Things The Da Vinci Code Gets Right About Religion

When it was first published in 2003, The Da Vinci Code was an immediate hit. It's easy to understand why. Dan Brown's novel contains a dramatic story in which professor Robert Langdon gets caught up in an ancient conspiracy, concealed beneath many layers of mystery, that claims Jesus Christ and Mary Magdalene produced a "holy bloodline" that lives to this very day. Plus, there are murderous monks.

While readers were eating it up, historians cringed. Much of the story is entirely fictional, though Brown repeatedly claimed that he drew upon genuine fact. In a 2003 interview with CNN, he even claimed that "99 percent of it is true," including the novel's lurid tales of secret societies like the Priory of Sion and Opus Dei. In the years since, however, few of the claims between the covers of The Da Vinci Code have been definitively verified.

Yet, as much as it's been derided, The Da Vinci Code occasionally gets things right. Sure, oftentimes you'll need to approach some of its claims sideways to find a hint of reality, but that genuine history is there nonetheless. Certainly, Brown's claim that the history of Christianity is more complex and divisive than many people realize is very true indeed.

The Da Vinci Code is right about early Christians arguing all the time

One of the biggest things The Da Vinci Code gets right about religion is the fact that, for many years, no one could agree on what the "Bible" was supposed to be.

According to History, the first known attempt to create a canon happened in second-century Rome. However, Marcion, who tried to assemble the Gospel of Luke and Paul's letters into a single document, riled up church leaders so badly that he got expelled. The Muratorian Canon, one of the closest things to the modern New Testament, was probably collected in the third century. It wasn't until the fifth century C.E. that most Christian churches finally agreed on a Biblical canon, nearly 500 years after the crucifixion of Christ.

The fourth and fifth centuries were especially turbulent for the church, Britannica reports. In the 300s, there was Arianism, which claimed that the human Jesus couldn't be one and the same as God, causing the Council of Nicaea to work itself into a frenzy. Questions over the exact nature of Christ also led to the Christology controversy in the 400s. Essentially, Christology, which came in different variations and intensities, pushed the still very controversial idea that the human Jesus wasn't as fully divine as others in the church wanted him to be. Even today, different denominations of Christianity are still busy arguing over doctrinal differences, much like their religious forebears.

The Gnostic Gospels make the history of the Bible and The Da Vinci Code complicated

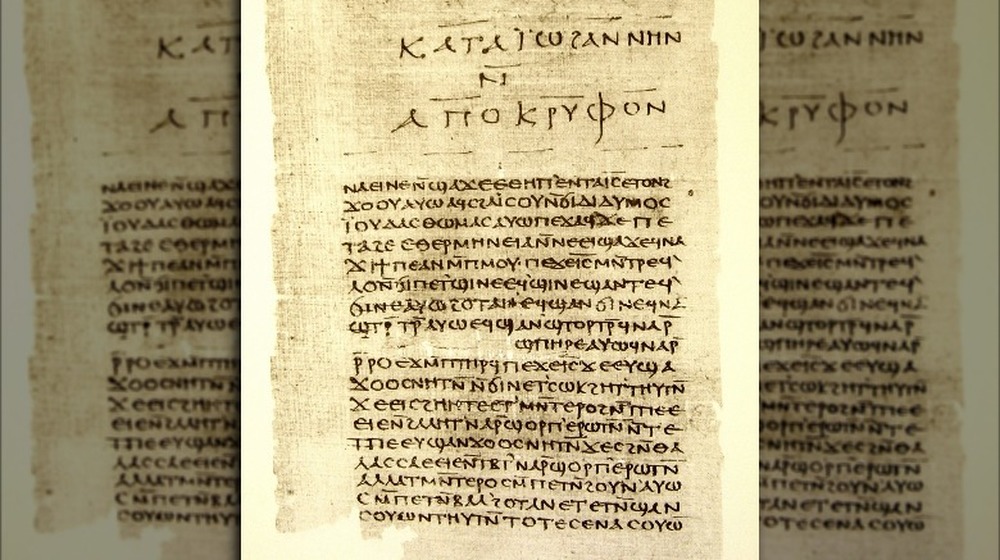

The Gnostic Gospels have been causing trouble for a long time, but they only came to modern attention within the past century. Frontline reports that these 52 texts were discovered in Nag Hammadi, Egypt, in late 1945. Muhammad 'Alí al-Sammán later said that he and his brothers were digging for soil to use with their crops. Muhammad 'Alí al-Sammán uncovered a clay jar and, thinking that it might contain valuable treasure, smashed it open. Instead, he found 13 leather-bound papyrus documents.

Ultimately, some of the documents made it to Cairo, where researchers soon began to investigate the texts. Professor Gilles Quispel traveled to Cairo's Coptic Museum, where he began to translate the fragile papyri. The first line he deciphered shockingly referred to Jesus' "twin," Judas Thomas. Another, the Gospel of Philip, reads like an extended edition of the sayings of Jesus.

The texts uncovered by Muhammad 'Alí al-Sammán were actually translations of even older works that were about 1,500 years old. They would have been buried near Nag Hammadi because church authorities were already suppressing work they deemed unfit by the second century. According to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, these early heretical Christians were called Gnostics from "gnosis," Greek for "knowledge." Broadly speaking, many Gnostics believed that spiritual knowledge had to come from within one's self, rather than from the church. It's easy to see how religious leaders would have wanted to squash independently minded Gnosticism.

Mary Magdalene was a problematic figure for early Church leaders

As one of the few confirmed female followers of Christ, Mary Magdalene stands out in the canonical Bible. However, as the BBC points out, many modern readers and believers have confused Mary with an unidentified sex worker who also interacts with Jesus in the New Testament. In fact, though she makes an appearance in each of the four gospels, no text explicitly states that she was even a known sinner. Still, for many years, Christian churches have combined the characters of Mary Magdalene, the unknown sex worker, and a third woman who washed Jesus' feet with her hair. In the sixth century, Pope Gregory the Great officially claimed that these three figures were all the same woman, leading to even greater confusion. The Catholic Church didn't walk back this statement until 1969.

Even without the rumors of a romantic relationship with Jesus, Time reports, Mary Magdalene's spiritual importance has proven controversial for many Christian leaders. Some of the Gnostic gospels even describe her as the only disciple who really gets Jesus and his message. That makes things pretty awkward for Peter, the apostle who was said to have helped found the Christian church after Jesus' crucifixion. It was more awkward still for the male church leaders who followed, which is perhaps why some of the writings more complimentary to Mary Magdalene were conveniently left out of the Bible.

Mary Magdalene's gospels get more complicated than The Da Vinci Code

As PBS reports, the Gospel of Mary is a controversial Gnostic gospel that singles Mary out for special status, similar to Dan Brown's depiction of her in the novel. In one fragment, Peter addresses Mary Magdalene directly after the Resurrection, saying, "Sister, we know that the Saviour loved you more than the rest of women."

When Mary goes on to describe the vision she had of a post-Resurrection Jesus, Peter appears to grow sour at this point. "Did He really speak with a woman without our knowledge [and] not openly?" Peter asks. "Are we to turn about and all listen to her? Did He Prefer her to us?" Other disciples come to Mary Magdalene's defense, saying she must be special if Jesus singled her out.

However, the Gospel of Mary Magdalene doesn't say she's anyone's wife. That's the job of the even more contentious bit of parchment known as "The Gospel of Jesus's Wife," though, as The Atlantic reports, scholars aren't sure it's genuine. The fragment, written in Coptic, contains the phrase, "Jesus said to them, 'my wife.'" Yet, as many have pointed out, the fragment may have been intentionally cut, as if more context would show that Jesus wasn't referring to a literal spouse. Furthermore, it's possible that the fragment's owner, a German immigrant named Walter Fritz, may have forged it, either to make some money or even bring The Da Vinci Code into reality.

Some scholars think Mary Magdalene's relationship with Jesus was unusually close

Within the canonical Bible, there's nothing that says Mary Magdalene and Jesus were married and had children, no matter how much The Da Vinci Code may want you to believe in hidden symbols and metatextual analysis. There's nothing definitive that says their relationship was anything more than a teacher and dedicated follower. Then again, some of the non-canonical gospels tantalizingly hint at a complicated relationship between the two.

There are some texts that raise eyebrows even amongst the most conservative Biblical scholars who, presumably, torch a copy of The Da Vinci Code every night for fun. In the Gnostic, or non-canonical, Gospel of Philip, reports NPR, there's a line that says Mary Magdalene received a kiss from Jesus. Yet, just before readers can learn exactly what kind of kiss it was, the text is cut off by the crumbling paper.

The Gospel of Philip also indicates that the other disciples were jealous of all that kissing, platonic or otherwise, as it essentially marked Mary Magdalene as teacher's pet. Introduction to the Synoptic Gospels admits that this certainly appears to show that Mary had a special insight into Jesus' teachings that wasn't available to the other disciples. This view is supported by other textual evidence in the Gospel of Mary and the Gospel of Thomas, two other non-canonical texts you won't find in most Bibles today.

The Priory of Sion was kind of real but not ancient history

The Da Vinci Code will have you believe that the Priory of Sion is a shadowy organization formed centuries ago to keep the secret of the "holy bloodline" established by Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and their children. Dan Brown based his novel on the much-criticized 1982 book, The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, which claimed that the priory was the real deal. In fact, the similarities between the books were so striking that the authors of The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail sued Brown for copyright infringement, though The Guardian reports that they lost the case in 2006.

So much for the fight amongst authors, but what about the Priory of Sion? Could it have been real after all? In short, no. The priory was a hoax that first cropped up in the 1950s, though some documents led incautious researchers to think that the organization was founded in the 12th century. According to CBS, the perpetrator of the fraud was a French man named Pierre Plantard who claimed to have been a Grand Master of the Priory of Sion. He set up the organization in 1956 and apparently forged historic documents to establish a better pedigree for his venture. Real clues, like the use of text from an 1889 version of the Bible in supposedly ancient writings, made it clear that the Priory of Sion was nothing more than an elaborate ruse.

Opus Dei is a real Catholic organization

Unlike the fictitious Priory of Sion, the organization known as Opus Dei really does exist. However, while The Da Vinci Code paints the group as a collective of ominous priests, the reality is a bit more mundane. As per NPR, Opus Dei was founded in 1928 and now has thousands of lay members (or non-clergy) in numerous countries. The core ideal of Opus Dei is to implement conservative Christian values in their members' lives and communities. The devotion to the cause has gotten so intense, sometimes, that outsiders have accused the group of getting overly political and pretty culty.

This means that Opus Dei has encountered its fair share of controversy over the years, Britannica reports. Members have been involved in Francisco Franco's dictatorial Spanish government from the 1950s to the 1970s, starting decades of questions about members' involvement with various international governments. Others point to brainwashing tactics used on new recruits, secret memberships, isolation from non-affiliated family members, and Opus Dei's unquestioning embrace of Catholic theology as indicators of its possible cult status. However, Opus Dei naturally hasn't admitted to being a cult and still enjoys support from the Vatican.

Some believers say Mary Magdalene really went to Europe

The Da Vinci Code implies that Mary Magdalene eventually leaves Jerusalem and makes it to Europe. It doesn't get too into the weeds of how, exactly, Mary or at least her bones made it to a new continent, but the novel ends with protagonist Robert Langdon praying before her hidden sarcophagus. The Louvre in Paris denies that Mary Magdalene's remains are somewhere in or around its Pyramide inversée skylight, as The Da Vinci Code claims. Coincidentally, the Louvre says that the inverted pyramid is actually inside an underground shopping mall, instead of in the museum proper.

Yet, there is a tiny bit of truth to the idea that Mary made it to France. Those looking for definitive proof will be disappointed, however. Instead, we must turn to folklore. National Geographic reports that southern France hosts a cave shrine to her based on the tradition that she either crossed the Mediterranean or else trekked across Europe sometime after the crucifixion. One town, Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mar, claims to have been the site where all three biblical Marys arrived by boat after the crucifixion, according to The Independent.

Whether that was part of her post-Resurrection life as a wanderer, as some traditions claim, or whether she was hauling some divine kids alongside her is left up to individual interpretation. Though there's no concrete evidence supporting this claim, enough believers have flocked to her shrine over the centuries to keep the mysterious and compelling story alive.

There is something to The Da Vinci Code's ideas about the sacred feminine

Though most historians agree that Dan Brown really overstated the matter, The Da Vinci Code skirts pretty close to the truth when it starts to discuss the sacred feminine. The early Christian church especially seemed occasionally unafraid to venerate female figures in its history. As The Real History Behind the Da Vinci Code points out, the church generated an almost immediate tradition of venerating the Virgin Mary that persists to this day. It's likely no coincidence that Mary, Mother of God, and a bevy of other female saints took over sites that had previously been dedicated to non-Christian deities. In a similar vein, later philosophers would feminize Christian-adjacent concepts like the virtues, nature, and nurture.

Meanwhile, Gnosticism developed its own approach to the sacred feminine. Gnostic texts often refer to Sophia, defined by the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy as the concept of wisdom and also a feminine aspect of God. In some interpretations, Sophia commits an act of hubris when she wishes to stand apart and create on her own, leading to separation from the Godhead and a powerful desire for reintegration. In a more positive light, the divine "sparks" of Sophia's wisdom and creativity are also aspects of a larger divinity. Virgin Mother Goddesses of Antiquity argues that Sophia is also connected to earlier female deities and the concept of wisdom and order so central to Gnostic practices.

Early saints hint that women had a much more powerful role in Christianity's past

Female Christian saints have always been part of the religion, but the stories of early Christian saints indicate that maybe, despite all of the fretting over Mary Magdalene in the Gnostic gospels, women held real power in the new faith. Consider Saint Thecla. According to the Biblical Archaeology Society, she was said to have been a noblewoman who was so taken by the preaching of Paul, one of Jesus' disciples, that she immediately converted to Christianity. Under Paul's advice, she became celibate and dumped her fiancé.

Thecla's family didn't take kindly to her new faith and tried to burn her on a bonfire. She survived and left town, following Paul and repeatedly defying death, before settling down and becoming a religious teacher in her own right. As the apocryphal Acts of Paul and Thecla claim, a 90-year-old Thecla finally makes it to paradise while avoiding yet another mob. During the chase, God opens up a rock and commands her to walk inside. The rock closes up behind her, leaving behind an astonished crowd.

Thecla's story was complemented by that of Perpetua. According to Britannica, Perpetua left behind a journal documenting her impending martyrdom in a Roman arena in 203 C.E. This document, recounting much of Perpetua's story in her own words, gives voice to one of the venerated female saints who, in many ways, embodied the divine feminine so central to Dan Brown's novel.

The Da Vinci Code gets religious artwork kind of right

Much of the plot of The Da Vinci Code hinges on messages supposedly hidden in the midst of great artworks, like Leonardo Da Vinci's legendary fresco, The Last Supper. While practically no serious scholar believes that these artworks are part of an elaborate treasure hunt that will lead the seeker to a sarcophagus full of Mary Magdalene's bones, the art referenced in Dan Brown's novel is rich with religious symbolism.

To that end, the Musée du Louvre offers a roundup of some of the artworks featured in the 2003 novel and its 2006 film adaptation. Though the museum states that it rather scrupulously won't take sides for or against the story, some interpretations are pretty clear. The idea that Mary Magdalene is buried beneath the Inverted Pyramid is "entirely fictional," according to the Louvre. However, works like Veronese's The Wedding Feast at Cana are rich with symbolism that would make Robert Langdon drool. Does the Virgin Mary appear to be holding an invisible glass because she's really in charge of an unattainable Holy Grail? Another painting, Bronzino's Noli Me Tangere, depicts Mary Magdalene's encounter with the resurrected Jesus. She can't touch him, but the art does indeed display a certain kind of physicality that perhaps inspired Dan Brown's more romantic interpretation of their relationship.