Messed Up True Stories Of Human Zoos

What images does the term "human zoo" conjure up? It's almost a guarantee that the truth was much worse. Human zoos were exactly that — zoos and exhibitions where humans were on display, oftentimes in their "natural habitats." (It's worth noting right now that there's going to be a lot of words in quotation marks here, because we're going to have to call people things like "specimens" and "savages"... like, a lot.)

According to the BBC, many human zoos were filled with "specimens" (see — just like that) from countries and territories that had been colonized by Europeans. Hundreds of thousands of people — particularly in the late 19th century — visited these zoos, and what went on there was very much like you might expect if it were lions or zebras behind those bars. Visitors would stare and sometimes, says DW, they were allowed to touch the "exhibits": stroking their hair, sniffing them... so yes, it was more terrible than you're imagining at first.

Many people were kidnapped and sold to zoos, while others were told half-truths to get them to volunteer. And many of them died there. Here's more on the horrifying truth of human zoos.

Who's to blame for human zoos? Carl Hagenbeck

Zoos are one of those things that are highly polarizing: there are some who say no animal should be kept on display behind bars, and there are others who think it's perfectly fine if they're cared for — and especially if they're endangered, and keeping them in captivity is going to give the species another chance.

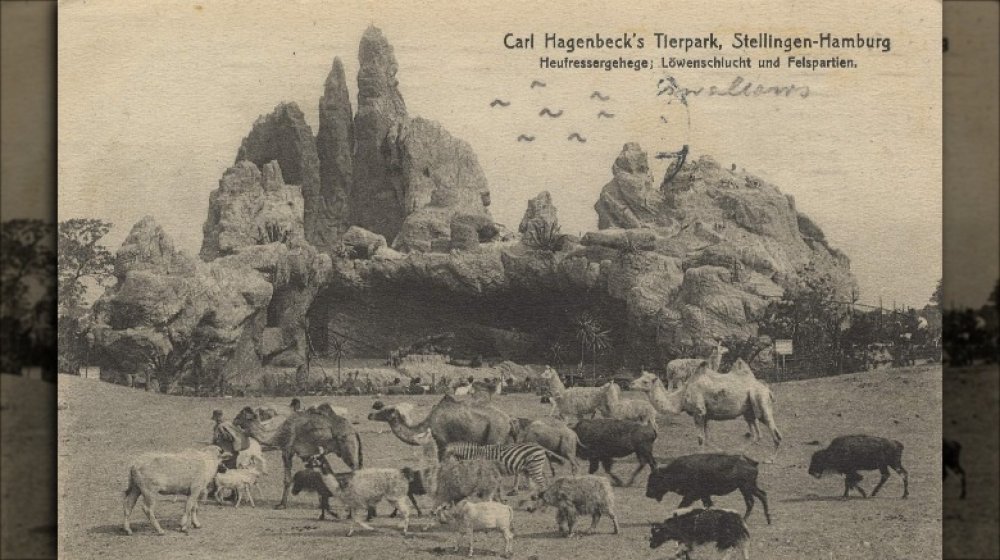

To that end, zoos have come a long way. Visit one now, and you're likely to see animals confined with invisible ditches, surrounded by trees and plants (or rocks and sand, depending on the animal). That kind of natural environment was the brainchild of one man: Carl Hagenbeck. DW calls him the man who invented the modern zoo... but there's a catch to his legacy.

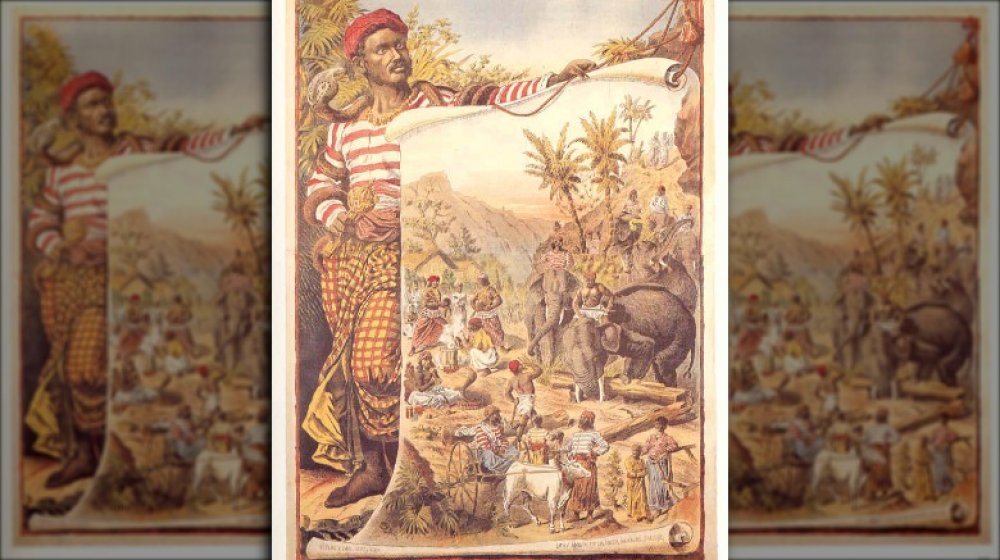

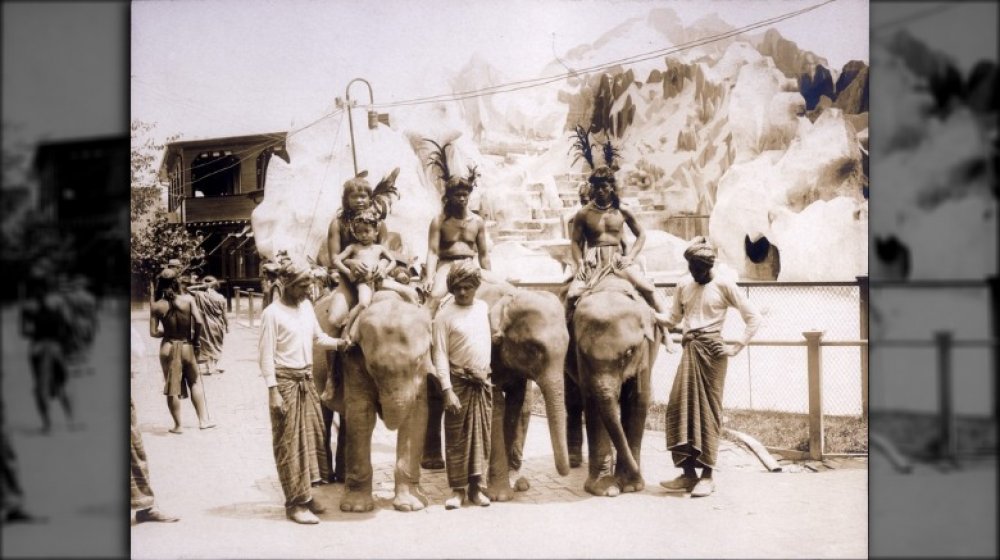

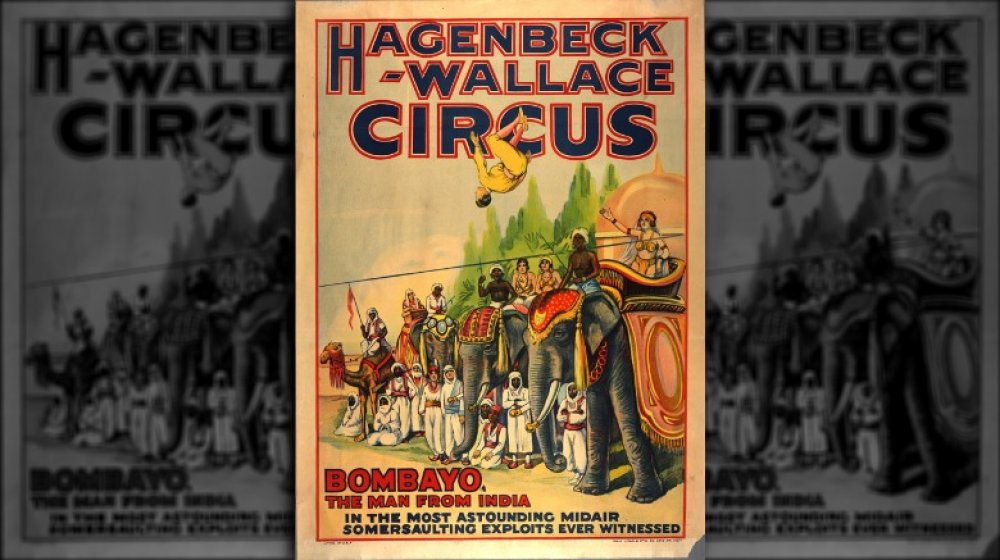

Hagenbeck was a rare and exotic animal trader, and he was also the first to add a human element to his shows, says research from the Universidad Complutense. In 1874, he organized an exhibit that included some reindeer and Sámi peoples (who are the indigenous people of Lapland). It wasn't just about the people: he included some traditional dwellings, tools, and foods, too. From there, it wasn't long before zoo directors realized they could have people stage ritual dances and ceremonies, sing traditional songs, and do day-to-day activities... and other people would come to watch.

But human zoos were built on a very long tradition of displaying other humans

Carl Hagenbeck may have been the first to create zoo exhibits featuring humans, but the idea of displaying people for some large-scale entertainment goes back a long way — to at least the 15th century. That, says Understanding Prejudice, is when Christopher Columbus brought Native Americans back to Europe with him, writing: "They should be good servants [...] I [...] will take hence [...] six natives for Your Highness." Those people were then paraded through the streets of major Spanish cities like Seville and Barcelona.

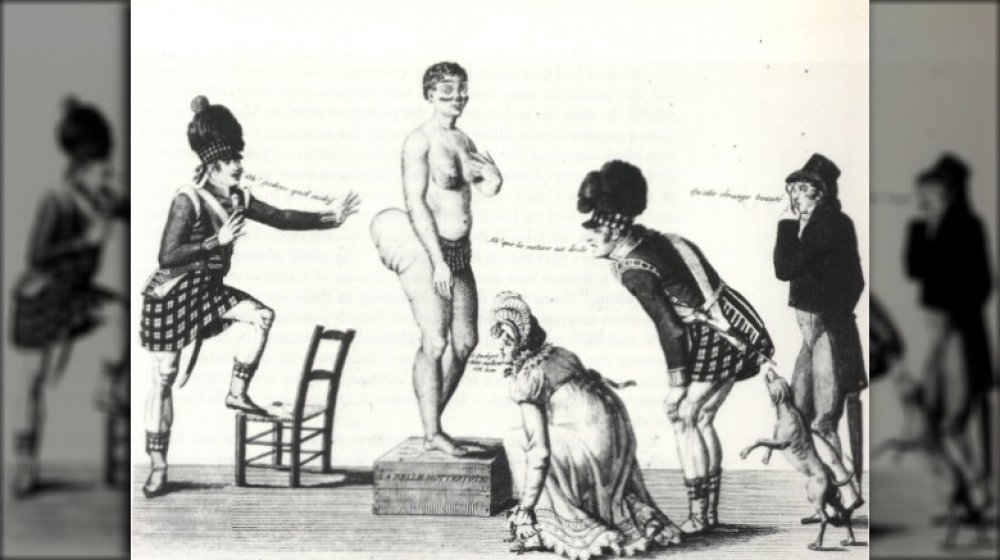

Then, there were people like Sarah Baartman (pictured), who was born in 1789 and exhibited across Europe as the "Hottentot Venus." According to the BBC, she had a medical condition called steatopygia, which resulted in prominent buttocks: she was dressed in skin-tight clothing, visitors were invited to stare, and during private shows, they were even allowed to touch her. She died in 1815, and her skeleton, sex organs, and brain were put on display until 1974.

From there, it was only a short hop, skip, and a jump to full-blown exhibits that CNRS News says included any people deemed "exotic" by the same European cities that prided themselves on their modern thinking. Cities like Brussels, London, and Hamburg exhibited people from Egypt, Korean, and from across Africa. Some exhibits even had signs like the one in an 1897 Brussels exhibit that warned: "Do not feed the Congolese. They have been fed."

P.T. Barnum was in on the act early

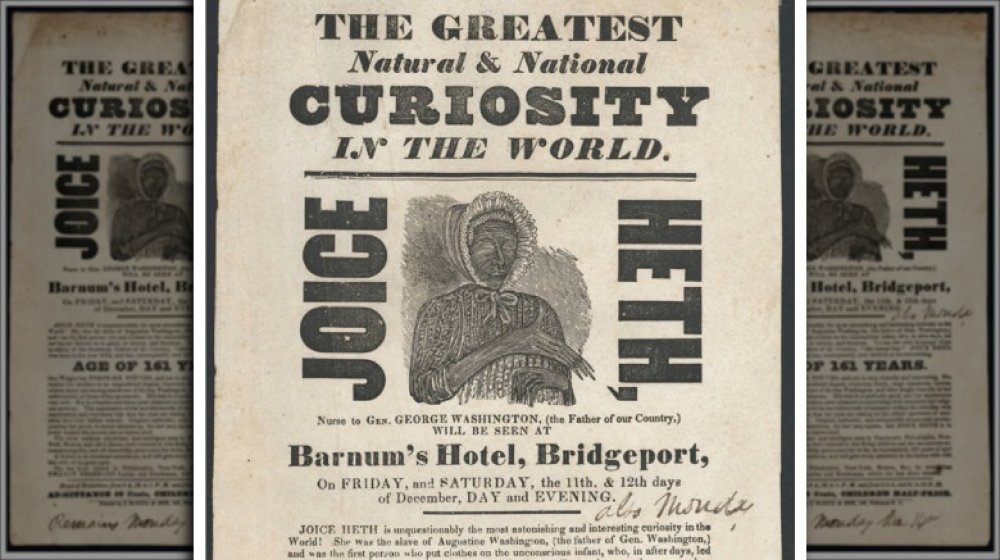

In case your only experience with the history of P.T. Barnum was The Greatest Showman, it's worth mentioning that the real Barnum was a pretty shady sort of character. He got in on the whole idea of exhibiting people pretty early, at the expense of a slave named Joice Heth.

In 1835, Barnum went on tour with Heth, claiming she was the 161-year-old former nursemaid to George Washington. According to The Lost Museum Archive, ticket sales boomed for around seven months, and for that entire time, Heth was on display 12 hours a day, 6 days a week (via Wiley Online). And don't worry, it gets worse. When ticket sales started to decline, Barnum penned an anonymous letter to a Boston paper: Heth was a fake! Not just a fake, it claimed, but she was a machine, cobbled together from whale bones and covered with old leather.

Already think he went too far? He went farther. When Heth died in 1836, Barnum rented Broadway's City Saloon and sold tickets to her autopsy, and the idea was that he was going to prove her age and her story. The fact that New York surgeon Dr. David L. Rogers found (via Online MedEd) that she was only about 75 to 80-years-old and the story wasn't true wasn't a problem for Barnum: he simply claimed the autopsy was done on the wrong body, and the real Heth was alive and well.

Human zoos exhibits looked like home... but definitely weren't

Just like Carl Hagenbeck promoted the idea of exhibiting animals in enclosures similar to their native environments, there was a sad attempt made to do the same in human zoos. For example, says DW, those in the Egyptian enclosure would often share their space with camels, and in the background, there would be cardboard backdrops and papier-mâché pyramids. Just... like... home?

Similarly, members of African tribes would have huts to live in and bones to put in their hair, while Laplanders sat alongside reindeer. Historian Hilke Thode-Arora explained: "Carl Hagenbeck sold visitors an illusion of world travel with his human zoos."

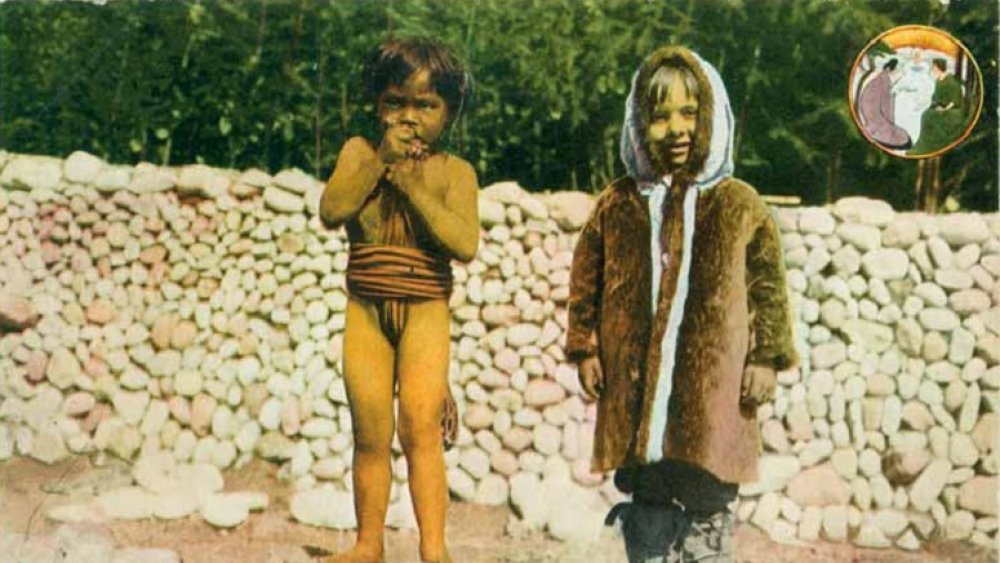

And while there may have been weak attempts at making an exhibit look like home, it definitely wasn't — a fact that became painfully clear when "specimens" began to die. Poor working conditions and the steady flow of visitors meant that people were exposed to a ton of illnesses that they had no natural immunity to. Entire exhibits succumbed to illness: in 1880, an Inuit family — who hadn't been vaccinated against smallpox — contracted the disease and died, while measles, pneumonia, and consumption killed an entire group of Sioux. The trend continued.

Some were on display 'voluntarily'

Where did all of these people come from? It varied — some were plucked right from their homelands and taken halfway across the world. The Guardian, for example, describes Belgium as "importing" 267 people from Congo to be put on display in one of their zoos. Sometimes it was against their will and sometimes they were given a vague idea of what they would be doing — and a promise they'd be allowed to go home (via Rhode Island College). Other times, well...

Let's take the story of Theodor Wonja Michael. His mother was from East Prussia and his father was from Cameroon. At the end of the 19th century, the whole family moved to Berlin. When his father couldn't find a regular job, he turned to doing the only thing he could to support his family: agreeing to be displayed in a human zoo. And there were a lot — DW says Germany alone had about 400 of them.

When Michael's mother died, it was ruled that his father could no longer care for him and his siblings, so they were put into foster care. With whom? The owners of a human zoo officially became their foster parents, and the siblings were split up and included in various exhibits showing "a typical African lifestyle." He went on to write a book about his experiences, saying of his foster parents, "Their only interest in us was for our labor."

The largest human zoo in history was in St. Louis

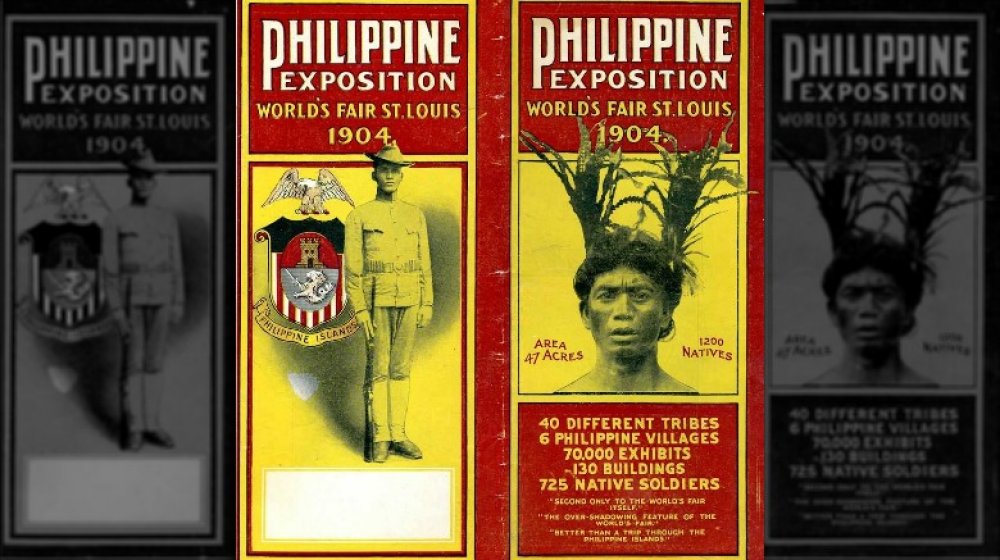

It wasn't just the colonial powers of Europe that delighted in the staging of a good human zoo, and the biggest of them all was at the 1904 World's Fair in St. Louis. Around 10,000 people were brought in to play a part in the zoo, and exhibits included "Patagonians" from the Andes, Ainu from Japan, "pygmies" from Africa, and don't worry, North America was represented, too, with 51 of the First Nations there. Among them? Chief Joseph, the Nez Perce leader who had seen the massacre and starvation of his tribe (via Biography), and the Apache leader, Geronimo. Can't get worse? We'll take that bet and raise you: part of Geronimo's daily routine was posing for photos with visitors and playing the part of Sitting Bull in reenactments of the Battle of Little Bighorn.

One massive section — 47 acres, to be precise — was turned into a "Philippine Reservation," and remember, the US had been involved in a war with the Philippines that had only ended 2 years before. That sort of explains why it was the responsibility of the US War Department (and then-military-governor of the Philippines and future president William H. Taft) to gather around 1,400 Filipinos for the exhibit. The message, says Lapham's Quarterly, was clear: These are the people conquered in the name of white progress.

An estimated 99 of every 100 people who attended the World's Fair visited the "reservation."

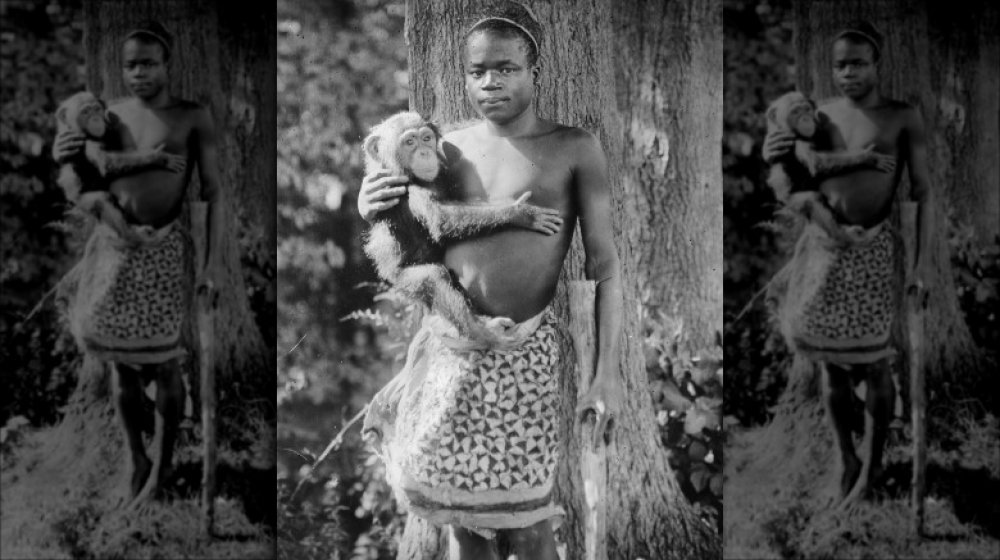

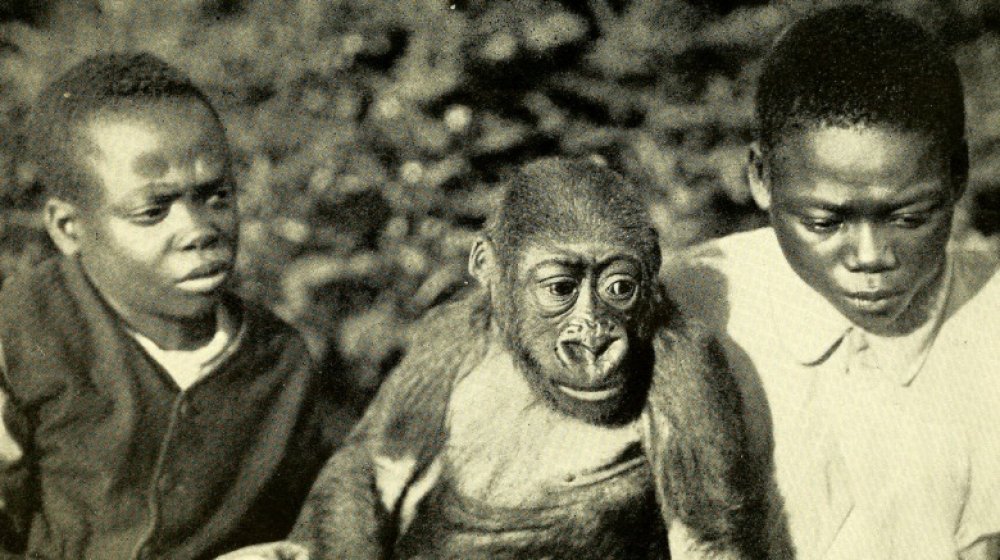

The heartbreaking tale of the Pygmy in the zoo

Ota Benga was born around 1883 in Congo and eventually got married and started a family. But he was still young when everything changed — he returned from hunting to find his village massacred. He was captured and sold into slavery, catching the attention of S.P. Verner, who was in Africa collecting people for the human zoos of the St. Louis World's Fair. He bought Ota Benga — along with seven others — and took them to St. Louis where they were put on exhibition... as, Lapham's Quarterly adds, cannibals.

When Verner started having financial difficulties, the Smithsonian says he made arrangements for his young charge to go live at first the American Museum of Natural History then the Bronx Zoo. For a while, Benga helped out with the animals... until the powers that be hit upon the idea of displaying him in the Monkey House with the chimpanzees. Yes, it was totally controversial, with the Reverend James H. Gordon writing (via The Guardian), "We are frank enough to say we do not like this exhibition [...] We think we are worthy of being considered human beings, with souls."

Still, it continued until a confrontation between Ota Benga and a keeper: then, he went to the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum and eventually moved to Lynchburg, Virginia. There, he made friends, regaled the children with stories, and in 1916, killed himself after sinking into depression.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

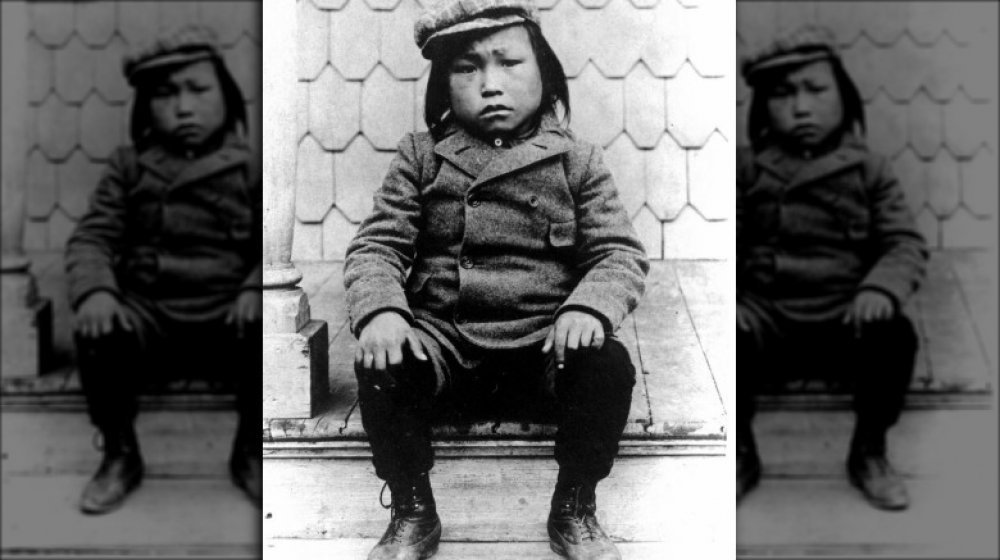

The tragic tale of Minik Wallace

It's unclear how many people were exhibited in human zoos over the decades, but it's the stories of the individuals that are more telling than numbers. Individuals like Minik Wallace. According to Rhode Island College, he, his father, Qisuk, and four others were moved from Northern Greenland to New York's Museum of Natural History in 1897, part of the spoils of an expedition by Robert Peary. They were kept in a basement at least some of the time. One by one, they began to succumb to tuberculosis.

Minik's father was the first one to die, and Minik wanted to perform a traditional funeral. There was a catch: the museum wanted to keep Qisuk's body for study. Not about to let decency and the wishes of an orphaned boy get in the way, they created a fake body, added some rocks to the coffin, and went ahead with the "funeral."

Once Minik was the only surviving member of his little group, he was adopted by museum official William Wallace. At the same time he was raised at Wallace's estate, it also the site of the preparing, defleshing, and mounting of Qisuk's skeleton. Why? So he could be displayed at the museum. Minik did, indeed, discover what happened to his father, and while he returned to Greenland briefly, he resolved to get his father's remains repatriated. He went back to the US in 1916 but died during the flu epidemic of 1918, before he succeeded in his quest.

The science used to rationalize the existence of human zoos

It goes without saying that the entire premise of the human zoo was built on extreme racism, but at the time, there was more to it than that. Sometimes, the exhibits were described as "ethnological expositions," giving them a little bit of science cred. (Ferris State University's Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia points out that they were often called "Negro villages," too, just in case the whole racism thing wasn't 100 percent clear.) Many were organized by people who used them as an opportunity to cement their own ideas about eugenics. Ota Benga, for example, was displayed with a sign — put there by socialite and eugenicist Madison Grant — that identified him as "The Missing Link." See, science!

According to CNRS News, these zoos were a favorite place for a certain type of anthropologist. Namely, these were the ones that were working on theories of biological racism, which basically suggested there were distinct physical differences between races that made some inferior and others superior.

For a while, human zoos were seen as a great place for scientists to take measurements and observe "specimens" of various races, but that sort of fell out of favor by the 1880s... and not because people started to realize there was something terribly wrong about it all. Nope — they were raising "doubts about the representative nature of the people displayed in enclosures."

Us. vs. Them

The late 19th century was a period of extensive colonialism, and the human zoos played a huge role in the public perception on how it was perfectly acceptable for European powers to go stampeding into other countries, planting flags, and declaring that they were in charge.

According to CNRS News, human zoos went a long way to selling the idea that some countries just needed a guiding, European hand, because on their own? "Look at these people. Clearly, they're savages and are much better off as a colony." We're paraphrasing, of course, but that was the idea. It helped white people feel superior, and it made them feel better about the atrocities that were being committed in the name of civilization and advancement.

And this wasn't just something happening in Europe. In the St. Louis World's Fair of 1904, Lapham's Quarterly says slavery was on full display. At a time when Jim Crow laws were in full swing and segregation was still the norm, the only place Black Americans were represented was in a human zoo exhibit called the "Old Plantation." There, actors staged religious revivals, worked in the garden, and sang songs about how wonderful it was to be a slave. Human zoos helped people believe that atrocities and racism weren't so atrocious after all.

Human zoos went on for a shockingly long time

Surely, human zoos were super olde-timey, right? Not quite. The world's last official human zoo was staged at the 1958 World's Fair in Belgium.

At the time, Congo was a Belgian colony, and they saw the fair as an opportunity to show off what The Guardian says they described as "a special bond," by setting up a "typical" Congolese village where men, women, and children went about their "typical" day... while being relentlessly mocked. Often, visitors threw bananas at them. The entire thing, says NPR, was actually an extension of a similar zoo, where King Leopold II kept a few hundred people on display at his country estate in Tervuren.

That horrible bit of history is only overshadowed by Belgium's history in Congo, defined by a king who ordered his soldiers to turn entire villages into slave labor camps. While women were held hostage, the men were forced to go and gather wild rubber. If they didn't gather enough? The soldiers would cut off the hands or feet of the offending slave's children. Special bond, indeed.

The lasting legacy of human zoos

Human zoos have left a strange legacy behind. Take St. Louis. There's a neighborhood there called Dogtown, a nickname that was given because, says Lapham's Quarterly, of the rumor that it was a favorite area for the residents of the Philippine Reservation. Why? It was said that they liked to eat dog, and Dogtown was supposedly where they got the unlucky dogs.

There's another huge problem too: the remains of those who died so very far from home. In 1881, German authorities took 11 Kawésqar from Chile and exhibited them in a human zoo. Five were dead by 1882, and it wasn't until 2010 that their remains were returned to Chile and their ancestral hunting and fishing grounds (via Guelph Mercury).

According to Hyperallergic, the movement to repatriate the remains of indigenous people only started gathering momentum in the 1980s, and it's been shockingly difficult. Even when the remains are in the Smithsonian it can take a long time, partially because they're not sure what they have. It was only when they were sorting through collections around the establishment of the National Museum of the American Indian in 1989 that they realized they had brain fragments from a man named Ishi, who died while on display at the University of California's Museum of Anthropology. He didn't get home until 2000. And remember Minik, the little boy who attended a fake burial for his father? It took until 1993 to have his father's remains returned to Greenland.