The Tragic True Story Of The Boxer Rebellion

One of the largest anti-foreign uprisings in China's history, the Boxer Rebellion (also known as the Yihetuan Movement) started off as a peasant uprising. As the uprising gained momentum, they were supported by the Qing government, but ultimately, it was this support that would lead to the disintegration of China's last dynasty in 1912.

As foreign imperialist powers sought to increase their influence and interests in China during the 19th century, resentments against foreigners, especially foreign missionaries and Chinese Christian converts, began to bubble. The building of railroads was also seen as an imperialist imposition, and when worse and worse droughts began to occur, the Chinese thought that it was God's wrath in response to the harm that was being inflicted on China's land. It was claimed that railroads had hurt the "dragon's vein" and that the mining in the mountains had let out "the precious breath," tarnishing the harmony between nature and man.

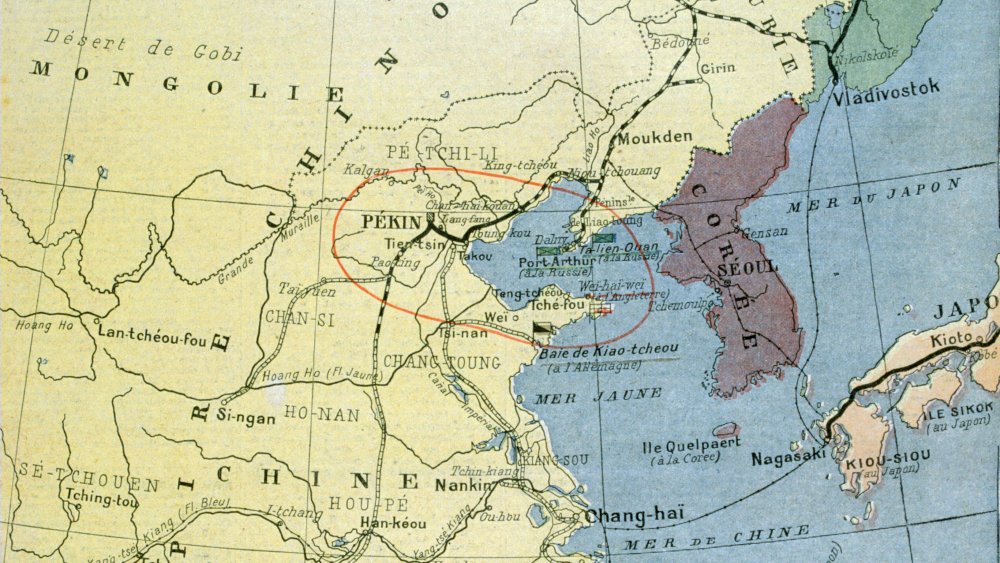

By 1900, there were violent attacks across China, especially in Inner Mongolia, Manchuria, and the provinces of Shanxi, Zhili, and Shandong. The Boxer Rebellion has been called a patriotic movement, a rebellion, or an uprising, depending on who's referring to it and whether they wish to portray it in a positive or negative light. In the end, the Boxer Rebellion led to the Boxer Protocol, which, ironically, expanded the presence and power of foreign imperialists in China. This is the tragic true story of the Boxer Rebellion.

Simmering resentments leading up to the Boxer Rebellion

Tensions were already running high leading up to the Yihetuan Movement. Shandong, where the Yihetuan originated, was known for its extreme weather and alternating cycles of flooding and drought. According to the University of Bristol, between 1896 and 1899, the region experienced particularly devastating flooding that ruined large areas of Shandong, affecting thousands of villages and over 34 counties.

In 1899, the other extreme hit as the region began to experience a period of intense drought. According to The Boxer Rebellion and the Great Game in China by David J. Silbey, in July 1900, the rainfall at Qingdao in Shandong was roughly five percent of the expected monthly precipitation. This drought was interpreted by the Yihetuan as a sign of God's wrath in response to the imperialist presence in the Chinese Empire.

Starting in the 1840s, the British, Americans, French, Dutch, German, Japanese, and Spanish had started to take control of large parts of the Chinese Empire through various treaties. Relations between foreigners and native Chinese were increasingly strained leading up to the Yihetuan Movement, though foreign missionaries were a particular source of agitation due to their day-to-day involvement in the Chinese Empire.

This was seen in the Juye Incident on November 1, 1897, when two German missionaries were murdered in the middle of the night at a missionary residence in Zhangjiazhuang. This event led to Kaiser Wilhelm's occupation of Jiaozhou Bay, which, in turn, led to Russian, British, Japanese, and French occupations of various regions in the Chinese Empire.

Who were the Boxers?

As the presence of foreign imperialists and Western missionaries grew, so did the resentment among local Chinese people. They believed that the Western missionaries were only protecting Christian converts and their own interests. They also especially disliked how Western missionaries were able to bypass local authorities since they were exempt from various local laws.

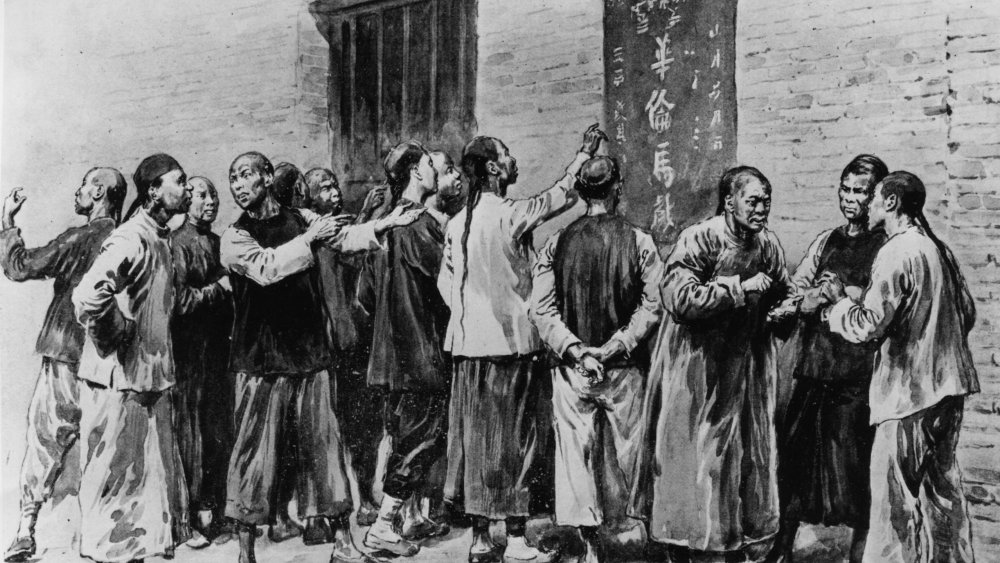

According to the San José State University, the Yihetuan, or Boxers, arose out of a Chinese secret society that was itself an offshoot of the Eight Trigrams Society. The society's name translated to "The Righteous and Harmonious Fists," and they engaged in martial arts training with the belief that it would make them invulnerable. The name "Boxers" was given to the group by English-speaking missionaries who utilized the only comparatively equivalent word they had for martial artists.

Initially, the Yihetuan were against the Qing dynasty in addition to being anti-foreigner. But in 1898, after anti-foreign conservatives gained control of the Chinese government, they convinced the Yihetuan to join with the Qing in opposition against the foreigners. Their slogan became "Support the Qing, destroy the foreigners." According to The Boxer Uprising: A Background Study by Victor Purcell, the Yihetuan garnered support from the peasant population against the foreign missionaries, who were considered "Primary Devils," and the local Chinese Christian converts, who were considered "Secondary Devils."

Support for the Boxers from Empress Dowager Cixi

After the Hundred Days of Reform that Emperor Guangxu attempted to institute, conservative officials essentially instituted a military coup in order to return Empress Dowager Cixi to power. Empress Dowager Cixi promptly reversed the reforms, and in 1899, influenced by the conservative officials in her court, she began to slowly express support for the anti-foreign Boxers.

This came to a head in 1900, when the Imperial Court issued several edicts that tacitly supported the Yihetuan Movement. According to Alpha History, Cixi believed that the Yihetuan might be beneficial in driving foreign imperialists out of China. As a result, the Imperial Court issued edicts in January and April of 1900 that legalized civilian militias. They also endorsed Yihetuan recruitment and allowed money to go toward Yihetuan leaders for training.

Empress Dowager Cixi also went so far as to repudiate the foreign influence in China, stating that, "For the past 30 years [the foreigners] have taken advantage of our country's benevolence and generosity, as well as our whole-hearted conciliation to give free rein to their unscrupulous ambitions." According to Historicizing Online Politics by Yongming Zhou, Cixi was so frustrated by the imperialist powers' efforts to control her and ignore her commands that she declared war on all foreign powers.

Attitudes toward the Boxers within the imperial court

Despite Empress Dowager Cixi's support for the Yihetuan Movement, throughout this time there were many quarrels within the Imperial Court between pro-foreign, anti-Yihetuan factions and anti-foreign, pro-Yihetuan factions. According to The Boxer Uprising by Victor Purcell, on June 16, 1900, Empress Dowager Cixi convened a meeting of the Imperial Council that was attended by all the Manchu nobles, dukes, princes, and high officials.

During this meeting, there was a violent debate between the two factions, caught between the options of pacification and annihilation. Despite the fact that several opponents to the Yihetuan had been replaced by pro-Yihetuan officials, there was still dissent in the Imperial Court.

Unfortunately, some who voiced their opinions during this meeting wouldn't end up living to see the Yihetuan Movement come to fruition. According to The Origins of the Boxer Uprising by Joseph W. Esherick, Yuan Chang, who was a minister of the Zongli Yamen, expounded on his views that the Yihetuan were mere rioters. He would later be executed for his anti-Yihetuan sentiments. Ultimately, the Imperial Court recognized the fact that the Yihetuan had the popular support of people in the countryside. To advocate suppression of the Yihetuan meant risking the support of the people.

The Seymour Expedition

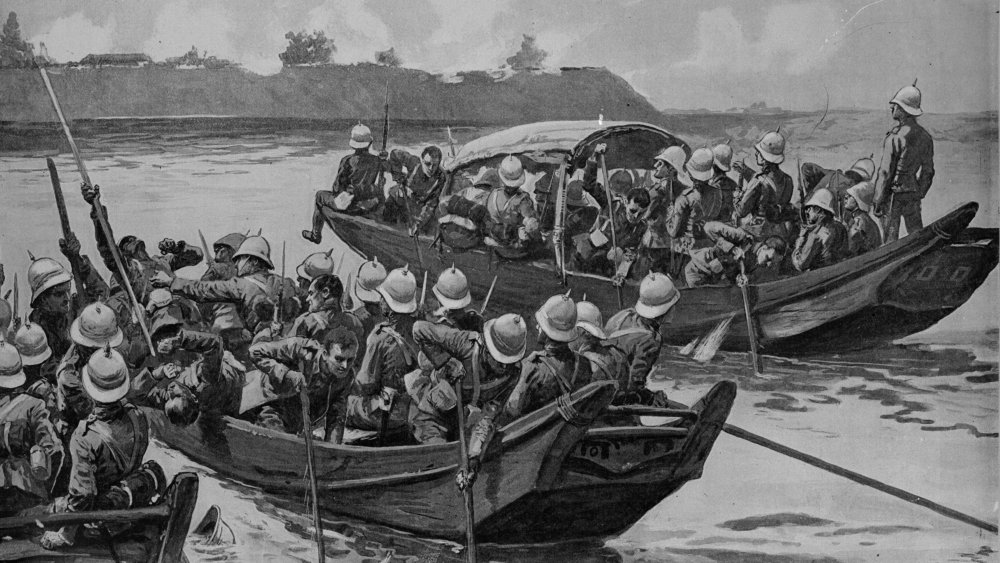

In response to the Yihetuan Movement, the imperialist foreign powers banded together to create the Eight-Nation Alliance. The United States, Great Britain, Russia, Japan, Italy, Germany, France, and Austria-Hungary formed an alliance and quickly dispatched their troops to subdue the uprising. According to ThoughtCo, on June 10, 1900, a group of 2,000 Marines under the command of British Vice Admiral Edward Seymour were dispatched from Takou toward Beijing.

They went by rail to Tianjin but soon realized that the Yihetuan had cut the rail line to Beijing. They continued on foot but only got as far as Tong-Tcheou before they were forced to retreat due to pushback from the Yihetuan. According to the United States National Archives, Seymour's expedition was less than 25 miles away from Beijing when they were forced to turn back. By June 26, Seymour's column was back at Tianjin and had suffered 350 casualties.

The Seymour Expedition was ultimately doomed to fail. According to "The China Relief Expedition," officers in Tientsin already knew about the damaged rail line, and thus, Seymour would've ultimately known as well. Seymour also failed to account for the additional rations they'd need due to this delay and instead brought barely enough rations for three days. According to The Origins of the Boxer War by Lanxin Xiang, Seymour's defeat ended up bolstering the status of the Boxers in addition to strengthening the determination of the Imperial Court in their resistance to imperialism.

Ordering the imperialists to leave

The Seymour Expedition infuriated Empress Dowager Cixi. According to "The China Relief Expedition," soon after, she also received what was most likely a forged document that claimed to list the demands of the Eight-Nation Alliance, which increased her wrath. The document was most likely created by Prince Tuan in an attempt to goad her into a declaration of war. In response to this attempted invasion of Beijing, on June 20, Cixi ordered all foreigners, along with diplomats, to leave Beijing under escort by the Chinese army.

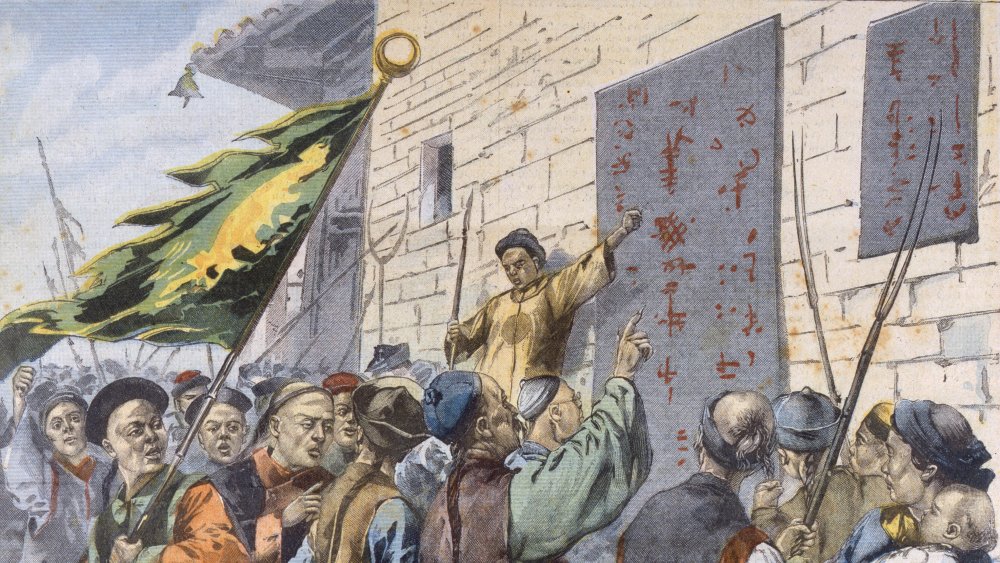

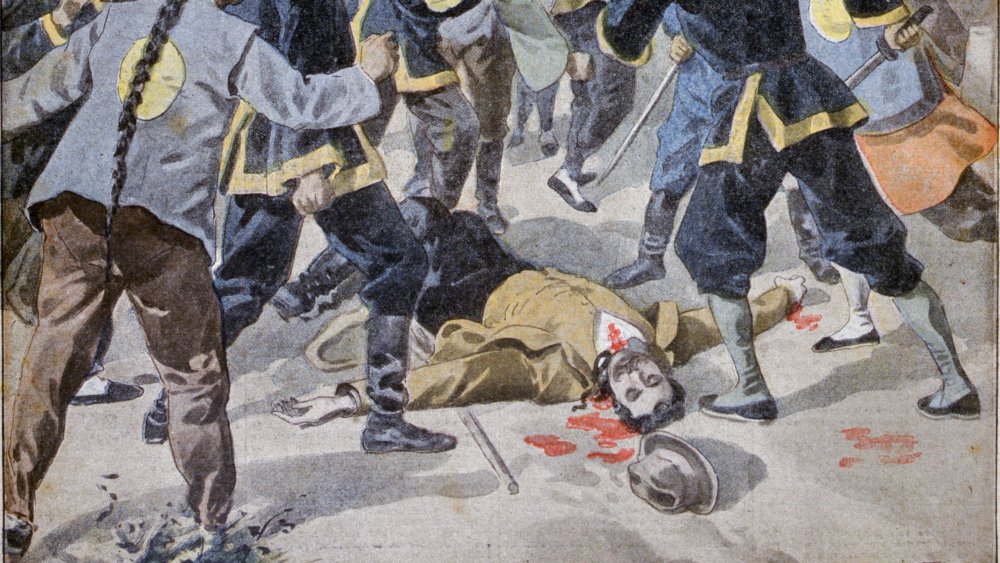

According to MIT, on the same day, the German minister Baron von Ketteler was killed in the streets after he murdered a Chinese boy. In response to the minister's death, foreign officials declared that they planned on remaining in the city until the troops of the Eight-Nation Alliance arrived in Beijing. Enraged at the refusal of foreigners to leave the capital, Cixi put the full weight of her support behind the Yihetuan Movement and made her official declaration of war on June 21, 1900. Endorsing the Yihetuan for their patriotism, Empress Dowager Cixi allowed them to run rampant in the city, putting up flyers advocating for the slaughter of Chinese Christians.

In light of this declaration, Chinese Christians and foreigners in Beijing fled to the Legation Quarter and constructed a defensive perimeter. The Yihetuan and Chinese army tried various methods to infiltrate the Legation Quarter, including burning them out, but the compound held fast.

Two years of violence

From 1899 to 1901, the Yihetuan Movement claimed thousands of lives. According to The Alliance, over 200 foreign missionaries were slaughtered in the summer of 1900 alone. It's unclear exactly how many people were killed during the Yihetuan Movement, but estimates range as high as 100,000. According to The Guardian, many of the missionaries who were slaughtered were based in the Shanxi province.

In History in Three Keys, Paul A. Cohen and Paul A. Townsend write that while the spread of disorder escalated after the Imperial Court announced their declaration of war, the levels of violence varied depending on how sympathetic provincial and local authorities were toward the Yihetuan.

The majority of the violence was during the summer of 1900, when over three quarters of the total deaths occurred. Roughly 3,000 military personnel were also killed in combat, the majority of whom were Yihetuan or other Chinese fighters. According to SciencesPo, many Chinese people who were unaffiliated with the Boxers or the foreigners were also caught in the crossfire. Some Chinese women reportedly even committed suicide in order to avoid capture and rape by foreigners.

The canonization of Mitrophan

Many of the Chinese Christians who died during the Yihetuan Movement became known as the Martyr Saints of China when they were canonized by the Catholic Church. According to the American Carpatho-Russian Orthadox Diocese of the U.S.A., on June 10, 1900, leaflets were posted in the streets calling for the massacre of Christians.

Many fled for their lives or hid in the home of their local priest. One such priest was Father Mitrophan Tsi-Chung (also referred to as Metrophanes), who had been ordained by St. Nicholas of Japan. Mitrophan sought to hide Chinese Orthodox Christians in his home, but the armed Yihetuan surrounded them that night. While some people were able to escape, most were impaled or burned alive, including Mitrophan.

According to the Orthodox Christian Mission Center, Father Mitrophan was the first Orthadox Chinese priest and one of the hundreds of Chinese to be martyred. Mitrophan and his fellow martyred Chinese Orthadox Christians ended up being canonized in 1902 by the Orthadox Church, setting their feast day on June 11 in commemoration of their slaughter. Interestingly, while the Chinese government had little response to the Orthodox canonization, when the Vatican canonized 120 Chinese martyrs in 2000, they were met with strong condemnation from China.

A tragic loss of knowledge

During the siege against the Legation Quarter, the Yihetuan and Chinese army repeatedly tried burning out the foreigners. During one of their attempts at burning out the British Legation, the fire went out of control and spread into the buildings of the Hanlin Yuan Academy, which was next to the Legation. According to "Destruction Of Chinese Books In The Peking Siege Of 1900" by Donald G. Davis Jr. and Cheng Huanwen, the Hanlin Yuan Academy was a university comprised of a series of courtyards and buildings, which also included a library that housed "the quintessence of Chinese scholarship ... the oldest and richest library in the world."

While there are disputes as to whether the Chinese set fire to the Hanlin or the British destroyed the library as a defensive measure, the loss of the library's unfathomable knowledge cannot be questioned.

According to "The China Relief Expedition," despite efforts by those in the Legation to extinguish the flames, almost the entire academy and its contents were destroyed. Unfortunately, since the contents of the Hanlin Library aren't known with certainty and there are no records of its collections, it's unclear what records and how many were ultimately destroyed in the fire. Tragically, what is known is that what was lost was irreplaceable.

The execution of Xu Jingcheng

During the Yihetuan Movement, Xu Jingcheng was one of six members of the Imperial Court who sent a petition to Empress Dowager Cixi urging her to find a diplomatic solution. Xu had been especially horrified at the executions of foreign diplomats and stressed that Cixi must cease support for the Yihetuan.

According to History of War, Xu served as a diplomatic envoy to a number of European countries for almost 30 years before the Yihetuan Movement. During his career, he had also converted to Roman Catholicism, which made many Yihetuan and pro-Yihetuan officials suspicious of his motives.

Upon reading their petition, Empress Dowager Cixi was furious and stated that Xu and the other ministers must be put to death for their dissent and for even sending such a ridiculous petition to the Imperial Court. According to History in Three Keys by Paul A. Cohen and Paul A. Townsend, Xu and four other officials were executed on July 28, 1900.

Infiltrating the Legation Quarter

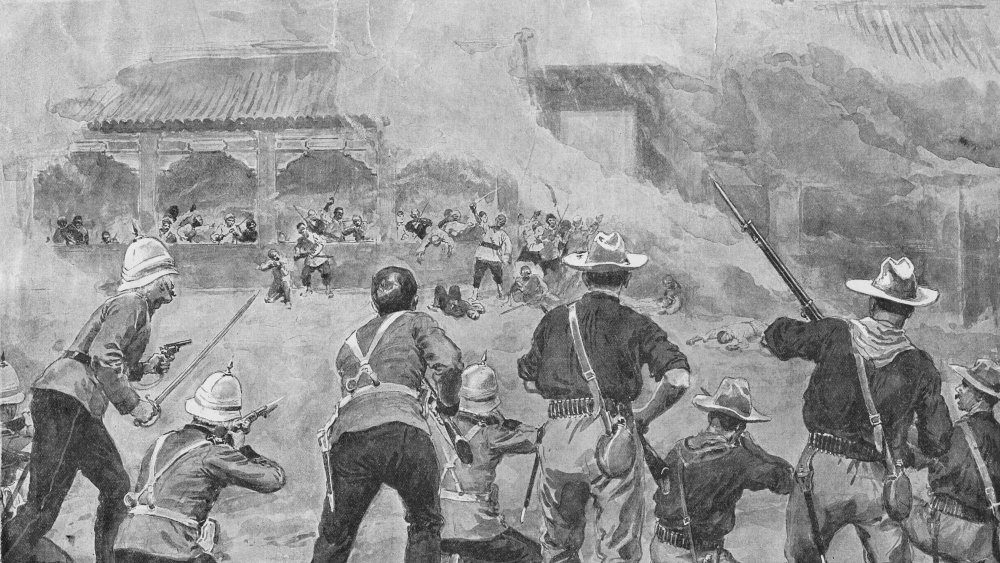

As the Eight-Nation Alliance continued to move toward Beijing, they were able to capture Tianjin on July 14, 1900, during their second attempt to rescue the Legation Quarter. According to ThoughtCo, the advancing international army, led by British Lieutenant-General Alfred Gaslee, numbered 54,000. Once they captured Tianjin, 20,000 pressed on toward Beijing.

It took a month to reach Beijing, but once they did, the Eight-Nation Alliance began an assault on the city's walls. In the early hours of August 14, the Russians were briefly able to breach the gate at Dongen, though they were soon overrun by Chinese forces. But according to OmniAtlas, by 4:30 PM, the American forces broke through into the Legation Quarter.

Since the United States already had Manila, Philippines, as a main army base, the U.S. was able to quickly dispatch multiple battalions for the various attacks. American soldiers in the 14th Infantry scaled the walls of Beijing and planted the American flag there, which, according to the U.S. Army Center of Military History, was the first foreign flag to ever fly in the city. Corporal Calvin P. Titus, the first to scale the wall, was later awarded a Medal of Honor. By August 15, the Eight-Nation Alliance had entered the Forbidden City.

Upon lifting the siege, the Eight-Nation Alliance proceeded to loot and kill in Beijing as much as the Yihetuan had been doing.

The evacuation of Empress Dowager Cixi

As the Eight-Nation Alliance infiltrated Beijing, Empress Dowager Cixi and Emperor Guangxu decided to flee the city. According to Noted, Cixi dressed up like a peasant in a blue cotton dress in order to avoid detection. But in their flight, they kept insisting that they weren't fleeing and were instead merely going on an "inspection tour" to Xi-an in the Shaanxi Province.

With the emperor and empress gone, the remaining top Qing officials signed the Boxer Protocol on September 7, 1901. According to ThoughtCo, the Boxer Protocol stated that the government had to pay 450,000,000 taels of silver as war reparations in addition to executing ten high-ranking leaders who had supported the Yihetuan. Russian forces also went on to occupy Manchuria, an act that led to the Russo-Japanese War in 1904, while German forces took Tsingtao.

Although Empress Dowager Cixi returned to Beijing in 1901 with the intention of modernizing China and making social reforms, it was too little, too late. The Qing Dynasty had been severely weakened by the Imperial government's defeat, and within 11 years, the last dynasty of China was overthrown.