The Amazing Life And Tragic Death Of Lon Chaney

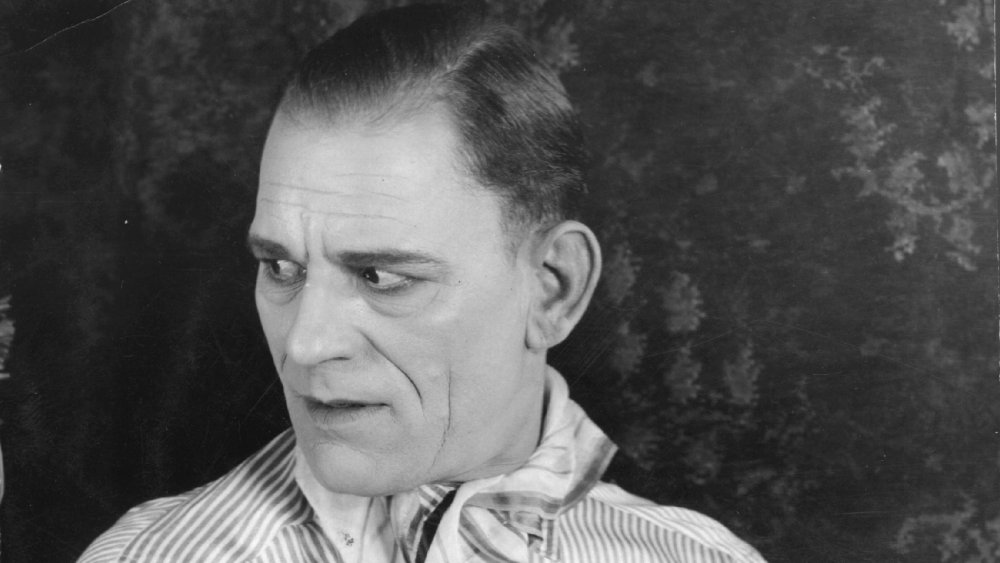

Although the genesis of horror cinema lies in the German Expressionist classics Nosferatu and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, the golden age of the genre as an American phenomenon begins in 1925 with the appearance of the first universally recognized movie monster, the Phantom of the Opera. The man behind the iconic makeup was horror's first superstar, Lon Chaney. Already well-established as the "Man of a Thousand Faces" prior to The Phantom of the Opera's release, Chaney's skills as a makeup artist combined with his mastery of physical expression made him not only the silent era's most important character actor but the prime influence on the development of cinematic special effects.

Despite Chaney's popularity and enduring influence, he remains a mystery. A private artist who, in Hollywood's classic age ballyhoo, avoided the public eye, Lon Chaney preferred to let his work speak for itself, with each performance and mind-bending physical transformation becoming part of his larger-than-life myth.

Unfortunately, Chaney, one of film's great visual artists, would not survive to see the medium into the age of sound. Dying of cancer a month and a half after the release of his only talkie, Chaney would take a lifetime of potential and innovation to the grave just as the movies took their next evolutionary step. From his humble beginnings on the stage to his rise to fame as a legend of the silver screen, this is the amazing life and tragic death of Lon Chaney.

Lon Chaney's extraordinary early life

Leonidas Frank "Lon" Chaney, born in Colorado Springs, Colorado, on April 1, 1883, faced a unique set of challenges in early life that would be instrumental in his development as an actor. His parents, Frank H. Chaney, a successful barber, and Emma Alice Kennedy Chaney, daughter of the founder of the Colorado School for the Deaf, were both hearing-impaired. Overall, Chaney claimed to have had a happy childhood. He had many friends, including brothers Noble, George, and Virgil Johnson, who would make their own mark on the film world as the founders of Hollywood's first all-Black film company.

Nevertheless, Chaney was forced to leave school in the fourth grade when his mother developed inflammatory rheumatism after giving birth to his brother George. Charged with caring for his bedridden mother and younger siblings while his father and older brother worked, young Lon Chaney developed his skill for pantomime. Entertaining his mother and relating the day's events to her without words, he became a master of communication through physical expression.

At 14, Lon's knack for entertaining found a paying outlet when he became a tour guide at Pikes Peak. About a year later, according to his biography, Chaney learned the trade of carpet laying and wallpaper hanging at the urging of his father. By this time, Chaney had worked as a stagehand in a local theater and appeared onstage in a few bit roles. However, he didn't consider acting a serious career option until some time later.

Lon Chaney's troubled marriage

In 1902, Lon Chaney found a way to incorporate his skills as a tradesman into his passion for the theater. As Chaney biographer Michael F. Blakes writes in his 1993 book Lon Chaney: The Man Behind the Thousand Faces, Chaney left his job as a wallpaper hanger and became a full-time stagehand at the Colorado Springs Opera House.

Soon, Lon Chaney was performing in popular traveling stage productions and vaudeville shows. While on the road in Oklahoma City, he met Cleva Creighton. Creighton, born Frances Cleveland Creighton, was a 16-year-old singer hoping to land a job as an entertainer with the company with which Chaney was touring. A whirlwind romance ensued, and the two were married. In 1906, the couple had their only child, a son they named Creighton Tull.

Lon and Cleva returned to touring theater and moved to California, where they appeared in productions in Los Angeles and San Francisco. Although Lon struggled to find success, Cleva worked steadily as a cabaret singer.

In 1913, after an argument with her husband over his decision to return to the road as the manager of the vaudeville team Kolb and Dill, Cleva Chaney attempted suicide by swallowing a vial of bichloride of mercury. Although she survived the attempt, she could no longer sing. Unable to continue in the marriage, Lon Chaney filed for divorce, citing his wife's infidelity, alcohol abuse, and unfitness as a mother. The court granted Chaney the divorce and awarded him custody of his son.

Chaney's makeup skills set him on the road to success

The dissolution of Lon Chaney's marriage and the scandal that followed nearly ended his career in the theater. Nevertheless, a new opportunity in the burgeoning medium of film quickly arose for the struggling actor. In 1912, Lon Chaney took a job with Universal Studios.

Although he was never cast as a lead in his early, uncredited work, Chaney often played featured parts that showcased his unique skills. Specializing in villainous, misshapen, or macabre roles, Chaney quickly gained a reputation as a solid character actor with a special talent for makeup.

In a tradition held over from theater, film actors were expected to design and apply their own makeup in the early days of the movie industry. Dedicated makeup departments were unheard-of until 1917. The extent of special makeup effects in film was limited to stage techniques consisting mainly of beards, wigs, and simple aging accomplished through highlighting and shading. To set himself apart from the competition, Chaney experimented extensively to create complicated, never-before-seen characterizations. Encouraging Chaney's gifts, husband-and-wife filmmaking team Joseph DeGrasse and Ida May Park employed the actor in 64 films between 1914 and 1918. According to Chaney biographer Michael F. Blake, Chaney's reputation as a master of makeup caught the eye of the entertainment press as early as 1916, when his work was featured in both Motion Picture Weekly and Photoplay Journal.

The rise of the man of a thousand faces

By 1918, Lon Chaney had appeared in over 100 films for Universal and was quickly establishing a reputation among his peers and the public as a singular talent. Chaney was a star on the rise. Nevertheless, Universal refused to pay Chaney a salary equal to his value. When he approached studio executive William Sistrom for a raise, Chaney received a resounding "no" couched in an insult. According to Robert Gordon Anderson, author of Faces, Forms, Films: The Artistry of Lon Chaney, Sistrom bluntly told Chaney that he was just another actor and would never be worth more than $100 a week. Chaney immediately quit Universal and struck out on his own as a freelance actor.

At last free from Universal, Chaney, with a proven body of work and his unequalled makeup skills, was able to negotiate his own rate. Lon Chaney's first year after leaving Universal was a struggle, but he finally made a breakthrough when legendary Western filmmaker William S. Hart cast him in 1918's Riddle Gwane. Starring opposite Hart as a dastardly cattle rustler, he received high praise for the role, catching the eye of moviegoers and critics alike.

The year after his star-making turn in Riddle Gwane, Chaney appeared in a role that would truly showcase his talents. Based on a 1914 play, The Miracle Man features Chaney as Frog, a criminal capable of twisting his body to appear crippled. The New York Times praised the film and singled Chaney's performance out as a highlight.

The Hunchback of Notre Dame

In one of his most celebrated roles, Lon Chaney starred as a legless criminal mastermind in The Penalty. To achieve the illusion of amputation, Chaney constructed a harness which held his lower limbs bent behind him at the knees. The effect was startling. It also caused the actor considerable pain, intense lower back strain, and broken blood vessels.

The tortures of The Penalty would pale to the extremes to which Chaney would go to for 1923's The Hunchback of Notre Dame. As Quasimodo, the grotesquely deformed bell ringer, Chaney underwent a grueling three-hour process to apply the elaborate makeup, which included a 20-pound plaster hump attached with a leather harness which prevented him from standing erect. The hunchback's lumpy facial structure was created using layers of cotton and collodion. An eye wart constructed with adhesive tape and nose putty and cut down cigar holders inserted in his nostrils completed the disturbing look.

For decades, Hollywood lore has maintained that The Hunchback of Notre Dame was the brainchild of producer Irving Thalberg. However, as revealed by biographer Michael F. Blake, Chaney's stake in the epic production was far more than originally assumed. Chaney had optioned the rights to Victor Hugo's novel and had been trying to secure funding long before the project wound up at Universal. As owner of the property, Chaney was, in essence, an uncredited producer with a great deal of creative control over the film, which more than justified his hard-won salary of $2,500 per week.

The Phantom of the Opera

In 1925, Lon Chaney starred in the role that would cement his reputation as one cinema's first masters of horror. Directed by Rupert Julian, The Phantom of the Opera, based on Gaston Leroux's 1910 novel, stars Chaney as Erik, a disfigured genius who haunts the Paris Opera House. A big-budget spectacle rivaling 1923's The Hunchback of Notre Dame, the film featured Chaney's most memorable creation.

Hewing closely to Leroux's description, Chaney's Phantom is cadaverous and ghastly, with hollow eyes, ruined nose, and a mouth pulled into a skull-like rictus. To create Erik's deathly appearance, Chaney employed a combination of techniques, including traditional highlighting and shading with greasepaint and the cotton and collodion method he used to sculpt Quasimodo's features in The Hunchback of Notre Dame. How Chaney achieved the effect of the Phantom's hideously upturned nose remains a point of contention among film scholars. However, the modern consensus, backed by the account of cinematographer Charles Van Enger as cited by author David J. Skal in his book The Monster Show, is that the actor used a contoured wire appliance concealed by putty and makeup to lift and flare his nostrils.

Universal kept Chaney's horrifying new creation under wraps, barring the release of photographs of the actor in makeup until the film's premiere. The revelation of the Phantom in the film's famous unmasking scene proved a shock to contemporary audiences. As recounted by Nige Burton of Classic-Monsters.com, Erik's gruesome visage caused "women to scream and strong men to faint."

Lon Chaney suffered for his art

In his pursuit of creating realistic characters for the screen, Chaney employed painful techniques to warp and alter his physical features. Among the most radical examples is the harness he built to create the appearance of double amputation in The Penalty. According to LonChaney.com, the official website of the Chaney estate, the harness used in the film bound the actor's legs and feet tightly behind him. Only able to wear the apparatus for short periods, Chaney suffered broken blood vessels and required frequent massaging of his legs between takes. Other examples of injuries Chaney sustained for his art include the permanent partial loss of vision in his right eye due to the putty and adhesive tape wart he wore as Quaisomodo and bleeding caused by The Phantom of the Opera's wire-frame nasal appliance.

The lengths to which Chaney would go for characterizations of deformity and mutilation, while often painful, have also been largely exaggerated over the years. One famous example is the long-held assertion that the hump he wore for The Hunchback of Notre Dame was a 70-pound piece of solid rubber. In fact, the hump was constructed of much lighter plaster and was closer to 20 pounds.

In a 1991 interview with Patsy Ruth Miller, The Hunchback of Notre Dame's Esmerelda, the actress conjectured that pain was part of Chaney's process. "I felt that he almost relished that pain," Miller said. "...It gave him that feeling he wanted to have of a tortured creature."

A Hollywood phenomenon's private life

Lon Chaney's ability to radically transform himself for any role no matter how bizarre or grotesque made him a household name. Ironically, as one of the most popular movie stars of the 1920s, the Man of a Thousand Faces was notoriously reclusive. Claiming that "between pictures, there is no Lon Chaney," the actor did not attend premieres and only rarely gave interviews. "Actors should pay more attention to their work and less attention to their fan mail," Chaney once said.

Still, Lon Chaney knew the value of maintaining his myth. As recounted in a profile for PBS' American Masters, Chaney was once caught placing fallen baby birds back in their nest. He begged a witness to this act of kindness to keep quiet, explaining, "I will never hear the end of it. Everyone thinks I am so hard-boiled!"

Lon Chaney's virtual anonymity also became part of his mystique. Genre historian David J. Skal explains in his book The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror that a popular myth of the era proposed that Chaney used his natural appearance as a disguise. The famed actor could be anywhere, perhaps standing right beside you, and you'd never know it. Conversely, he might also pop up as something not human at all. A popular joke of the 1920s, originally attributed to director Marshall Neilan as a lighthearted admonition to a studio workman, was a warning to avoid stepping on spiders, lizards, and other creepy crawlers because they "might be Lon Chaney."

Cancer killed Lon Chaney at the age of 47

While shooting the railroad melodrama Thunder on location in frigid Green Bay, Wisconsin, in March 1929, Lon Chaney caught a severe cold. Despite his sickness, Chaney, a consummate professional, continued to work. His sickness progressed into a case of walking pneumonia. Upon returning to California, Chaney developed a high fever. Confined to his bed under doctor's orders, Chaney nevertheless quickly returned to work on the film.

Although Chaney was well enough to complete Thunder, his bout with pneumonia left him weakened. On July 25, 1929, Universal suspended Chaney's contract and pay (which had recently been increased to $3,750 a week) pending his recovery. Complaining of a cough and throat irritation, Chaney consulted a physician about a tonsillectomy, hoping that the procedure might relieve his chronic symptoms.

Unfortunately, Chaney's illness was far more serious than a simple case of tonsillitis. Diagnosed with bronchial cancer likely caused by years of heavy smoking, Chaney remained well enough to complete his only talking picture, a remake of his 1925 film The Unholy Three. According to Chaney biographer Michael F. Blake, the actor suffered a series pulmonary hemorrhages shortly after the film's premiere. After slipping into a coma, Lon Chaney died of a hemorrhage in his throat on August 26, 1930. He was 47 years old.

Creighton Chaney followed in his father's footsteps

Lon Chaney actively discouraged his son Creighton from pursuing a career in entertainment, and for a time, the younger Chaney adhered to those wishes and attended business college. In 1926, according to LonChaney.com, he married first wife Dorothy Hinckley and went to work for his father-in-law as secretary-treasurer of the General Water Heater Company.

Upon his father's passing, Chaney Jr. decided to change careers. Following in his father's footsteps, he became an actor. Struggling in bit parts for years, his fortunes changed when Chaney reluctantly adopted his father's name. With the added marquee value of the name "Lon Chaney Jr.," the young actor at last saw a degree of success.

In 1939, Chaney appeared in his first major role in Of Mice and Men. However, he would find his greatest fame as reluctant werewolf Lawrence Talbot in Universal's 1941 horror film The Wolf Man, kicking off a long career in the studio's beloved monster films.

Lon Chaney starred in the most famous lost film of all time

Shot on volatile silver nitrate stock, many films of the silent era, including the bulk of Lon Chaney's output, have been lost to the ravages of time. Among Chaney's missing films is one picture that is arguably the most famous lost film of all time. London After Midnight, directed by Tod Browning, stars Lon Chaney in a dual role as a Scotland Yard inspector and a sinister stranger in a top hat presumed to be a vampire. More of a mystery film than a shocker, the 1927 picture nonetheless features one of the most indelible images in the history of horror in Chaney's razor-toothed Man in the Beaver Hat.

Sadly, the last surviving print of the film was destroyed in a vault fire in the mid-1960s, according to The Hollywood Revue. A subject of endless controversy, rumors of existing prints lost under alternate titles or locked away in private collections are a constant source of debate among horror fans and cinema aficionados. Nevertheless, film historians hold out hope that another print will one day be discovered.

Lon Chaney's legacy

Nearly a century after his death, Lon Chaney's influence resonates in the work of the greatest makeup artists and character actors of all time. According to Academy Award-winning makeup artist Rick Baker, the impetus for his career choice hinged on an image of Lon Chaney. "My introduction to Lon Chaney came about because of Famous Monsters of Filmland Magazine," Baker told Turner Classic Movies. "The issue I saw had Chaney on the cover. When I found that magazine, I thought it was a gift from the gods. I became fascinated by his face. I learned how to make scary faces from looking at Lon Chaney."

Actor Doug Jones, best known for playing creatures in Guillermo del Toro's films Pan's Labyrinth and The Shape of Water calls Lon Chaney "the grandfather" of his profession. "I am fascinated by [Lon Chaney]. I am mesmerised by him," Jones says. "I revere him. I almost worship the man. Lon Chaney was a genius. Period. The end."