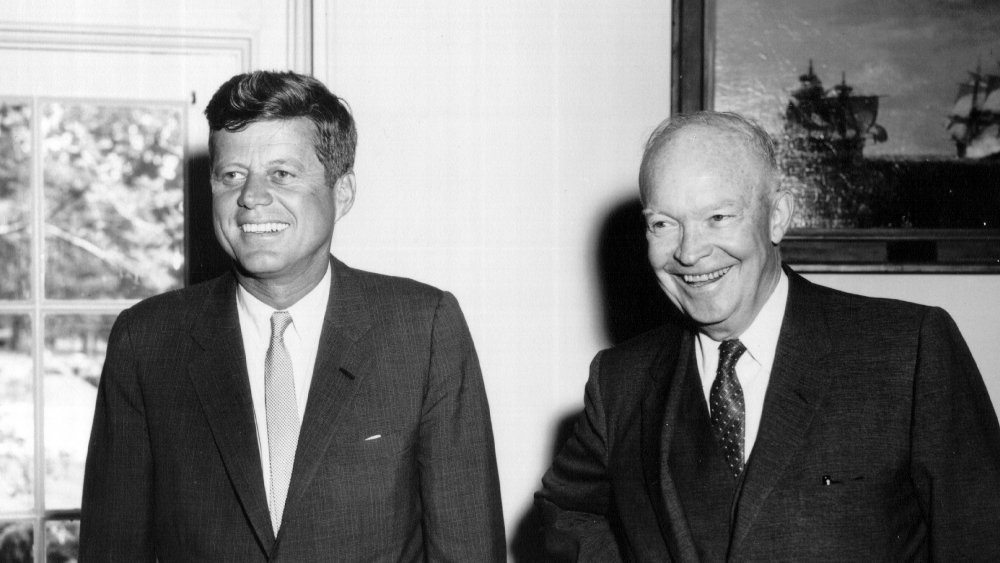

President Kennedy went on to propose a $13.5 billion tax cut, $11 billion of which would result from changing individual tax rates from a range of 20-90 percent to a range of 14-65 percent. The rest would come out of reducing the corporate tax rate from 52 to 47 percent, cutting tax rates that had been set during Eisenhower's administration. According to NPR, JFK had consistently advocated cutting taxes across the board, but many, Democrats and Republicans, worried that to reduce taxes without simultaneously cutting spending would lead to budget deficits. Against this, President Kennedy countered that "a rising tide lifts all boats," a phrase still commonly quoted by Republicans.

In the end, Kennedy's tax cut proposal would be repeatedly blocked in Congress during his lifetime, only to have a version enacted by his successor, President Johnson.

JFK furthers the embargo against Cuba

Even before the Cuban Missile Crisis, the United States had already established "a total embargo upon all trade between the United States and Cuba," continuing to add additional restrictions throughout 1962. However, President Kennedy notably managed to acquire over 1,000 Cuban cigars right before the trade embargo went into effect.

On February 8, 1963, JFK and his administration proceeded to make travel to Cuba by U.S. citizens illegal. Financial and commercial transactions with Cuba would also be made illegal for U.S. citizens as the United States sought to sever any worldly ties Cuba might have had. At the time, the CIA was also in the midst of Operation Mongoose, a covert operation designed to remove Fidel Castro from power. According to Politico, the CIA even recruited two Mafia mobsters to kill Castro, though their efforts would ultimately fail time and time again.

Domestically, President Kennedy made a weak attempt to secure the voting rights of Black Americans. On February 28, 1963, he sent a "Special Message on Civil Rights" to Congress that outlined a series of legislative proposals to be addressed. However, many civil rights advocates criticized Kennedy for the weak proposals in his legislation, and after he did little to promote it, the bill expired without passage.

Courting foreign relations

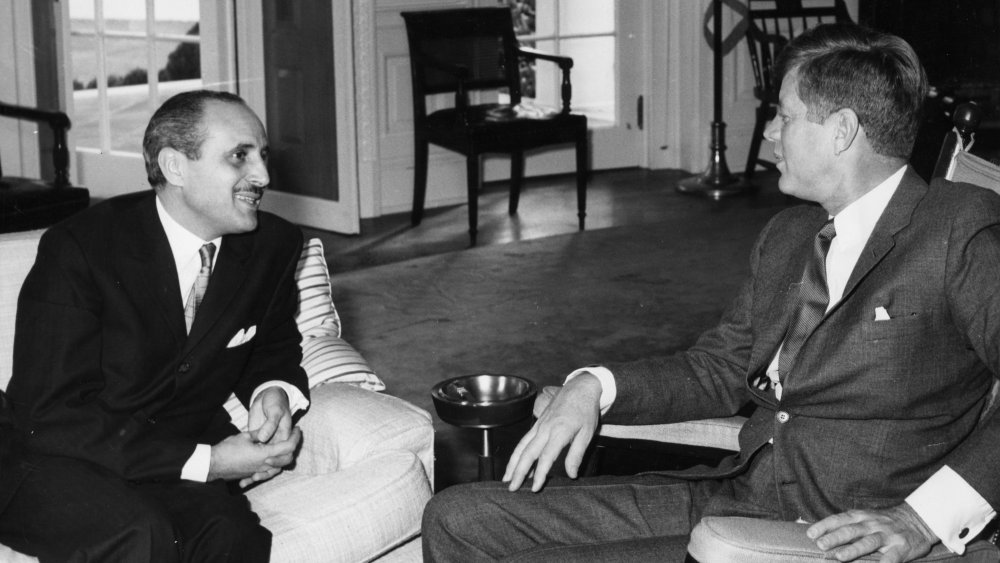

In March 1963, President Kennedy met with King Hassan II of Morocco. According to a memorandum from Acting Secretary of State George W. Ball, JFK was encouraged to have this meeting due to the United States' "military interests and the strategic importance of Morocco's geographic position." The meeting was considered integral toward not only establishing a foothold in Morocco in order to counter the efforts of the Soviet Union but toward showing Algerians that the United States was invested in North Africa.

During this time, President Kennedy also attended the Conference of Presidents of the Central American Republics in San Jose, Costa Rica, making him one of the first U.S. presidents to visit Costa Rica. During this conference, Kennedy hoped to continue the efforts of the Alliance for Progress, which worked to combat the influence of socialism in Latin America.

It was also in this month that Lee Harvey Oswald purchased the rifle with which he would assassinate President Kennedy in November.

JFK looks toward the future and the past

President Kennedy had attended the groundbreaking ceremony for the World's Fair in December 1962, and on April 22, 1963, he activated the clock that was to count down to the New York World's Fair of 1964. Using the first touch-tone push-button telephone, President Kennedy dialed 1-9-6-4 to commemorate the launch of the endeavor.

President Kennedy had christened the theme of the 1964 World's Fair to be "Peace Through Understanding," hoping to exhibit the accomplishments of "a system of freedom." Tragically, JFK wouldn't live to see the end of the countdown, though his wife Jackie Kennedy would visit some of the exhibits of the 1964 World's Fair.

According to the International Churchill Society, on April 9, 1963, President Kennedy also conferred upon Sir Winston Churchill honorary U.S. citizenship. President Kennedy was a lifelong fan of Churchill, reading the latter's work through his youth and frequently quoting Churchill during his 1960 presidential campaign, and it was with President Kennedy's urging that Congress passed legislation that made Churchill an honorary citizen. Due to his health, Churchill was unable to attend the ceremony and was represented his son and grandson, Randolph and Winston.

JFK is confronted by civil rights

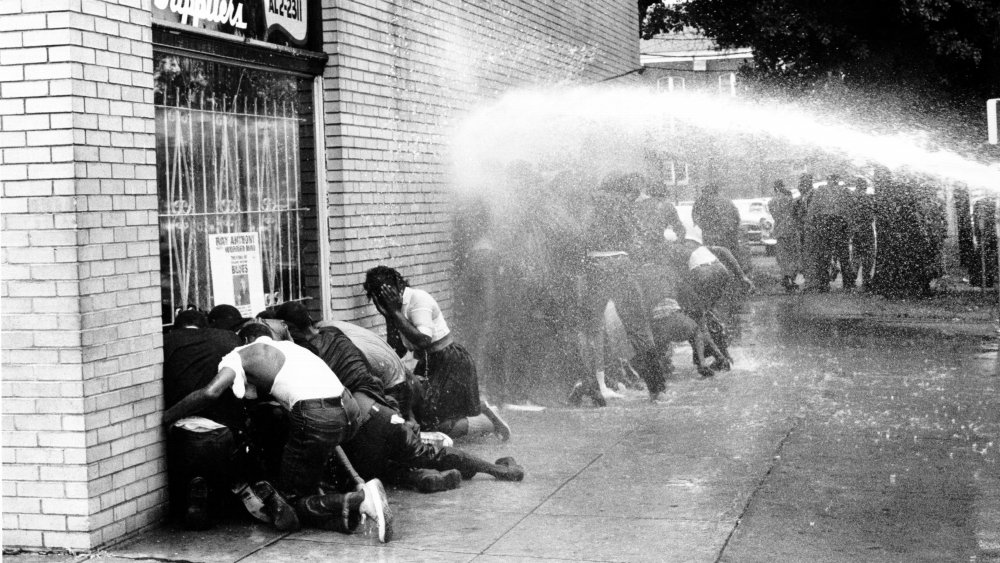

The fight for civil rights in the United States had been going on in Birmingham, Alabama, for several months, but in May 1963, the country watched as peaceful protesters faced off against police with fire hoses and dogs, images televised and reprinted in newspapers and magazines.

According to PBS, throughout most of his presidency, JFK's attitude toward civil rights was seen as noncommittal by many civil rights advocates and leaders. Rather than pushing for large systemic changes, President Kennedy took on a more case-by-case approach. One example is when he made a deal with segregationist governor Ross Barnett to allow the registration of James Meredith at the historically segregated University of Mississippi at Oxford. Kennedy also announced Meredith's successful registration while federal marshals were still battling against violent segregationists.

But the images from May 3, 1963, were unavoidable. According to The Atlantic, the image of a German Shepherd lunging at a young Black boy affected President Kennedy, and he's reported to have stated that the picture "made him sick." Neither President Kennedy nor the United States public could continue to ignore the brutality and oppression that was pervasive in American society. However, it would take another month before Kennedy addressed the nation directly on the issue of civil rights.

A month of historic words

As the National Guard tried to enforce the desegregation of the University of Alabama, President Kennedy addressed the nation on June 11, 1963. In addition to promising to ask Congress for legislation to end segregation in public facilities, he presented civil rights to the public as a moral issue. According to ABC News, JFK's consideration of civil rights as a moral issue came largely from the urging of his brother Robert F. Kennedy, whose thoughts on civil rights had been greatly expanded after a meeting with novelist James Baldwin.

In his civil rights address, President Kennedy urged the U.S. public to recognize that the most important domestic issue at the time was the fight for civil rights. On June 19, he sent a letter to Congress that underlined the importance of civil rights when it comes to the moral standing of the United States. According to The Center for Legislative Archives, this emphasis was most likely made with the Cold War in mind, since the U.S. had recently started sending troops into Vietnam.

President Kennedy also traveled to Europe, where he made his famous anti-communist "Ich bin ein Berliner" speech in West Berlin on June 26. Having traveled to Europe in an attempt to convince European leaders that an Atlantic alliance was necessary, Kennedy's speech in West Berlin was meant to especially underline the United States' support for West Berlin against the Soviet Union.

JFK's close encounter

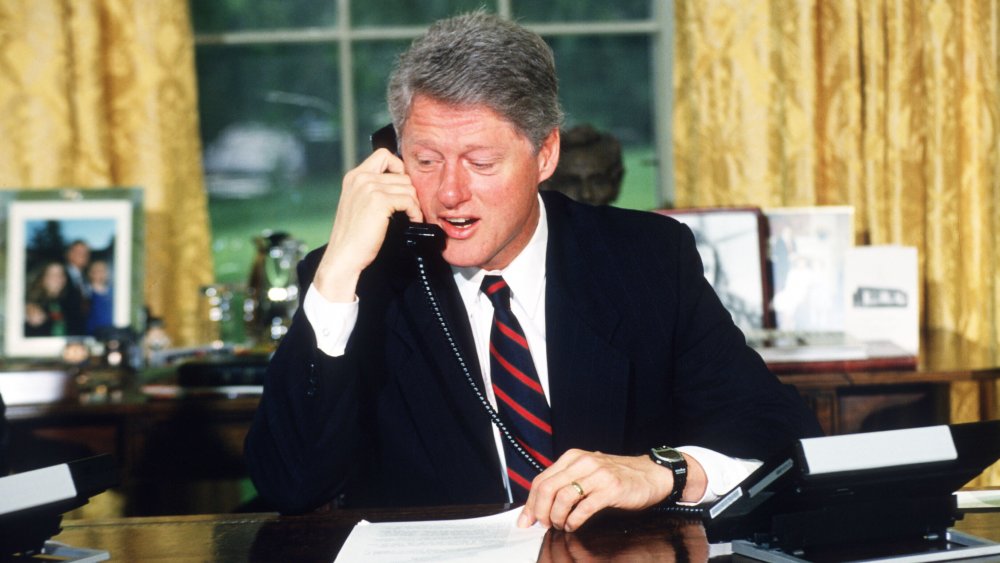

A few weeks after President Kennedy returned from Europe, he met with several delegates from Boys Nation, a program that brought students from around the country to Washington D.C. for seminars and meetings with government leaders and elected officials. The students held mock Senate sessions and were able to sponsor various mock legislations to be voted upon by the group.

When JFK met with the students in the White House's Rose Garden on July 24, he commended them for a civil rights resolution that they had passed in their mock Senate. According to Biography, President Kennedy even compared them with the National Governors Association, who, earlier that week, had been unable to come to a consensus on a similar issue.

As President Kennedy shook hands with some of the boys, a photographer snapped a picture of a young man enraptured by the prospect of meeting the president. After meeting JFK, the young man told everyone within earshot that he would be president one day, and almost 30 years later, that young man, Bill Clinton, was elected to be the 42nd president of the United States.

Instigation of a coup leads to infighting

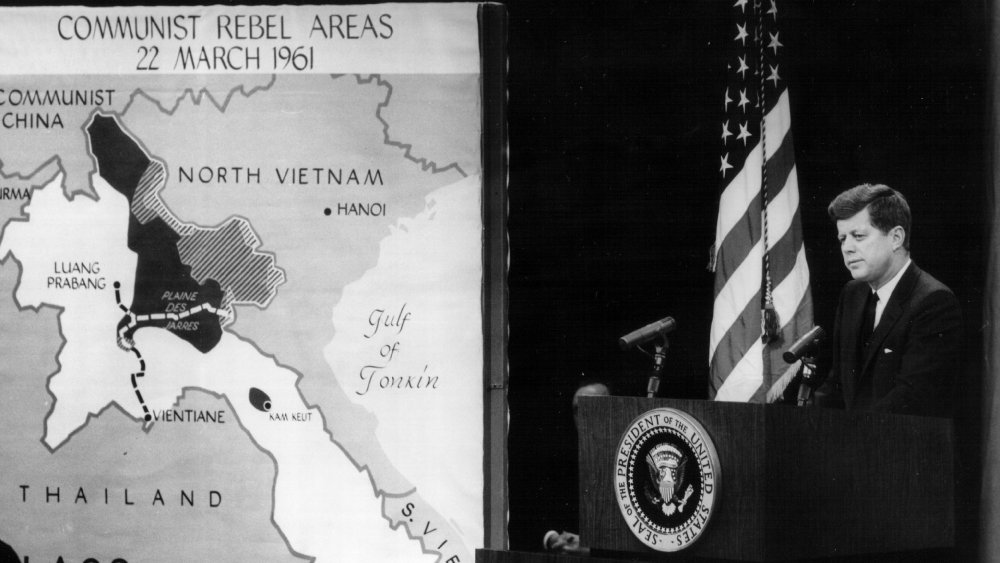

After Vietnam was divided at the 17th parallel in 1954, the United States helped install Ngô Đình Diem as the leader of South Vietnam. Diem was praised as a champion of democracy, despite the fact that during the referendum, Diem won 605,000 votes out of 405,000 registered voters in Saigon. But as Diem began brutally suppressing Buddhists in South Vietnam, the United States worried he was going to alienate the people.

According to the John F. Kennedy Library, Cable 243, which instigated a coup in South Vietnam, can be described as "the single most controversial cable of the Vietnam War." The cable was sent to the U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam, Henry Cabot Lodge, on August 24, 1963, urging him to encourage the South Vietnamese generals to stage a military coup against Diem. National Security Council staff member Michael Forrestal and other second-tier officials had heard whispers of a military coup, and they hoped to encourage it. But when Forrestal called President Kennedy to sign off on the cable, Kennedy told them to ask a senior official first. Forrestal then implied that Kennedy had approved of the cable to get permission from a senior official and returned to JFK with the necessary approval.

Kennedy's national security team was furious, though they were more upset with the run-around than the content, since no one voted to retract the cable. Although the coup would fail, the seeds were sown for Diem's assassination in November.

Revising the draft and revising JFK's image

When the CBS Evening News was expanded from 15 to 30 minutes, it became the first national network's half-hour nightly news broadcast. And for its inaugural episode, Walter Cronkite interviewed President Kennedy outside Brambletyde house on September 2, 1963. During the interview, Kennedy asserted the United States' commitment to anti-communism, describing the country's investment in Vietnam as participation "in the defense of Asia."

Cronkite also asked President Kennedy briefly about the topic of civil rights, through the question focused on how the "civil rights situation" was going to affect Kennedy's chances at becoming the Democratic nominee in 1964. Meanwhile, the "civil rights situation" escalated on September 15, when the KKK bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church, killing four young Black girls and injuring 22 people.

While the country wrestled with domestic terrorism, it began considering its foreign endeavors. According to the Madera Tribune, on September 10, President Kennedy made an exemption for married men aged 19 to 23 from the United States draft, effectively relieving 340,000 young men from military service. Despite the fact that JFK was hoping to minimize U.S. presence abroad, his untimely death led to an administration that preferred the opposite.

The unkept promise of withdrawal

In October 1963, President Kennedy met with various officials in order to implement a plan that would withdraw United States troops from South Vietnam. According to Boston Review, Kennedy was determined to withdraw at least 1,000 troops by the end of the year and to have all the troops out by the end of 1965.

The withdrawal was also not meant to be a noisy affair. According to the "South Vietnam Actions" memorandum from General Maxwell Taylor, U.S. withdrawal was meant to be "low key," without efforts being made toward public relations or Saigon's policies.

Unfortunately, four days after President Kennedy was assassinated, President Johnson approved planning for covert action against North Vietnam and dramatically escalated the war. Crucially, the American public had never been told that JFK had ordered a withdrawal of troops, and Johnson wanted to maintain an air of continuity. As a result, by 1968, the United States had almost 550,000 troops in Vietnam.

JFK's final moments

Two months prior to his death, President Kennedy made a speech at the United Nations General Assembly, inviting the Soviet Union to work with the United States on a joint expedition to the moon. According to Presidential Studies Quarterly, many U.S. officials were alarmed at the notion and saw it as a contradiction of the president's policies. Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev had even been planning on taking JFK up on his offer, and the two were due to meet during a potential visit to the Soviet Union by Kennedy during his upcoming 1964 presidential campaign.

Unfortunately, after President Kennedy was assassinated by Lee Harvey Oswald on November 22, 1963, the Soviet officials were too suspicious of the new Johnson administration to accept a joint mission plan. Kennedy and Khrushchev had developed a rapport over the years, and it was too late to start over with a new president.

The events of JFK's assassination have become a favorite among conspiracy theorists, with many arguing that there may have been a second gunman or CIA involvement, among countless other theories. Since Oswald was shot and killed by Jack Ruby only two days after Kennedy died, the truth of his motive went with him, inspiring generations of theories.