The Messed Up History Of The First Persian Empire

Which empire was the greatest of all time? Chances are you might think of the Romans first, or maybe the Mongols if you prefer a slightly deeper historical cut. If you restrict your criteria to just be about the physically largest empire of all time, you might consider, again, Rome, to which all roads led, or maybe even the more modern British Empire, on whom the sun famously never set. It turns out, in fact, that arguably the most powerful empire of all time was none of those but rather the first Persian Empire, also known as the Achaemenid Empire, which rose to power under Cyrus II, known as the King of Kings.

The Achaemenids became famous for both their beneficence and religious tolerance as well as their hideous cruelty. Can both of these be true, or is one side just propaganda from their political enemies? Read on to learn the horrible truth.

Becoming the King of Kings

In the sixth century BCE, the Persians went from being a small vassal state to the largest empire the world had ever seen up until that point. As the Ancient History Encyclopedia explains, at the time, the people who would come to be known as the Achaemenids were the rulers of a small city in the mountains of Iran known as Anshan. The first major imperial power in the Iranian peninsula was the Medes, who, together with the Babylonians, had played a central role in the previous ruling power of the area, the Assyrian Empire. Around 550 BCE, the son of the Persian king Cambyses I decided he wasn't interested in serving the Medes anymore. He led a successful revolt against Media, taking control of the capital and claiming the empire for himself. Before long, this son of Cambyses would be known as Cyrus the Great, and his dynasty, the first Persian Empire, would be known as the Achaemenids, after one of Cyrus' ancestors, Achaemenes.

After taking control of the Median Empire, Cyrus began a systematic campaign of conquests across the lands east of the Mediterranean, including Lydia in Asia Minor and Babylon. The Achaemenid Empire stretched from Libya to India, from the Black Sea down to Kush. At its greatest extent, it encompassed over two million square miles and held over 40 percent of the world's population.

The benevolence of tyrants

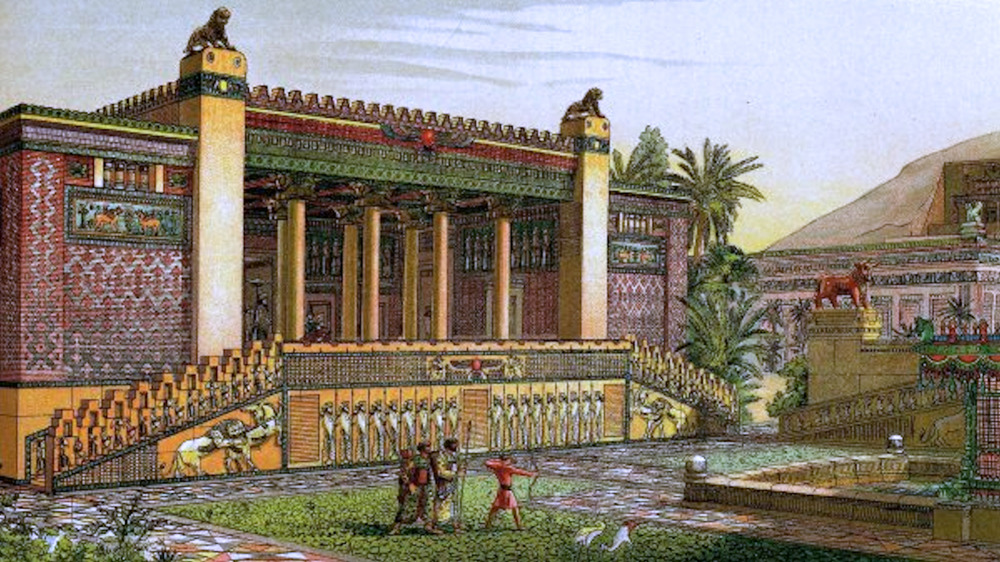

We have very little about the culture of the Achaemenid Empire from their own point of view: Pretty much everything we know about them comes from their enemies, the Greeks, who painted them as a frequently cruel, bloodthirsty, and rapacious people. However, the first Achaemenid emperor, Cyrus the Great, is unique not only among Persians but indeed all world conquerors in the depth of his humanity and beneficence. According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, a record of the Achaemenid king's policies and works are recorded on an artifact known as the Cyrus Cylinder, which tells of not only his public works projects and humanitarian efforts but also his vision of his empire as a place where everyone was free to live as they wished as long as they kept peace with their neighbors.

One of his major acts of beneficence for his conquered lands was to foster technological innovations to aid his people. Much of the land appropriated by the Persians had little access to water. To counteract this, Cyrus had his engineers develop an old Assyrian technique for bringing water from underground aquifers known as qanats to the surface. Cyrus also developed early refrigerators, founded a postal system that was so fast and efficient that even the Greek historian Herodotus had to proclaim it a wonder, and built a garden so nice that its name is the literal source of our word "paradise."

The complex bureaucracy of the Achaemenids

The problem with having the largest empire in history is that it can be difficult to rule geographically spread out and ethnically diverse people from a single, centralized capital. As a result, the Ancient History Encyclopedia says that Cyrus II instituted a hierarchical bureaucracy in which the different regions of the first Persian Empire would be administered by local governors known as satraps. Satraps were only granted the ability to tend to administrative matters, while a military commander would be left in each province to deal with military and peacekeeping matters. This bureaucratic division was intended to keep any one single provincial leader from amassing the wealth or influence necessary to try to stage a revolt against the empire. This method had the additional benefit of making lands conquered by the Persians feel as if not much had actually changed following their conquest, as they were still governed by local leaders. All of this contributed to the sustained stability of the Achaemenid Empire.

ThoughtCo records that the Persian king Darius I reported the list of Achaemenid satrapies during his rule (at which point the empire was at its peak) in an autobiographical document known as the Behistun Inscription. According to Darius, the provinces under his command included Babylonia, Assyria, Arabia, Egypt, Armenia, the Greeks (a mild exaggeration), Media, and a bunch of places you've probably never heard of unless you study ancient history.

How Cyrus the Great became the messiah

For many people in the Western world, their first and maybe only exposure to the Achaemenid king Cyrus the Great is his role in the Bible, where he is praised as a savior of the Israelite people and is the only non-Jew to be referred to in the Bible as a messiah, that is, "God's anointed one." As the Jewish Virtual Library explains, the reason for this is that prior to Cyrus' intended conquest of the entire world, the Jewish people were being held captive by the Babylonians, who had besieged Jerusalem and destroyed the Temple of Solomon. Once Cyrus had conquered Babylonia, he restored the captive people of Judah to their homeland and told them to build a new temple. Cyrus' policy of religious tolerance meant that he encouraged the Jewish people to practice freely their worship of God.

However, it's important to understand that Cyrus' support and defense of the Jewish people was for religious reasons, namely his own religion, Zoroastrianism. Cyrus believed in a dualistic universe where the fate of the world was determined by the efforts of two main gods, one good and one evil. He also believed that an apocalyptic battle was forthcoming and that his god could use all the support he could get. Believing that the Jewish god Yahweh was a benevolent deity on the good side, Cyrus supported the Jews' worship for his own religious ends.

The Persians invented taxes

Prior to the Achaemenid Empire, the idea of citizens and provinces paying tribute to a king in the form of gifts of money and other wealth was an established practice. But even during the reigns of Cyrus II and his successor Cambyses, this process was not strictly regulated. As the Encyclopedia Iranica explains, it was up to Darius I, known as Darius the Great, to institute a systematic and regulated system that would prove to be sustainable in such a large empire, one which continues to influence the modern conception of taxation. The Behistun Inscription explains how Darius began his new system in 519 BCE, and the empire was divided up into tax districts. Each of these districts was then measured in area and classified according to crop type and harvest yield, essentially establishing the size and wealth of each district. Each district subsequently had to pay a silver tax proportionate to average crop yield over a period of several years.

For example, Babylonia and Egypt were known for their wealth and therefore contributed a larger share of taxes than other provinces. In fact, these two were so well-known for their production of crops that in addition to the silver tax, they were required to supply a large amount of grain as a food source for soldiers stationed in those regions. India, famous for its quantity of gold, paid their Achaemenid rulers in gold dust.

The Persians' annual wizard genocide holiday

When you hear the word "Magi" these days, you almost definitely picture the Three Kings who brought gold, frankincense, and myrrh to the baby Jesus. However, the word "Magi" actually referred to an immigrant group within the Persian Empire who became so associated with the priestly caste of Zoroastrianism that the word magus came to mean "wizard" and is the root of the English word "magic." As Ancient Origins explains, the Magi were originally a Median tribe that had been conquered by Cyrus and suddenly found themselves forcibly Persian. Once they found their role as religious leaders, soon there were Magi in every king's court. When the king Cambyses assassinated his own brother and heir Smerdis, the Magi tried to cover up Smerdis' death by putting a look-alike on the throne. The story ends with Darius killing the imposter and the Magi who put him on the throne and taking up the kingship for himself. (It is important to remember that this is Darius' version of events.)

Even though it's pretty likely that Darius killed Smerdis himself and then made the Magi his convenient political scapegoats, the Persians believed Darius' story. After Darius slaughtered every Magian priest and eunuch in the palace and paraded their heads out to the people, the Persians followed suit by killing every Magus they could find. What's worse, the Slaughter of the Magi became an annual holiday, marked by feasting and hate crimes.

Cambyses turned a man into a chair

The majority of information we have about the Achaemenid Empire comes from non-Persian authors, primarily Greek historians like Herodotus, Plutarch, and Strabo. The Greeks were, of course, enemies of the Persians, so their version of events should often be taken with a grain of salt. For example, the legendary ruthlessness and cruelty of the Persians described by these authors is probably, uh, exaggerated. However, Herodotus also says, while speaking of Persian culture, that the worst sin a person could commit in the eyes of a Persian is to lie. After that, they say, the worst thing you can do is be in debt, because someone in debt is by necessity bound to tell lies. One story that highlights both the alleged cruelty and disdain for dishonesty comes later in Herodotus' history.

During the rule of Cambyses II, the second Achaemenid king, a corrupt royal judge named Sisamnes was found guilty of taking a bribe and subsequently issuing a dishonest judgment. As punishment, Cambyses had Sisamnes flayed alive and then ordered all of his skin to be turned into leather with which he had the chair on which Sisamnes had proclaimed his judgments upholstered. Cambyses then appointed Sisamnes' son Otanes as the new judge in his father's place — but made him sit on the chair made from his father's skin as a reminder of the dangers and responsibilities that came with his royal position.

Possibly the most horrible torture of all time

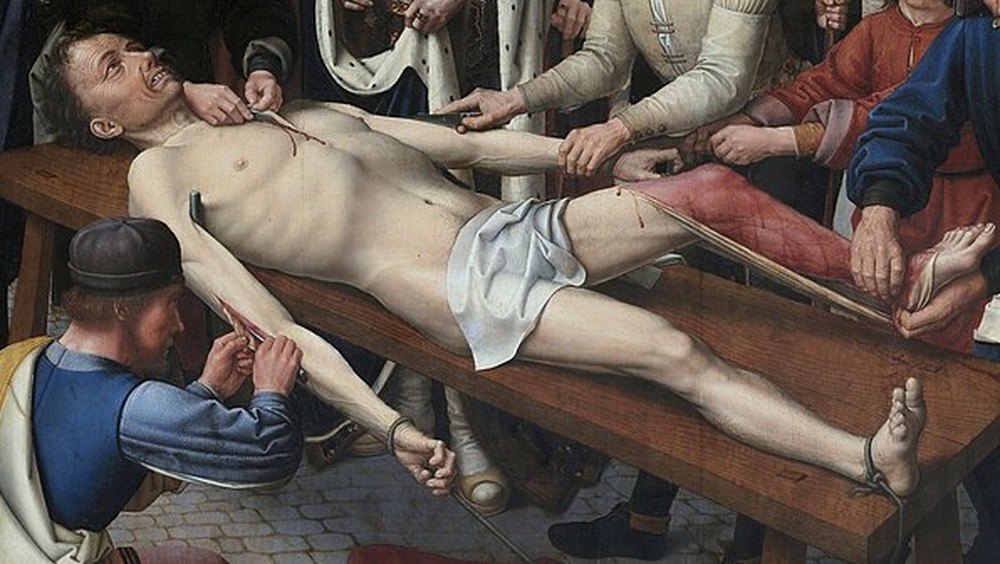

A story from the Greek biographer Plutarch's Life of Artaxerxes highlights an example of the grandiosely exaggerated cruelty of the Persians. According to Plutarch, following the death of Darius II, his eldest son Artaxerxes was placed on the throne, but his brother Cyrus the Younger attempted a coup. When the two brothers battled, a regular soldier named Mithridates accidentally killed Cyrus by spearing him through the eye, not knowing he was the prince. Artaxerxes wanted credit for killing the young pretender to the throne, so although he lavished Mithridates with gifts and honors, the official reason was that Mithridates had carried the king's horse gear for him. However, one night Mithridates got drunk and explained what really happened, and once word of Mithridates' betrayal of the king's trust reached Artaxerxes, Mithridates was sentenced to an execution so brutal that it's almost certainly fictional.

Mithridates was sentenced to die by scaphism, which Plutarch calls "the torture of the boats." The victim is laid between two boats and sealed up like a boat cocoon, with his head, hands, and feet left sticking out. His face is then covered with milk and honey and left exposed to the elements. The victim is left to rot in the sun as flies and maggots consume his face and bugs devour his body as the boats fill up with the man's excrement. Mithridates, Plutarch says, lasted 17 days.

An execution device of almost ridiculous proportions

The lives and reigns of the Achaemenid kings Xerxes II and Sogdianus are only attested to in the History of the Persians by Ctesias, a notoriously unreliable source. According to Livius.org, Sogdianus was the half-brother of Xerxes II, the legitimate heir of Artaxerxes. Sogdianus conspired against his brother and had him murdered while he was drunk, only 45 days into his reign. At this point, Sogdianus ascended to the throne, but he wouldn't enjoy a long or fruitful reign, either. Another half-brother, named Ochus, was higher in rank than Sogdianus and consequently felt slighted that he had not become king. Ochus conspired to overthrow Sogdianus and named himself King Darius II Nothus ("the Bastard") six months into Sogdianus' reign. Ctesias says that Sogdianus was "thrown into the ashes" but doesn't provide more information on his execution than that.

Fortunately, a deuterocanonical book of the Bible does give us more info on death by ashes. According to 2 Maccabees, the Persians had a tower 75 feet high that was filled with ashes, with a steep, narrow opening at the top. The prisoners would be pushed into the ashes from this opening, and the executioners would turn wheels from the outside that would constantly stir up the ash. In the end, the prisoners, even short-lived kings, would die of suffocation by the ever-swirling ashes.

The trouble with Greece

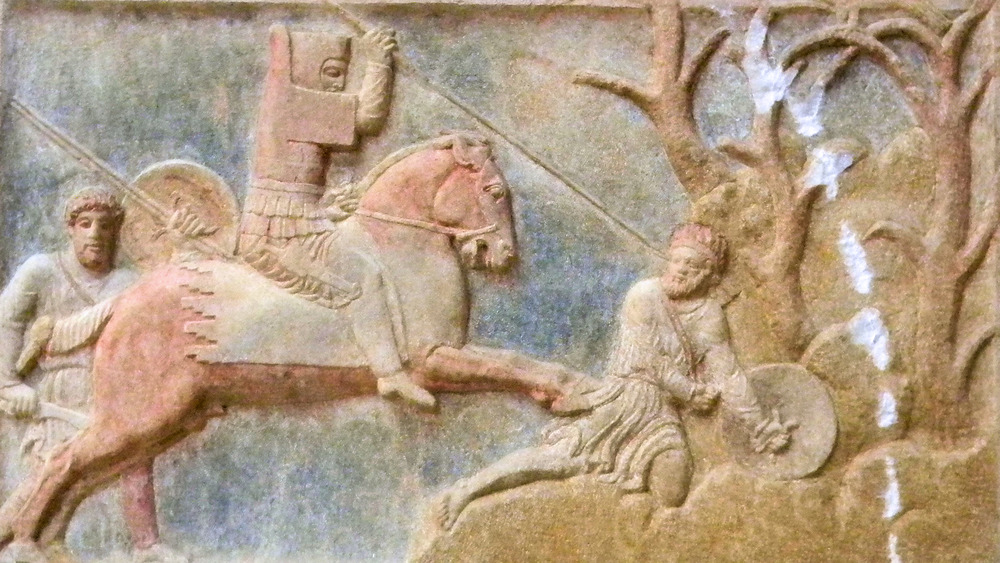

During the reign of Darius the Great, when the Achaemenid Empire reached its greatest extent, the Persians began expanding into mainland Europe. As the Ancient History Encyclopedia explains, this led to Greek regions such as Ionia, Thrace, and Macedonia falling under Persian control by the early fifth century BCE. With those conquests under his belt, Darius next planned to subjugate the rest of Greece. In 491 BCE, Darius sent ambassadors asking the Greeks to submit to Persian authority. The Greeks executed the ambassadors, and the normally at-odds city-states of Athens and Sparta formed an alliance for the protection of all of Greece. In response to this outrage, Darius sent 600 ships and 25,000 soldiers to invade the Greek islands known as the Cyclades. This invasion and a subsequent one by Darius' successor Xerxes led to campaigns known as the Persian Wars, conflicts which contained some of the most famous battles in history.

The Battle of Marathon was a decisive victory for the greatly outnumbered Greeks, and the legend of the messenger reporting the Greek victory is the source of the modern marathon race. The Battle of Thermopylae, dramatized in 300, saw a small band of Spartans against a much larger Persian force, and the Battle of Salamis was a resounding naval victory for Athens that established them as a world power.

The elite regiment of undying Persian soldiers

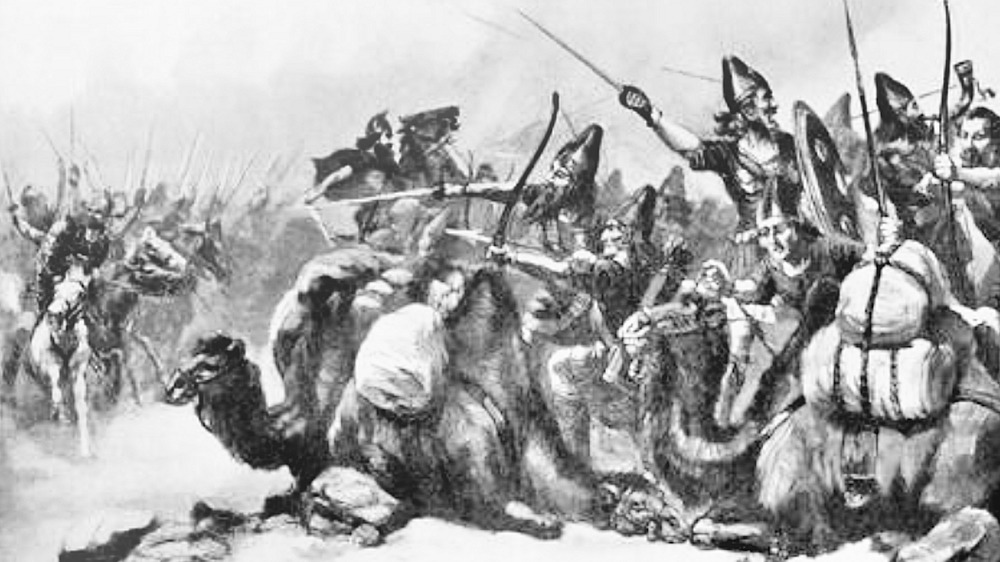

The Greek historian Herodotus says during his description of the Battle of Thermopylae that the Persian army employed an elite force known as the Athanatoi, or "the Immortals." Livius.org records Herodotus' explanation for that title, namely that it was a corps of 10,000 elite soldiers, and that number never changed. Whenever a soldier from this unit died or became ill, he was immediately replaced so that there were never any more or any less than exactly 10,000 soldiers in the unit. The Immortals were all hand-picked native-born Persians under the command of one of Darius' satraps. These men had the finest armor of the entire army, which "glittered with the gold which he carried about his person in unlimited quantity." They additionally enjoyed a baggage train carrying any women or servants they required, and they had a diet of special food carried especially for them by camels and mules.

Herodotus goes on to describe the equipment of the Immortals, saying that their uniforms included a soft felt cap, a shirt of scale mail, and pants (considered barbaric by the tunic-wearing Greeks). Their weapons included wicker shields, bows with cane arrows, short spears, and short swords hanging on their right sides. The Immortals were, according to Herodotus, the ones who managed to attack the Spartans from the rear after they had blocked off the coastal path through Thermopylae.

The Persian Empire begins with a Great and ends with a Great

The Persians' failed invasions of Greece in the fifth century marked an end to the period in which the mighty Achaemenids seemed truly invincible. As Livius.org notes, these defeats and Greek provinces in mainland Europe and Asia Minor declaring independence from the empire marked a shift within the Persian Empire from an expansionist one to a more static power. Nevertheless, Xerxes managed to hold the empire together and keep it relatively stable during this transitional period, and the Achaemenids continued to be the most powerful state in the world for several generations. However, by the fourth century BCE, civil war broke out among the Achaemenid dynasty, and the Persians had trouble holding on to Greek conquests and lost Egypt altogether for a while.

The real fall of the Achaemenid Empire, however, came at the hands of a guy you might have heard of. The death of Artaxerxes III led to a succession crisis in Persia when Artaxerxes IV was displaced by the self-styled Darius III, a distant relative. Various satrapies revolted as a result of this crisis, and Darius' attention was focused on putting down these rebellions. This gave an opening to a young Macedonian upstart named Alexander the Great, who defeated Darius and named himself the last of the Achaemenid kings. After Alexander's death, the Persian Empire was divided, and parts of it became the newly formed Seleucid Empire.