Tragic Details About Comedy Legend Ernie Kovacs

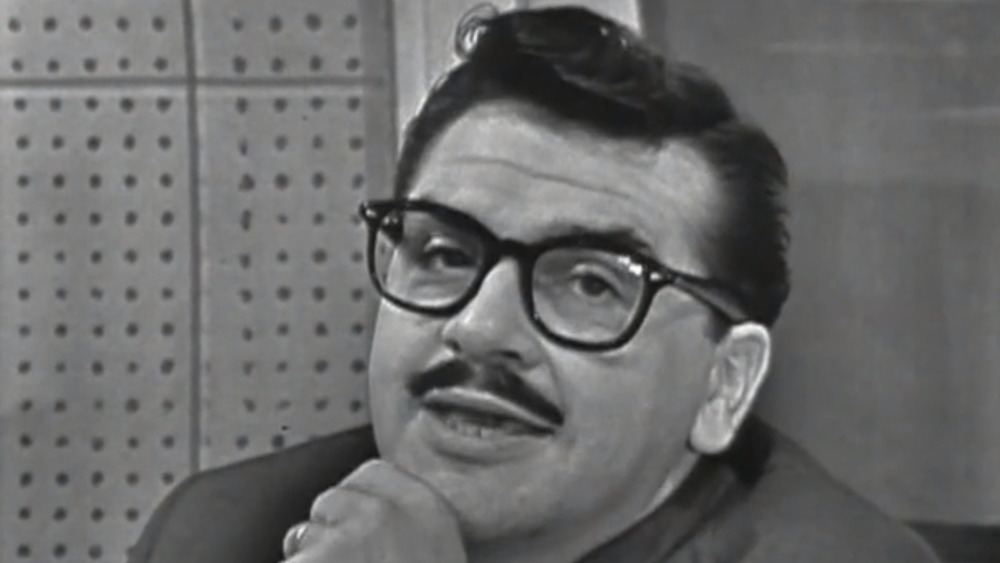

During television's celebrated golden age, Ernie Kovacs was to comedy what Rod Serling was to drama. Although his name may not be as familiar as 1950s legends such as Lucille Ball, Sid Caesar, or Jackie Gleason, Ernie Kovacs' impact is immeasurable, if not largely unsung. His quirky sensibilities and penchant for absurdity have influenced generations of comics ranging from Great Britain's legendary Monty Python troupe to talk show giant David Letterman. Kovacs, with his lightning fast wit and spontaneity, revolutionized comedy for television, stripping it of its vaudeville roots and re-inventing it for a new medium and a new generation.

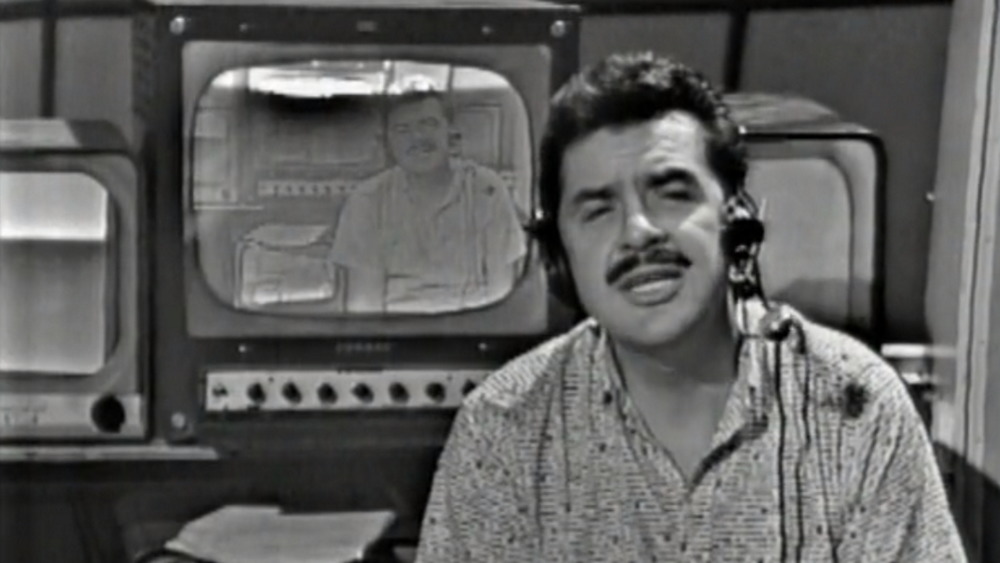

Long before the 60s, Kovacs was bringing video art and outlandish, proto-psychedelic imagery to television audiences. A visual innovator, he used the tools of TV production as never before. In Kovacs' hands, video could be as abstract and fluid as music. Through his unique camera work and trickery, the image on the screen took on life and meaning of its own beyond merely conveying a picture to the audience.

Yet, much of Kovacs' life was anything but mirth and merriment. Debt, a failed marriage, and a heartbreaking battle for the custody of his children mired him in depression and desperation. Sadly, an car accident would take Kovacs' life at the age of 42. Although critics and fellow comedians praised him, it would take decades for audiences to realize the full scope of his importance. Read on to discover the tragic details of Ernie Kovacs' incredible life.

Ernie Kovacs' childhood is a riches to rags story

Ernest Edward Kovacs was born on Jan. 23, 1919, in Trenton, N.J. His father, Andrew Kovacs, immigrated from Hungary at age 13. Discovering that crime did indeed pay, the elder Kovacs, a heavy-set man with a big personality, left his job as a foot patrolman to become a bootlegger during prohibition. With his connections at city hall and Trenton's unquenchable thirst for illegal hooch, Andy Kovacs got rich quick and moved his seamstress wife Mary and sons Tom and Ernie to a 20-room mansion on the affluent side of the city.

Mary Kovacs doted on young Ernie. According to The Ernie Kovacs Phile (originally published as Nothing in Moderation: A Biography of Ernie Kovacs), by David G, Walley, Mary Kovacs liked to dress little Ernie like a dandy, outfitting the youngster in a black-velvet Little Lord Fauntleroy suit of her own creation, to the jeers of his friends. "It was like walking around with a sign that said 'kick me,'" Ernie Kovacs remembered. "I would come running home with ten guys chasing me."

The Kovacses' fortunes took a devastating blow in 1933. With the repeal of prohibition, liquor was once again legal and easily obtainable, and Andrew Kovacs was out of a job. A failed attempt to enter the restaurant business met with more financial ruin for the Kovacses. With the restaurant's collapse, Andrew and Mary's marriage would also come crashing down. With their finances in the red, the Kovacses sold their house and withdrew Ernie from private school.

Ernie Kovacs was a high school slacker

As a privileged child attending Miss Bowen's Private School, young Ernie Kovacs thrived. An intelligent and inquisitive child, he excelled in his studies. To keep the precocious Kovacs challenged, he was allowed to skip two grades.

The family's economic downturn abruptly ended Kovacs' private school days. Entering public high school as a junior, teenage Kovacs lost interest in his studies. Slated to graduate from Trenton Central High in 1936, Kovacs, who was quickly gaining a reputation as a class clown, was held back for a semester because of his poor grades.

Fortunately, Kovacs' interest in theater and singing in the school chorus gave the indifferent student a sense of purpose. He found a mentor who shaped his direction and instilled the confidence that was a hallmark of Kovacs' personality. Drama teacher Harold Van Kirk recognized Kovacs possessed a talent beyond that of his high school peers. With Van Kirk's help, Kovacs won a full scholarship to John Drew Memorial Theater in Long Island, N.Y. The budding actor threw himself into his craft taking on roles large and small during his summer at John Drew. As detailed in The Ernie Kovacs Phile, Van Kirk coached Kovacs through his first bad review in which a critic called him "a ham." "All that remark shows is that critics aren't as smart as they should be," Van Kirk stated. Remembering his prize student, Van Kirk recalled, "Ernie never overacted. His personality was such that he overpowered everybody, even in a small part."

Ernie Kovacs struggled with poverty

Following his summer semester at the John Drew Memorial Theater, Ernie Kovacs won a scholarship to New York's American Academy of the Dramatic Arts. Although Kovacs was no stranger to poverty while at John Drew, frequently losing his pay in post-curtain poker games, New York presented a new level of destitution. Prior to moving to the city, Kovacs' situation was lean but livable. Life in New York turned out to be a daily fight to stave off hunger.

Moving into a $4-a-week room in a fifth floor walkup on West 74th Street, Kovacs was so poor that scrounging up money to buy a loaf of bread was nearly an insurmountable challenge. When dry bread became unbearable, and he wanted a hot meal, Kovacs would mash the bread in hot water to make a pasty, homemade gruel. When he could afford it, Kovacs would take in a cheap, quick meal of a peanut-butter-and-cream-cheese sandwich and a cup of coffee at fast food emporium Nedick's. On occasion, Kovacs would starve himself for a few days for a 35 cent splurge on a plate of spaghetti and a movie at a crosstown second run cinema. "Usually, it was The Life of Beethoven," Kovaks recalled years later. "I saw that seven times."

Kovacs' living conditions weren't much better than his diet. Largely oblivious to the goings on in his crime-ridden neighborhood, he was shocked when his landlady and her daughters were busted for running a brothel one floor under his apartment.

Ernie Kovacs nearly died of tuberculosis

Ernie Kovacs' impoverished lifestyle took a toll on the aspiring drama student's health. During his second year at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, Kovacs was frequently ill. While working in Vermont during the summer of 1939, Kovacs was stricken with pleurisy, a painful condition in which the tissues of the lungs and chest cavity become inflamed. Exacerbating his condition, Kovacs also developed a case of pneumonia. Malnourished and fatigued, Kovacs collapsed.

Unable to breathe, let alone work, Kovacs found himself in a dire predicament. His parents had separated, leaving the young actor with no home to which he could return. Confined to a terminal hospital ward on New York's Welfare Island (now known as Roosevelt Island), Kovacs' health was further compromised when he contracted tuberculosis. Although Kovacs would jokingly refer to this period of convalescence as the "Welfare Island Engagement," his condition was so serious that doctors did not expect him to survive.

As recounted in The Ernie Kovacs Phile, the comedian was placed in an open ward with nearly a hundred other moribund patients. As beds emptied, Kovacs noticed hammering sounds from outside, which he assumed was construction work. However, when he was placed near a window, he discovered the noise was workmen building coffins.

Despite the seriousness of his condition, Kovacs kept the medical staff entertained with practical jokes. After 18 months in the hospital, a bored Kovacs determined that he was well enough to leave. Without being officially discharged, Kovacs gathered his belongings and left.

NBC ended Ernie Kovacs' successful morning show

With the United States' entry into World War II after Pearl Harbor, Ernie Kovacs was eager to join the fight. Unfortunately, his weak lungs would keep from military service. Instead, he would serve on the homefront as an announcer on Trenton radio station WTTM. His ability to liven up broadcasts with his hilarious improvisations made him a hit with audiences.

After nine years at WTTM, Kovacs left radio. Seeing his future in television, he departed Trenton for Philadelphia. Taking a job hosting a pair of cooking shows on NBC affiliate WPTZ, Kovacs brought his wit and absurdist comic sensibilities to TV for the first time in 1950. Thanks to Kovacs' taste for the surreal, Deadline for Dinner and Now You're Cooking wouldn't be typical cooking programs.

In November 1950, WPTZ placed Kovacs as host of Three to Get Ready. The first regularly scheduled morning program in a major television market, Three to Get Ready beat NBC's Today to the air by a year. A hit with viewers, the show gave Kovacs free rein to run wild with his most irreverent and original ideas from hurling eggs at the camera to bizarre gags with an oversized rag doll affectionately known as Dirty Gertie. Audience reaction was overwhelmingly positive, and WPTZ opted to air Kovacs' show instead of the network's The Today Show, which had been created based on Three to Get Ready's success. Nevertheless, WPTZ caved to network pressure and ended Three to Get Ready to air NBC's morning show.

Ernie Kovacs' unique style cost him work

Not everyone appreciated Ernie Kovacs' absurdist ad-libbing and flair for the bizarre. On occasion, his inability to take anything seriously landed him in hot water with the powers that be. Nevertheless, Kovacs played by his own rules regardless of the consequences.

After several short-lived but popular shows at CBS and the Dumont Network, including Kovacs Unlimited and The Ernie Kovacs Show, NBC lured Kovacs back with a $1 million exclusive contract. One of his first jobs after returning to NBC was filling in for his late night rival Steve Allen on Tonight. When the network tapped Allen to host a Sunday night variety show to compete head-to-head with CBS' The Ed Sullivan Show, Kovacs would host on Monday and Tuesday nights. "I said you could use Ernie Kovacs or Jack Paar. . .," Allen stated in an interview for a 1998 episode of Biography. "And they tried both guys, but Ernie was quite an individual because he didn't come out of nightclubs. He wasn't a stand up [comedy] guy."

Kovacs was far more interested in pushing TV technology to its limits to perfect his unique visual brand of laughs. The comedian's love of long improvisational bits also tended to cut into commercial time, drawing the ire of sponsors. According to the 1982 documentary Ernie Kovacs: Television's Original Genius, one NBC executive bemoaned Kovacs' "lack of discipline." When Allen departed Tonight for good in 1957, the hosting slot went to Jack Paar.

Taxes and gambling wrecked Ernie Kovacs' finances

Aside from making people laugh, Ernie Kovacs' greatest obsession in life was gambling. According to biographer David Walley, Kovacs' passion for betting extended well beyond cards. The comedian could make nearly any activity an opportunity to make or lose a buck. Kovacs was known to play Monopoly with real money and would bet on each point of a friendly tennis match.

Kovacs began playing poker as a drama student at the John Drew Memorial Theater, where he regularly lost his entire week's pay in post-curtain games with the more seasoned actors and crew. At the height of his career, Kovacs made cards a scheduled part of his daily routine. Throughout his life, he preferred traveling by train over flying simply because a meandering ride on the rails provided enough time for a few hands of gin rummy.

Unfortunately, gambling and his well-paying career in TV and film failed to cover his lavish lifestyle. Kovacs spent with abandon. Not wanting to worry his wife Edie Adams and his children, he hid the extent of his debt.

Kovacs' precarious financial situation worsened in 1961 when the IRS came calling. Owing half a million dollars in back taxes, Kovacs battled to have the sum reduced but refused to pay the government the money they said he owed. "He spent what he got which is why he never wanted to pay taxes," Kovacs' friend, actor Jack Lemmon, told Biography. "He thought that was totally unjust and ridiculous so he just didn't do it."

Ernie Kovacs' failed first marriage

In 1945, Ernie Kovacs met Bette Lee Wilcox at a USO show at Trenton's Hotel Hildebrecht. Smitten with the brunette dancer, Kovacs asked Wilcox to marry him after a brief courtship. Considering his meager finances and an admitted lack of maturity on Kovacs' part, the marriage was tumultuous at best. Temporarily moving in with Kovacs' mother was a disaster for everyone. Wilcox and Mary Kovacs fought constantly over finances with Ernie caught in the middle.

Despite the constant arguments and alleged infidelity on Wilcox's part, the union produced two daughters, Betty and Kippie. The girls were the center of Ernie's life and his sole source of happiness in a rapidly deteriorating marriage. Originally from Florida, Wilcox would take the girls on extended vacations to Daytona Beach leaving Ernie alone for weeks or months at a time.

Later, Wilcox came to resent giving up her career for motherhood and retreated into an inner life brooding over her failed dreams. She left Kippie and Betty unattended for hours. "My father had to run home from the radio show he was doing, and, during the break, take care of me because I wasn't being taken care of," Kippie Kovacs told Biography in 1998.

In 1949, Wilcox abandoned Ernie, leaving him to care for the children on his own. For a while, he struggled bravely, shuttling between work and home to change diapers and prepare meals when he couldn't find babysitters. Finally, he enlisted the aid of his mother. Nevertheless, Wilcox would soon return to bring even more chaos to Ernie's life.

Ernie Kovacs' ex-wife kidnapped his daughters

Just as Ernie Kovacs was becoming a television star, his estranged wife returned to lay claim to his money and his children. By November 1951, Kovacs was caught in the throes of a bitter fight for custody of his two daughters. The court eventually granted full custody to Kovacs citing Bette Wilcox's mental instability.

On July 19, 1952, Kovacs turned his daughters, Betty, age 3, and Kippie, 1, over to their mother for their pre-arranged, Sunday visit. On the following Monday, Kovacs' uncle arrived at Wilcox' residence to pick up the girls. To his shock, he found Kovacs' daughters, Wilcox, her mother, and stepfather had disappeared. The next day, the police attempted to apprehend Wilcox's stepfather, Sydney Shotwell, for the kidnapping. Shotwell escaped after a harrowing car chase with police. Facing a grand jury indictment for kidnapping, Shotwell and the Wilcoxes fled to Florida with Kovacs' children.

Kovacs spent $50,000 on private detectives and initiated a nationwide search for his daughters. At last, in 1955, Betty and Kippie Kovacs were located in Jacksonville, Fla., in a shack located behind a restaurant where Wilcox was employed as a waitress.

Ernie Kovacs was a hit with critics but a flop in the ratings

As detailed by the Museum of Broadcast Communications, Ernie Kovacs' had a number of shows spanning all four major networks during a brief period in the 1950s. This fact is a testament to both Kovacs' success as an artist and failure as a TV host. Although programmers recognized Kovacs' genius, they were unable to rein him into a format that viewers and, more importantly, sponsors, would respond to. Critics praised Kovacs as an innovator, while TV audiences more accustomed to the vaudeville-inspired style of comics such as Sid Caesar and Milton Berle never watched in great enough numbers to make Kovacs a hit.

Despite Kovacs' legendary appetite for luxury, his work was never strictly about money, and it certainly wasn't about ratings. ". . . Ernie wouldn't compromise," Kovacs' friend and photographer Bob Kemp told David Walley. "It didn't matter what the network thought. It didn't matter what the people at home thought. He had to do it his way. And he did it great."

A tragic auto accident claimed Ernie Kovacs' life at age 42

Ernie Kovacs spent the evening of Jan. 12, 1962, at a party at director Billy Wilder's Beverly Hills apartment. The gathering was ostensibly a baby shower for Milton Berle and his wife who had just adopted a newborn baby. In attendance were many of the biggest celebrities of the day. Kovacs, who had worked nonstop the previous week on a pilot for a Western comedy and his seventh TV special, would spend most of the evening enjoying cards and drinks with his friends Jack Lemmon, Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, and Joey Bishop.

The party broke up at one in the morning. Kovacs sent his wife and comedy partner Edie Adams home in their Rolls Royce. The comedian, fatigued from overwork and lack of sleep, would take their Corvair station wagon. Losing control of the car on rain-slicked pavement, Kovacs collided with a power pole. He was killed instantly, just 10 days before his 43rd birthday.

Ernie Kovacs remains an unsung comedy hero

More than half a century since his death, Ernie Kovacs remains a cult figure mostly unappreciated by the mainstream. A beloved comedy hero to a small, but dedicated following, Kovacs' avant-garde brand of absurdist, visual comedy never fully connected with audiences of his time.

The next generation of comedians and comedy writers, however, got the joke. Rowan and Martin, Terry Gilliam of Monty Python, David Letterman, Conan O'Brien, and countless other performers credit Kovacs as an influence. Chevy Chase, who would thank the late comedian for his 1976 SNL Emmy win, explained Kovacs' appeal to documentarian Keith Burns. "We thought he was magnificent," Chase said. "This was around the era of Milton Berle, who we didn't watch at all — we thought that was sort of cheap, easy, vaudeville television. . . [Kovacs] had a way with that cigar and that cheeky smile. . . which said, 'I'm not going to hurt you, but, boy, this going to be fun.'"