What Christmas Was Like In The Victorian Era

Most years, Christmas is pretty standard stuff. Start shopping early, forget, scramble for last-minute gifts, spend way too much money, and watch children — or pets — just play with the box anyway. There's Christmas trees, cards, cookies, and a ton of food. Santa's face is everywhere, the old favorites are on television, and every show has their annual Christmas episode. Everyone pretty much knows what the basics are and what to expect.

It wasn't always like that, though. And even just a relative stone's throw back through history, Christmas looked pretty different. While many of the traditions observed now did get their start during the Victorian era, celebrations on both sides of the pond were, well, a bit weird at first.

In all fairness, there are definitely some traditions that should make a comeback. Others should stay buried deep in the past, where people can learn about them and be grateful that no matter how bad Christmas gets, at least some of these things just aren't the norm anymore.

Christmas trees were just getting widely popular

Evergreens have been part of winter solstice celebrations for a long time. The Horticultural Society of New York says that many cultures long interpreted evergreens like trees, holly, and mistletoe as having a sacred connection nature's cycles of birth, death, and ultimately, rebirth.

The first people to bring an evergreen tree inside were the artisan guilds of Northern Germany. During the Renaissance, they started bringing a tree in and decorating it with goodies not just for children but for their guild apprentices, too.

It makes sense, then, that the tradition made its way west with Queen Victoria's consort, Prince Albert. Part of his Christmas was to send fully decorated trees to many schools and army barracks, but it wasn't until one image in particular — an image of the royal family decorating their own Christmas tree (pictured) — was printed and circulated in 1848 that the idea went viral.

It wasn't just a bit of clever marketing, either — the BBC says that Victoria and Albert did, indeed, love to decorate their own Christmas trees and then surprise their children with the final product. And that's pretty sweet — it's no wonder that the tradition took hold of the hearts of Christmas-lovers all over and eventually spread well beyond Britain's borders. For the rest of the Victorian era, more and more people were setting up and decorating trees of their own.

Everyone would have been telling Christmas ghost stories

While modern Christmastime stories include watching movies like the Ten Commandments and The Wizard of Oz, families were telling different stories during the Victorian era. According to The Guardian, Christmas Eve was the night everyone got together and told the scariest ghost stories they could.

The most famous tale is Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol — which, at a glance, is kind of weird and morbid for a 21st century Christmas story. But when it first came out in 1843, those sorts of stories were all the rage. It turns out that ghosts have been associated with Christmas — the darkest, spookiest time of the year — for centuries, but there were a few things that contributed to the popularity of the Victorians' traditional Christmas ghost stories.

For starters, the development of the middle class meant many new families were living in creepy old houses with tons of concealed doorways, secret passages, and more than a few creaks and groans. Spirituality was widely practiced, and it was believed that some knew how to break down the barriers of communication between the living and the dead. And finally, there was the fact that gas lamps used indoors could kick off some good old-fashioned hallucinations.

By the late Victorian era, the tradition was known in the United States, too. American author Henry James wrote The Turn of the Screw as a Christmas ghost story (which, as ScreenRant notes, was adapted into Netflix's The Haunting of Bly Manor).

Victorian-era Christmas cards were shockingly morbid

Christmas cards are a common obligation today, and according to the BBC, Sir Henry Cole started mass-producing Christmas cards on a commercial scale in 1843. Still, it wasn't until 1870 — and the introduction of an affordable stamp — that most people could afford to buy and send cards.

And when they did, it was super weird.

First, let's back up a bit. Pre-card, many people would exchange handwritten letters with their closest friends and family. Most of those letters continued things like good wishes for the upcoming year and might fill people in on what had happened the previous year. And once cards became more readily available, that got easier to do. They were so popular that in some cases, printers would take whatever images they had handy and slap them on a Christmas card — which led to weird ones featuring things like sad horses, kittens on dinner plates, and dogs getting their portraits painted by monkeys. By 1880, people were sending 11.5 million Christmas cards a year.

There were also a lot of people sending cards with dead birds on them — and buckle up, it's going to get weird. Part of the reason for this trend, says Hyperallergic, is because killing a robin or wren on December 26 — Wren Day — was thought to be good luck. So getting a card with a dead bird was essentially getting a cheery card wishing the recipient all the best. Creepy.

Christmastime parlor games were hilarious and sometimes incredibly dangerous

There were no Netflix or football games for Victorian-era revelers to enjoy, so what did they do when dinner was finished and the fire was burning down? Play parlor games, of course!

Let's start with an odd game called Prussian exercises. According to the Independent, players would stand in a line, and the "captain" would give them orders — like telling them to fold their arms, jump up and down, whatever-you-please. At the end, they'd be ordered to kneel and hold their arms out in front of them... at which point the "soldier" on one end would shove everyone over. Fun!

At the other end of the scale are hilariously dangerous games, like one called Snapdragon. In this one, raisins and brandy would be put into a bowl, the lights would go off, and the contents of said bowl would be set on fire. Whoever had the most success eating the raisins — with the bowl still on fire — without burning themselves or setting anything else on fire was the winner... if you could call anyone here a winner.

Those are just a couple. There was also Are You There, Moriarty?, which involved blindfolds and hitting people with rolled-up newspapers, and Squeak, Piggy, Squeak, which Cape May says was a game where a blindfolded person had to guess the identity of the person who's squealing like a pig.

Gift giving got more complicated

Gifts are one of the biggest parts of Christmas today, and finding the right one can definitely be a challenge. In the early years of the Victorian era, people were already giving each other gifts, but it wasn't nearly as complicated — or as expensive — as it is today. According to the BBC, most gifts had originally been given at New Year's, but as Christmas became more important, the gift giving shifted. At first, a typical Victorian-era family might hang small presents from their tree, typically things like handmade decorations and crafts, fruits and nuts, or sweets.

As the years went by, gifts got bigger, more expensive, and more people started buying presents. They were moved to under the tree instead of on it, and according to writer and historian Mimi Matthews, then it got really complicated.

Ladies, for example, were typically expected to only give gifts to the men they were related to or married to. Then, they needed to make sure it wasn't too expensive or too intimate, and among the gifts advised by Victorian-era publications were practical things like shaving kits, soaps, gold pens, tobacco boxes, or desk sets. Better yet, she could make something.

When it came time for the ladies to receive gifts, they might expect something like soaps and perfumes, jewelry, a handkerchief or shawl, knitting needles, or fruit, candy, and flowers, depending on social status, whether or not the lady was married, and how she was related to the giver.

Goose clubs helped people put Christmas dinner on the table

When it comes to traditional Christmas dinner, the British Poultry Council says that a goose has been the cream of the crop for centuries. Geese are typically in season twice a year, and one of those times is — conveniently — Christmas.

Not everyone could afford a Christmas goose, though, so according to the British Library, there were a few things people could do. Some might opt for a Christmas turkey instead, while others might take part in a Goose Club. Basically, a family might pay into the club a little bit each week for several months, and by the time Christmas rolled around, they'd contributed enough to buy their holiday goose. Sometimes, they'd also get a bottle of gin with their bird, and other times, they'd get someone to cook it for them. Most houses didn't have the ovens needed to cook a whole goose, so many bakers would keep their ovens going and do the cooking for those who needed some help.

By the 1840s, imported poultry meant geese were pretty readily available, and many would serve them up alongside other traditional Christmas foods, like Christmas puddings, mince pies, and mulled wine.

Santa started to become a thing again

Santa might be synonymous with Christmas today, but that wasn't always the case. According to National Geographic, St. Nicholas Day was originally Dec. 6. He had a centuries-long history of being a gift-giver, but fast forward to the 1500s and the Protestant Reformation. Then, St. Nicholas kind of fell out of favor, the special day was moved to Christmas, and the special guy became Jesus. He needed an alter-ego to deal with the bad kids, though, and that's where figures like Krampus and Pelznickel came in.

And that's where we come into the Victorian era, with no widespread belief in a magical, mystical, gift-delivering man from the North Pole. That's also when things started to change, in large part thanks to Victorian-era writers, poets, and cartoonists who wanted to make Christmas a more family-friendly affair.

Victorian-parents would have had new literature to read their little ones around Christmas, like the 1821 poem, The Children's Friend. That's one of the first instances where St. Nicholas keeps his gift-giving abilities but is stripped of his religious connotations. That was quickly followed by A Visit From St. Nicholas — also known as The Night Before Christmas — the very next year. And as the 19th century continued, the idea of a chubby, jolly, bearded Santa became more and more popular. Santa as we know him was created by an American political cartoonist named Thomas Nast, and Christmas has never been the same.

Christmas crackers were a huge deal

According to Victoriana Magazine, one of the things that was often given as a gift was a little love token called a kiss. It wasn't an actual kiss in the traditional sense of the gesture, but it was instead a little bit of twisted tissue paper that had a piece of candy inside, along with a little poem or verse. It was a French tradition that had spread to England, and it was also in the Victorian era that England improved on it immensely.

In the 1850s, Historic UK says that a London confectioner named Tom Smith made something more like the Christmas crackers of today. In addition to the little piece of candy and the love note, he was inspired to make a bigger package that popped when someone pulled the halves apart. The idea supposedly came from a log that crackled away on the fire, and it wasn't long after that some of the candy prizes were replaced by little gifts. By 1900, they also contained a little paper hat, which means Victorians could look just as goofy as people can today.

Early Victorian-era Americans didn't have a cohesive idea of Christmas

The Victorian era isn't all about England, and at the same time the British were developing Christmas traditions that are still familiar today, America was having a little more trouble with the holiday.

According to History Today, America before about 1850 didn't really have much in the way of a cohesive idea of what Christmas was and how it should be celebrated. (History says it wasn't even declared a federal holiday until 1870!)

What you did depended greatly on where you were. Puritan communities, for example, didn't celebrate at all, for the simple reason that the Bible didn't tell them to. For others, it just wasn't a big deal. And for some who had held onto close ties with Britain — like Virginia planters — they took the opportunity to celebrate by hunting, feasting, dancing, and visiting friends and family. That was what they envisioned Christmas to be like back in England.

Things changed as the century went on, and a growing population started making life move faster and faster. With that came a growing desire for a holiday centered around kindness, community, and a peaceful time where people could gather and simply slow down to enjoy each others' company.

Christmas traditions became much more national around the Civil War

By 1900, History Today says about one in five American homes had picked up on the tradition of the Christmas tree and were doing it themselves. Why such a switch? Because of the Civil War.

According to David Anderson, an American history professor at Swansea University (via The Conversation), the Civil War made everyone — north and south — stop to take stock of what really mattered — family.

At home, Christmas became a time when women would volunteer at hospitals or make things to send to the soldiers — whether it was a new piece of clothing or a gift box of food, it was immensely appreciated. And as for those soldiers, so far from home, they made a serious effort to get a little Christmas cheer wherever they were. Small trees were set up in tents and decorated, games were played, songs were sung, and soldiers told stories about the families they'd left behind. They wrote home and dreamed of a Christmas where they could spend the day with their families instead of at war, and History says it was that collective longing that meant when the war was over and the survivors returned, Christmas was suddenly much, much more important.

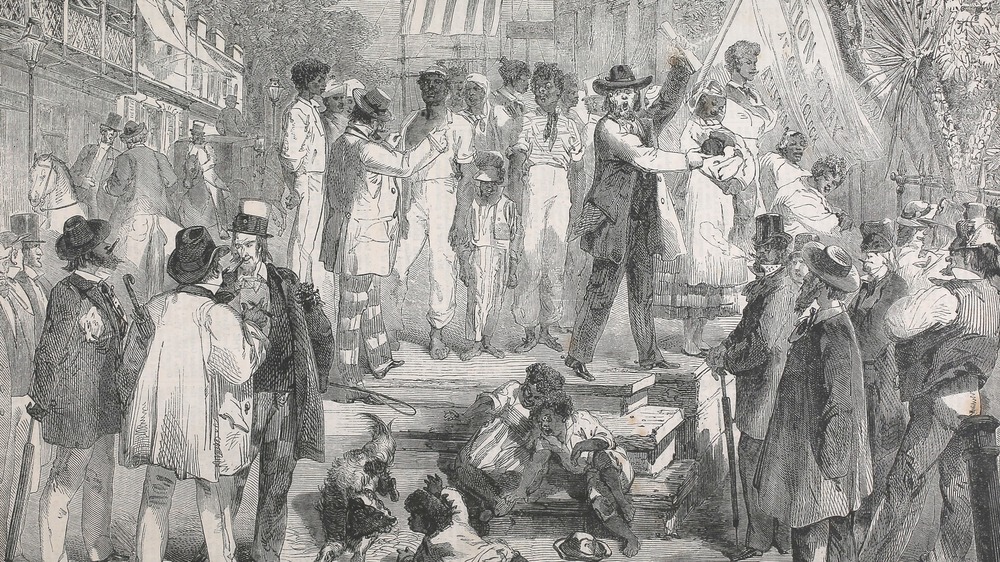

Christmas on a slave plantation

According to historians Shauna Bigham and Robert E. May (via History), many slave owners took Christmas as an opportunity to demonstrate what good, kind people they were. Some gave their slaves extra food, alcohol, and sometimes even gifts, but it wasn't just charity — in return, slaves were expected to demonstrate just how grateful they were.

The Guardian says that Christmas day was often filled with dancing, singing, and in some places, feasting and gift giving. Children might have been given treats like oranges and chocolate, while adults may have received tobacco or a piece of new clothing. Large plantations might have laid out a feast of turkey and alcohol. Don't worry, there's a terrible footnote to this.

Christmastime was generally a period between crops and between work. And Christmas was followed almost immediately by Hiring Day.

Time says that when it came to the day of the year a slave dreaded the most, it was Hiring Day — also known as Heartbreak Day. Typically, plantation owners would rent out slaves under contracts that would start on January 1 and run for a year. January 1 was also a common day for massive auctions and sales. Even though the slave trade was ongoing all year around, the frequency — and near guarantee — that came with Heartbreak Day meant that many families spent Christmas wondering if they only had a few more days left with their loved ones before they were separated.

The Salvation Army's red kettles

There are a few signs that the Christmas season is in full swing, and one of those signs are the Salvation Army's red kettles. Chances are pretty good you'll hear their bell ringers before you'll see the kettles, and there's no denying it — they're everywhere during the Christmas season. And strangely, Victorian-era shoppers saw them out in full force, too.

Diane Winston, professor of Media & Religion at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism says (via The Conversation) that the Salvation Army was founded back in 1878 by an English evangelical preacher named William Booth. Booth — who referred to himself as The General and dressed the members of his army in uniforms — sent a first detachment of "troops" to New York in 1880. On both sides of the pond, they had similar goals — to convert sinners and help those in need.

Fast forward to 1891. That's when Salvation Army Capt. Joseph McFee decided he wanted to raise enough money so that he could organize a Christmas feast for San Francisco's less fortunate. He grabbed a crab pot, hung it from a tripod, and the rest is history. It wasn't long before the kettles were popping up across the United States, and the money raised originally went to providing Christmas dinner for thousands of people every year.

Today, they're still one of the country's top-grossing charities. In 2018 alone, their bell-ringers raised $142.7 million.