The Tragic True Story Of How Philadelphia Bombed Its Residents In 1985

On the afternoon of May 13, 1985, the city of Philadelphia did the unthinkable and dropped a bomb on one of its own residential neighborhoods. City officials claimed that the bomb was dropped as a result of a civil eviction, but the incident was part of a planned effort to "liquidate the MOVE organization" after years of assault. The bomb ended up causing a fire that destroyed and damaged over 100 houses and left over 200 Philadelphia residents homeless.

Before the bombing, the city of Philadelphia regularly antagonized MOVE members by shutting off the water and power to their homes and refusing to pick up the trash. Meanwhile, MOVE loudly demonstrated for animal rights, racial justice, and environmental protections.

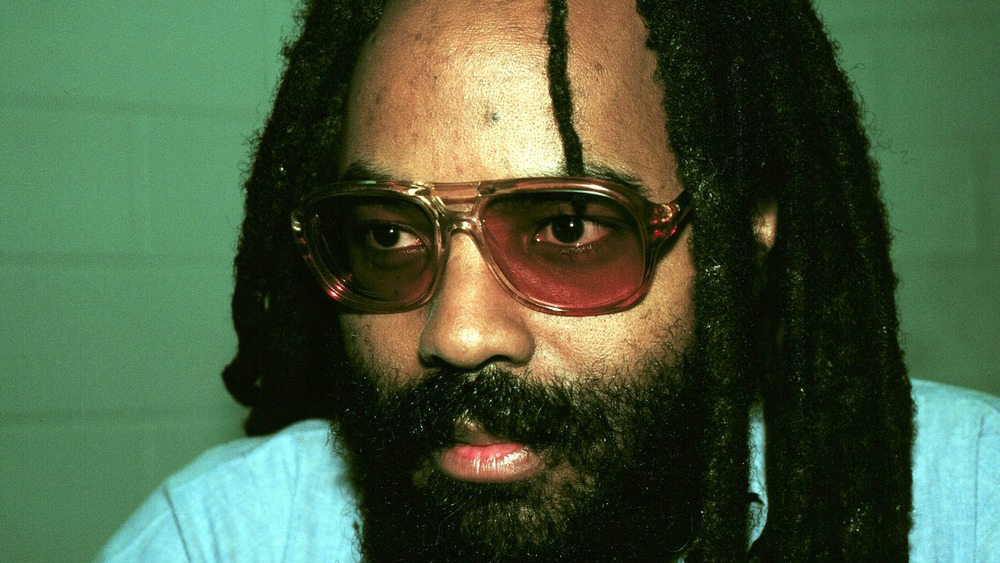

Despite the best efforts of government officials and police officers, MOVE wasn't completely exterminated and they have continued their campaign to free political prisoners in the United States, many of whom are MOVE members like Mumia Abu-Jamal. In 2020, the city of Philadelphia issued a "formal apology" for the bombing. This is the tragic true story of how Philadelphia bombed its residents in 1985.

What is MOVE?

Founded in 1972 by John Africa, MOVE is "an organization, or a family" of Black activists in Philadelphia. Their work was founded as a revolution trying to put an end to industrial pollution and the "enslavement of all life." The name MOVE isn't an acronym and is instead meant to exemplify the motion and activity inherent in life itself. With beliefs rooted in anti-capitalism, anarcho-primitivism, and black liberation, MOVE works toward exposing the crimes of government officials at every level. According to The Guardian, the causes they have demonstrated against include animal enslavement, industrial pollution, and police brutality. Members weren't "one particular age or race," and were united by a shared "history of hardship."

According to Black Past, MOVE was initially called The Christian Movement for Life, and with the help of Donald Glassey, who later turned into a police informant, John Africa compiled a text called "The Guidelines," which became the primary source of the principles for the organization.

In 1974, Glassey purchased a house on 33rd and Pearl Street in Powelton Village, which MOVE used as a home and headquarters. Some MOVE members would stage disruptive but non-violent protests across the city of Philadelphia, while those who remained in the neighborhood used a bullhorn to amplify their messages, sometimes at all hours of the day and night.

MOVE's relationship with their Philadelphia neighbors

Even though the government later used neighbor complaints to justify the 1985 bombing, MOVE's relationship with their neighbors was a complicated one. Residents of Powelton Village shared many of MOVE's countercultural values and many were activists and protestors. But according to West Philadelphia Collective History, sometimes the residents of Powelton Village thought that MOVE was going too far. As a form of composting, MOVE disposed of all their trash in the backyard. And when the refuse attracted rats and cockroaches, MOVE refused to remove them since they considered there to be no distinction between human rights and animal rights.

But while they weren't necessarily "ideal neighbors," the community upheld one another. According to Mumia Abu-Jamal, when the Philadelphia police cut off the MOVE house's electricity and water during their siege, "people from the neighborhood and supporters from the city supplied MOVE with the basic necessities."

According to "The MOVE Crisis in Philadelphia" by Hizkias Assefa and Paul Wahrhaftig, tensions mounted when some of MOVE's neighbors went to a zoning board hearing to oppose MOVE's application for a dog kennel permit. The neighbors later complained that some MOVE members had "verbally harassed them."

Life Africa

One of the turning points for the MOVE organization was when Life Africa was murdered by the Philadelphia police at the age of three weeks in 1976. According to "The MOVE Crisis in Philadelphia," at the end of March, MOVE members decided to throw a party for some of their associates who'd been released from jail. But before long, a fight broke out between the police and the MOVE members. While police claimed that they came in response to neighbor complaints, Phil Africa claimed that police had been following them since they'd been released.

At least 10 cars of police officers arrived and proceeded to beat the MOVE members. Trying to protect her husband, Janine Africa was holding Life when she was thrown to the ground and repeatedly stomped on. Her baby's skull was crushed.

When MOVE demanded justice for the murder of Life, "police denied the charge, saying that no baby was involved in the conflict." They also demanded that MOVE show a birth certificate to prove that a baby even existed, knowing that since MOVE members believed in natural home births and didn't register their children, they would be unable to produce a birth certificate. Interviews with the neighbors made it clear that Life existed, but it took the visit of two city councilmen and the disruption of Life's burial site to prove it. Meanwhile, no officer was ever charged with infanticide. Instead, the men who were beaten that night were charged with "aggravated assault on police officers."

Harassment of MOVE

After this incident, MOVE members started taking the position that although MOVE was non-violent, they would "counter with violence if attacked." However, Mayor Frank Rizzo considered MOVE to be a terrorist organization almost from its inception. And when MOVE started focusing on police brutality in 1974, this led to increased confrontations with police. According to "The MOVE Crisis in Philadelphia," it's believed that in 1975, over a 7-month period, "MOVE members had been arrested on misdemeanor charges more than 150 times, fined $15,000, and sentenced to several years in jail."

City officials repeatedly tried to enter the house in 1977 to inspect the living conditions, but MOVE refused to allow them to enter, stating that "any inspection violates the sanctity of our home, and we will consider any incursion as a declaration of war."

MOVE members barricaded themselves inside the house while police surveilled them around the clock with at least 100 plainclothes officers. Several MOVE members who were captured were charged and convicted of conspiracy charges over the next year. In March 1978, Mayor Rizzo decided to blockade the house and "deny MOVE access to city water" in an attempt to drive the people out of the house.

The 1978 shoot-out

On May 3, 1978, the court ordered a compromise. MOVE would allow an inspection of the house, leave the house by August 1st, and surrender their weapons. In return, the city "agreed not to arrest members who had no outstanding warrants and to expedite the trials of jailed members." While the weapons were handed over, MOVE members remained in the house.

According to NPR, MOVE members didn't leave the house by the August 1 deadline. In response, the Court of Common Pleas issued arrest warrants for the MOVE members still in residence. Police arrived in SWAT teams, armed with teargas, water cannons, machine guns, and bulldozers, at dawn on August 8. As MOVE residents fled to the basement, smoke bombs and two water cannons were unleashed as bulldozers clawed at the house. At 8:15 AM, during this eviction, officer James Ramp was shot and killed.

Nine MOVE members were charged for the officer's death, although many MOVE members claim that at the time of the eviction, "the arms that MOVE had were inoperable." According to Delbert Africa, "No one in the house had any gunshot residue, none of us had fingerprints on any of the weapons they claim came out of the house." And even once the MOVE members had surrendered, police officers attacked once more, grabbing Delbert Africa, throwing him to the ground, and stomping on him repeatedly while he was unarmed and half-naked.

MOVE in Cobbs Creek

In 1980, the nine MOVE members who were convicted of Ramp's death received 30 to 100 years in prison. The last incarcerated member was released on parole on February 7, 2020.

By 1982, MOVE had created a new headquarters at 6221 Osage Avenue in West Philadelphia. But their repeated demands for the release of their imprisoned members over a loudspeaker once more led to frustrations with their neighbors. And according to "The MOVE Crisis in Philadelphia," MOVE wasn't trying to refrain from antagonizing their neighbors. They believed that by alienating the neighbors, they could "bring the city to the point of confrontation or compromise" in order to negotiate the release of the MOVE 9 arrested as a result of the 1978 eviction.

However, the city repeatedly ignored the complaints of the neighbors, and although the city later claimed that the 1985 bombing was simply the result of a civil eviction, as Mumia Abu-Jamal has stated, "You don't attempt to evict people from their homes with dynamite. You don't evacuate the whole neighborhood at 7 o'clock in the morning if all you want is an eviction ... This was a premeditated attempt to liquidate the MOVE organization."

The arrest warrants

On May 12, 1985, Mayor W. Wilson Goode approved a plan to execute arrest warrants for the adults inside the MOVE house on Osage Avenue on May 13, 1985. According to "The MOVE Crisis in Philadelphia," the Philadelphia police developed the plan with little-to-no supervision from the police commissioner, and on May 11, arrest and search warrants were activated by District Attorney Ed Rendell.

Mayor Goode claimed that he'd ordered all the children in the MOVE house to be removed before any action took place, but the police made absolutely no attempt to actually do so. However, police did evacuate the neighbors of 6221 Osage Avenue late in the night on May 12 and over 500 police officers took their positions amongst and within the empty houses. And although Mayor Goode also claimed that he'd ordered that "none of the police officers involved in the 1978 Powelton shoot-out should participate in this eviction plan," several officers who were involved in the shoot-out were also part of the assault force on Osage.

According to NPR, at around 5:30 in the morning on May 13, the police started yelling for people to come out of the MOVE compound. Around 6 AM, police repeated their final warning, and someone from inside the MOVE house allegedly fired at the police. Police shot back, firing "10,000 rounds of ammunition at the MOVE compound over the next 90 minutes."

Dropping a bomb and missing

SWAT teams tried and failed to blast holes into the MOVE house and the police repeatedly set off explosions trying to enter the building. But no one was getting in and no one was coming out. Police yelled repeatedly through the loudspeakers "Attention MOVE: This is America!" This lasted throughout the day until Goode gave the "go-ahead to drop a makeshift bomb on the MOVE compound in an attempt to destroy the bunker on its roof" at 5:27 PM, 12 hours after the siege started.

According to "The MOVE Crisis in Philadelphia," the bomb was dropped atop the bunker on the top of the MOVE house in an attempt to dislodge it. "It failed to dislodge the bunker immediately, but it ignited the gasoline tank and started a fire."

While former police officers claim that "the bomb missed its intended target," Mumia Abu-Jamal claims that "that's the impression that they would like you to have. In fact, it was deeply planned at least a year in advance, and they achieved a lot of their objectives." Six MOVE adult members, including founder John Africa, and five MOVE children died as a result of the fire.

A Philadelphia neighborhood burns

Although the fire started after the bomb was dropped at 5:27 PM, and quickly engulfed the MOVE house along with the neighboring homes, the fire department didn't turn their hoses onto the fire until 6:32 PM, more than an entire hour later.

According to NPR, "the firefighters were ordered by [Gregore] Sambor, the police commissioner, to stand down" and to let the fire burn. Active steps weren't taken to fight the fire until 9:30 PM, four hours after the fire started burning. But by that point, the fire was out of control and it took until 11:41 PM to contain the flames.

Since the streets of Philadelphia are narrow, it was easy for the fire to jump from burning trees on the north side to homes on the south side. Almost two square blocks of residential homes ended up burning. At least 61 homes were destroyed and 110 homes were damaged, resulting in over 250 homeless men, women, and children. Ramona Africa and 13-year-old Birdie Africa were the only MOVE survivors of the bombing.

The mayor of Philadelphia establishes a commission to investigate

With the attack broadcast live throughout the day, countless people questioned the decisions made by police and Mayor Goode. In response, Mayor Goode established an 11-person commission to independently investigate what had happened with the MOVE bombing.

On March 6, 1986, the Philadelphia Special Investigation Commission issued its findings. According to "The MOVE Crisis in Philadelphia," the commission discovered that only four MOVE members in the house had warrants out for their arrest out of the 13 MOVE members in the house. The commission also reported that there had been practically no attempt at negotiations. In addition, the commission discovered that "once the house was on fire some members and children tried to escape from the building, but were prevented by police gunfire."

The commission describes the actions of the police and the mayor as "grossly negligent" and "unconscionable" and went on to recommend that the entire incident be fully investigated by the United States Department of Justice and the District Attorney. Meanwhile, Goode was re-elected as mayor in 1986.

The only criminal charge from the bombing

In 1988, a Philadelphia grand jury issued a 279-page report, after spending two years investigating, stating that Mayor Goode and his aides were absolved of criminal intent. No criminal charges were brought against city officials. Despite this report and the recommendation of the commission, not a single city official was convicted for the bombing and the resulting loss of life and destruction of property.

The only person criminally charged and convicted was Ramona Africa, the only surviving adult MOVE member of the bombing. In January 1986, Ramona Africa stood trial for "aggravated assault, riot, and conspiracy; her bail was set at $2.5 million." According to "All Things Censored" by Mumia Abu-Jamal, Ramona Africa was sentenced on April 14th, 1986 to 16 months to seven years. According to The Guardian, Ramona Africa served the full seven years. She could have gotten out on parole earlier, but she refused to acquiesce to the parole board's demand that "she dissociate herself from MOVE."

During the conclusion of Ramona Africa's trial, Philadelphia Common Pleas Court Judge Michael Stiles told the jurors "not to consider any wrongdoing done by officials because officials would be dealt with and held accountable in 'other' proceedings." As of 2020, no officials have been held accountable in any of the "other" proceedings.

What happened to Philadelphia's displaced residents?

After the fire, the remaining members of MOVE lived in various houses around Philadelphia, keeping a low profile and focusing on the release of the MOVE 9 and Mumia Abu-Jamal. The remaining residents of the neighborhood who'd lost their homes were then subjected to a "scandalously long delay and ineptitude" when it came to replacing the destroyed houses.

Initially, the city had planned to resettle the 253 homeless residents by Christmas, 1985. But by Christmas, only five new homes had been built. The homes were finally built and ready for occupancy by the summer of 1986, but they were so poorly constructed that within the first year roofs were leaking, beams were sagging, and walls were cracking. According to The New York Times, the two building contractors hired by the Goode administration were charged with stealing over $200,000 in city funds during the rebuilding.

By 2000, the city realized that it would cost $10 million to renovate the houses in order to meet building-code standards, which would also raise the average cost of each house to over $400,000. Deciding that it was cheaper for the city "to purchase and board up the houses until someone could figure out what to do with them," the city bought 36 of the houses at $150,000 each. Many remained boarded up for years until 2020 when all 36 houses were finally rebuilt.

Suing the city of Philadelphia

Ramona Africa filed a civil suit in 1987, soon after her conviction, but it didn't come to trial until 1996 in federal court. Several people in the city government even had to be subpoenaed.

The trial lasted from April to June and according to Black Past, Ramona Africa and the relatives of John and Frank Africa were awarded a settlement of $1.5 million. Although almost all of the settlement was to be paid by the city, a symbolic amount was charged to Fire Commissioner William Richmond and Police Commissioner Gregore Sambor. But before the end of the summer, a federal judge ruled that "as city employees enacting their public responsibilities on May 13, 1985, they were entitled to immunity."

According to West Philadelphia Collaborative History, although Ramona Africa and the city both attempted to have the judgments against Richmond and Sambor reinstated, both of their appeals were rejected in September 1998. By 1992, the city of Philadelphia also paid out $2.5 million for the "wrongful death suits brought on behalf of the five children who died."

The bones of children

In April 2021, it was revealed that some of the remains of two girls who died in the bombing, Katricia Dotson (Tree Africa) and Delisha Africa, were never reunited with their families. Instead, The Philadelphia Inquirer reports that the bones of the two children were given to anthropologists Alan Mann and Janet Monge for analysis and to reportedly confirm the children's identity at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. But even after the identities were confirmed, the bones were kept instead of being reunited with their families. Carolyn Rouse, the chair of Princeton's anthropology department, claimed that "nobody came to claim the remains," conveniently ignoring the fact that Delisha's parents were imprisoned at the time.

According to Billy Penn, Mann and Monge reportedly maintained possession of the bones for decades, with Monge even going as far as to use the bones "as teaching materials in a public online forensics course."

After the story broke about the Penn Museum keeping the bones, a spokesperson for Penn Museum released a statement claiming that the remains in the museum's possession were given back to the Africa Family on July 2, 2021. They also claimed that the Tucker Law Group's independent investigation determined that they only had a single set of remains as opposed to two. However, due to the "bungled chain of custody," according to Hyperallergic, it's argued that the City of Philadelphia should do its own investigation.