The Crazy Real-Life Story Of Fyodor Dostoevsky

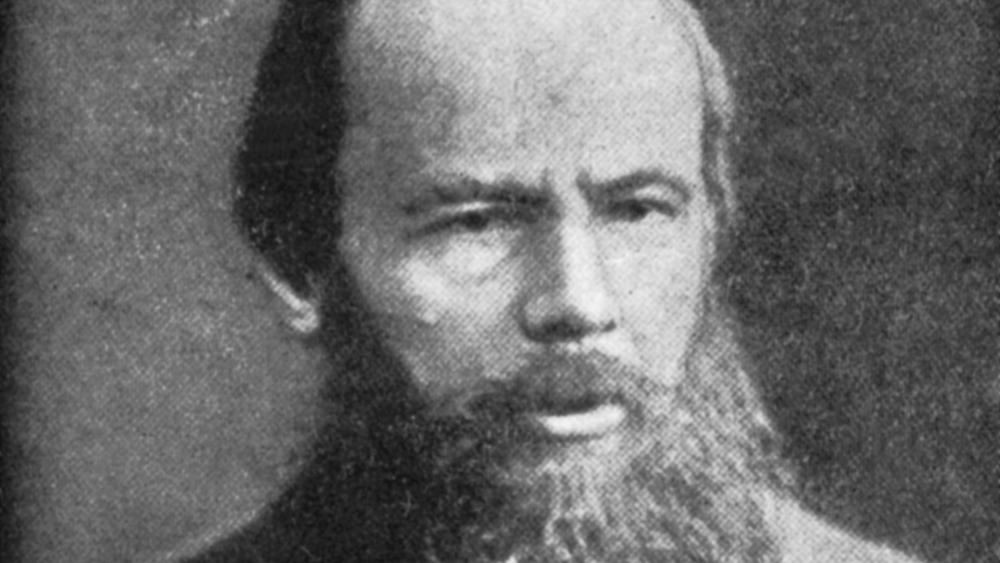

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (November 11, 1821 – February 9, 1881) is one of the most influential novelists of the last two hundred years. His works have come to be known as masterpieces of the genre, notable for their deep psychological insight and thoughtful, philosophical social critiques, while many twentieth-century commentators have named him as the father of existentialism, prefiguring the work of Jean-Paul Sartre by several decades. The Russian critic Mikhail Bakhtin even went as far as to say that Dostoevsky had made a unique contribution to the art of novel writing, arguing that the writer had created, among other innovations, the "polyphonic novel," a work in which the various world views and ideas of the characters are able to be represented as existing simultaneously, like in real life, without the didactic voice of the author suggesting what the reader should think and feel.

Virginia Woolf claimed that "Every secret of a writer's soul, every experience of his life, every quality of his mind is written large in his works." This could not be more true in the case of Dostoevsky, whose biography feeds into his fictional works significantly, and whose turbulent life impacted his world view and the nature of his writing immensely. To really get to know his life-changing works, it is worth getting an idea of the events of the life of the man himself.

Dostoevsky's tragic early life

It has been said that great writers are curious by nature, with great reserves of empathy and a need to understand the inner lives of the people around them. With Dostoevsky, this became evident at an early age. The psychologist and scholar Louis Breger notes Dostoevsky's unusual background. His strict, stern father, Mikhail, was a doctor, who lived with his wife, Maria, in a small apartment – which became extremely crowded due to the family's growing progeny – on the grounds of the Mariinsky Hospital for the Poor in a lower-class area of Moscow. Here, it is said that the young Dostoevsky, who played often in the gardens of the hospital with his older brother, also Mikhail, came into contact with a great number of the city's destitute and suffering citizens, prefiguring many of the characters who would come to populate his most famous novels. This aspect of Dostoevsky's writing differentiates him from many of the other great Russian authors of his day such as Leo Tolstoy and Ivan Turgenev, who predominantly crafted casts of characters who shared their own aristocratic backgrounds.

Dostoevsky spent some time at boarding school, where he indulged his passion for literature before his father sent him to military school in St. Petersburg at the age of 15 to study as an engineer. It was a subject the dreamy and imaginative boy hated, and his adolescence grew more intolerable when, in September 1837, his beloved mother passed away from tuberculosis.

Dostoevsky developed epilepsy after the sudden death of his father

Breger argues that Dostoevsky – whose childhood traumas are so readable throughout his work – internalized the death of his mother, whose comparative neglect of him in favor of his older brother Mikhail, who was Maria's favorite child, was already given physical expression by throat and chest ailments, illness that Breger describes as a "somatic symbol."

Whether this is true or not is open to debate, but such physical effects of stress and grief become more blatant once we consider the death of Dostoevsky's father, Mikhail Andreevich, which occurred just two years after that of his mother. Mikhail Andreevich's health deteriorated suddenly after the death of his wife, and he soon descended into alcoholism. Andrey, a younger brother of the future writer Fyodor, wrote memoirs in later life in which he claims that his father died in horrific circumstances, according to the University of British Columbia. Andrey's account states that Mikhail was brutally murdered by his own serfs after verbally abusing them while drunk. Many modern scholars strongly contest this account, but the death had a powerful effect on the young Dostoevsky, who began to have violent epileptic seizures in the aftermath of his father's passing. According to the Dostoevsky Encyclopedia, Sigmund Freud even went as far as to say that Dostoevsky's epilepsy was a direct consequence of his father's death, but whether that is the case or not, graphic descriptions of seizures and their psychological and physical effects recur throughout Dostoevsky's work.

Dostoevsky becomes famous overnight

Dostoevsky graduated from military school in 1843, and although he was given an engineering position at the rank of sublieutenant, he quickly resigned his commission to focus on mastering the art of writing, according to Britannica. Not only was literature the young Dostoevsky's passion, but the demand for novels in Russia at the time promised that, could he get published, his income would soon exceed that he could expect from a career in the Russian military.

His first published work was a translation into Russian of one of his heroes, the French writer Honoré de Balzac, but it was his own debut work – the novella, Poor Folk, first published in 1846 – that made Dostoevsky a literary star overnight when it fell into the hands of Vissarion Belinsky, a prominent Russian critic who declared that, in Dostoevsky, "A new Gogol has arrived!"

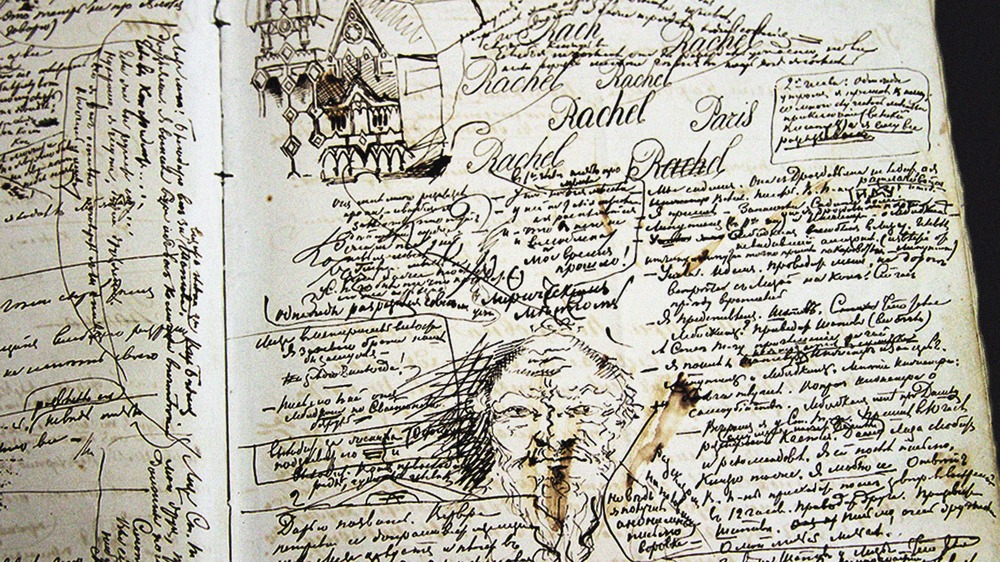

Dostoevsky soon found himself moving in Russian literary circles and celebrated as an important new voice in Russian letters. Writing about these days in his memoir, The Diary of a Writer, Dostoevsky counted them among the happiest of his life.

Political activism and arrest

Dostoevsky published a second book in 1946, according to History; The Double, which was considered a failure in its day. However, Dostoevsky continued to circulate among his literary peers, growing closer with and becoming a part of a group known as the Petrashevsky Circle. The group discussed literary matters, but also contemporary Russian politics – a dangerous activity in the nineteenth century when the country was under the thumb of Tsar Nicholas I.

Ivan Petrovich Liprandi, a secret service officer in the service of the tsar, took exception to Dostoevsky's new intellectual collective, accusing them of reading and distributing banned works of literature critical of the Russian hegemony and the country's religious practices. Though the Decembrist Revolt was almost a century gone by the time that the Petrashevsky Circle were reported for subversion, the tsar and his officials were still anxious to avoid another potential revolution. As a result, on April 23, 1849, Dostoevsky and his peers were arrested, according to the critic and biographer Konstantin Mochulsky, and taken to the high-security Peter and Paul Fortress in St. Petersburg, which housed some of Russia's most dangerous prisoners.

The Petrashevsky Circle 'execution'

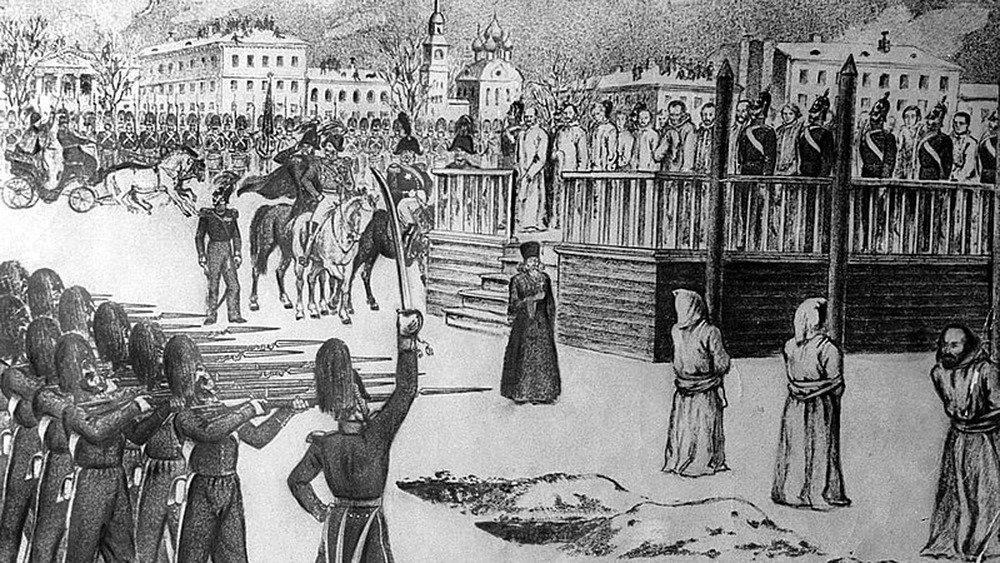

Dostoevsky and his "conspirators" were subject to eight long months behind bars, according to Britannica, until, on December 22, 1849, they were led from their cells and taken to St. Petersburg's Semyonovsky Square. There, they were told they were to be put to death: executed by firing squad. It was a bitterly cold day, the square coated in a layer of thick winter snow. According to the New York Times, Dostoevsky wrote: "[T]hey read us all our death sentence, allowed us to kiss the cross, broke a sword over each of our heads, and attired us for execution (white shirt). Then three of us were placed at the post for the execution to be carried out."

But everything was not as it seemed. Within minutes, a messenger purporting to be from the tsar appeared in the square, waving a white flag, who, according to Today I Found Out, claimed that the prisoners had been pardoned by the tsar as a "show of mercy." The whole event was staged, a mock execution in which the members of the Petrashevsky Circle believed they were about to meet their ultimate fate. Instead, the horrifying incident was just the first of a series of trials that Dostoevsky would have to endure over the course of a decade.

His mock execution would haunt Dostoevsky for the rest of his life; according to Britannica, one of the other prisoners went insane on the spot.

Dostoevsky exiled in Siberia

The mock execution was a cruel punishment, intended to shred the nerves of Dostoevsky and the rest of the Petrashevsky Circle. But the punishments that followed served a different purpose: to grind down their spirit and crush them into subservience. Following the mock execution, Dostoevsky was sent into exile in Siberia, to spend four long years in a hard labor camp in Omsk, according to Britannica.

Conditions in the camp were, frankly, horrifying. Dostoevsky, as a potential political subversive, had been labeled a "dangerous convict" by those the Russian secret service, and as a result, he was forced to share a bitterly cold, filthy barracks with hundreds of Russia's most violent and murderous prisoners, says the Dostoevsky Archive. On top of the exhausting physical labor that Dostoevsky, whose health had long been an issue, had to endure, all the prisoners in the camp were shackled. Reportedly, Dostoevsky was forced to wear heavy and burdensome chains on his legs for four long years. Somehow, Dostoevsky survived and even reportedly had the fortitude to reassure and give solace to many of his fellow prisoners.

After his four years of imprisonment, Dostoevsky was forced into the military, where he would serve for a further six years.

Dostoevsky's return to Russia and 'The House Of The Dead'

Dostoevsky's stretch in the military began after his release from Siberia on February 14, 1854, and biographers tend to agree that the writer emerged from his ordeal a changed man. In an article titled "How Siberia Concentrated His Mind," The New York Times makes the seemingly unempathetic claim that "being sent to prison was the best thing that ever happened to Fyodor Dostoevsky."

But in many ways, it is true. His harrowing experience in the Siberian labor camp was transformative. The young Dostoevsky who had written Poor Folk and The Double was, in many ways, a vain and spoiled member of the Russian literati – a "prima donna" as the New York Times put it. Though he had always had an interest in the lives of ordinary people, prison taught Dostoevsky insightful lessons in the nature of human suffering, and also human malice. It was this that he evoked in the writing of his greatest books, starting in 1860 with Notes from the House of the Dead, a brutally honest fictional account of a Siberian labor camp that charts his own spiritual reawakening. Britannica describes the change in Dostoevsky at this time as one of "regeneration."

Dostoevsky's tragic first marriage

It was while Dostoevsky was still serving in the military that he met Maria Dmitriyevna Isaeva. Isaeva was married to an alcoholic soldier, and he met the couple while tutoring the children of one the army officers, according to the Dostoevsky Archive. Dostoevsky soon fell in love with Isaeva, and the pair, who were close despite her having a husband, grew even closer when Isaeva became a widow in 1855.

Even though Isaeva was aware of Dostoevsky's dire financial circumstances, and unconvinced by his literary talent – the archive tells us that she once referred to him as " man without a future" – the two married in 1857. According to Britannia, the marriage began with Dostoevsky suffering violent epileptic seizures on his honeymoon. It was an omen of the tragedy to come: Isaeva had tuberculosis, or as it was known then "consumption," and died seven years into their marriage.

Dostoevsky later wrote: "She loved me boundlessly, I loved her too, without measure, but we did not live with her happily ever after."

Dostoevsky's devastating gambling addiction

Of the many vices that could ruin a life in nineteenth-century Russia, there was one in particular to which Dostoevsky was hopelessly addicted and which often brought him to the brink of destitution: gambling.

Dostoevsky had been introduced to gambling for money as a young man, while he was still an engineering student. Gambling was a common pastime in nineteenth-century Russia, with many gambling houses throughout the country. According to Cambridge Core, it was around the time of Dostoevsky's first marriage that gambling began to get a hold on him. The writer was having an affair with a young woman named Polina Suslova, whom he met in Paris in 1862 and who was 20 years his junior. The relationship lasted for a few years before Suslova broke off the relationship to be with another man. Shortly afterwards, Dostoevsky's wife Maria died, followed too by his older brother Mikhail, with whom he had always been especially close. These losses spurred Dostoevsky's gambling addiction, and Dostoevsky is now considered "arguably the best known compulsive gambler in history," according to the academic Richard J. Rosenthal.

Rosenthal describes how, for an eight-year period starting when Dostoevsky was 42, the writer became convinced that he had concocted a system by which to beat his favorite game, roulette. Time and again, Dostoevsky lost his and his family's money at the roulette table, and often had to leave Russia to avoid his creditors.

The tragedies of Dostoevsky's second marriage

As with his time in Siberia, Dostoevsky continued to use the trials of his own life as material for his literary work, deciding in 1863 to write a book based on his experiences of gambling addiction. According to Cambridge Core, the circumstances around the book that would turn out to be The Gambler were particularly strenuous. Dostoevsky owed a great deal of money to his publisher, Fyodor Stellovski, and to pay off his debts Dostoevsky agreed to a particularly high stakes bet: that he would write a new novel and give it to Stellovski in 30 days. Otherwise, Stellovski would own the rights to Dostoevsky's entire body of work, including any novels he would write in the future. To up his pace, Dostoevsky decided to hire a stenographer, Anna Grigorievna Snitkina, who would become Dostoevsky's second wife and remain by his side until his death. Britannica credits her with helping Dostoevsky live an ordered and stable life in which to write his great novels.

However, this marriage too was marred by tragedy, when their first child died of pneumonia at only 3-months-old. Anna gave birth again in 1869, and it was at this point – perhaps due to the loss that the family had recently suffered, though Rosenthal debates this – that Dostoevsky vowed never to gamble again. The couple had a total of four children, only two of whom survived into adulthood.

Dostoevsky wrote to clear his debts

As with The Gambler, much of Dostoevsky's prolific output is not the result of inspiration alone, but rather the prosaic necessity of earning a reasonable living. Dostoevsky's relatively humble background meant that he was always hand-to-mouth in terms of his finances, and thanks especially to his compulsive gambling habit Dostoevsky spent much of his life in considerable debt. This was especially true during his marriage to Anna, when, after their extended honeymoon traveling around Europe, the couple returned to Russia and Dostoevsky had to commit himself to a series of major literary projects to keep his family afloat, according to Britannica.

It was during this time that Dostoevsky composed some of his most famous works, beginning with Crime and Punishment, which was first published in 1866. Written around the same time as The Gambler, the novel, a compelling portrait of the mind of a murderer and the nature of morality, was hugely popular. This was followed by The Idiot, published in serial form from 1868 to 1869, Demons, published 1871-72, and, among others, his final novel, The Brothers Karamazov, published 1880.

Growing fame and failing health

By the time Dostoevsky was completing his final works, he was already considered a great master of the novel. In old age, he was reportedly inundated with admirers and well-wishers who wanted to meet him, praise him, and learn from him. However, according to the Guardian, the cocky, prodigious young man who burst into the Russian literary establishment with the publication of Poor Folk was long gone: "Dostoevsky never recovered his confidence. Even as he was writing some of the greatest books in world literature he remained consumed with anxiety that he had not yet 'established his reputation.'"

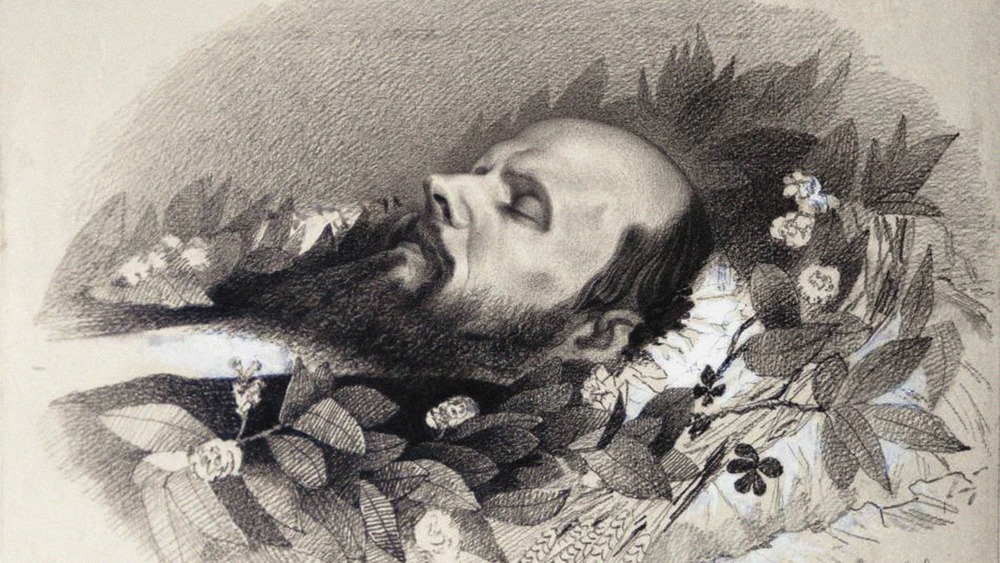

In 1880, Dostoevsky gave an important speech about the formerly-banned writer Aleksandr Pushkin. The speech was well-received, but it also attracted some negative comments from critics, who accused Dostoevsky of idolizing common people, according to The Dostoevsky Encyclopedia. Some have claimed that this criticism was enough to exacerbate the sensitive writer's already failing health, and this, along with the commotion of a raid by the tsar's secret police of the apartment of a neighbor, is blamed for Dostoevsky's death from a series of pulmonary hemorrhages in the winter of 1881. Fyodor Dostoevsky finally passed away on February 9, aged 59, surrounded by his family.