The Tragic Real-Life Story Of Fannie Lou Hamer

Fannie Lou Hamer was a force to be reckoned with. After working as a sharecropper for most of her life, once she learned of her constitutional right to vote, she never stopped working for equal voting rights for all.

Hamer's life was filled with hardships. When her parents earned enough money to purchase their own livestock, their animals were poisoned by white people in the community. A minor surgery turned into a forced sterilization. After an arrest for attempting to integrate lunch counters at bus stations on interstate routes, an act that was legal "given the ICC 1961 ban on segregated interstate travel facilities," Hamer was beaten within an inch of her life and suffered from lifelong health problems as a result of the beatings.

But despite everything she faced, Hamer kept fighting until her final days. And she did so with a passion. She'd always start singing "whenever times seemed most dire," whether it was as she was being arrested, in a jail cell, or at the DNC. A visit to Guinea inspired the notion of the anti-colonial struggle that she was engaged in, and Hamer described the trip as "one of the proudest moments of my life."

All her life, Hamer said she was "sick and tired of being sick and tired." One can only hope that she's found the rest she deserves. This is the tragic real-life story of Fannie Lou Hamer.

Fannie Lou Hamer was the 20th child in her family

Born on October 6, 1917, in Montgomery County, Mississippi, Fannie Lou Hamer, née Townsend, was the 20th and youngest child of Lou Ella and James Townsend. Both Lou Ella and James worked as sharecroppers their entire lives, in addition to picking up work as a domestic servant and a Baptist preacher/bootlegger, respectively.

According to For Freedom's Sake: The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer by Chana Kai Lee, when Hamer was two years old, her family relocated to Sunflower County to work on E.W. Brandon's Ruleville plantation. A bout of polio left her with a limp from the age of five, but when Hamer was six, she joined her family working on the plantation.

Hamer was essentially tricked into picking cotton as a child by the plantation owner, who offered the hungry child food if she picked 30 pounds of cotton in a week. The six-year-old Hamer never thought that she'd be expected to work every day, with no more food as a reward and with the barest pay. At the age of 13, Hamer was picking as much as 400 pounds of cotton in a day and receiving $1 for her work.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, Hamer was eight years old in 1925 when she saw Joe Pullam, a local sharecropper, lynched. In an interview with Jack O'Dell in 1965, Hamer stated, "I remember that until this day and I won't forget it."

Marriage to Pap

Fannie Lou Hamer's parents tried hard to keep their children in school, but school "lasted only four months out of the year — December through March," and they often didn't have clothes to wear. But when Hamer was able to attend school, she loved it and heeded her mother's advice: "learn to read because 'when you read, you know — and you can help yourself and others.'" Unfortunately, Hamer dropped out at the age of 12 to help her family make money in order to survive.

In 1944, Fannie Lou married Perry "Pap" Hamer, a local tractor driver who worked on W.D. Marlow's plantation. (Note: Some sources name him as "B.D. Marlowe.") According to the National Women's History Museum, Hamer joined Pap on Marlow's plantation in Ruleville until 1962.

Since Hamer had learned how to read and write during her brief time in school, she also worked as a timekeeper on the plantation, which involved maintaining the records of bales picked, pay due, and working hours. This job ended up giving her an insight into how the owners "used deliberate miscalculations and various devices to cheat sharecroppers who come to 'settle up' at the end of the season."

This injustice incited Hamer to rebel, and she started bringing her own "weighted instrument" to the scales so that sharecroppers could get their fair share. Later in her life, Hamer said, "I didn't know what to do and all I could do is rebel in the only way I could rebel."

Forced sterilization

In 1961, Fannie Lou Hamer underwent surgery to remove a small cyst in her stomach, only to find upon waking that she'd also been given a hysterectomy without her consent. According to PBS, this type of forced sterilization was so common at the time that it became referred to as a "Mississippi appendectomy," a term coined by Hamer herself. On June 8, 1964, Hamer testified before a panel in Washington, DC, that at the North Sunflower County Hospital, "six out of the ten Negro women that go to the hospital are sterilized with the tubes tied."

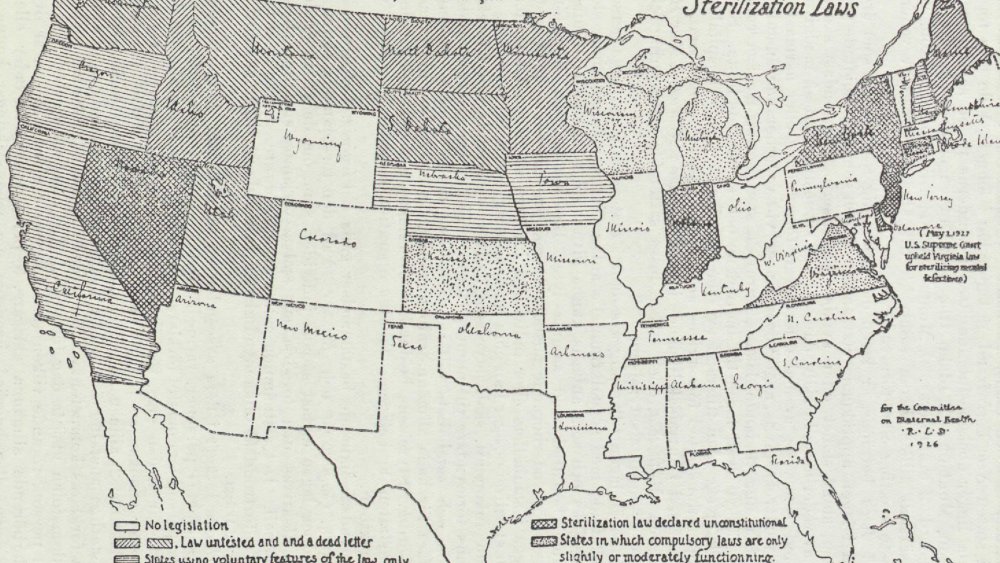

Forced sterilizations have a dark history and an equally dark present in the United States. Indiana passed the first forced sterilization law in 1907, and while they hit their peak in the 1930s and 1940s, targeting those deemed to be "criminals" and "unfit," by the 1950s, sterilization laws started targeting welfare recipients as well.

Forced sterilizations were also frequently racially motivated. This became abundantly clear when Mississippi proposed a bill that would make it a felony for a parent on welfare to have more than one child, in which jail time could be avoided if the parent "consented" to sterilization. Mississippi representative Stone Banefield is even said to have forecasted that "when the cutting starts, they [Black people] will head for Chicago." Despite sterilization being taken out of the bill in its final form, that didn't stop Hamer and countless other women from being illegally sterilized without their consent.

The beginning of Fannie Lou Hamer's civil rights activism

In August 1962, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee came to Ruleville, Mississippi, and after learning of her constitutional right to vote, Fannie Lou Hamer and 17 others volunteered to go register the following Friday, August 31, 1962.

That day, the group went to the courthouse in Indianola, Mississippi, to register to vote. According to PBS, most of the group was blocked from even attempting to register. Only Hamer and one other man were allowed to fill out an application and take a literacy test. At the time, literacy tests were purposefully designed to keep Black people from voting, and when Hamer was asked to explain de facto laws, she later recalled that, "I knowed as much about a facto law as a horse knows about Christmas Day." After failing the literacy tests, the group was denied the right to register to vote.

On their way back to Ruleville, their bus was stopped by police and fined $100 for being "too yellow." After the passengers gathered together all the money they had, the police let them go on their way. But upon returning to Marlow's plantation, Hamer found that Marlow was aware of her attempt to register to vote, and he demanded that she withdraw her application because "we're not ready for that in the State of Mississippi." Hamer refused, snapping back, "I didn't go down there to register for you. I went down to register for myself," and Marlow promptly threw her off the plantation.

Realizing that registering to vote isn't enough

On January 10, 1963, Hamer was finally able to pass the literacy test. According to The Nation, after her second attempt on December 4, she'd told the registrar that, "You'll see me every 30 days till I pass," and the following month, she found out that she'd passed. But despite now being registered to vote, she discovered that she still wasn't allowed to vote because she didn't have any poll-tax receipts.

In the United States, poll taxes were a required payment as a prerequisite to voting, and although many tried to justify them as a "revenue raiser," after people of all races were given the right to vote in 1870, states clamored to ensure that people of color couldn't exercise that right. The Tuscaloosa (Alabama) News published an editorial on November 3, 1939, that expressed those desires plainly: "This newspaper believes in white supremacy, and it believes that the poll tax is one of the essentials for the preservation of white supremacy."

In 1963, when Hamer was attempting to vote, Mississippi still had poll taxes on the books, even though the House had passed the 24th Amendment, which outlawed poll taxes for federal elections, the previous year. The Amendment wouldn't become part of the Constitution until 1964, but to this day, eight states, including Mississippi, still haven't ratified the amendment.

Assault by the police

While Pap worked to pay off their sharecropping debt at the Marlow plantation and joined his family in the fall of 1962, Hamer continued working with the SNCC toward voter registration and desegregation.

On June 9, 1963, Hamer and nine other activists were returning on a bus from a voter registration and civic education training session in Charleston, South Carolina. The activists had tried to integrate lunch counters at the various bus stations along their way home, and their protests had enraged their bus driver. According to Fannie Lou Hamer: America's Freedom Fighting Woman by Maegan Parker Brooks, the driver began using the phone at every stop, and the activists correctly suspected that he was reporting their protests to the Mississippi police.

In Winona, Mississippi, police arrested at least six of the activists, even those who'd remained on the bus, and took them to jail. Hamer and her fellow activists weren't released from jail until June 12, and in those three days, Hamer sustained such beatings that she suffered from lifelong damage to her kidneys, eyes, and legs. In addition to beating the activists themselves, police also commanded the other Black people who were also imprisoned in the jail at the time to beat the activists as well. Police handed them leather blackjacks and said, "If you don't, you know what I'll do to you."

While there was a brief trial, the police were cleared for their actions.

The Mississippi Freedom Democrtic Party

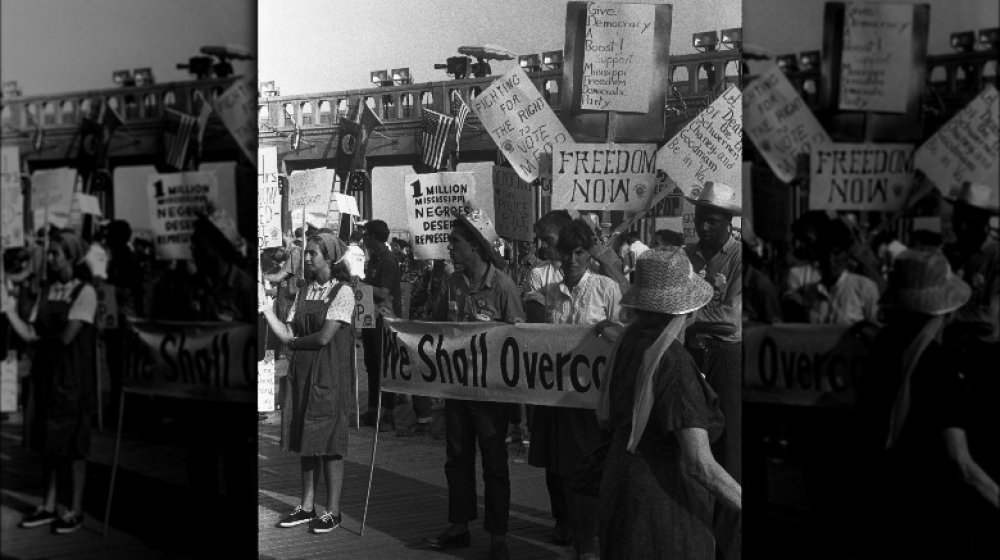

After several failed attempts to work with the pro-segregation and all-white Mississippi Democratic Party, Hamer co-founded the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party with Ella Baker and Bob Moses. According to Fannie Lou Hamer by Maegan Parker Brooks, the MFDP gathered an interracial delegation "to challenge the all-white delegation at the 1964 DNC." Hamer was also selected to be vice president of this delegation.

Before going to the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, Hamer had received a death threat. When she called the police, she was told, "You know you don't look to us for help." On August 22, 1964, Hamer testified before the credentials committee at the Democratic National Convention. She began her testimony by stating her full name and address, standing up to every white supremacist, for this opening "did more than establish her credibility as a resident of Mississippi, it defiantly directed the Klan and the Citizens' Councils right to her front door."

According to The Washington Post, President Johnson was terrified, since he needed the Southern Democrats in order to win re-election. He'd initially sent people to persuade Hamer not to testify, but she would not be intimidated. So when that didn't work, Johnson called an abrupt news conference to steer the live broadcast away from Hamer. Unfortunately, his plan backfired. Hamer's testimony was so striking that many evening news programs showed it, which led to the speech reaching a much greater audience than it would've during its original broadcast time.

A farcical compromise is rejected

Unfortunately, as a result of pressure from both President Johnson and Hubert Humphrey, the Credentials Committee refused to accept the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. According to Fannie Lou Hamer by Maegan Parker Brooks, Humphrey even tried to convince Hamer to drop her demands for a vote, "his round eyes filled with what she later described as 'crocodile tears,'" by claiming that he wouldn't be nominated for vice president. Hamer responded, "do you mean to tell me that your position is more important to you than 400,000 Black people's lives?" and was shocked at his utter indifference.

Democratic officials offered a farcical compromise to the MFDP: They'd be allowed two delegates, but they could neither sit in the Mississippi section, nor would they be able to cast votes. But neither one of those seats were allowed to go to Hamer, since President Johnson had said that "he will not let that illiterate woman speak on the floor of the Democratic convention."

The MFDP voted unanimously to reject the administration's compromise. In Hamer's words, "We didn't come all this way for no two seats." They returned to Mississippi.

Fannie Lou Hamer runs for political office

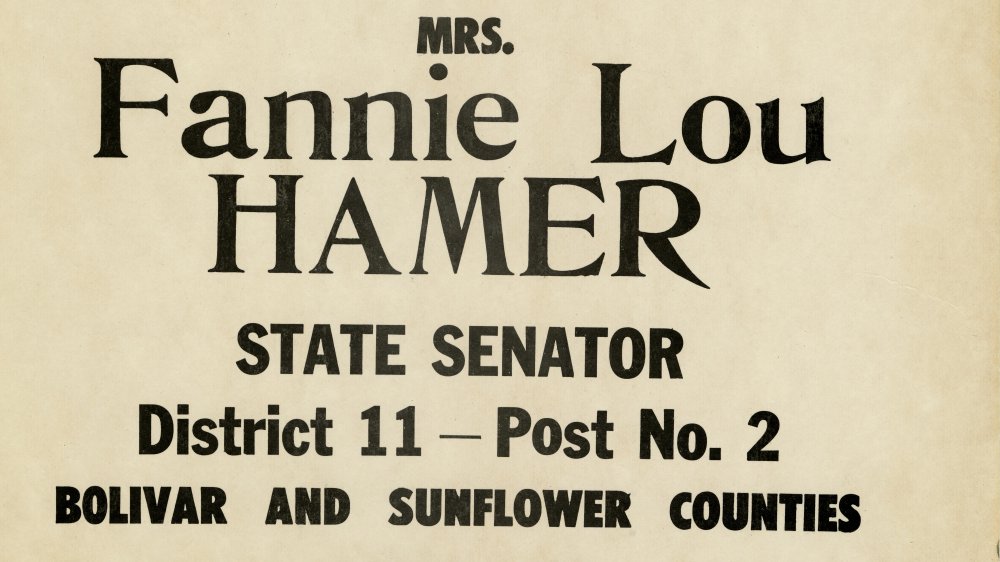

In 1964, Hamer also ran unsuccessfully for Congress. According to an interview with Jack O'Dell, Hamer recalled that it was harder for her to pass the literacy test in order to register to vote than it was for her to qualify to run for Congress. And despite being barred from the ballot, the MFDP gave out "Freedom Ballots" that included candidates of all races.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, after her first bid was unsuccessful, Hamer ran for office two more times, in 1967 and 1971. Unfortunately, her 1967 run was disqualified because Hamer had voted in the August Democratic primary, and she lost to the incumbent in 1971.

According to Fannie Lou Hamer by Maegan Parker Brooks, despite being incredibly critical of establishment politics, Hamer worked to affect the system from both the outside and the inside. Her repeated runs for office "suggested both a deep-seated faith in the democratic process and a recognition that holding political office could help expand the radical programs for economic justice she had created." Once the Democratic Party required equal representation for state delegations in 1968, Hamer became part of the Mississippi delegation for the National Democratic Party Convention. During this time, she was a passionate critic of the Vietnam war.

Pushing for economic equality

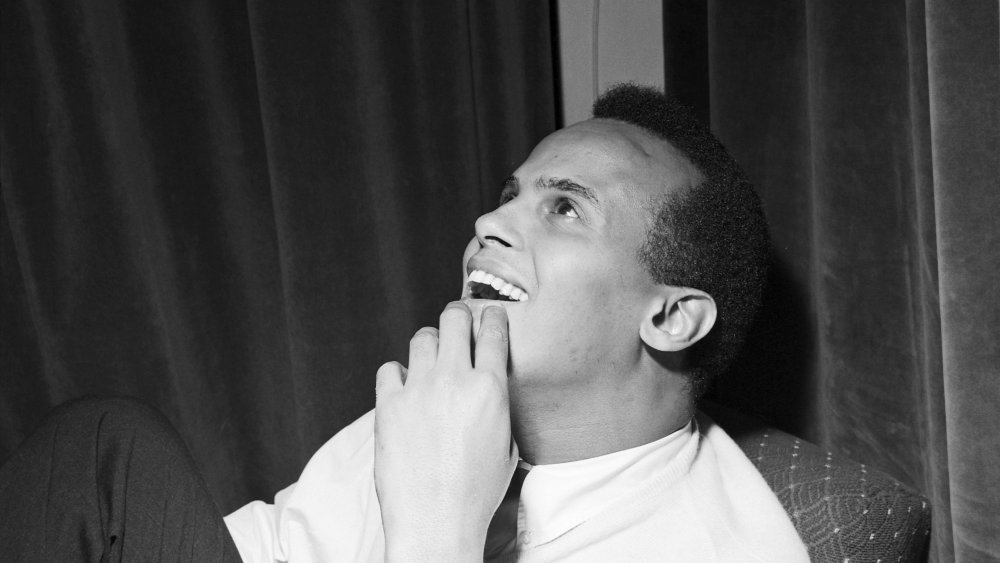

Seeing that not much progress was being made on the political front, Fannie Lou Hamer turned most of her attention toward economic justice as a way to fight for racial equality. According to the SNCC, in 1969, Hamer founded the Freedom Farm Cooperative in order to provide Black people with land that they could own and farm collectively. With the help of donors such as the Measure for Measure organization and Harry Belafonte (pictured above), by 1970, the co-op had amassed 680 acres for cultivation. Membership for the co-op was $1 a month, and even though only 30 families could afford the dues, those who couldn't pay weren't excluded. Roughly an additional 1,500 families were also part of the Freedom Farm Cooperative in name.

In 1970, the collective also started a "pig bank" for impoverished families. With help from the National Council of Negro Women, the collective purchased five male pigs and 35 female pigs, and over the next three years, thousands of pigs made their way to Black families. Hamer especially loved the pig bank, stating that "I wouldn't take nothing for our golden pigs."

Unfortunately, without institutional backing or resources, the Freedom Farm Collective only lasted until the mid-1970s. But at its height, it was one of the largest employers in Sunflower County.

Providing assistance with lawsuits

Even after the Voting Rights Act was finally passed in 1965, Fannie Lou Hamer continued to focus on equal voting rights. Despite the federal protections that the Voting Rights Act claimed to guarantee, white people continued to try to prevent Black people from registering and voting. And unfortunately, racially motivated voter suppression continues even up toward the 2020 election.

According to the Center for Constitutional Rights, Hamer was actually partly responsible for the Voting Rights Act's passage thanks to her civil rights case Hamer v. Campbell (1965). Brought against the circuit clerk of Mississippi for restricting Black people's right to register and vote, Hamer's victory in court even allowed the elections to be overturned due to their discriminatory practices.

According to PBS, Hamer also organized plaintiffs for a class-action lawsuit regarding school desegregation in Sunflower County in 1970. This suit resulted in the district court ordering the county to merge its segregated schools into a single public school system, and the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit upheld the district court's decision in United States v. Sunflower County School District.

I'm sick and tired of being sick and tired.

Fannie Lou Hamer's health suffered during her final years, and in 1976, she was diagnosed with breast cancer and underwent a radical mastectomy. She continued her civil rights work as long as she could, but as her health worsened, fundraising and public speaking became more and more difficult.

According to BlackPast, Hamer died on March 14, 1977, her life cut tragically short at the age of 59. Hundreds of people came to pay their respects, but some disparaged the media circus that transpired. According to Fannie Lou Hamer: The Life of a Civil Rights Icon by Earnest N. Bracey, some people in the SNCC-COFO thought that the funeral turned into "a media event with dignitaries from around the country competing with one another to be seen on camera, pushing her neighbors into the background. It seemed the perfect contradiction of the values [Hamer] tried to live by." It ended up being one of the most publicized funerals in the history of Mississippi.

Hamer was buried at the Freedom Farm Cooperative, and her gravestone bears her oft-repeated motto, "I'm sick and tired of being sick and tired."