These Nazi War Criminals Were Never Brought To Justice

World War II came to an end in 1945, and afterward, it was left to the survivors to pick up the pieces. Those who survived the horrors of the concentration camps tried to get on with life — and honor the loved ones they'd lost — while soldiers returned home and tried to cope with what they'd seen. On an international stage, another drama played out: the Nuremberg trials.

According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 199 Nazi criminals went on trial at Nuremberg. Of those, 161 were convicted, and 37 were given the death penalty.

That sounds like a lot, but it's only a very small percentage of those who spent the war years wearing an SS uniform. The SS — developed by Heinrich Himmler, and turned into a paramilitary unit responsible for some of the most horrific crimes of the war — had around 50,000 members by 1933. By the start of the war, there were around 250,000 members of the SS, and by the end? Estimates suggest the SS and the Waffen-SS had boasted a membership of up to 910,000 or more (via History).

When the Allies declared victory, some fled Germany. Others folded up their uniforms and went back to their pre-war life. Many Nazis were never brought to justice for their crimes, including these.

Josef Mengele, the Angel of Death, died free

When it comes to the most notorious of Nazis, many are familiar with Josef Mengele, the Angel of Death and the doctor of Auschwitz, who was responsible for some of the most horrific medical experiments of the war (via the BBC).

Mengele, The New York Times reports, left Germany and headed to Argentina in 1948. He got there using forged documents supplied by the Red Cross. Once he was there, he didn't even hide: the nameplate on his office door in Buenos Aires read "Dr. Josef Mengele."

What followed involves a complicated set of circumstances, tips, and priorities, but basically, the Mossad, Israel's espionage agency, didn't start chasing Mengele in earnest until 1960. That's when they were tipped off to his location by Simon Wiesenthal, and here's where things get weird. The Mossad spotted Mengele, and then, the higher-ups ordered them to drop everything and go to Egypt, where German scientists had been recruited for building missiles. This was at the same time they apprehended another top Nazi — Adolf Eichmann. Two years later, The Local says they identified him again, working in São Paulo. The Mossad chief refused to approve an operation to capture him, citing "other priorities."

Mengele was a free man when he died in 1979: he was swimming off a São Paulo beach and drowned.

The architect of the Gassing Vans

In 1941, Walter Rauff was working for the Reich Security Main Office, and what's when the Jewish Virtual Library says he started working on a new idea he'd had: remodel some of the nation's heavy trucks and turn them into mobile gas chambers. Exhaust from the vans was re-routed into airtight chambers with enough room for up to 50 people at a time.

Rauff was in Italy at the end of the war, and after spending some time hiding in a series of convents, he went on to Syria, then Ecuador, then finally on to Chile. It was there that the Jewish Virtual Library says he was finally arrested in 1962 (pictured, left), and then freed: Chile refused Germany's request to extradite him to stand trial for his crimes. A decade later, the Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal tried again to get him extradited, and again, the request was refused.

Rauff, meanwhile, settled down to work at a crab cannery at the very southern tip of South America. He was interviewed for a documentary in 1979 and died in 1984 after a heart attack. When news of his death went public, the Nazi hunter Beate Klarsfeld said (via The New York Times): "It was God that made justice. It is unfortunately that it was not German justice. But the problem is now resolved."

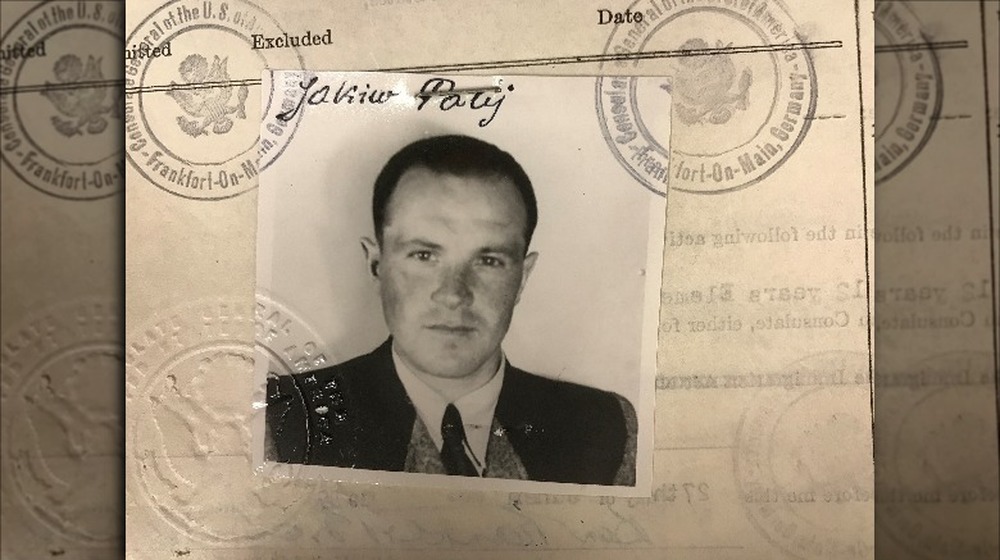

Was this man a farm worker or Trawniki guard?

In 1949, Jakiw Palij headed to the US. The story he told was that he had spent the war years laboring on his father's farm, but when the US Holocaust Memorial Museum started looking into his story, NPR says they found something very different. Palij had served as an armed guard at Trawniki, a camp originally built as a holding center for Soviet POWs, which later became a training camp for guards who served at killing centers and forced labor camps across the Reich.

Palij — who had been given US citizenship in 1957 — settled in Queens, and according to the BBC, it wasn't until 2003 that a judge revoked his citizenship. He was ordered to leave the country in 2004, but there was a huge problem: no one wanted to take him. So, he stayed in Queens. His house was the site of frequent protests, but since the courts ruled there wasn't enough evidence to find him personally responsible for deaths — something he'd always denied — there just wasn't much they could do.

That same lack of evidence surfaced when Germany finally agreed to take him back in 2018. The following year, it was announced that Palij had died. He was 95 years old and was never charged with any crime.

From Nazi war criminal to beekeeper

A strange bit of international affairs erupted — along with a ton of controversy — in 2015. According to The New York Times, it started when Moscow went to the Canadian government and demanded the extradition of Vladimir Katriuk. Katriuk, they said, had been a part of a Ukrainian battalion of soldiers who — under SS orders — participated in the murder of innocent civilians. The Guardian says that research conducted in 2012 connected Katriuk to a massacre in March 1943, where witnesses testified he manned a machine gun and killed anyone who attempted to flee from a barn that had been set on fire. (Katriuk's attorney, meanwhile, has said that while he was in the military, his role had been mostly guarding livestock.)

Katriuk eventually deserted from the battalion, headed to France, joined first the Free French and then the French Foreign Legion, then deserted and headed to Canada when he found out he was about to be deployed. He entered under his brother-in-law's name (because he was a Foreign Legion defector, he said), and settled down to raise bees and sell honey.

Attempts made to get him extradited were started in the early 1990s, and it wasn't until 2007 that — citing his age — Canada declined to revoke his citizenship. After Canada refused Moscow's 2015 extradition request (saying they weren't going to acknowledge any control Moscow might claim over Ukrainian affairs), it was announced just two weeks later that he'd died after suffering a stroke.

From violence [...] against women and children to tea and cookies

British historian Guy Walters was writing a book when he tracked down Erna Wallisch. He found her in 2007, and the then-85-year-old was sitting at number seven on the Simon Wiesenthal Centre's list of most-wanted Nazi war criminals. According to The Telegraph, she was hiding almost in plain sight: she was living in a little apartment along the Danube right in Vienna, her name clearly labeling the doorbell for her home.

When confronted, she refused to comment. Neighbors also stood by her, with one saying, "It's all in the past and should be forgotten. People should learn to forgive."

Testimonies compiled by survivors at the concentration camps where she was a guard — first Ravensbruck, then Majdanek — say there's too much to forgive. Originally Erna Pfannenstiel, she joined the Nazi party as a teenager and became a guard at Ravensbruck not long after. In 1944, she married another Nazi guard, Georg Wallisch, and camp survivors say she was unmistakable — those like Jadwiga Landowska say that the image of the pregnant Nazi guard beating women and children to death was burned into their memory: "The sweating, breathless face of that monster was something I will never forget."

In spite of evidence and testimonies, Austria's Justice Ministry refused to prosecute her, citing the expiration of the statute of limitations. According to The New York Times, she died in 2008.

The Butcher of Riga was never brought to justice

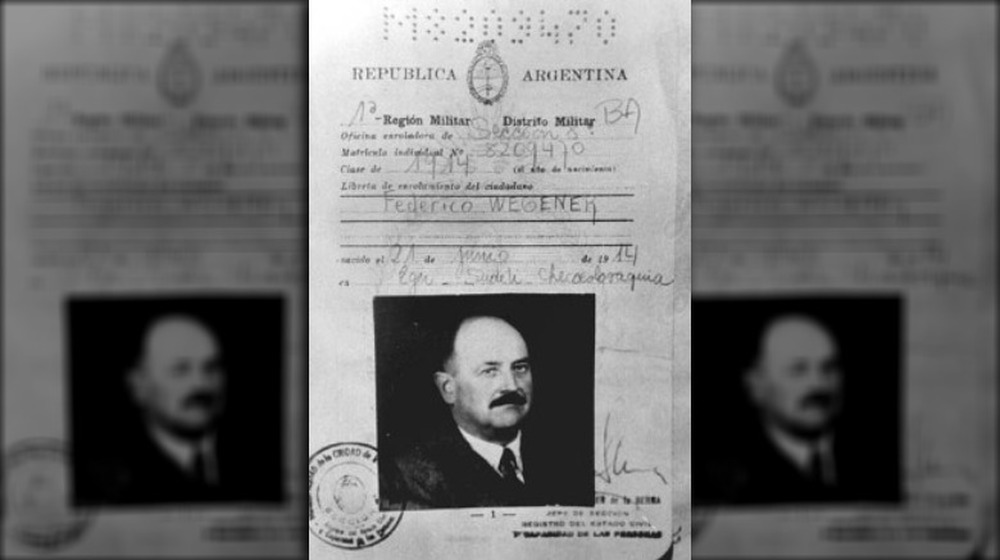

Eduard Roschmann was the commandant of the Riga ghetto in the early 1940s, and according to the Associated Press, he had a lot of blood on his hands. During the war, he was an SS captain and had been responsible for the murder of tens of thousands of Jews being held in Latvian forced labor camps. After the war? He skedaddled off to Argentina, like many Nazi war criminals did.

It's hard to overstate just how important Argentina was when it came to sheltering Nazi fugitives. DW says that many fled along what were known as the ratlines: a massive, interconnected network of Nazi sympathizers who helped wanted men get out of Germany and on their way to the country that Simon Wiesenthal called the Nazi's "Cape of Last Hope."

Roschmann, ZMAN says, fled to South America in 1948. It wasn't until 1977 that The New York Times reported that Argentina had refused West Germany's request to extradite him, which came alongside a request to arrest him and keep him from fleeing again, should he find out that authorities were after him. Argentina refused that, too, and Roschmann did, in fact, flee to Paraguay. He was dead three weeks later: officially of a heart attack, but there was a rumor that someone had taken matters into their own hands, and poisoned him.

The mysterious end of Nazi war criminal Dr. Death

Dr. Aribert Heim earned the moniker Dr. Death for a shockingly long list of reasons, mostly involving the experiments he conducted on those being held at the Mauthausen concentration camp. That's where he performed operations without the use of anesthesia and injected various solutions into the hearts of prisoners to see who would die the fastest (via the Jewish Virtual Library). And yes, he absolutely got away.

In 1945, Heim was captured, held as a POW, and then released — his file didn't include any information about his time as a doctor in Mauthausen. After his release, he headed back to Germany with his wife and sons, where he set up a gynecology practice. It wasn't until 1962 that he got wind of the fact that someone was out to put him on trial for his crimes, and he led them on a wild chase through Latin America, Europe, and finally into Egypt, where he ultimately settled, converted to Islam, and changed his name to Tarek Hussein Farid.

According to The New York Times, none of the new friends he'd made in Cairo had any idea that he was a wanted Nazi war criminal, although they did know there was something fishy about him. He lived there until his death in 1992 — from rectal cancer — which the BBC says was only confirmed in 2012.

The SS captain who sent around 130,000 to their deaths

Adolf Eichmann was one of the architects behind the plan dubbed the "Final Solution," and according to the Times of Israel, he was hanged in 1962. The man he had called his right hand — Alois Brunner — escaped.

He left Germany in 1953 and headed to Egypt under a false name. He later moved to Syria, where he consulted with Syrian police — and shared tactics developed by the Nazis for interrogation. Syria repeatedly denied he was there.

Brunner had been tried, convicted, and sentenced to death in absentia in 1954, as the head of the Drancy internment camp, for the deaths of around 130,000 people, and being the guy dispatched to areas where the higher-ups believed the killing wasn't happening fast enough (via the BBC). After the death sentence was abolished in France in 1981, the sentence was changed to life imprisonment — but still, he evaded capture.

After two assassination attempts, the Syrian government he had been consulting with had moved him to a basement room for "security reasons." Later, a former member of the Syrian secret service known only as "Omar" revealed his fate: "Once he was in the room, the door was closed and never opened again." That was in the 1990s, and one of his guards later revealed that he "suffered and cried a lot in his final years, everyone heard him." The Simon Wiesenthal Center has officially declared his death as taking place in Damascus in 2010.

The translator for the killing squads got away with it

With each year and every decade that passes, there are fewer and fewer chances to bring Nazi war criminals to justice in a court of law — and it's getting harder and harder for courts to agree to not only deporting ex-Nazis who have been living outside of Germany but to putting them on trial.

That's at the heart of the case of Helmut Oberlander. In 2020, the then 95-year-old man — who had once worked as a translator for the Nazi's death squads — was still struggling in a 25-year-long battle over whether or not Canada should deport him. By then, though, his legal team argued (via National Post) that his physical and mental capacities were so greatly diminished that he wasn't able to understand what was going on.

The CBC says that Oberlander had always been adamant that he had been forcibly conscripted when he was just a teenager. He has never been charged with a crime, he isn't accused of killing anyone, and has been living in Canada since 1954. Those who believe he should still face justice — no matter how old he is — point out that he "was a member of a Nazi killing unit responsible for the murder of tens of thousands of Jews."

The commander they called Wolf escaped

Michael Karkoc was living in Minnesota when he died in 2020. He was 100 years old, says the New York Times, and he was buried beside his wife. She had predeceased him by 2 years, and at the time, his son was still fighting to clear his name.

Here's where things get complicated. Karkoc was first identified as a former Nazi — specifically, as a commander in the Ukrainian Self-Defense Legion, which was overseen by the SS — by a reporter for the Associated Press. Along with his name, the reporter had uncovered a legion of documents, including Karkoc's own memoir.

He published that memoir in 1995 under both his real name and the nickname he'd gone by in the service: Wolf. In it, he talks about being a part of a right-wing political party that makes a deal with the Germans: if the Nazis stop killing innocent Ukrainians, their organization will help them fight the Soviets.

Except the testimonies of others don't exactly stop there. His name was also mentioned in witness statements as the commander of a unit responsible for the massacre of the entire village of Chlaniow. The original documents, The Guardian says, are supported by more uncovered testimony that claims the "Wolf" was the one giving the orders.

The investigation by the AP sparked interest in the case, and in 2017, Poland announced they would seek extradition. Karkoc — then 98 years old — died before that could happen.

Death or prison for this Nazi war criminal

By the time Reinhold Hanning was put on trial, he was in his 90s. His health and age meant that the trial could only go on for four hours each week, spread out over two days. According to Time, when he entered the courtroom it was in a wheelchair — and it was hard for anyone to see him as the Auschwitz guard who had been involved with the murder of more than 170,000 people.

Hanning, the indictment said, was a member of a company of guards who were tasked with monitoring prisoners as they were directed either to the work camps or the gas chambers. He said (in a statement via his lawyer), "Nobody talked to us about it in the first days there, but if someone, like me, was there for a long time, then one learned what was going on. People were shot, gassed, and burned. I could see how corpses were taken back and forth or moved out."

He had been at Auschwitz from 1942 to 1944, and according to the BBC, he was ultimately put on trial and convicted in 2016. Where was he in the meantime? He had been running a dairy shop. In spite of his conviction, this Nazi war criminal never served jail time: he died while waiting for the appeals in his case to start.

Red tape and bureaucracy meant a life of freedom for a Danish SS officer

Soren Kam's list of offenses is long: according to The Washington Post, it went back to 1943, when he killed an anti-Nazi newspaper editor. The crime happened in Denmark, and Kam not only escaped Denmark for Germany, but was given German citizenship in 1956. That's important — it allowed him to stay safely in Germany, away from Danish justice.

He was also linked to the theft of a registry of Jewish citizens, their ultimate deportation to concentration camps, and the deaths of countless Danish Jews.

When The Telegraph tracked him down in 2007, he was living in a small town about 75 miles from Munich, the family's name clearly marked right on their front door. Even though the Danish courts have indicted him, courts in Munich threw out requests to have him sent back to Denmark — in spite of the fact that he was the highest-ranking and most extensively decorated Danish officer of the SS, and was active in a movement organized by the daughter of Heinrich Himmler, set up to support former SS men who have been arrested or remain fugitive.

According to The Times of Israel, Kam remained a free man for the rest of his days. He died in 2015, at 93 years old.