False Things You Believe About America's Founding Fathers

The names of the Founding Fathers are invoked a lot, especially when talking about the state of the country these days. How many social media posts lament political decisions of one sort or another, then make it clear that this isn't what America's Founding Fathers had in mind when they wrote the Declaration of Independence or signed the Constitution?

But how much do you really know about our Founding Fathers? We're taught a lot in school, and it's often stories like George Washington chopping down the cherry tree, then admitting it to his father because he couldn't tell a lie. Just the fact that he didn't get in trouble at all should be a hint that yes, it's a total myth. Mount Vernon says it was made up by Mason Locke Weems, one of the first people to write a biography about Washington. The idea was that he wanted to write a book that put the spotlight right on Washington's personal virtues, and in order to do that, he had to make some stuff up. And that's not the only tall tale we've been told.

It turns out there's quite a few things everyone knows about the Founding Fathers that just aren't true.

George Washington had wooden teeth

Everyone knows George Washington had wooden teeth, right? It's up there with the cherry tree story, and actually, it's just as false. According to William Maloney, a professor of dentistry at New York University (via Popular Science), receipts show Washington tried everything he could to keep his teeth, but only had one left by the time he was inaugurated as president for the first time. His ill-fitting dentures always caused him some serious pain, and that brings up the question of what they were made of.

Mount Vernon says that no, not a single set of his dentures had wooden teeth. They know that because for starters, wood just wasn't used. False teeth were more commonly made from lead, gold, or ivory, and here's where things get uncomfortable — they were also made with human teeth. And where did those come from?

Buried in Washington's ledgers is a disturbing entry, and it was written in May 1784. It read (via Washington Papers): "By Cash pd Negroes for 9 Teeth on Acct of Dr. Lemoire." That one notation has led historians to the conclusion that the human teeth used in his dentures — which are still a part of Mount Vernon's collection of Washington's memorabilia — were purchased from some of his slaves. Also noteworthy is that Washington's dentist had taken out newspaper ads advertising the price he was willing to pay for teeth, and noting that slave teeth weren't worth nearly as much as teeth from other sources.

Thomas Jefferson's affair with Sally Hemings was a recently discovered secret

Remember the first time you heard about the claim that Thomas Jefferson had an affair with one of his slaves? Her name, of course, was Sally Hemings, and not only did the union produce children, but it was an incredibly awkward thing to discuss about a Founding Father. While it might seem like something that only came to light recently, it isn't.

Jefferson became the third US president on February 17, 1801. In the September 1802 edition of the Richmond Recorder, journalist James Callender wrote (via the Smithsonian): "IT is well known that the man, whom it delighteth the people to honor, keeps, and for many years has kept, as his concubine, one of his own slaves. Her name is SALLY." It was a massive scandal, and Jefferson supporters who waited for an official statement denying the story just didn't get one.

It turns out that Jefferson's colleagues had known about it for years before the story even broke. Historians found letters that John Adams wrote to his sons, Charles and John Quincy. He makes very blunt reference to the knowledge that Jefferson had left his position as Washington's secretary of state and returned to his estate to, Adams wrote, have "conversations" with a certain woman he referred to as Egeria, a nymph from Roman mythology. Or, as historians believe, the woman also called "Dashing Sally." (And yes, "conversations" is slang for the old hanky-panky.)

The Founding Fathers who signed the Declaration of Independence were all men

Everyone knows that all the signatures on the Declaration of Independence were men, right? Not so fast. Granted, this is a technicality, but it's also a technicality that could have been deadly for the Declaration's only female "signer," and here's what happened.

In 1776, the Continental Congress packed up the Declaration of Independence and sent it from Philadelphia to Baltimore. Things weren't looking good, but as the tide of the American Revolution started to turn, they ordered a second printing of the Declaration. Yes, it was the second printing, but it was the first printing with the names of the signers.

The person responsible for the printing was Mary Katherine Goddard, who was one of the era's most prominent publishers (along with being Baltimore's first postmaster). The Smithsonian says that not only did she write and print some pretty inflammatory thoughts on the "savage barbarity" of the British, but when she was tasked with printing the Declaration, she included her own name at the bottom: in (via Time) the text "Baltimore, in Maryland: Printed by Mary Katherine Goddard." That was a huge deal — Georgetown law professor Randy Barnett says that had things gone sideways, Goddard would have faced prosecution as a traitor, just like the other signers.

Samuel Adams was a successful brewer

This one's a given, right? Clearly, Samuel Adams was a successful brewer, why else would he have a whole company named after him now?

Only, that's not exactly the case. Adams' father was Deacon Samuel Adams, and he was the sort of rich man who founded political parties. (Namely, the Boston Caucus.) He also owned a malt house, says the New England Historical Society, which was essentially responsible for preparing ingredients (ie., malted barley) to sell to the brewers who were doing the actual brewing.

HIs son was a different story. Adams the younger went to Harvard, then jumped around a bit career-wise. When Adams the elder died in 1748, his son inherited the family business. What happened next is one of those bits of history that's a little fuzzy at best. While some claim there's receipts and advertisements — like one in a 1751 edition of the Boston Evening Post — that suggest Adams was a brewer as well as a maltster, that's kind of irrelevant to the whole "success" part. According to History, Adams took the successful business he inherited from his father and did such a bad job running it that he was bankrupt in just a few years. The building was quite literally crumbling, his family estate was put up for sale, and he kept it by intimidating the heck out of anyone who considered buying it.

Alexander Hamilton was 100 percent anti-slavery

Of all the Founding Fathers, Alexander Hamilton was definitely anti-slavery, right? Right?

According to Harvard Law School professor and historian Annette Gordon-Reed, it's not that straightforward. In fact, she says, "He was not pro-immigrant, [...]. He was not an abolitionist. He bought and sold slaves for his in-laws, and opposing slavery was never at the forefront of his agenda. He was not a champion of the little guy, [...]. He was elitist." Gordon-Reed says the Hamilton of history definitely isn't the one that's seen on stage and in musical form. Den of Geek did a deep dive into the real Hamilton's history to find out just what got the ol' creative license treatment, and found there was a lot.

For starters yes, Hamilton wasn't fond of slavery, but at the same time he supported anti-slavery friends, he still made it a point to marry into a family reliant on slave labor. The Schuylers owned a group of slaves that worked in their Saratoga, New York mills, and Hamilton was involved in the buying, selling, and leasing of those slaves. He was also a supporter of the "Three-Fifths Compromise," and as for whether or not he owned slaves? Hamilton's grandson, Allan McLane Hamilton, had this to say in his grandfather's biography (via History): "It has been stated that Hamilton never owned a negro slave, but this is untrue. We find that in his books there are entries showing that he purchased them for himself and for others."

Benjamin Franklin wanted the national bird to be a turkey

Here's one that pops up on a regular basis: Benjamin Franklin had campaigned for the national bird to be not the bald eagle, but the turkey. Silly Franklin, what a goofball!

And no, it's not actually true. According to The Washington Post, the rumor started a good long while ago. Franklin, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson were all appointed to a committee that was tasked with developing a national seal, but the problem was that they were all lacking in artistic talent. Franklin's suggestion was — according to a letter written by Abigail Adams — Moses parting the Red Sea, and submerging the Pharaoh's chariot.

Wait, what? The turkey only came around later, after they'd settled on the bald eagle. Franklin wrote to his daughter and said that he wished it wasn't the eagle at all, calling it "a Bird of bad moral Character," and lamenting that the turkey "was a much more respectable Bird." And that's it. That's where the whole thing started. Here's a little footnote to the story, and we'll spare the gory details. Franklin definitely wasn't partial to turkeys: he conducted (pun not intended) a series of experiments in 1750 to determine just how much electricity it took to kill them.

Thomas Jefferson campaigned for separating church and state

Sometimes, history gets a little fuzzy, and the original meaning of some pretty important ideas gets lost. Take the idea of separation of church and state. That's often said to mean the government should act in such a way that's completely separate from religious influence, and that's how the Founding Fathers wanted it, right? Not quite.

In 1786, Thomas Jefferson wrote the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, and Time says that's where the whole idea came from. So far, so good — but what we say it means isn't actually what he meant when he talked about a "wall of separation" between church and state. He was actually talking about keeping the state out of the church: Americans, he thought, should be free to worship as they pleased... or not at all, and he didn't want the government to say otherwise.

Radical, right? What he never suggested is that the government should keep the church out of their affairs, and that freedom to practice religion extended to them, too. Still doubt? According to Mental Floss, when it came time for some of the Founding Fathers to submit their ideas on what the nation's new official seal should be, Jefferson's was definitely rooted in religion: he believed the seal should depict Exodus and the Israelites' freedom from slavery.

John Hancock wrote his name so the king could read it without his glasses

There's only one thing that many people know about John Hancock, and that's the fact that he wrote his name so large on the Declaration of Independence that King George III could read it without his glasses — and he boasted that the reward for his capture would be doubled.

Unfortunately, that "fact" is wrong, and there's a few reasons we know. For starters, the National Archives says there's zero evidence the British had ever issued a bounty on Hancock. Then, there's the whole thing about the king reading it without his glasses. The massive problem with that part of the tale is that no plans were ever made to send the king a copy. The signed copy, says All Things Liberty, was always meant to stay in the US. When it was printed and sent abroad, the signatures were typeset, not copied from their actual signatures.

Any rumors that Hancock signed so large because he was the first to sign and wanted to set an example for the others in the room is also false: Snopes says that in spite of the mythology of the event, the document wasn't signed in a massive gathering on the 4th of July. It was actually signed a month later, and it was seen as such an insignificant event that no one even knew the date for over a century.

George Washington was all about arming citizens

Americans love their guns: according to the American University, 2020 statistics say that 40 percent of American adults have a gun in their home, and even though the US only has about 4 percent of the world's population, it also has 40 percent of the world's civilian-owned guns. The right to bear arms is in the Constitution, and George Washington himself is often quoted as being all in favor of getting guns into civilian hands. He's usually quoted as saying things like, "Firearms stand next in importance to the Constitution itself," and "When government takes away citizens' right to bear arms it becomes citizens' duty to take away government's right to govern." Strong words for sure, but according to Mount Vernon, Washington never said or wrote either of those things.

Some of Washington's gun quotes have been sourced. The one about a nation that doesn't allow its citizens guns "because such a government has evil plans" actually came from the online magazine The American Wisdom Series. Their Pamphlet #230 purports to share Washington's thoughts on guns, but there's no citations — and no sign of the quote elsewhere.

Other sentiments have been misquoted and misinterpreted, like the one about free people being armed in order to protect their independence, from their own government, if needed. He was actually talking about being armed so the country wasn't dependent on others for military supplies — and that's a big difference.

Patrick Henry definitely said that thing about liberty or death

It's one of those quotes that everyone knows: Patrick Henry definitely said in a stirring speech, "Give me liberty, or give me death."

While this one isn't a definite "no," it is a "highly unlikely." The Constitution Center says that Henry was said to have uttered those famous words on March 23, 1775, as he was rallying his fellow countrymen to revolution. He was talking about organizing into armed militias, and by all accounts he ended the speech with a passionate plea. But here's the thing: there are no transcriptions of the speech, and "give me liberty or give me death" didn't show up anywhere until a man named William Wirt reconstructed the speech in an 1817 biography. There, he re-wrote the speech based on accounts of those who were there — almost 40 years prior at that point.

Henry, History says, was a fire-and-brimstone sort, and when he stood up to give his speech, he had nothing written down — not even notes on what he was going to say. Many historians believe his famous words were actually written by either Wirt himself as he reconstructed the speech, or by St. George Tucker, an attorney who had been at the convention Henry spoke at. Although accounts of the speech were written, those words were never recorded until Wirt.

The Founding Fathers all signed the Constitution

Signing the Constitution is one of the things that makes them Founding Fathers... right? Not exactly. Oak Hill Publishing says that there were a lot of Founding Fathers who didn't sign, for one reason or another. Some, like William Houston and Abraham Clark (both of New Jersey) and Thomas Nelson (of Virginia) left the conference early due to failing health. Virginia's George Wythe and Maryland's Thomas Stone also left early, to attend wives that had fallen ill. Others had less personal reasons.

Patrick Henry refused to sign, citing fears that it would ultimately restrict personal freedoms too much, and impose on the rights of individual states. His fellow Virginian, Edmund Randolph, initially said there weren't enough checks and balances put in place (although he got on board with it later).

The New York delegates, John Lansing and Robert Yates, stood together in opposition to it on the grounds that it created too strong a national government. Massachusetts' Caleb Strong refused to sign because he didn't agree with the idea of the Electoral College, and several — George Mason (Virginia), Richard Henry Lee (Virginia), and Elbridge Gerry (Massachusetts), all refused to sign because there was no Bill of Rights in place yet — something Randolph also supported the addition of.

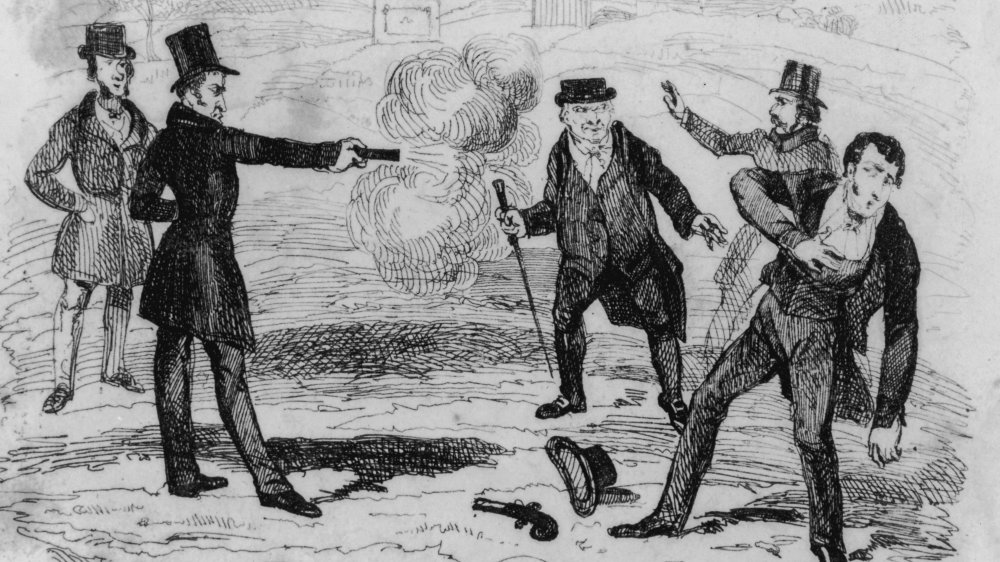

Alexander Hamilton's death-by-duel was unique

It's impossible to talk dueling without mentioning Alexander Hamilton, who was killed by life-long rival Aaron Burr in 1804. They were such bitter rivals that History says that's what the duel was about — honor. If you think Hamilton was the only Founding Father to have died in a duel, you're wrong.

In 1777, Button Gwinnett was not just a signer of the Declaration of Independence, but he was also at the head of Georgia politics. According to History, one of his major concerns was securing the border between Georgia and Florida. Gwinnett argued with a political rival named Lachlan McIntosh, not over whether or not a planned expedition would happen, but over who was going to lead it. The solution? To duel. Both men were shot, and while McIntosh recovered, Gwinnett's wound turned gangrenous and he died three days later.

Then, fast forward to 1802. The North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources says political rivals John Stanly and Richard Dobbs Spaight had spent about two years trading personal attacks through pretty much every means possible. Finally, it all came to a head on September 5 when, in front of 300 people, they faced off with flintlock pistols. Spaight — who had been North Carolina's representative at the Constitutional Convention — was hit during the fourth round of shots and died the following day.