The Cuban Missile Crisis Finally Explained

In October 1962, an American spy plane captured images of Soviet-installed nuclear missile sites in Cuba. President John F. Kennedy, with the memory of the failed Bay of Pigs invasion still fresh in the nation's mind, was determined not to let the Soviet Union get away with installing nuclear weapons just 90 miles off the coast of American soil. He immediately convened an executive committee of advisors and demanded that the Soviet Union dismantle the military bases and remove their weapons from Cuba.

The political and military standoff that followed between the United States and the Soviet Union resulted in a naval quarantine, a downed American plane, and the constant fear of nuclear escalation. Confrontations between the two superpowers brought the world almost to the brink of nuclear war. Negotiations finally brought the crisis to an end, but for 13 days, the world was the closest it had ever been to nuclear annihilation.

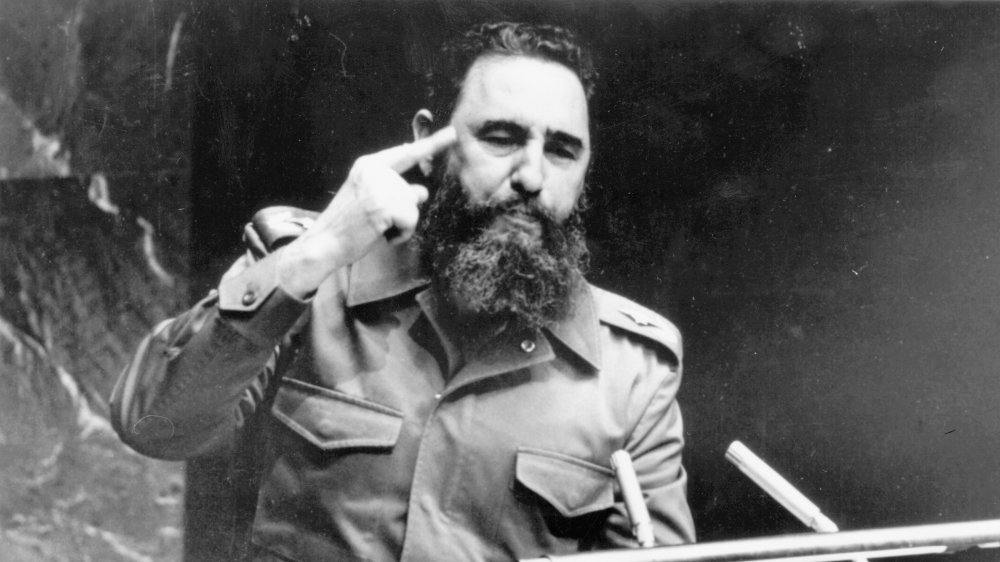

Fidel Castro's rise to power

When President Kennedy entered the White House in 1961, he inherited one of the biggest threats to American safety that had ever existed on the planet: The Cold War. Relations between America and the Soviet Union were tense, and the US had experienced a significant blow at the turn of the decade. At the end of 1959, nationalist revolutionary Fidel Castro had successfully led his guerrilla army in a revolt against General Fulgencio Batista, Cuba's anti-communist, pro-US president. Batista had allowed US companies mostly free reign over their operations and influence in Cuba. However, Castro believed Cubans should have more control over their own interests, and he resented American corporations' heavy involvement in the nation.

When he came to power, Castro immediately nationalized formerly US-controlled industries and began opening up relations with the Soviet Union, per History. By 1960, Castro had officially declared himself a communist and a formal ally of the Soviet Union. Having lost a significant ally with the overthrow of President Batista, the US government under Dwight Eisenhower supported attempts to overthrow Castro. The CIA funded and provided arms to militant, counter-revolutionary groups who were organizing guerrilla movements to overthrow the Castro regime, but they were unsuccessful, according to the CIA.

The failed Bay of Pigs invasion

When he took office, one of Kennedy's first priorities was to oust Fidel Castro. In February 1961, Kennedy authorized a planned invasion that had been conceived under the Eisenhower administration. Using 1,400 American-trained and armed Cuban exiles, the CIA had devised a plan to drop them into a remote area on the southwestern coast of Cuba called the Bay of Pigs, where they would start an uprising and overthrow Castro.

Things went awry almost immediately. The plan's success relied in part on the destruction of Castro's air force, which would prevent him from mobilizing a response to the invasion. The initial plan called for a squadron to conduct two air strikes on Castro's air bases in World War II-era B-26 bombers that had been painted black to look like Cuban planes, per the JFK presidential library. However, the first strike missed its mark, leaving Castro's air force intact and alerting the Cubans to the United States' involvement in the plan. Kennedy cancelled the second air strike, but not the invasion.

On April 17, a brigade of Cuban exiles came ashore at the secluded landing site along the Bay of Pigs. Almost immediately, they were overwhelmed and outnumbered by Castro's forces. With Cuba's air force still up and running, Cuban planes dominated the skies, sinking ships and shooting down back-up planes that were sent to assist the brigade. The invasion was crushed in less than 24 hours. 114 exiles were killed, almost 1,200 were captured, and the failed Bay of Pigs disaster would remain an embarrassing mark on the Kennedy administration.

Operation Anadyr

After the failed Bay of Pigs invasion, the Soviet Union became more determined to support the Castro regime. It greatly benefited them to have another communist government ally, especially one that was located so close to the United States. The Soviets wanted to offer protection if the US attempted another invasion like the Bay of Pigs in the future, but Soviet General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev also saw an opportunity to counter America's lead in nuclear capabilities and even out the disparity between US and Soviet nuclear missiles. At a meeting in April 1962, Khrushchev declared, "Why not throw a hedgehog at Uncle Sam's pants?" by deploying Soviet missiles to Cuba, via the Atomic Heritage Foundation.

Most importantly, Khrushchev saw arming Cuba as an opportunity to gain leverage against the US for having deployed Jupiter missiles in Turkey. In May of 1962, Khrushchev launched Operation Anadyr. Under the guise of promoting a civilian agricultural development program, a delegation of Soviet troops began covertly deploying nuclear weapons to Cuba. Beginning in July of 1962, the Soviets deployed weapons, supplies, and 41,902 Soviet soldiers to the island.

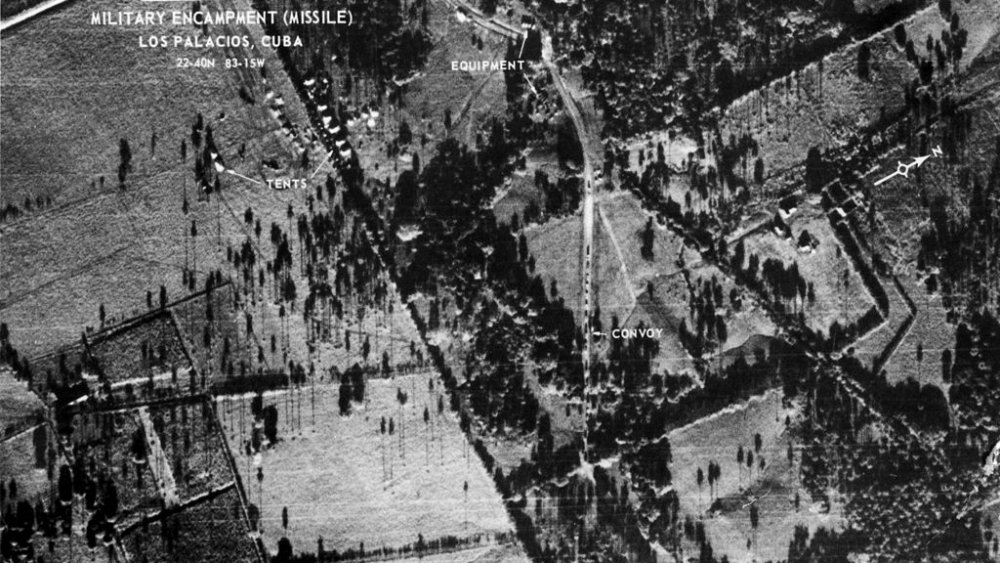

A U-2 spy plane discovers the missile sites

Over the course of the summer of 1962, the Soviets successfully deployed a "motorized rifle division to Cuba, as well as forty MiG-21 jet fighters, two anti-aircraft divisions with SA-2 surface-to-air missiles (SAMs), 16 ballistic missile launchers loaded to fire R-12 and R-14 missiles, six Il-28 jet bombers, and 12 FROG-3 tactical ballistic missile systems," via National Interest. Just 90 miles off the coast of Florida, the nuclear weapons were well within reach of the American mainland.

The Soviet Union's goal was to keep the operation a secret from the United States until it was too late for them to interfere, and they remained undiscovered until October 14th, 1962. Air Force Major Richard Heyser was piloting a U-2 spy plane over Cuba when he captured photographs of the Soviet ballistic missile sites at San Cristobal. The images clearly showed the construction of medium-range and intermediate-range ballistic nuclear missiles sites. Per the Atomic Heritage Foundation, the existence of the nuclear missiles was further confirmed by information that had been collected by a CIA spy named Colonel Oleg Penkovsky. It was official: The Soviets had deployed nuclear missiles within easy reach of the eastern US, ramping up the nuclear arms race and escalating Cold War tensions to dangerously unprecedented levels.

ExComm convenes

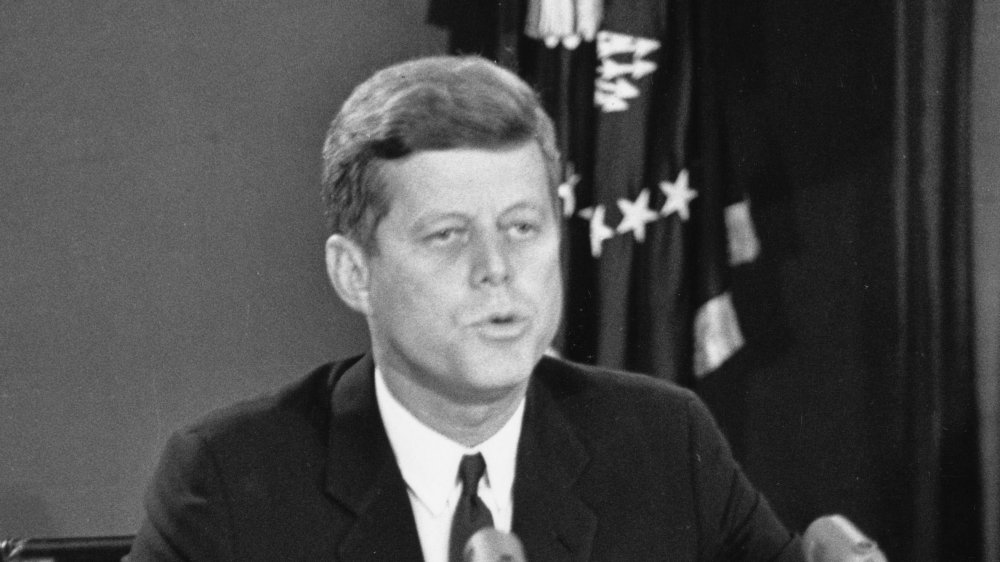

On October 15th, President Kennedy was made aware of the existence of the missiles. Faced with an imminent nuclear crisis, he immediately called together an executive committee of trusted advisors and officials. After the Bay of Pigs disaster, in which he had consulted only a small group of advisers, Kennedy was determined this time to consult a variety of experts, according to the BBC. Among the group were all the Joint Chiefs of Staff, National Security Council participants, Kennedy's speechwriter, the White House counsel Theodore Sorensen, a former ambassador to the Soviet Union, and the president's brother and attorney general, Robert F. Kennedy. Known as ExComm, the president's team began debating what the US government's next steps should be.

Kennedy had already raised the stakes by having previously publicly threatened that "the gravest issues would arise" if the Soviets ever installed offensive weapons in Cuba, via the BBC. Now he felt he could not back down from his former statements.

During the first day of the debates, ExComm members almost unanimously proposed the quick and decisive use of military force. Kennedy's Joint Chiefs of Staff declared the most effective course of action to be an immediate air strike on the missile sites, followed by a full-on invasion of Cuba. Other hawks agreed. Kennedy, however, feared that an aggressive response would lead to nuclear escalation.

Kennedy imposes a naval 'quarantine'

On October 17th, CIA Director John A. McCone declared the US had three options: "Do nothing and live with the situation, resort to an all-out blockade which would probably require a declaration of war and to be effective would mean the interruption of all incoming shipping," or "military action," via the Atomic Heritage Foundation. The debates went on for almost a full week, but by the third day, cooler heads were beginning to prevail. George Ball, the undersecretary of state, declared an invasion of Cuba to be "like Pearl Harbor. It's the kind of conduct that one might expect of the Soviet Union. It is not conduct that one expects of the United States," via the BBC.

In the end, Kennedy decided to take a more measured route. He would impose what was essentially a naval blockade on Cuba, which would prevent Soviet ships from bringing any more supplies onto the island. However, a naval blockade would be considered an act of war, so Kennedy was careful to call it a naval "quarantine" instead. While Kennedy saw this decision as a middle ground between military force and simply living with the situation, the hawks in the room saw the quarantine merely as a final ultimatum before an all-out invasion, according to the BBC. Kennedy sent his first in a series of letters to Khrushchev, alerting him to the quarantine and demanding he dismantle the missile sites and remove all nuclear weapons from Cuba.

'A deliberately provocative and unjustified change in the status quo'

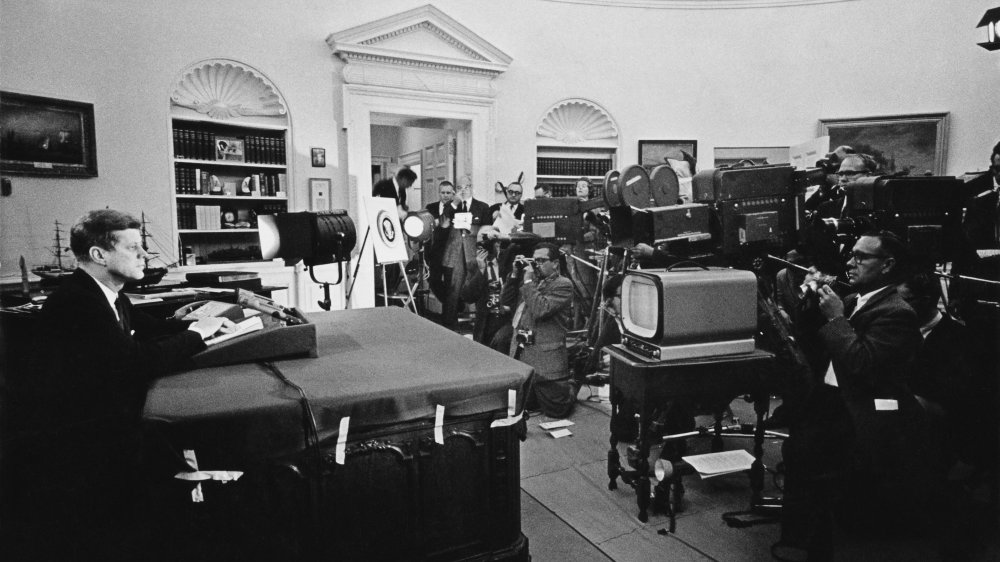

On October 22nd, Kennedy made a public address to the nation. Via a television broadcast, he alerted the world to the existence of nuclear weapons in Cuba. He explained the planned naval quarantine, making it clear that military retaliation would be the next option if the Soviet Union refused to comply.

In his speech, Kennedy declared: "Neither the United States of America nor the world community of nations can tolerate deliberate deception and offensive threats on the part of any nation, large or small. For many years, both the Soviet Union and the United States, recognizing this fact, have deployed strategic nuclear weapons with great care, never upsetting the precarious status quo which insured that these weapons would not be used in the absence of some vital challenge... But this secret, swift, extraordinary buildup of Communist missiles — in an area well known to have a special and historical relationship to the United States and the nations of the Western Hemisphere, in violation of Soviet assurances, and in defiance of American and hemispheric policy... is a deliberately provocative and unjustified change in the status quo which cannot be accepted by this country, if our courage and our commitments are ever to be trusted again by either friend or foe," via American Rhetoric.

The American public anxiously awaited the Soviet's response to this ultimatum. Some people were convinced nuclear war was imminent, and began hoarding food, gas, and supplies in preparation for a nuclear winter, per History.

'An act of aggression'

The naval quarantine of Cuba officially began the next day, on October 23rd. Despite Kennedy's strong speech, he began the first day of the quarantine by pushing the blockade line back by 500 miles, thus giving the Soviet ships more time to consider their next move, according to History.

On October 24th, Khrushchev responded to Kennedy's letter by telling him the naval quarantine was understood to be a blockade, and therefore the Soviet Union saw it as an "act of aggression," according to the Office of the Historian. Khrushchev also said he had ordered his ships to continue through the blockade to Cuba as planned. If the Soviet ships breached the quarantine, Kennedy would be forced to back up his speech with force, the result of which was likely to be an all-out escalation to nuclear war.

That same day, Kennedy's ultimatum was tested. However, despite Khrushchev's tough talk, most Soviet ships did in fact turn back around. At first, very few Soviet vessels attempted to breech the blockade. Those that did run up to the quarantine line were stopped by US naval forces, who determined they did not pose a threat. Because they were not carrying weapons, the US Navy permitted them to pass through the blockade.

'Maybe the war has already started up there ...'

However, another drama was unfolding just below the surface of the water. A Soviet B-59 submarine, equipped with a T-5 nuclear-tipped torpedo, had received no communication from above for several days, so they had no idea the blockade had begun. To make matters worse, they had no air conditioning, their battery was failing, and temperatures and tensions were rising on board, per the Atomic Heritage Foundation.

The American ships began dropping practice depth bombs around the B-59. They were intended to serve as a warning, but with no communication from Moscow, the ship's captain, Valentin Savitsky, believed that war between the US and Soviet Union had already begun. Savitsky reportedly declared: "Maybe the war has already started up there ... We're gonna blast them now! We will die, but we will sink them all—we will not become the shame of the fleet," via National Geographic. His second in command agreed.

However, all three senior officers on board the submarine were required to agree before the torpedo could be launched. The submarine's Chief of Staff, Vasili Arkhipov, held out. He insisted they wait until they emerged and received orders from Moscow before they deployed the weapons. His level head and calm reasoning eventually swayed the rest of the crew, and the weapons were never launched, thus saving the world from nuclear disaster.

DEFCON 2

While most Soviet ships had not attempted to breach the quarantine line, one vessel, the tanker Bucharest, refused to back down on October 24th. On October 25, two US naval vessels, the USS Essex and the USS Gearing, attempted to intercept Bucharest. However, they stopped short of outright seizing the ship. U.N. Secretary-General U Thant pleaded with both Kennedy and Khrushchev to "refrain from any action that may aggravate the situation and bring with it the risk of war," via History. Kennedy held off from taking immediate action, but he was becoming more convinced that the diplomatic route would fail. He feared the only way to remove the missiles from Cuba was to do it through military force.

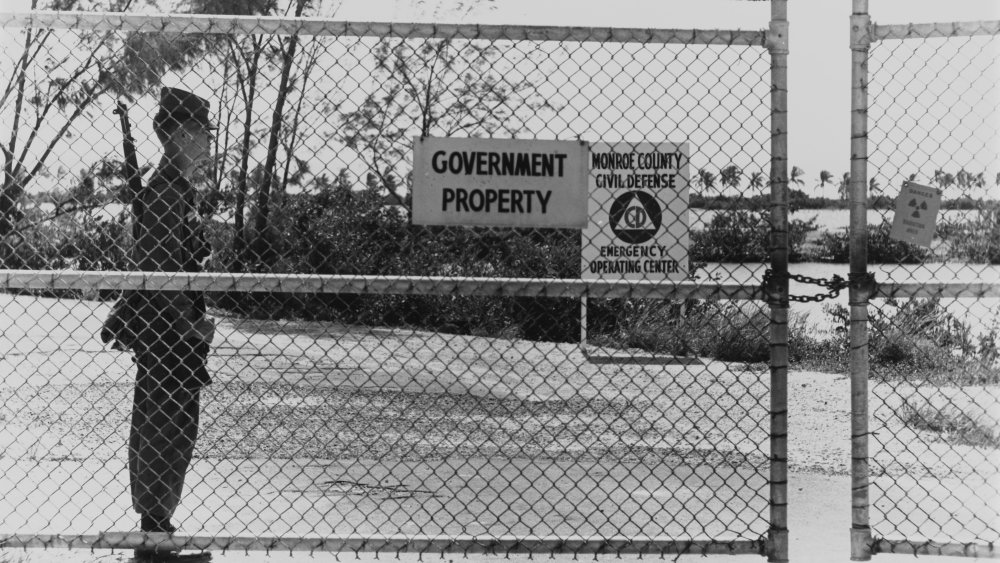

The next day, October 26, the US government learned that, in direct defiance of the demands set forth by the naval blockade, construction was continuing on nuclear missile bases in Cuba, per History. The US military then raised their readiness level to DEFCON 2, the highest state of military preparedness the US ever reached during the Cold War. US forces in Florida began preparing for an immediate invasion of Cuba. American B-52 bombers went on continuous airborne alert, and fully equipped B-47 medium bombers were strategically stationed across a variety of military and civilian airfields, ready to take off with just 15 minutes' notice.

An American plane was shot down over Cuba

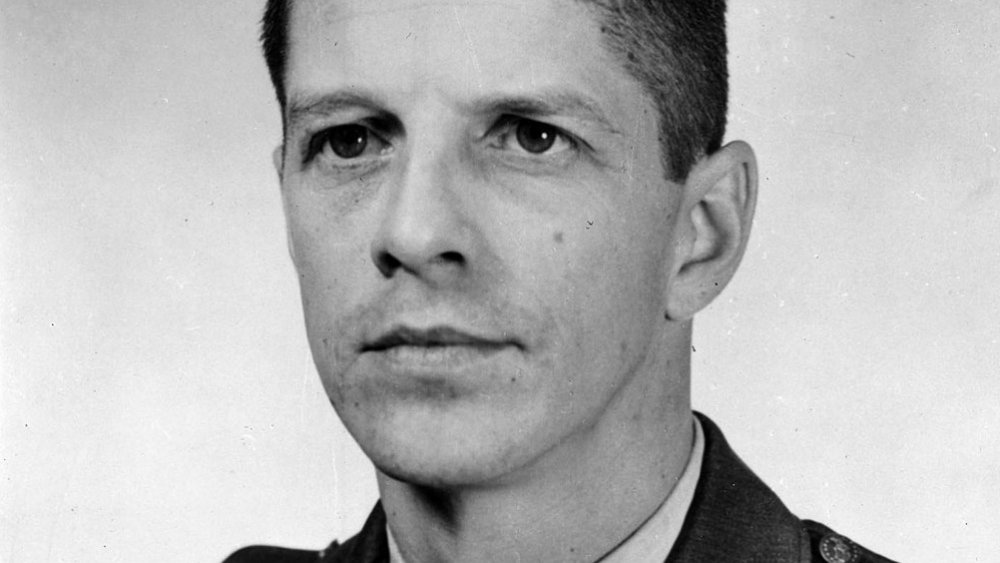

On October 27th, tensions were escalated even higher on the day that would come to be known as "Black Saturday." The US had been sending U-2 spy planes to conduct low-level photo-reconnaissance missions over Cuba, in preparation for a potential air strike. Major Rudy Anderson, a U-2 spy pilot, departed McCoy Air Force Base in Florida just after 9 am to conduct a reconnaissance flight over the eastern part of Cuba, according to History News Network.

However, a Soviet deputy commander, General Stepan Grechko, began tracking his movements as soon as his plane entered Cuban airspace. Anderson's plane had been labelled as "Target 33," and once the aircraft flew over the city of Banes, Grechko gave the order: "Target 33 is to be destroyed," via History News Network.

At 11:19 a.m., a surface-to-air missile struck the aircraft, and the plane went down. Major Rudolf Anderson was killed. He was the only casualty of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Despite pressure from his military advisers to retaliate, Kennedy decided once again to refrain from military action.

Negotiations bring an end to the crisis

On October 26th, Kennedy received a letter from Khrushchev, promising to remove the missile bases if the US government promised not to invade Cuba. While Kennedy was preparing to accept these demands, however, Khrushchev made another, public announcement on Radio Moscow, claiming the Soviet Union would be willing to dismantle their bases if America agreed to pull their nuclear missile sites out of Turkey. Not wanting to appear publicly weak, Kennedy refused to officially acknowledge the terms of Khrushchev's second declaration, per History.

However, he arranged for a clandestine meeting between Robert Kennedy and Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin. The attorney general agreed to remove the missiles from Turkey within five months, but only on the condition that that part of the agreement remain secret. Because Turkey was a member of NATO, the US didn't want to be seen undermining their alliance. Khrushchev agreed to those terms the next day.

Within a day of making the agreement, the Soviets began pulling their missiles out of Cuba. In a public statement, Kennedy expressed his "earnest hope that the governments of the world can, with a solution of the Cuban crisis, turn their urgent attention to the compelling necessity for ending the arms race and reducing world tensions," via the American Presidency Project.

A nuclear armageddon had been averted, but the nuclear arms race was far from over. The Cold War would drag on for almost another 30 years, but the world never again came as close to full-scale nuclear war as it had during those 13 harrowing days.