What It Was Really Like To Party Like An Ancient Roman

The Ancient Romans are famous for a number of things: their vast imperial conquests, their art and architecture, and a huge body of literature by writers such as Vergil, Cicero, Ovid, and Horace. They also have a reputation in modern times for their excesses in feasting and drinking. The Roman elite are not entirely unfairly cast as gluttonous, hedonistic debauchees who would drink and eat rich foods until they threw up and then eat some more.

But how much of this is fact and how much is fiction? Were these splendiferous bacchanals simply empty pleasure, or was there something more to them? More importantly, what is the wildest party ever thrown by a Roman emperor? To find out how to party like a Caesar, or at least like an upwardly mobile former slave with nontraditional tastes, dump some snow in your wine, sew some goose wings onto a roasted pig, and read on.

The Roman party venue and guests

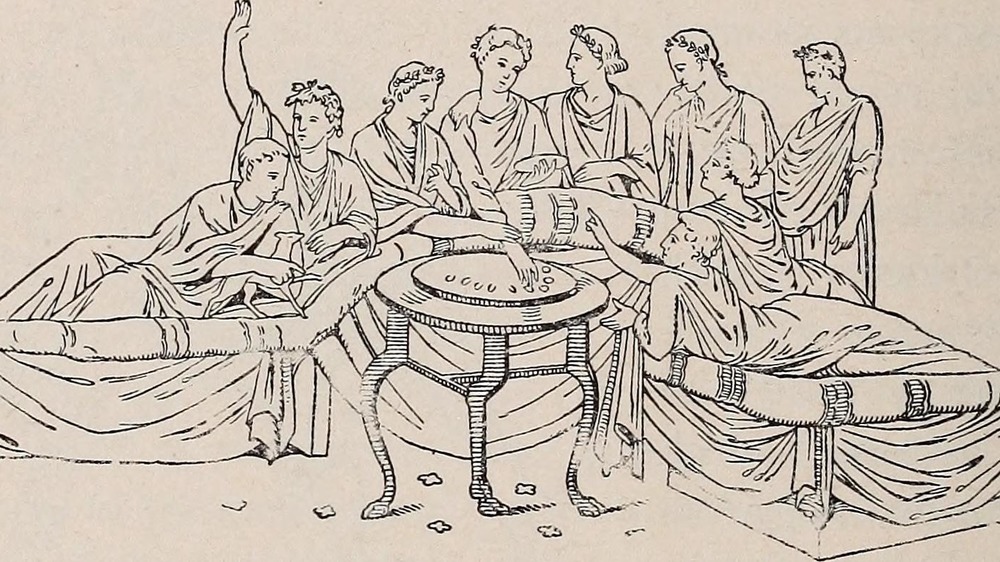

As opposed to larger public festivals, the Roman dinner party known as the convivium generally took place in a private home. As the Metropolitan Museum of Art explains, these dinner parties were held in residences with attendance from a small group of friends, family, and business associates, though they were still designed to be extravagant and impressive. The most common reception room for such parties was the dining area, which in Roman homes were known as the triclinium, or "three-couch room," because dining was typically done while reclining on couches, which were arranged in a U-shape with a table in the middle in order to facilitate sharing and conversation. As these entertaining spaces were meant to be a delight to the senses, an upper-class triclinium would often have many decorative elements such as floor mosaics, sculptures or other pieces of art, and fancy furniture.

While the Greeks were known to enjoy drinking parties known as symposia (the one at which Socrates and friends discussed the true nature of love being the most famous one), Roman dinner parties were different in a number of ways. The chief difference is that women were allowed to attend Roman parties, providing that they were of the appropriate class. At Greek symposia, the only women allowed were entertainers, musicians, or sex workers known as hetairai. If you were Roman, at least your wife could be there.

Party as power play

While a normal person might throw a party to celebrate an anniversary or major life accomplishment, or even just to hang out with friends, for aristocratic Romans–especially political figures like the emperor–lavish banquets were essential political tools for garnering favor and accumulating power. According to NPR, these extravagant dinner parties were a way for Rome's elite to show off their wealth, network with the powerful, and intimidate their enemies. These ulterior motives were even more important for emperors, who were able to display their power, offer gifts to those who might bestow upon them political favor, and keep an eye on their political rivals.

And also sometimes political assassinations were on the menu. While actual evidence of poisoning at parties is rare, Roman dignitaries always got suspicious when someone took sick after a party. A notable example is when the son of the emperor Claudius died after a party and suspicion naturally fell on Nero, who stood to benefit most from the death of Claudius' heir (Nero did end up succeeded Claudius as emperor, and we all know how that went). For the most part, however, the goal of such lavish banquets was not political murder but rather buying favor with a swell time. The satirical Roman poet Juvenal cynically–but accurately–summed up the imperial means of distracting the citizenry from issues with food and entertainment as "bread and circuses."

The all-important seating chart

Since the goal of a Roman banquet was often political or business-oriented in nature, it makes sense that the seating chart would be an essential aspect of preparation. High-powered guests could be flattered with a seat of honor, while the host could secure himself unfettered access to an influential guest during dinner. The Getty Museum explains that the three couches of the Roman triclinium represented different tiers of respect. The most honored guests would recline on the couch that formed the center of the U-shape, while the host would lie to their right. Less important guests would lie on the leftmost couch, somewhat ironically known as the lectus summus, or "high couch."

By seating the guests of honor on the middle couch, the host assured not only that these guests would be the center of attention for anyone entering the room, but they also made sure that these important diners got the best view during the party, typically of the host's courtyard or garden. The low-status guests would have to settle for staring at the dining room's expensive and extravagant wall art. Or their food or the other guests, maybe. As time went on, parties got bigger and more elaborate, so hosts needed more than just the traditional nine-person, three-couch style. These couches were replaced by a huge semi-circular couch called a stibadium that could hold up to 12 people.

Don't forget the wine

Besides the fact that women were allowed to be guests, another thing that distinguished the Roman convivium from the Greek symposium was that wine was drunk through every stage of a Roman party. This is somewhat ironic as the word symposium literally means "drinking together," but the wine part of a symposium was usually saved for after dinner. It was generally considered gauche by both Greeks and Romans to drink wine that had not been mixed with water, so, as the Metropolitan Museum of Art explains, at dinner parties, each guest's wine would be mixed with water to taste in their individual cups (Greeks, meanwhile, usually mixed the wine in a communal mixing bowl called a krater). Wine was served into the drinking cup with a ladle, which allowed for exact measurements, by attractive, often nude, male slaves. Depending on the party, hot or cold water would then be mixed in. The Romans used special boilers called authepsae to heat their mixing water. If a host really wanted to show off, they might add snow to the wine.

The cups of the Roman elite were typically made of silver, and while there are multiple types of cups in the archeological record, the most common types were two-handled cups modeled off the Greek style. More ornate cups were decorated with reliefs depicting floral motifs, erotic scenes, or mythological subjects, including of course Bacchus, the god of wine.

Food as spectacle

A typical Roman banquet was made up of three courses: the hors d'oeuvres, the main course, and dessert. And as most dinner parties were meant to impress, the food was generally a spectacle designed to engage all of the senses and present something never seen before. As the Met explains, exotic foods were common, as their rarity, high cost, and difficulty in acquiring were a part of the appeal, showing the wealth, taste, and tenacity of the host. Popular dishes included oysters, wild boar, venison, pheasant, lobsters and other shellfish, peacock, and basically any kind of songbird you can imagine. Foods that were actually illegal for being too fancy, such as sow's udders and fattened up poultry, were common at these elite affairs.

A Roman author named Apicius recorded in the only extant cookbook from the Roman empire hundreds of recipes that include such outlandish dishes as parrot, goose liver, camel heels, flamingo, cranes, ostrich, coxcombs, sausages stuffed with brains, crawfish stuffed with caviar, and snails, which were eaten so commonly that there were actually special spoons made just for eating snails. There are also recipes for normal stuff like vegetables and beans, but who cares about that in the face of honey-smeared nightingales stuffed with prunes, as Apicius was said to have served to the emperor Tiberius' sons? Anyway, Apicius spent all his money on fancy food and killed himself when he went bankrupt.

Dinner with a side of deathsport

Parties aren't just for eating and drinking, they're also about having a good time. As such, Roman banquets were often the place for all sorts of entertainment, some of which we might even consider deranged or unsafe today. The Met explains that while the food and wine were meant to stimulate the palate, the entertainment was designed to delight the eye and ear. A very common element at dinner parties was musical accompaniment in the form of flutes, water organs, lyres, or even choirs. If your party mood is a little less "adults enjoying wine and cheese" and a little more hype, you might hire the services of acrobats, dancing girls, or mimes. If you want the party to get really lit, you might bring in trained exotic animals or have a gladiatorial battle, in case you're as thirsty for blood as you are for wine. Chiller options include having poetry readings or recitations of history. The cheapest option might just be having your slaves sing as they serve the food and wine.

NPR relates one notorious–and probably apocryphal–example of party entertainment gone too far. The famously extravagant emperor Elagabalus wanted to shower his dinner guests with flowers, so he built a dining hall with a false ceiling that was then filled them. When the ceiling was tilted open, a flood of petals fell heavily upon the guests and smothered them to death.

The vomitorium wasn't a thing

While Roman dinner parties are infamous for their excess–with NPR quoting a professor who says that "Romans ate to the point of vomiting" at their "hedonistic banquets"–at least one aspect of them has been exaggerated in modern culture. Scientific American says that it is a common belief in popular culture that the Romans had a special room called the vomitorium where they would go during dinner parties in order to purge their bellies so that they could make room to indulge in more food. Modern authors as different as Aldous Huxley and Suzanne Collins have often discussed the vomitorium as a literal place in the home as a symbol of Roman excess, indulgence, and disgusting luxury.

There was not, in fact, a dedicated boot-and-rally room in Roman homes. "Vomitorium" was a word in classical Latin, possibly coined by the writer Macrobius. He wasn't talking about a puke room, though. He was describing the entrances and exits at stadiums and theaters, which resemble someone throwing up in the way that people poured out of them and into the streets or seats. It was a weird, kind of intentionally gross metaphor. But sometime in the 19th century, people started taking the word literally and applied it to their pre-existing notion of the Romans as an indulgent and gluttonous people. In this case, truth is less strange than the legend.

Feasting the gods

While the Roman convivium was a private and even exclusive affair, it was not the only kind of dinner party to be found in ancient Rome. As History and Archaeology Online explains, an epulum was a public feast with a religious, rather than social or political, end. As opposed to the private convivia, epulae were civic banquets open to all the citizens of the city and frequently played host to enormous numbers of diners. When the epulum had a specific religious focus, food offerings were made to the gods who were generally present in the form of statues.

One of the most notable of these public religious feasts was the Epulum Jovis, or Feast of Jupiter. This feast was celebrated every September 13, the Ides of September, and was originally held for the dedication of the temple on the Capitoline Hill, which was dedicated to Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva, the gods known as the Capitoline Triad. Seven priests whose job was overseeing the public feasts would sacrifice a white heifer and then invite the gods to feast. Statues of the gods were placed on couches bedecked with the most splendid of coverings, an act known as lectisternium. While initially only the Capitoline Triad took part in this feast, by the third century BCE, all 12 Olympian gods were present in the form of statues chilling on couches.

Christmas before Christ

There was no shortage of Roman holidays, with some state holiday, religious feast, or public games being held practically every other day on the Roman calendar, celebrating everything from fertility to driving out the shades of the evil dead. But as History points out, the most popular Roman religious festival–and the one probably best known to modern readers–was Saturnalia, the midwinter festival celebrating Saturn, the Roman god of agriculture, who was thought to have overseen a Golden Age of former generations of humankind. By the late Republic, Saturnalia had expanded from a single-day festival to a weeklong affair stretching from December 17 to 25, and its influence is thought to still be felt in modern Christmas celebrations.

Saturnalia represented an upending of standard social order. Businesses and schools closed, work was forbidden, and slaves and masters traded places. Well, kind of. Masters would serve their slaves, who would sit at the head of the table and take part in the holiday festivities. Houses would be decorated with wreaths and greenery, and colorful clothes were worn. Gambling was temporarily legalized, and singing, feasting, socializing, and gift-giving were standard celebrations. A common Saturnalia gift was candles, which represented the return of sunlight after the winter solstice. Houses would elect a leader of Saturnalia, a Lord of Misrule, to oversee the chaos represented by this joyous, raucous, topsy-turvy time.

The orgiastic rites of Bacchus

Even today, the word bacchanalia is used to refer to a riotous drunken party, often aimed at boisterous fraternity or sorority parties. This reputation for bacchanalia goes back to ancient times as well. You can probably put together that a bacchanal is a celebration of the god Bacchus, known also as Dionysus, the Greco-Roman god of wine and fertility. As the Encyclopedia Britannica explains, the Roman bacchanalia were based on the various Greek rites known as Dionysia, which, depending on location, could include drunken feasts, ritual parades, dramatic performances, or carrying clusters of grapes around.

These Greek fertility rituals were introduced to Rome through Greek provinces in southern Italy. The Italian bacchanalia were initially celebrated only by women and were held three times a year, during the day. However, before long, men were admitted as well, and the rites were held at night, as often as five times a month. The rituals were private, and like most ancient mystery cults, we don't actually have much information about them. What we do know is that men and women getting together in big groups at night to drink wine and party caused a huge scandal among the Romans. Rumors that the bacchanalia included orgies and even human sacrifices led to the Senate passing a ban on bacchanalia throughout all of Italy in 186 BCE. Despite this decree, bacchanalia continued covertly in southern Italy for many years.

Caligula's party barge

From a modern perspective, Roman emperors have a reputation as pampered libertines, like Nero lying on a couch and being fed grapes while the city burns around him. This wasn't true of all Roman leaders: NPR points out that Julius Caesar, his heir Augustus, and Stoic philosopher-king Marcus Aurelius were all famous for their simple diets and moderation. However, the reputation for debauchery was earned by some, like Elagabalus, who swam in a saffron swimming pool and served his guests rice mixed with pearls. But probably the most famously debauched Roman emperor of them all was Gaius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, better known by his nickname, "Little Boots," or Caligula.

According to History, Caligula is known even today for his wild fits of spendthrift waste and capricious violence. He was enormously egotistical, wanton, and hedonistic. His personal and financial excess led to his being assassinated after four years on the throne, the first (but hardly last) Roman emperor to be assassinated. But before that, he would hold his violently orgiastic parties on luxury barges described as being "blazed with jewels" and "filled with ample baths, galleries, and saloons, and supplied with a great variety of vines and fruit trees." These boats were deliberately sunk after Caligula's assassination, and researchers have been trying to find them for the last several decades, after some of Caligula's other ships were discovered in the 1920s.

The most famous Roman party of all

There are a number of specific parties from the Roman era that have gained notoriety. One of these, related by NPR, was the emperor Domitian's black banquet, at which he draped his hall in black and had all the food dyed black before seating all of his guests next to tombstones with their names on them. He spent the whole feast in a dark mood, talking about murder and death. The guests, worried that they would never escape with their lives, would later find out this was all a morbid prank. The most famous Roman party of all time, though, is a fictional one. This is the Cena Trimalchionis, or dinner of Trimalchio, the largest episode of the first century CE novel Satyricon, by Gaius Petronius.

As the Encyclopedia Britannica explains, Trimalchio is a freed slave who has become fabulously rich, and the bulk of the satire in this section is about the vulgarity of the nouveau riche. The excess of Trimalchio's dinner party is meant to be almost grotesque, with its description of a hare with wings affixed to look like Pegasus, cooked fish made to look like they were racing in sauce, and foods made up to resemble the signs of the zodiac. Another notable fact is that when Trimalchio goes to the bathroom, one of his guests tells one of the earliest werewolf stories in all of literature.