The Messed Up Truth About The Paris Catacombs

There are a lot of famous places in Paris, but the creepiest might just be the catacombs that stretch for miles and miles beneath the city. It's almost difficult to even wrap your head around it: All the time you're visiting cafes, eating pastries, and sipping coffee, looking up at the brilliant Parisian architecture and enjoying the hustle and bustle of the streets, you're walking above the remains of many, many people.

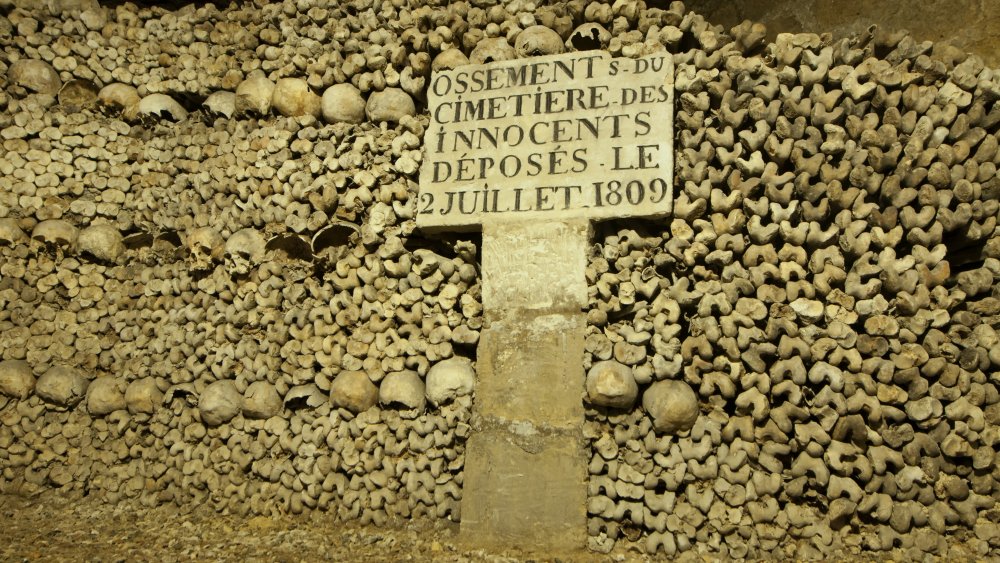

The pictures are stunning: piles of bones and skulls arranged in eerie formations that look like someone with a super-sick sense of humor was trying their hand at creating modern art. There are so many bones that it's difficult to put them into perspective: Each one belonged to a living, breathing human being, with family and loved ones, hopes and dreams, and probably more than a few fears. You know, people not unlike yourself.

The Paris Catacombs are a strange, unsettling place that's worth taking a closer look at ... while remembering that the people buried there probably weren't too different from you.

Why create the Paris Catacombs in the first place?

City planning is a tough thing, and in some cases, cities grew before any planning really happened. That was the case with Paris, and by the 17th century, the Parisians realized they had a huge problem on their hands: the dead.

Les Innocents was the city's oldest cemetery, and it was also one of the biggest. According to Smithsonian Magazine, the neighborhoods around this cemetery were the first to raise some major complaints: The smell of decomposing bodies was so strong that even local perfumers couldn't do business. It was unspeakably bad — the curator of the Catacombs, Sylvie Robin, described it like this (via The Journal): "It was said that the wine was turning bad and the milk was curdling."

In 1763, Louis XV outlawed burials within the city, but there was still the question of what to do with all the people who had already been buried there. A particularly wet spring in 1780 caused retaining walls to collapse around Les Innocents, and suddenly, the bodies that everyone was smelling were spilling into the surrounding properties. The solution? Turn the maze of tunnels beneath Paris — mostly former quarries — into burial chambers.

There are more bones in the Paris Catacombs than you might think

It's almost impossible to appreciate the scale of the Paris Catacombs, in part because most of the pictures you see only show a very small part of what's there. The bones — which, Mental Floss says, occupy a space beneath the sewers and the metro, about 65 feet underground — are the remains of somewhere between six and seven million people. To put that in perspective, that's about the same as the entire population of Massachusetts (via Statistia).

If it doesn't look like there are that many people there from the photos alone, that's because what you're seeing is a facade made of bones. The walls of the tunnels are much farther back than they look, and the spaces between the walls and the facades are filled floor-to-ceiling with more bones ... as you can sort of see in the above photo. And it took workers a good long time to move all those bones: 12 years, says Smithsonian Magazine.

And here's one more fun fact for you: They're not all the remains of Renaissance-era Parisians, either. Some of the bones are around 1,200 years old. That puts them back into the Merovingian era. France's Musee D'Archaeologie Nationale says that people during these times were often still buried with their weapons.

Paris nearly collapsed into the Catacombs

Sometimes, things just happen at the right time. At the same time Paris was starting to wonder what they were going to do with all these bodies of all these people who just kept dying, they actually had another problem on their hands — and the two solutions came together in a way that was very fortuitous.

On December 17, 1774, a mile-long hole suddenly opened along Rue d'Enfer, and in case you're wondering whether or not it was a sign, consider that the translation of that street's name is, according to Odyssey Traveller, the Street of Hell. Fitting, right? Entire houses were swallowed by the earth, and that's about when they knew there was a problem. The 84-foot-deep trench was quickly determined to be the remains of an ancient quarry, and it was shored up and rebuilt. The street above was reopened, but the quarry snaked its way under a huge part of the city, because planning? Bah, who needs it?

When Paris was young and, well, dumb, builders constructed the city from limestone quarried from deep underground. Paris got bigger than anyone expected and spread until it was being built above those tunnels — which weren't incredibly stable. In 1776, the Inspectorate General Service of the Quarries was created to try to prevent disasters like the one that had already happened, and part of the solution? Shoring up walls and tunnels and creating the Paris Catacombs.

The Paris Catacombs are full of eerie quotes and carvings

Not all of the tunnels under Paris are filled with bones, and when visitors enter the part that is, they're greeted by a sign that The Washington Post translates as: "Stop. This is the empire of the dead." Eerie, and accurate.

Other visitors have taken more photos of the phrases that are carved into the limestone throughout the tunnels, and they're things that really make you stop and think about what you're looking at ... and the fact that someday, you're just going to be bone and dust, too. Another (via A Wanderer Abroad) translates to: "Wherever you go, death follows, [as] a body's shadow." There are poems, too, like this one: "They were as we are, Dust, the wind's plaything, Fragile as men, Feeble as the void." And how about this little bit of food for thought? "Where is death? Always future or past. No sooner is she present than she is no more."

Every so often, an eagle-eyed visitor might catch some other carvings, like the initials of an 18th-century stonemason carved into the walls. But there's worse to be seen there, too, as some of the bones have been chiseled, etched, and covered in graffiti by visitors who seem to forget that the bones belonged to living, breathing, feeling human beings.

You'll never guess who turned the Paris Catacombs into a tourist attraction

At first, the development of the Paris Catacombs — nestled deep within the nearly 200 miles of limestone tunnels that twist and turn beneath the city — was a very convenient way to deal with an overwhelming problem. During the first decade-plus of work creating the burial grounds within, it was simply that: a solution.

That all changed when a certain someone marched into Paris and took over. That someone was, of course, Napoleon. By the time France's royalty was unseated, Paris was already changing — it was getting a modern update and overhaul, and Napoleon was a stickler for one idea in particular: that "men are only great through the monuments they leave behind them."

So, he kicked off a campaign of leaving behind monuments and works of art which, says Walks of Italy, is part of what gave rise to the term "Napoleon complex." And here's where the Catacombs come in. When Napoleon looked at the other great cities of Europe and realized that Rome had some seriously impressive catacombs that people could visit, he wanted Paris to have that, too. So, he commissioned Nicolas Frochot and Louis-Etienne Hericart de Thury to turn the Catacombs into a place people would want to go. And they did — they lined the walls with bones in elaborate displays that were built to impress ... and encourage tourists to come.

The bones in the Paris Catacombs still bear hints as to how they died

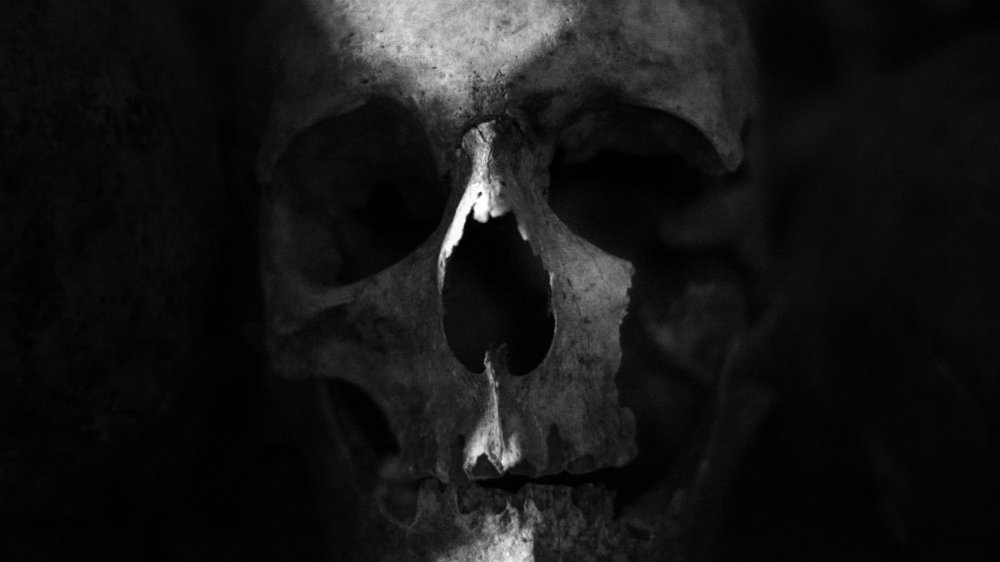

Our bones tell a story, and it's much more detailed than simply how tall we were in life. Bones — like the scores that line the Paris Catacombs — can give clues as to how a person died, and that can provide some valuable insight into what life was like at any given time in history.

National Geographic spoke with a cataphile (someone who loves the underground) named Philippe Charlier, who also happened to be a forensic pathologist at the University of Paris. As an example, he showed them a skull: The lesions on the bone, the larger-than-normal nasal cavity, and the eerie grimace were all signs of leprosy. Lesions on a vertebra? That suggests the person succumbed to Malta fever, and strangely, that fact suggests their occupation. Malta fever was spread through animals, particularly secretions and more specifically through milk. A cheesemaker, maybe?

The wealth of information Charlier can get from the bones is incredible, fragments of lives lived long ago. He can tell if fractures healed properly, what kind of medical treatment a person might have received, accidents they had, and, sometimes, even what foods they ate. Their voices may have been silenced centuries ago, but their bones? They still speak.

Some pretty important remains are ... sort of lost

It's impossible to imagine how daunting a task it must have been, moving some six million sets of human remains. So it's not entirely surprising that we really have no idea who the bones belong to, although On the Luce does say that the catacombs are punctuated with headstones that specify which cemetery they had originally been interred in.

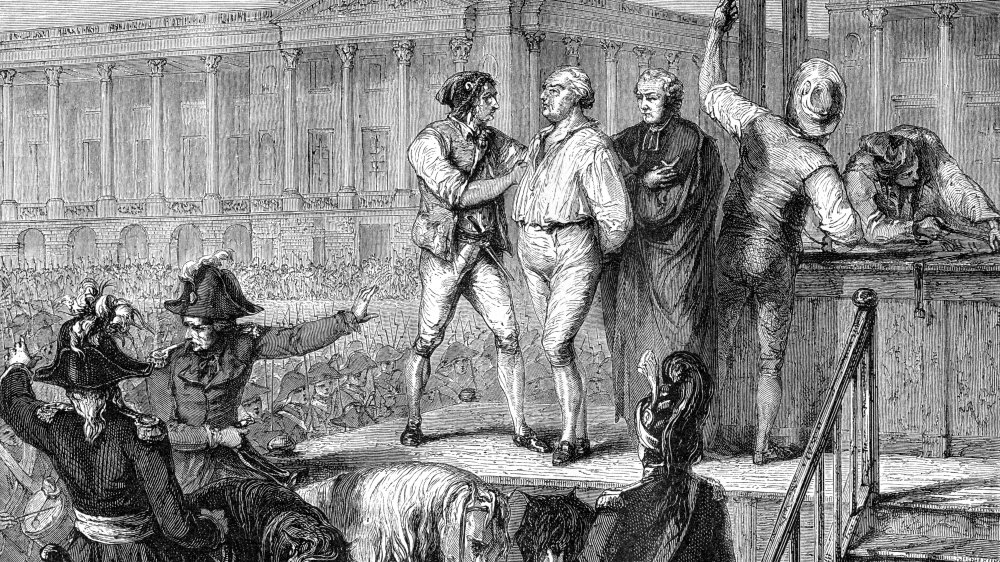

For a long time, the Paris Catacombs were thought to be the final resting place of the men and women who had been guillotined during the French Revolution. According to Verasailles' official website, that's people like Robespierre and Madame Elisabeth, the youngest sister of Louis XVI. Their bones are said to lie side-by-side with the bones of their executioners ... but do they really?

It makes for a great story, but in 2020, archaeologists getting up close and personal with the Chapelle Expiatoire think the truth might be a little different (via The Guardian). The chapel — which is dedicated to Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette — has been found to contain at least four ossuaries within its walls, and it's estimated that the remains of around 500 people might be enclosed within, including the most famous people executed during the French Revolution. Oops!

The heartbreaking sculptures of a doomed quarryman

There are more than just bones in the Paris Catacombs, and if you happen to wander off into a particularly obscure corner of the tunnels, you'll find some incredible works of art with a sad story.

Between 1777 and 1782, a quarryman named François Décure was working deep within the catacombs, and he was carving some incredible things. For five years, while he was on break and on lunch, or before and after his shifts, he retreated into a small side room and carved a group of sculptures that depict places like Menorca's Port-Mahon fortress, where he was held captive during the Seven Years' War. According to Spaces, he also created surprisingly detailed sculptures that are incredibly complex and surprisingly huge — a single cityscape is 40 feet long and positioned precisely along a pool of natural water so that it looks like a port city really is sitting there.

Details, they say, aren't exact – Décure was working from memory, after all, and he hadn't been in some of these places for more than a decade. But that doesn't take away from their sheer scale, complexity, and artistic brilliance at all, and Décure? He wanted people to see them. He was in the process of carving out a staircase that would allow people from street level to easily reach his work when he was crushed in a cave-in. He never recovered, but the sculptures are still there.

Mushrooms grown among the dead

The French might be famous for their cuisine, but some of it is an acquired taste ... like the Paris mushroom. That particular mushroom has a strange history, and according to Atlas Obscura, the tunnels under Paris weren't just used to house the remains of millions of dead — they were also used to grow mushrooms, specifically a type of mushroom that Louis XIV was particularly fond of.

At the time the king was dining on these mushrooms, they were called rose des pres, or pink of the fields. It wasn't until Napoleon came around that farmers discovered that the tunnels underneath Paris were pretty perfect for growing mushrooms ... with one slight addition: the manure produced by the horses of the men who deserted from Napoleon's army and hid in the miles of tunnels.

The climate and permanent darkness meant that the mushrooms could be grown year-round, and they were. By 1880, hundreds of farmers worked underground to produce around 1,000 tons of the mushrooms every year. The tunnels were only abandoned by the mushroom farmers when they started to degrade — and when plans for the metro were put in place. Today, there are only a handful of people producing true Paris mushrooms ... and they're no longer grown alongside the dead.

Is the found footage of the missing man real ... or not?

Found footage is often undeniably creepy. Just look at The Blair Witch Project. Even though you knew there was no way they'd commercialize that kind of footage, there was still a chance it was real ... right? The Paris Catacombs has found footage, too ... and no one's sure what's going on in it.

It's incredibly creepy: It's mostly footage of rooms filled with bones, which means the man filming it is pretty deep inside the tunnels. There are no signs of anyone else with him, and suddenly, he starts to run. His breathing gets more and more labored, and he runs faster and faster, until he drops the camera with a splash. Footsteps can be heard running off into the distance, and ... that's it.

So, is it real? Here's the thing: No one knows. According to The 13th Floor, the footage was reportedly shot sometime in the 1990s and later recovered by a group of people exploring the catacombs. It has been the subject of a documentary and has been shown on TV several times, but it has never been verified as real or debunked. No one has come forward to claim they know anything about the footage, and it is true that there are still huge parts of the catacombs and tunnels that are off-limits to the public. Is there something down there that we shouldn't see?

The lonely death of an 18th-century doorman

Fans of Assassin's Creed might remember a quest in Unity where the player was asked to solve a murder in the Paris Catacombs. The dead man was Philibert Aspairt, and he was found in the catacombs with a Bible, some bottles, a satchel, some beads, keys, and a shovel. Creepy, right? Well, Aspairt was a real person, and the truth is even creepier.

According to Atlas Obscura, Aspairt was working as a hospital doorkeeper during the French Revolution. He went missing in 1793, and for years, that was simply the end of the story ... until his remains were discovered a full 11 years later. In 1804, his body was found in the Catacombs, with no indication of why he might have been down there. Some think he had simply gone exploring and gotten lost, eventually dying there, while others think he was trying to find a way to break into the basement of a local brewery. He was identified by his key ring and the buttons on his jacket, and the place where he died is marked with a gravestone today.

There's a heartbreaking footnote to this: He died just a few feet from a staircase.

The terrible tale of the killer torchbearer

There's at least one tale of murder set in the Paris Catacombs, and it's a doozy.

According to The London Journal, it started in 1824. Alexandre Francornard was a torchbearer working in the Catacombs, and he managed to hook up with a wealthy young widow who was way, way out of his league. Her name was Eugenie Marsac, and she had — in addition to some wealth and a lot of jewels — one young daughter. You can see where this is going.

Francornard eventually offered to show her and her daughter around the Catacombs, and because times were different, she headed down there dressed in all her finery for the day out with her beloved. Francornard returned to the surface — alone — and he had plenty of time to leave Paris before anyone started questioning. Once an investigation kicked off, they found the bodies: Eugenie had been killed by a single blow to the head, and her child had been "dashed [...] against a stone pillar."

Francornard almost got away with it, too, and might have if he hadn't kept a letter she'd written him not long before he killed her. He was on the run for around seven months before he was apprehended, and the punishment fit the crime: He was sent to the guillotine on March 7, 1825.