What Life As An Egyptian Royal Was Really Like

Over the thousands of years that separates ancient Egypt from the modern world, there have been quite a few myths about its people and their achievements. According to History Extra, things that are considered hallmarks of Egyptian history, like gigantic pyramids, were centuries out of fashion by the New Kingdom era in 1550 B.C.E. Egyptian people were also rather progressive for their time, with more or less equal rights for women and men, as well as the beginnings of labor unions and organized workers' protests, History reports. Then again, it's fair to say that there was some hierarchy to their society, given how much effort went into propping up the Egyptian royal family.

Perhaps, knowing all of this, it's not surprising to learn that the life of ancient Egyptian royalty wasn't all that easy or simple. They definitely enjoyed plenty of perks, from fancy foods to fine clothing, but their lives also included seemingly endless meetings, daily temple rituals, and the occasional assassination plot. Even the pharaoh, who was widely considered to be at least a semi-divine descendant of the Egyptian gods, experienced a complicated, often demanding life.

Egyptian royals were never alone

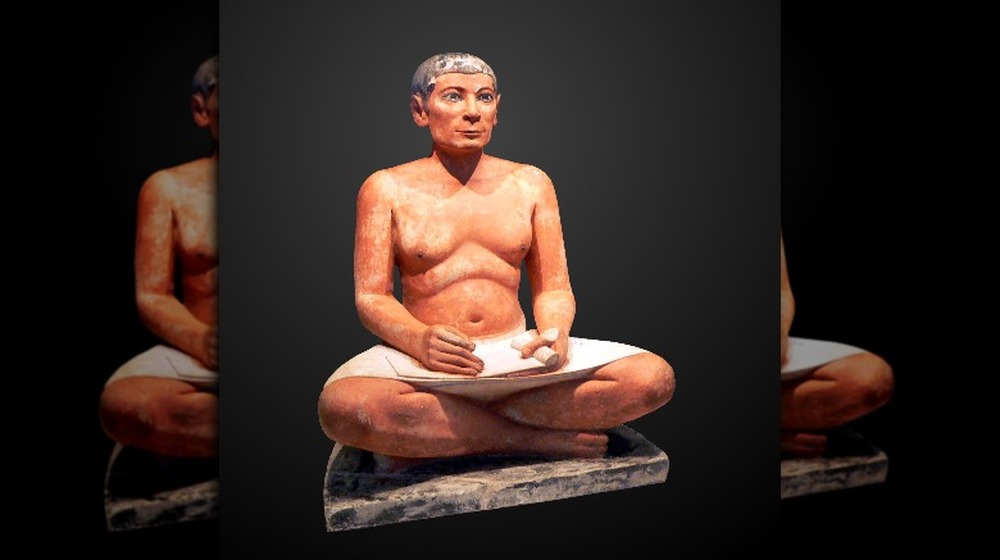

Hopefully, members of ancient Egypt's royal family never longed for a simple moment by themselves. They would have never gotten one. According to The Pharaoh's Court, the king would have had his own extensive personal staff who managed his affairs but also hounded him with questions and opinions. There was the steward, who ran the royal estates, the chamberlain of the palace, and many scribes, craftspeople, military generals, and money managers, to name a few.

Then, there were the servants. No royal retinue could appear as well-coiffed and impressive as they did without an army of retainers. Daily Life of the Ancient Egyptians notes that they would have been with the king from his first waking moments, cleaning and dressing the royal body with the utmost care. Other members of the royal family, including primary wives and heirs, would have enjoyed similar perks. These included an official sandal bearer, multiple wig preparers, a chief clothes washer, bodyguards, fan bearers, and much more. Even the people who did the king's nails were a big deal, In Bed With the Ancient Egyptians reports. The Fifth Dynasty overseers of manicurists in question, Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum, had enough prestige and capital to build a lovely tomb together.

Dressing the ancient Egyptian royal body took time and money

While lower class folks might expect to wear simple clothes made out of coarsely spun linen, royals would have been garbed in far finer stuff. However, their finely made clothes and jewels took considerable effort just to get them on the royal bodies.

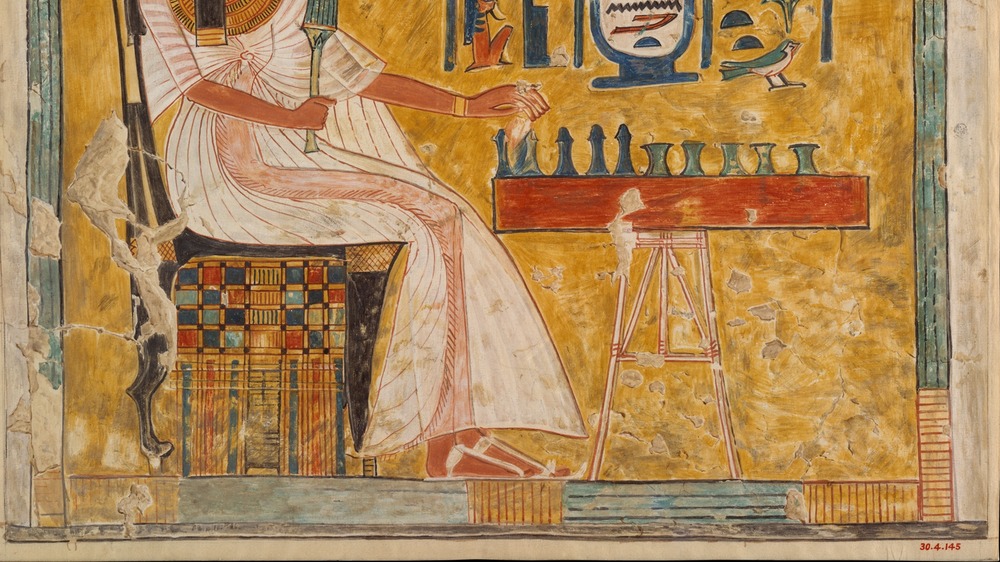

According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, the general form of ancient Egyptian clothing was relatively simple, with kilts for men and a long shift dress for women. The higher up in class one went, the finer the fabric was and the more it was weighed down with ornamentation. By the time you get to the royal household, members of any gender would have been bedecked in finery. These eventually included sandals, which would have been an almost exclusively upper-class luxury. Tutankhamun's tomb was packed with over 90 pairs of footwear, including one set made of gold.

One of the most elaborate parts of a royal Egyptian's kit would have been their wig. Worn by both men and women, hairpieces would have been another feature of upper-class and royal looks, Internet Archaeology reports. Some would have gotten so large and complicated that the weight of wearing one could have worn bald spots into people's scalps, assuming they hadn't shaved their hair already. The process of constructing and maintaining these wigs was so involved that it formed its own cottage industry, including the servants who would have helped members of the royal household don the heavy, decorated rugs.

Royals got the best foods in ancient Egypt

For ancient Egyptians of the lower classes, food was generally a simple and sometimes pretty restricted affair. BBC's History Extra reports that commoners weren't so bad off, however, as they enjoyed harvests from the banks of the Nile, which were enriched by yearly flooding. Agricultural products included plenty of wheat, vegetables like onions, leeks, lettuce, and beans, as well as a variety of fruit. Hunters and fishermen brought in animal protein, while some were even able to keep domesticated animals like sheep, pigs, and geese.

There was still a significant class divide when it came to the dinner table. According to History, more humble folk generally stuck to a rather monotonous spread of bread, fish, beans, and onion, usually with home-brewed beer. Royals, however, were given a far richer and more varied diet. Going off of details like tomb paintings and carvings, archaeologists know that they dined on delicacies like honey-roasted gazelle, rare fruits like pomegranates, and sweet cakes. Meat and dairy appears to have been a regular staple of their diet, unlike commoners. Instead of cloudy beer, members of the king's household were more likely to drink fine wines, delivered by servant girls lugging around entire jugs of the stuff.

Diplomacy and administration dominated the Egyptian royal schedule

The rich food and fine clothing were undoubtedly luxuries that ancient Egyptian royals enjoyed, but their position came with a price. Some days, pharaohs were doomed to back-to-back meetings. This was long before the advent of coffee, remember, and so the king and his attendants had to suffer through administrative duties uncaffeinated.

It wasn't as if the king had to take on all of this alone, however. According to Daily Life of the Ancient Egyptians, the country boasted a highly organized government. Local affairs were taken care of by regional officials. Still, PBS says, the king was supposed to handle much of the higher level national and international affairs, like speaking with military generals and communicating with ambassadors.

It wasn't as if the pharaoh could really cancel a meeting or two. According to the Ancient Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, the law demanded that the king had to tackle these tasks, no matter how boring. "All their acts were regulated by prescriptions set forth in the laws," he wrote. "And the hours of both the day and night were laid out according to a plan, and at the specified hours it was absolutely required of the king that he should do what the laws stipulated and not what he thought best." These intense duties included receiving administrative documents and letters pretty much as soon as he rolled out of bed, so he could get right to work before even getting dressed.

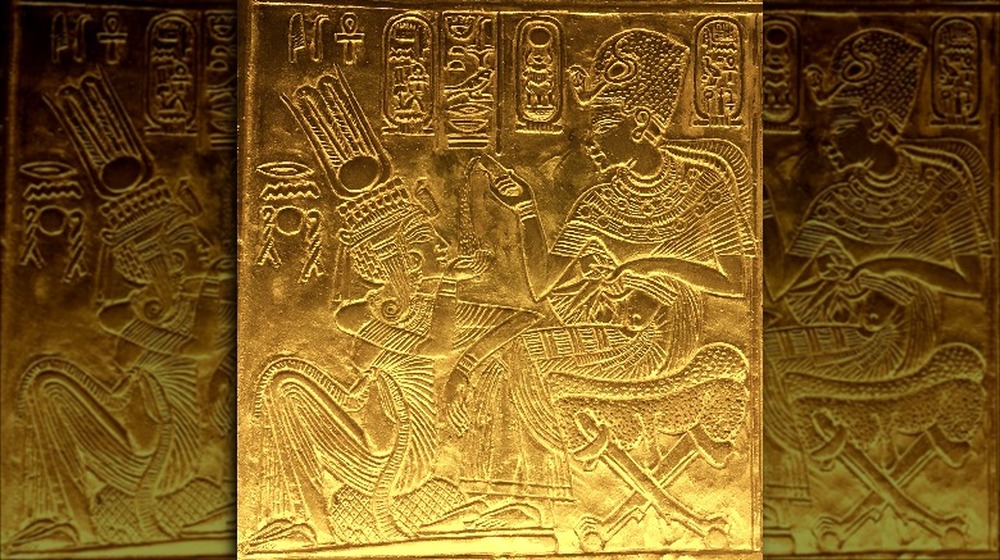

Egyptian royal marriages got complicated

The love life of a pharaoh in ancient Egypt could get wickedly complex. According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, infidelity was generally frowned upon amongst commoners, accompanied by tales of cheaters meeting their doom after it was discovered that they had been stepping out on their spouse. Yet, as happens throughout history, it was different for rich people. Kings and other royal men were able to marry as many women as they could support. Indeed, pharaohs were widely known to keep harems of women in addition to their wives. This subset of the royal household could include foreign princesses with hefty dowries, though, as Daughters of Isis reports, Egyptian rulers were very reluctant to let their own daughters marry into foreign courts.

Royal matches could also get alarmingly close. As per National Geographic, sibling or even parent-child marriages weren't unheard of for ancient Egyptian rulers. That level of inbreeding eventually led to dire consequences. Tutankhamun, the pharaoh whose parents were closely related and who may have been married to his own half-sister, appears to have suffered from a variety of ailments that could be linked to his overlapping genetic heritage. History reports that examinations of his mummy revealed he had a serious foot deformity, buck teeth, and a painful bone disorder known as Kohler disease. Tut would almost certainly have needed a cane or other assistance just to walk around the royal palace.

Ancient Egyptian royals spent a lot of time in the temple

Though given the constant meetings and building projects, it may seem as if the pharaohs were basically trumped-up upper management types, their roles in Egyptian society had a more mystical side. According to PBS, they were generally regarded as divine or at least semi-divine beings, though it's not known whether individuals bought into the god king rhetoric. As a godly being, the pharaoh had to pay regular tribute to the big gods, especially the chief deity, Amun-Re. This included prayer and animal sacrifice, which were considered necessary less the whole kingdom descend into chaos.

The daily visits to temples also meant that the pharaoh had to deal with one of the most powerful groups in ancient Egypt — the priesthood. Throughout the kingdom's history, the Ancient History Encyclopedia says, priests and priestesses were so influential that their position sometimes rivaled that of the royals themselves. Without their religious devotion, it was thought that the kingdom would fall apart and the spirits of previous royals doomed to obscurity in the afterlife. Some royals even got in on the game, like the post of God's Wife of Amun based in Thebes. Originally, this was an honorary position with little real meaning. Over the centuries, it evolved into an ultra-powerful post that allowed some women, many of whom were kings' daughters, to effectively rule half of Egypt from the Theban Temple of Karnak.

Egyptian royal family members were more likely to get murdered

Ancient Egyptian royals might have been chowing down on fancy feasts like honey-roasted gazelle while bedecked in the finest linens and jewels, but they may have been distracted from such finery by very real danger. They weren't even fearing the pure boredom of endless meetings or repetitive temple rituals. No, members of the royal family had to consider the very real possibility that someone might want to murder them.

Such are the risks of dealing in power. Some kings and queens were just fine, but quite a few met untimely deaths at the end of an assassin's knife. For Ramesses III, the murder was coming from inside the house. According to National Geographic, he was the victim of the Harem Conspiracy, wherein members of his royal harem planned to assassinate Ramesses and his heir, then install another son on the throne. It appears that they were semi-successful, as Ramesses' mummy has a horrific throat wound that would have certainly killed him. The conspirators didn't make it to the heir, however, and surviving papyrus fragments show that many of them were executed after a trial.

Another pharaoh, Seqenenre Tao, met an even more violent end via massive head trauma, according to the Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. It's very possible that Seqenenre died on the battlefield, given that his remains were hastily embalmed, perhaps because his forces were far from home.

The pharaoh's health wasn't the best

Being an Egyptian royal meant that one enjoyed a life of leisure. They were carried about on sedan chairs, dressed by servants, and given the finest foods available. However, the flip side of this lazing about held some very serious health consequences.

Inbreeding, which pharaohs sometimes used to keep the throne in the family, could backfire terribly. Generations of occasional sister-brother marriages seem to have reached their unfortunate peak in Tutankhamun. According to Smithsonian Magazine, the boy-king was so affected by genetic disorders and a malformed foot that he couldn't have walked unaided.

Even if they had a more diverse genetic background, royals suffered from their cosseted lifestyle. Hatshepsut, the female pharaoh who ruled Egypt in the 15th century B.C.E., apparently dealt with serious health issues because of her sedentary existence and rich diet. According to LiveScience, her presumed mummy shows signs of obesity and diabetes.

Hatshepsut's woes didn't stop there. History reports that she also suffered from arthritis and a genetic skin issue that could have caused awful itching. Her mummy was found with an expensive skin cream that would have soothed her skin but was also packed full of a cancer-causing tar. A CT scan of her mummy later indicated that she had died of bone cancer, perhaps caused by continued use of that high class, carcinogenic cream.

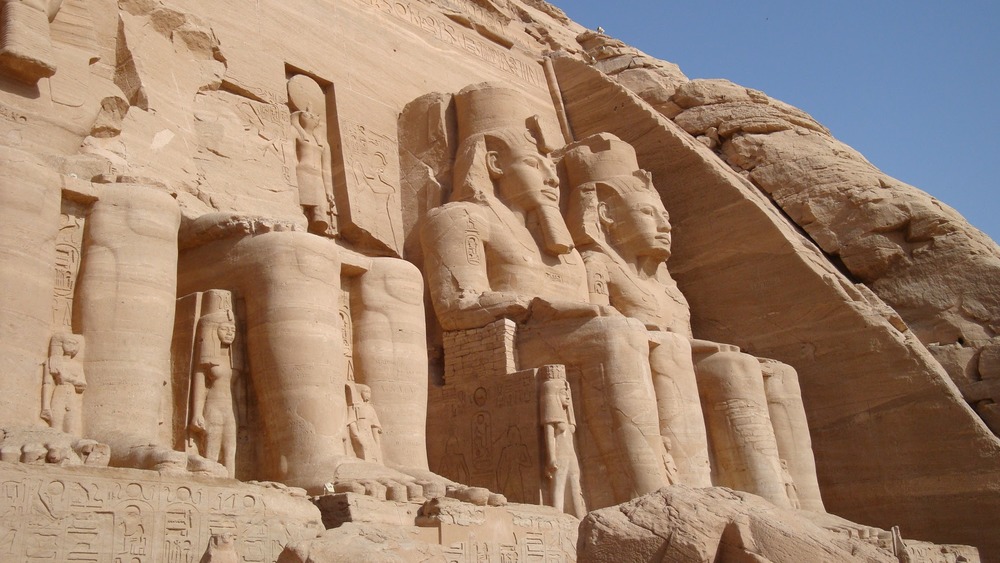

Royal Egyptians were really into construction projects

Like many big names of the modern era, ancient Egyptian royals loved to helm building projects throughout the land. Having your name and graven image on the side of an eye-catching temple does much to hold up your propaganda machine. According to Britannica, Ramses II earned his title of "Ramses the Great" largely through his massive building program that threw up construction projects throughout the kingdom, with his image and accompanying hype-man style text on practically every surface. He even built a namesake residence city, Per Ramessu, that acted as a capital and center for his famous military exploits.

The adoration of never-ending construction got so serious that an architect named Imhotep was eventually worshipped as a god. No, this was not the villainous Imhotep of The Mummy movie franchise but an ancient genius who laid the intellectual and engineering foundation for the Great Pyramids of Giza. Though he did not mastermind those particular pyramids, the Ancient History Encyclopedia reports that he did design the Step Pyramid of pharaoh Djoser, which set the stage for later developments. He was also Djoser's vizier, a priest, a poet, doctor, scientist, and mathematician. Around the year 525 B.C.E., long after his death in 2600 B.C.E., Egyptians deified him, adding yet another accolade to this ancient Egyptian overachiever's long list of accomplishments.

Royal women had real power in ancient Egypt

Unlike in other societies of the time, women in ancient Egypt held considerable power, the Ancient History Encyclopedia reports. From the peasants all the way up to the royals, women were regularly treated as equals to men, though it's also clear that some traditional pathways to power were frequently blocked for women.

For royal women, however, it was a bit easier to wield political power approaching that of their male fellows. According to National Geographic, sometimes this went all the way to the top, as a few notable women became power queens and even pharaohs in their own right. These include famous names like Cleopatra, Nefertiti, and Hatshepsut, says History Extra, along with less well known though just as influential women like Sobeknefru and Khentkawes I.

Even if a royal woman didn't actually get to sit on the throne or right behind it, they could still be deep in the political game. As per the Ancient History Encyclopedia, the priestess known as the God's Wife of Amun was so powerful that even the pharaoh had to think carefully before interacting with her. This woman, working from the Temple of Karnak at Thebes, an important religious center, was no one to mess with. The position started off as a nearly meaningless ceremonial title that, over the centuries, evolved into a role so powerful that, by 750 B.C.E., Amenirdis I used it to effectively rule half the kingdom.

Egyptian royals sometimes went rogue

Sometimes, the power and religious responsibility that came with being pharaoh caused some rulers to go pretty wild. One took his status as a deity so seriously that he became a heretic whose infamy has lasted for thousands of years.

When Amenhotep IV took the throne around 1390 B.C.E., National Geographic reports, things looked normal at first. Then, about five years into the reign, the king flipped everything upside down. He was now to be addressed as Akhenaten, he told everyone, and they were going to abandon the old gods and worship just one, the sun deity Aten. A new capital was built, then called Akhetaten and now known as Amarna. Art styles changed dramatically, with the carved images uncovered in Amarna showing the royal family with fluid, elongated bodies. His queen, Nefertiti, was named co-regent.

An estimated 30,000 people moved to Amarna, but, 17 years later, Akhenaten was dead, and it was all over. The city was abandoned, the heretic pharaoh was dissed, his imaged chipped off monuments, and the old gods welcomed back into royal life. They weren't completely successful, however. After more than 3,000 years, according to Oxford Handbooks Online, excavations in the 19th and 20th centuries C.E. uncovered Amarna and the tale of its heretic king.

Royal tombs of ancient Egypt were too fancy for their own good

Some of the royals probably thought they'd enjoy a nice time in the afterlife while their remains rested in a tomb. Unfortunately, all of the nice things packed into flashy burial places also attracted grave robbers. This wasn't a sporadic thing, either. According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, tomb robbing was an extensive, ongoing issue in ancient Egypt. Even the Great Pyramids, those famous structures on the Giza plateau just outside of modern-day Cairo, were raided not long after the pharaohs inside were deposited there. Curses carved into the stone of the pyramids, specifically directed at tomb robbers, weren't enough. Even the mummies of the supposedly divine kings have gone missing over the intervening millennia.

Eventually, it became clear to ancient folks that these huge tombs brought way too much attention. National Geographic writes that their solution was to hide all of the upper class mummies and their riches in a remote desert valley. Known today as the Valley of the Kings, the hidden entrances to the royal tombs there clearly weren't concealed very well at all. Records from Egyptian history show that robbers were sometimes caught in the valley and given harsh punishments. By the 20th century, the vast majority of burial places had already been picked over. The boy king Tutankhamun's tomb, discovered by archaeologist Howard Carter in 1922, was one of a very few exceptions.