Letters That Changed The Course Of History

The written word is a powerful thing. You never know when something is going to spark an idea, a feeling, or a determination to do something that's going to change the world, and literally? That can happen at any time.

Don't think so? Just look at these letters: each one of them was composed by someone who sat down to write something they deemed important, worthy of setting pen to paper. Worth the effort of putting into the mail, and here's the thing: when each one of these letters reached their destination, they did something incredible. They changed the world.

History is a strange thing, a course of events that can go veering off in another direction at the flap of a butterfly's wings... or, it turns out, at the unfolding of a letter. How different would our world be if these people had never started to write? In some cases, it's easy to see how the world might have been better. But in others? It might have been much, much worse.

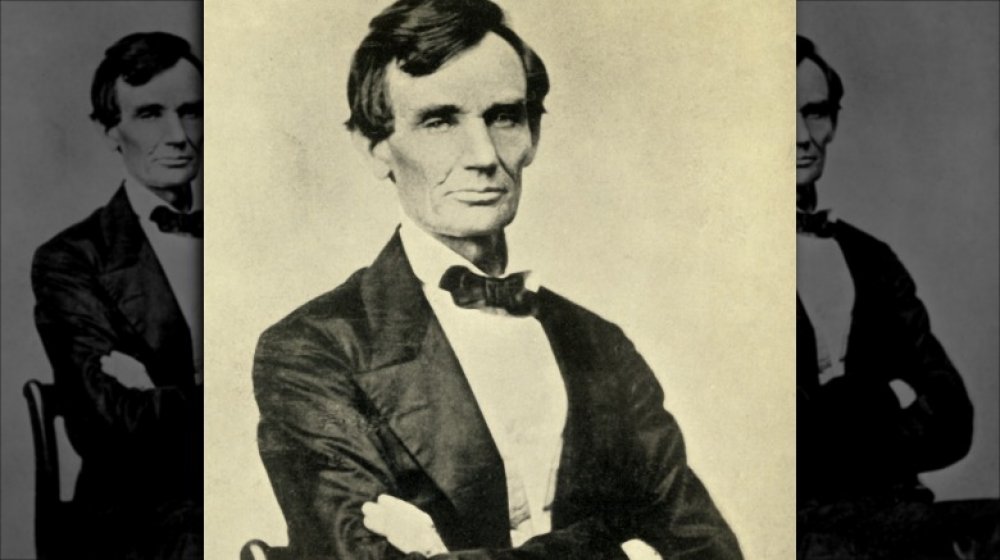

Abraham Lincoln's beard

Abraham Lincoln is one of the most recognizable of presidents, and it turns out that the only reason he grew his distinctive beard was because of a letter from an 11-year-old girl. In 1860, Grace Bedell wrote to him (via Time): "[...] if you let your whiskers grow [...] you would look a great deal better for your face is so thin. All the ladies like whiskers and they would tease their husbands to vote for you and then you would be President."

Lincoln took her suggestion to heart, and grew a beard. While he was on his way to his inauguration in 1861, he arranged to stop near her hometown of Westfield, New York, so he could see her. She'd later remember that he shook her hand and told her, "You see? I let these whiskers grow for you."

Did the letter change the world? According to Biography, Lincoln had a major image problem pre-beard. He was called everything from a "horrid-looking wretch" to the "most ungainly mass of legs, arms, and hatchet face ever strung upon a single frame." Couple that with photographs that couldn't capture Lincoln's friendly, approachable personality, and it was a recipe for campaign disaster. It's also been suggested his new beard saved his life: on that same trip to his inauguration, he was the target of an assassination plot. He — and his lone bodyguard — made it safely: in part, because of the "disguise" he was suddenly sporting.

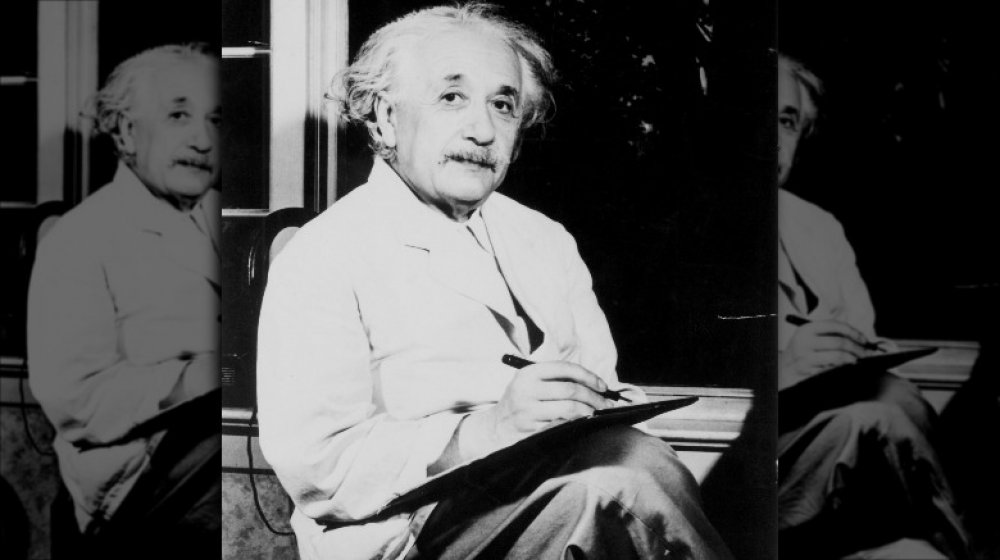

Einstein kick-starts the atomic age

The dropping of the atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki is one of those landmark events that changed the world forever. Ever wonder how they got the idea? Thank Albert Einstein.

The letter was dated August 2, 1939, and it was an appeal to FDR. Einstein wrote that he had become convinced that recent research surrounding uranium would lead to the development of new energy sources, with the proper backing. He also wrote (via the Atomic Heritage Foundation): "The phenomenon would also lead to the construction of bombs, and it is conceivable [...] that extremely powerful bombs of a new type may thus be constructed. A single bomb of this type, carried by boat and exploded in a port, might very well destroy the whole port together with some of the surrounding territory."

The letter didn't make it onto FDR's radar until October of that year, but it wasn't long before he established the advisory Uranium Committee, which the Office of History and Heritage Resources says was the first step on the path to setting up the Manhattan Project and developing the atomic bomb.

Einstein later regretted the role he played in setting the atomic age in motion, writing: "Had I known that the Germans would not succeed in developing an atomic bomb, I would have done nothing for the bomb."

The great reveal of the existence of the Flying Spaghetti Monster

Pastafarians! They're hilarious, right? They wear colanders and have religious holidays built around pirates, and seriously, who can't get on board with that? But here's the thing: at a glance, it seems pretty insane. But the roots of Pastafarianism — otherwise known as the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster — made a huge impact on how we look at school curricula.

It started in 2005, when Bobby Henderson wrote a letter to the Kansas Board of Education. They were looking into adding "intelligent design" — which Discovery Institute says is the idea that life was created by an intelligent force with specific goals — to what was being taught in schools. Henderson wrote that any "scientific" arguments put forward on intelligent design could just as easily apply to a flying spaghetti monster, stating (via The Guardian): "I fully expect, then, that this FSM theory will be admitted into accepted science with a minimum of apparently unnecessary bureaucratic nonsense, including the peer-review process."

The school board ignored the letter, but the internet loved it. It wasn't just a silly idea. The Conversation says that it did some major things: it made society look again at how we define a religion, and whether or not any and all religions have a place in public funding. Suddenly, the answer wasn't so clear.

Just some time off... to run for president

January 30, 1933. It's one of those days that was a pretty big deal, but one that we don't really remember these days: it was the day Hitler — fuhrer of the Nazi Party — was named chancellor of Germany. History calls his previous year "meteoric," and it was. German citizens still struggling in the aftermath of World War I were psyched about the promises of a new leader... who saved the really dark stuff for later.

What letter are we talking about, then? On March 1, 1932 — just days after getting his German citizenship — Hitler wrote a letter to his bosses. He was working in what The Guardian described as a "minor administrative role" at the state of Brunswick when he asked for some time off to run for office.

He wrote: "I hereby request leave of absence to the end of time for the selection of the next President of the Reich, Yours Faithfully, Adolf Hitler."

Remember, remember, the 5th of November

On November 5, 1605, the entirety of the English government could have disappeared... with one massive bang. That was the day of what's now called the Gunpowder Plot, and the goal was to take out not just King James I, but all of Parliament, too. Why? The rebels wanted to put an end to the relentless persecution of Roman Catholics.

The Gunpowder Plot failed, of course — it was about midnight on November 4 that Sir Thomas Knyvet found Guy Fawkes — and 36 barrels of gunpowder — in a cellar of Parliament (via History). How'd he know to look? A letter, sent to Lord Monteagle, shortly before that opening day of Parliament. The anonymous letters warned (via The National Archives): "[...] I would aduyse (advise) you as you tender your life to devise some excuse to shift your attendance at this parliament, for God and man had concurred to punishe the wickedness of this tyme." In other words? Get thee out of Dodge, because fiery vengeance is a-comin'.

Monteagle didn't get out of Dodge, he went right to the spymaster of James I, Robert Cecil. The plot was discovered, King and Parliament were saved, and Monteagle was gifted some land and a generous pension. As for who wrote it? No one is sure, but according to The History Files, there were always whispers it was written by Monteagle himself.

Pushing aside the Iron Curtain

The Cold War could have escalated at any time, and that's terrifying. Samantha Smith thought so, too, and in 1982, she asked her mother if there was going to be a war. Her mother, Jane, explained the situation to the 10-year-old, and suggested she should write to the Soviet's then-leader Yuri Andropov. So, she did, writing (via The Independent): "I have been worrying about Russia and the United States getting into a nuclear war. Are you going to vote to have a war or not? If you aren't please tell me how you are going to help to not have a war. [...] God made the world for us to live together in peace and not to fight."

She found out her letter had been published in a Russian paper, but she was disappointed that she hadn't gotten a personal response... so she wrote to him again, and he answered: "No one in our country [...] want either a big or 'little' war. We want peace." Then, he invited her to Russia, to meet the ordinary people who were just like her. Smith and her family went. (Smith is pictured on the trip. But she didn't meet Andropov, who was in the hospital where he would die shortly after.) While the highly publicized visit didn't stop the Cold War, it is credited with bringing a new perspective to the public on both sides: American or Soviet, children are children, and we're not so different after all.

Tragically, Smith and her father would die just three years later, in a plane crash.

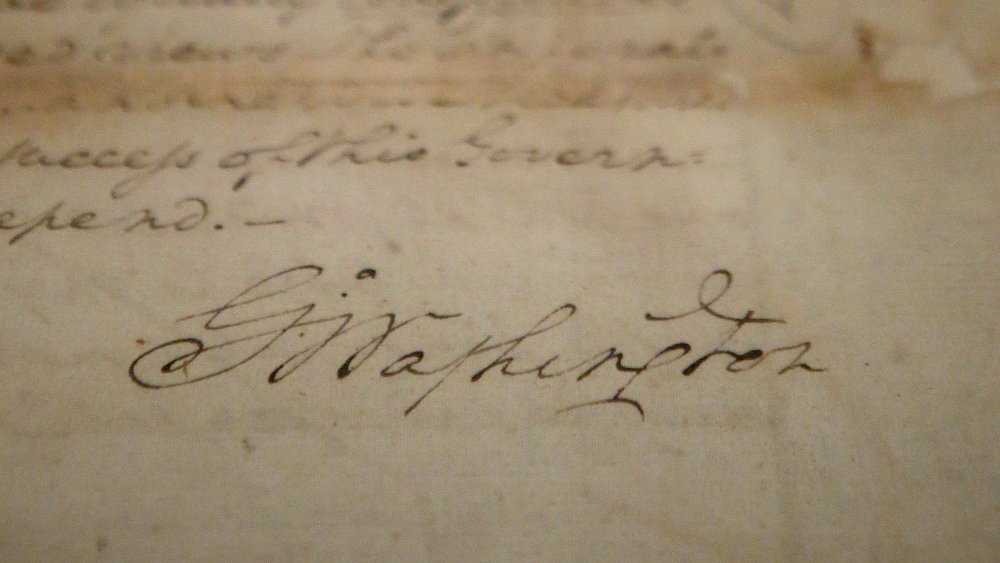

Sure, it's 'ungentlemanly,' but... eh!

Desperate times, they say, call for desperate measures — and there was a time during the American Revolution that was seen as being very desperate times, indeed. The British held New York City and the port, so Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, George Washington asked for some volunteers to sneak into New York City and find out what was going on.

The first — an army man named Nathan Hale, who's now got a statue standing outside of CIA headquarters — volunteered, only to be captured and hanged within the week. So, Washington wrote a letter.

It was to a merchant named Nathaniel Sackett. Sackett had an unlikely but valuable skill set: he was extremely good at coded messages. But... he wasn't great at much else, and was fired within six months. It was his replacement — Benjamin Tallmadge — who set up what National Geographic says was the organization that essentially won the revolution: the Culper Spy Ring. The spy ring was credited with exposing British spies, sabotaging aid missions, and stopping counterfeiting plans, funneling a huge amount of information back to the American rebels. No spies were ever caught and, in fact, they were so good that it wasn't until the 1900s that anyone even knew they existed.

How can you preach freedom when you own slaves?

America's Bill of Rights was all about liberty and freedom and all kinds of buzzwords still in use today, but for many people living in America, there was a huge problem: the white men who wrote that Bill of Rights owned other men. That's... the exact opposite of freedom. And one man called Thomas Jefferson on his hypocrisy: Benjamin Banneker, a free black man who was a mathematician, scientist, civil engineer, astronomer, and philosopher.

He absolutely let Jefferson have it. In 1791, he quoted the Bill of Rights' ideals about equality, then wrote (via the National Archives): "Sir how pitiable it is to reflect, that altho you were so fully convinced of the benevolence of the Father of mankind [...] that you should at the Same time counteract his mercies, in detaining by fraud and violence so numerous a part of my brethren under groaning captivity and cruel oppression, that you should at the Same time be found guilty of that most criminal act, which you professedly detested in others."

Jefferson did write back, but Facing History notes that he treated Banneker as something of an abnormality, and referred to the widespread theories of racial superiority. While Banneker never got Jefferson to change his mind, he did reach others: Banneker bound and published both his letters and Jefferson's responses in an almanac that circulated around the world, and became incredibly important among anti-slavery campaigners and abolitionists.

Please save us

John F. Kennedy may have served a rather short time as president, but his impact is indisputable. It may never have happened if it weren't for a very, very short letter, chiseled into the shell of a coconut. It started on August 2, 1943. Kennedy was in the South Pacific, at the helm of a patrol torpedo boat (far right, with crew). That boat was rammed by a Japanese destroyer, and what followed was nothing short of incredible: JFK swam to the relative safety of an island three miles away, and he did it while dragging a crewmate by the strap of his life jacket.

That island was uninhabited, and when Kennedy and his crew regrouped, they set out for a larger island. That, too, was uninhabited, but they soon stumbled across two men from the Solomon Islands. According to the Smithsonian, JFK etched a message into the shell of a coconut, saying: "NAURO ISL... COMMANDER... NATIVE KNOWS POS'IT... HE CAN PILOT... 11 ALIVE... NEED SMALL BOAT... KENNEDY" and gave it to the men, who bravely carried it through Japanese-occupied waters to the Allies. Kennedy and his crew were rescued, and the coconut was the only reminder of his service he kept post-war.

When one of the islanders who saved him died in 2014 at 93-years-old, his family remembered (via the BBC) that they had been invited to Kennedy's inauguration (but didn't attend), and that Kennedy had called him his "honorary chief."

'Be a good boy'

The 19th amendment, says Time, was just 39 words long. Bit it was a big deal: it laid the groundwork for women's right to vote. Tennessee was the last state to ratify the amendment. The date was August 18, 1920, and legislators walked into the statehouse gallery wearing a rose on their lapel. A red rose meant they were going to vote against it, while a yellow one meant they were voting for it. There were 96 lawmakers in attendance, and exactly half wore red roses. If that half had voted according to the rose they'd pinned to their jackets, the amendment would have been defeated.

That didn't happen, so... what did? When the call for votes got to 24-year-old Harry T. Blum and his red rose, he paused. In his jacket pocket was a letter from his mother, Febb Burn. She wrote of her support for women's suffrage, and ended her letter with (via The Washington Post): "Don't forget to be a good boy and help Mrs. 'Thomas Catt' with her 'rats.' Is she the one that put rat in ratification? Ha! No more from Mama this time. With lots of love."

It wasn't an easy choice to make: Burn's mentor was Sen. Herschel Candler, who was incredibly outspoken when it came to his belief that women and minorities shouldn't be allowed to vote. But when Burn's name was called, he took off his red rose, voted "aye," and the amendment passed.

Secret letters from hell on earth

The horrors of life in the Nazi concentration camps of World War II is no secret today, but at the time, getting word out of the camps wasn't just almost impossible, it was dangerous. Letters did go in and out, but they were — unsurprisingly — censored. But four incredibly resourceful women did get some letters out of Ravensbruck and to their families.

The plan was hatched by four Polish Girl Guides — Wanda Wojtasik, Janina Iwanska, Krystyna Iwanska, and Krystyna Czyz — who had landed in the camps for their association with the Polish Underground. They were allowed one letter per month, and knowing whatever they wrote would be read by SS guards, they wrote two letters: one was in regular ink, and the other was in urine that would dry and become invisible until it was heated. One alerted her brother — via a cleverly disguised message — that there was a secret code in their letters, and then they used the invisible writing to provide details on the medical experiments that were done on them, the mass executions, and the women who were sent to work in the concentration camps' brothels.

The letters traveled first to the Polish resistance, then The First News says they ended up in the hands of the Vatican, the Red Cross, and the Polish government-in-exile. All four women survived, and saw their letters used as evidence at the trails in Nuremberg, where 11 of the Ravensbruck SS guards were handed a death sentence.

The plot to kill a queen

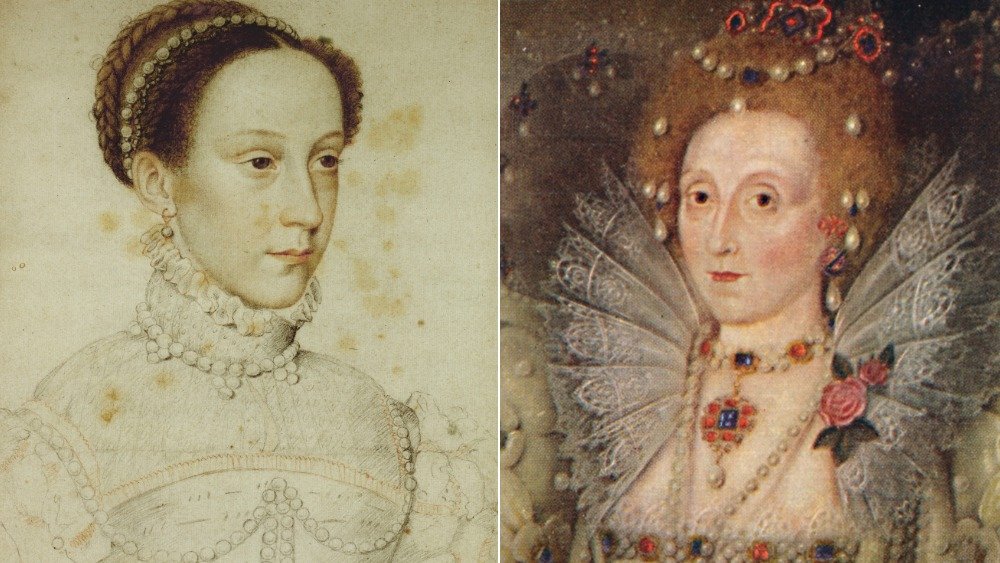

The conspiracies of the English court around the time of Elizabeth I are so insanely complicated that it's enough to make your head hurt, so here's the basics: Mary, Queen of Scots (left), had a whole bunch of supporters that wanted to kill Elizabeth I (right) and put Mary on the throne instead (via The History Press). That might seem like the kind of thing you wouldn't want to put into a letter, but in 1586, Anthony Babington did exactly that. The letter detailed what's now known as the "Babington Plot," and exactly what that is doesn't really matter... especially considering it sort of had the reverse effect.

Babington and his co-conspirators had a plan to assassinate Elizabeth and put Mary on the throne, which is damning enough. That letter was sent on July 6, and on July 17, The National Archives says that Mary wrote an even more damning response: she wrote about her acceptance of every part of the plan.

The second letter was, of course, intercepted, and the NSA says it was such a nail in the coffin, so to speak, that the man who intercepted, coped, and sent it to Elizabeth's spymaster, Francis Walsingham, included a fun little drawing of a gallows on his copied version. Mary was arrested within the week, and wasn't sent to the gallows: she was beheaded, and anti-Catholic sentiment continued.