The History Of The National Christmas Tree Explained

For almost 100 years, the National Christmas Tree has been an institution in the United States' celebration of Christmas. Every year, a large, decorated evergreen tree placed or planted somewhere within spitting distance of the White House and lit by the president himself becomes the centerpiece of weeks of festivities meant to unite the country in a spirit of festive good cheer.

But the execution of this tradition has had its ups and downs. From its kind of shady institution for secretly capitalist reasons, to technical problems, to protests and legal battles over the fact that not everyone feels represented by an 80-foot symbol of someone else's religion, the life of a tree meant to represent peace and happiness for all Americans hasn't been an easy one. Here is the story of how Christmas trees went from being banned in the White House to being as plentiful as the stars on the flag themselves.

Forerunners to the National Christmas Tree

While Christmas trees seem as American as apple pie these days, that wasn't always the case. As History explains, the American colonies' Puritan past meant they didn't even like Christmas as a concept, let alone the festive accoutrement that came with it. It was largely German immigrants bringing their love of Christmas along with them to America in the 19th century that helped start the spread of Christmas trees through the U.S., before the tradition was finally clinched in a reproduction of a famous British illustration of Queen Victoria celebrating Christmas with a tree brought in by her German husband Prince Albert. After this, Christmas trees became fashionable among East Coast socialites and then spread from there.

The earliest Christmas tree in the White House came in 1853, when the 14th president Franklin Pierce had a tree on the White House lawn decorated for public view. Benjamin Harrison was the first to have a tree inside the White House, which was lit with candles. Theodore Roosevelt, known for his strong conservationist ideals, didn't want to have a tree cut down just for decoration, but his young son managed to set one up inside a large closet in the executive mansion anyway. The clearest forerunner to the current National Christmas Tree, however, was the U.S. Capitol Tree, first displayed in 1912 during Woodrow Wilson's first term of office.

The National Christmas Tree was a scheme to sell light bulbs

It is generally agreed that the key figure in the development of the idea of a National Community Christmas Tree meant to be the tree of the entire United States was a man named Frederick Feiker. According to the Barre Montpelier Times Argus, Feiker was an adviser to Herbert Hoover, who at the time was the U.S. Secretary of Commerce. Using his connections and the influence of some Senators, Feiker was able to get a meeting with President Calvin Coolidge in order to present his idea of a National Tree. He told Coolidge that he wanted to institute a tradition that would serve as a symbol of community for all Americans and also emphasize the importance of Christmas as a religious holiday (it would seem those two goals might be at odds, but okay).

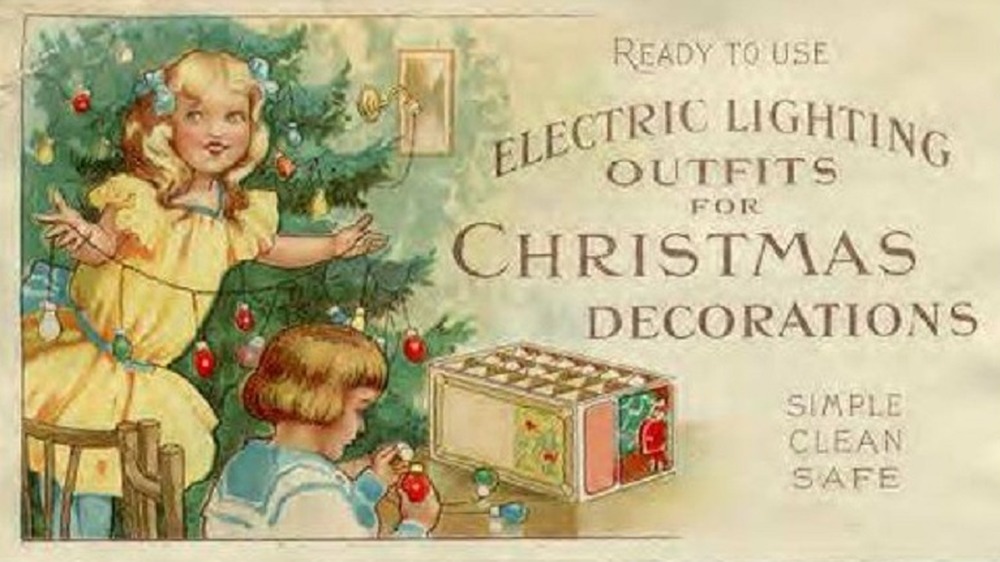

What went unspoken was Feiker's ulterior motive. Besides being an adviser to the Commerce Secretary, Feiker was also the vice president of the Society for Electrical Development, an industry trade group for electrical devices. For this reason, the tree was ultimately meaningless. What was important was the lights. In 1923, most Americans were still decorating their Christmas trees with candles, as electric lights for decoration were seen as an unnecessary luxury. But if Feiker could set it up so that the president could be seen lighting up a tree every year? That could move some units. And, yeah. It worked.

Calvin Coolidge lit the first National Tree

After the successful lobbying of Frederick Feiker and the Society for Electrical Development, the first National Christmas Tree was lit by President Calvin Coolidge in 1923. According to the National Parks Service, the first tree was erected in the park south of the White House known as the Ellipse, as the President's wife, Grace Coolidge, had already scheduled a caroling event on the White House North Lawn. The tree was a 48-foot balsam fir donated from Vermont, Coolidge's home state. It held 25,000 electric lights colored red, green, and white, all donated by the Electric League of Washington.

The events were kicked off at 5pm on Christmas Eve when President Coolidge turned on the lights, surely much to Frederick Feiker's pleasure. A choir from Epiphany Church led attendants in carols, with accompaniment from a U.S. Marine Band quartet, followed by an hour-long performance by the full Marine Band. Mrs. Coolidge's caroling event took place as well, at 9pm that night, when hundreds of singers led by the First Congregational Church sang carols from lyrics that had been printed in the evening newspaper. After that, a marginally more modest 72-voice choir continued the singing. It is also notable but perhaps not surprising that this event was segregated. Black groups were not allowed onto the grounds until after midnight when all of the white spectators had dispersed.

The National Christmas Tree goes live

Although the original National Christmas Tree in 1923 had been cut down in Vermont and transported to the White House, the following year Coolidge was feeling pressure from the American Forestry Association to discourage Americans from using cut trees to decorate for Christmas. As the National Parks Service explains, this led to the Forestry Association donating a live Norway spruce for use as the National Tree that year. This resulted in the location of the tree being moved in 1924. The Ellipse, which was the location of the tree the previous year, was the site of many events throughout the year, and having an enormous, permanently installed tree in the middle of it would take up too much space. So in 1924, the Forestry Association tree was planted in Sherman Plaza, an area to the east of the White House near the Treasury Building.

This first living tree was not to be the last. In fact, live trees were used as the National Tree from 1924 to 1953 in various locations near the White House. However, in 1954 the ceremony was moved back to the Ellipse in order to accommodate the expansion of the event, and a cut tree was deemed necessary again. Letter writing campaigns from concerned citizens brought about the return of the use of live trees, which have now been the norm since 1973.

Relocation during the Great Depression

From 1924 to 1933, the National Christmas Tree made its home in Sherman Plaza, where the first live tree had been planted by the American Forestry Association. However, according to the National Parks Service, by the end of 1933, it had been decided that the landscaping of Sherman Plaza should only contain willow oaks, and so a towering Norway spruce didn't really fit that aesthetic. As a result, the tree would have to be moved again. Two Koster blue spruce had already been purchased to replace the previous tree that was looking pretty scraggly by that time. The idea behind purchasing two trees was that with two trees they could alternate between them every year and reduce the amount of wear and tear done to the trees by decorations and lights, allowing them to last longer.

After some quibbling about placement, two different new trees, firs from North Carolina, were planted in Lafayette Park, on either side of a statue of Andrew Jackson. President Franklin Roosevelt, making his address at the tree, used the statue of Jackson as a talking point, saying that the American people–at the time hip-deep in the Great Depression–should remain, like Jackson, "unstained and unafraid." (No word on whether he suggested they do a genocide like Jackson, too.) The National Tree remained at Lafayette Park until 1939, when it was moved back to the Ellipse.

The life of a Christmas tree during wartime

The National Christmas Tree remained in the Ellipse for the 1939 and 1940 season, but in 1941 was moved to the White House grounds for the first time. According to the National Parks Service, President Roosevelt believed that the "proper place for the tree is right next to the fence at the south end of the White House grounds." He hadn't cared for the Ellipse location in the previous years and wanted to invite people to "come into [his] yard." The tradition of two live trees was continued despite this move, and 1941 saw two 25-foot Oriental spruces planted on the White House South Lawn. The National Tree ceremony remained on the South Lawn until it moved back to the Ellipse in 1954, though one of the two South Lawn trees was still standing as recently as 1998.

You may have heard that in addition to Christmas, another significant event happened in December of 1941 which had an effect on the National Tree ceremony. Because of the attack on Pearl Harbor just weeks before, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was in town to discuss strategy with FDR. As a result, attendees of the tree ceremony got remarks from two historic world leaders in one go. During the rest of the war, however, the National Tree was not lit, both because the lights were seen as a security risk and in an effort to ration electricity.

The birth of the Pageant of Peace

The reason that the National Christmas Tree was moved away from the White House lawn and back to the Ellipse, which also meant the return to cut trees, was that by 1954 the annual ceremony was exploding in popularity, thanks in part to the fact that the tree-lighting had been televised since 1946. According to the National Parks Service, 1954 saw the expansion of the tree-lighting from a single-night event in which the President lit the tree and said remarks after a choir and a military band did some carols, into a three-week event known as the Pageant of Peace. Pressure from the popularity of the event on television and from local religious groups requesting the inclusion of a Nativity scene led to much more ado being made about the National Tree.

In 1954, the first Pageant of Peace included nightly performances at the Ellipse (a space which allowed for much more public attendance than the White House lawn) of concerts and religious services, as well as a life-sized Nativity and rows of exhibition booths. On the night before the lighting, Santa Claus arrived in a sleigh pulled by live reindeer. The Pageant of Peace was an enormous success, with tens of thousands of attendees a day, and the weeks-long series of events continues to this day. Well, not in 2020. But all the years before that.

Why have one tree when you can have 60?

The Pageant of Peace was not the only new Christmas tradition added to the National Christmas Tree ceremony in 1954. The official page for the National Christmas Tree Lighting says that in that year, the Pathway of Peace was also introduced (however, the Parks Service says 1955, so you come to your own conclusions). The Pathway of Peace meant that the Community Tree was no longer the only tree featured in the ceremony. Now there were dozens of trees lined up in a double row leading toward the Community Tree in the Ellipse. These trees represented the various states and territories of the United States, and the total number has varied over the years, but the number of trees in 2020 was 56, standing for the 50 states, Washington, D.C., Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and American Samoa.

Traditionally, each tree is uniquely decorated by students from the state or territory that the tree represents. In 2020, however, due to restrictions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, students instead drew designs for their decorations and submitted them to the National Parks Service, who printed them out and hung them on each of the trees. Since 2008, the Pathway of Peace has also included Santa's Workshop, sharing cheer and safety tips with those on their way to the Community Tree.

Pressing a button isn't as easy as it seems

The original intent at the very core of the National Christmas Tree lighting was for the American people to see the President of the United States lighting up thousands of electric lights on his Christmas tree and therefore be convinced that electric lights on Christmas trees were cool. And while the tradition of the president hitting the button has been more or less the thing since the 1920s, it hasn't always gone without a hitch, nor has it always been what you might expect. In 1924, for example, as the National Parks Service explains, Coolidge threw a switch instead of hitting a button, the only year that ever happened. However, from 1931 until 1980 it's notable that the button the president pushed was not actually connected to electricity: hitting the button only signaled someone else who sent power to the lights.

In 1934, Franklin Roosevelt hit the button only for the lights not to come on at all for about five seconds of awkward silence as the president looked around in a mild panic. Between 1948 and 1951, Harry Truman spent Christmas at his home in Missouri, and so on those years he symbolically lit the tree via remote control, a technique used again in 1955 when Dwight Eisenhower was recovering from a heart attack. Ronald Reagan also lit the tree remotely from 1981 to 1983 for fear of assassination attempts.

The National Christmas Tree that almost wasn't

While the lighting of the National Christmas Tree has occasionally experienced hiccups in terms of electrical problems or just a soupçon of viral pandemic, no year has experienced more tree trouble than 1970. According to the National Parks Service, the tree that year was a massive 78-foot cut spruce from the Black Hills of South Dakota. It had, suffice it to say, one heck of a time getting to Washington, D.C. The train carrying the enormous tree derailed not once, but twice, and both times in the same state: Nebraska. Get it together, Nebraska. The tree hardly fared better once it arrived in Washington. The weekend before the lighting ceremony, gusts from a windstorm toppled the tree, which broke several branches that had to be cut and replaced with branches from another tree to fill it out.

Still, the tree managed to get decorated and lit. It had 5,000 blue and green bulbs, as well as somewhere between 750 and 900 yellow bulbs. The topper was a teardrop-shaped wire sculpture containing a bulb inside it. Sounds very nice. The bad news is that the electrical sockets for those nearly 6,000 bulbs had been coated with a liquid fireproofing spray which was causing shorts in the strings of lights. As a result, the bulbs on the lower half of the tree began to explode. Whoops.

Protests at the tree lighting

While the lighting of the National Christmas Tree is often seen as a time to promote community spirit, peace, and goodwill, it hasn't always been the site of universal holiday cheer. In fact, since the 1960s, protesters have used the popularity and visibility of the event as a chance to make their voices heard. In 1969, about 200 anti-war protesters heckled Richard Nixon during his brief remarks, and eight adults and one teen were arrested for disorderly conduct. Hornbake Library records that at the 1971 lighting, demonstrators, including members of the group Vietnam Veterans Against the War, interrupted Vice President Spiro Agnew's lighting ceremony remarks by shouting "Peace now!" The Washington Post relates that in 1981 protesters included supporters of the Equal Rights Amendment and those condemning Reagan's budget cuts to aid for the poor.

In 1980, the president himself used the tree to make a political statement. Jimmy Carter and his young grandson lit the tree, but the lights only stayed on for 417 seconds, one second for each of the days that the American hostages in Iran had been held captive up to that point. After that, the tree remained unlit except for the star, which had been placed on the tree by the wife of the highest-ranking hostage at the embassy. Once the hostages were released on January 20, the tree was quickly decorated in time for their return home.

Legal battles over the Pageant of Peace

The celebration of Christmas as a national community event is a controversial choice. Obviously, Christmas is–despite many layers of secular sheen painted over it–a religious holiday at its core, and not everyone is part of that religion, despite what your uncle might say on Facebook.

The National Parks Service records that the first legal challenge to the National Christmas Tree, and more specifically the Pageant of Peace and its very large Nativity, came in 1968. This challenge was brought by the American Civil Liberties Union, who invoked the First Amendment, saying that having a giant statue of the baby Jesus in front of the president's house sure seems a lot like government sponsorship of one particular religion. While the Parks Service argued that the symbols of the Nativity and the tree were not strictly religious, they nevertheless gave up the responsibility of constructing or maintaining the Nativity scene, which was given to a private organization.

The following year, the ACLU was joined by the American Jewish Congress in suing that private organization. The U.S. State Court of Appeals dismissed the case, saying that no one was forced to look at the baby Jesus. This decision was reversed in 1971, when the District Court discontinued any involvement of the Parks Service in the sponsorship of a Nativity scene. Nevertheless, despite challenges, a Nativity continues to be a part of the pageant.