Anna May Wong: The First Asian-American Movie Star Hollywood Forgot

Throughout her life, Anna May Wong refused to settle for less. She ignored her father when he dissuaded her from acting and she rebelled against Hollywood when they continued to typecast her in stereotypical parts. Although racism plagued Wong throughout her life and she was repeatedly denied the leads she deserved, Wong remained committed to fighting against "the typecasting and racism of Hollywood." She was also a big part of the Chinese war relief effort during World War II.

The first Chinese-American actress, Anna May Wong was a woman of many talents, at one point even creating a cabaret act, which included songs in a variety of languages. But despite her talents, white women were repeatedly chosen over Wong to portray Chinese women on-screen. By the end of her life, Wong had become incredibly disillusioned with the American film industry, but she ended up creating up till the end of her life. One year before she died, she was given a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, but during her life she never won any awards. In fact, one of the most famous stories about Wong involves the fact that a German woman received an Oscar for portraying a Chinese woman in a film that actively passed over Wong.

Despite the fact that Asian-Americans in Hollywood still suffer from discrimination and stereotypical casting, over the past century Hollywood has changed largely thanks to Wong's persistence. This is the story of Anna May Wong: the first Asian-American movie star Hollywood forgot.

Anna May Wong's early life

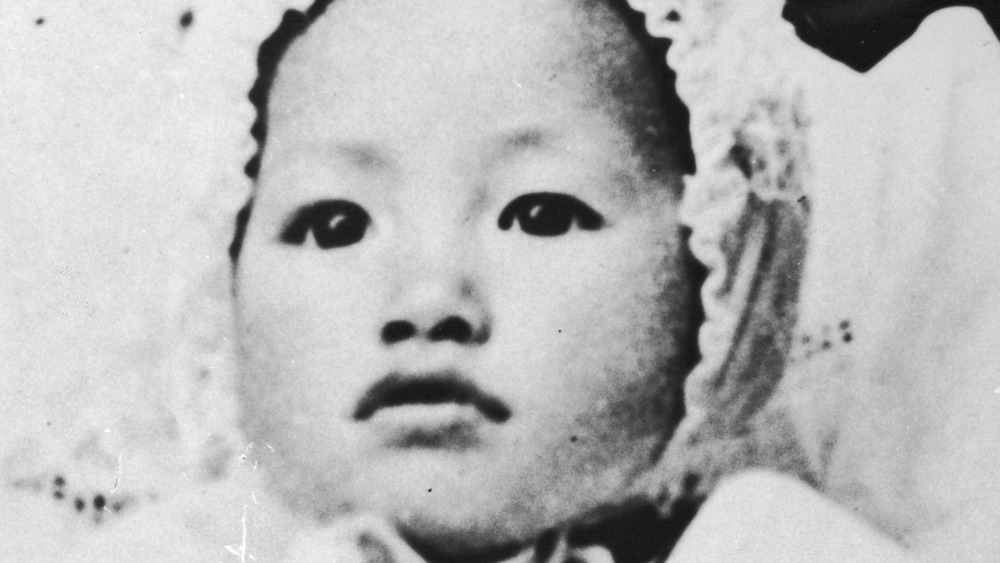

Anna May Wong was born Wong Liu Tsong, also spelled Huang Liu Tsong, on 351 Flower Street close to Los Angeles's Chinatown on January 3rd, 1905. Both of Wong's sets of grandparents had immigrated to the United States from China by the end of the 1850s, including her grandfather who immigrated from Taishan, China, almost 30 years before the implementation of the Chinese Exclusion Act.

According to Anna May Wong: From Laundryman's Daughter to Hollywood Legend, Wong's parents established a laundromat called Wong Laundry in Chinatown. Before Wong's birth, her family moved to Figueroa Street and opened Sam Kee Laundry, where a young Wong later worked "behind the counter in the laundry during the Saturday rush of customers."

Anna May Wong was the second oldest out of eight children, and initially she and her older sister attended a mostly-white school. However, as reported by Time Magazine, they eventually transferred to the Chinese Mission School in Chinatown because of the constant racial abuse, verbal and physical, from the other students. According to Wong herself, before they transferred "we lived in such terror that we couldn't keep our minds on our lessons. We become ill with fright. All of our bright dreams of making friends with our schoolmates, of standing well in our lessons, of willing the approbation of the teachers vanished. We were just two hunted, tormented little creatures."

Anna May Wong falls in love with movies

Anna May Wong became enamored with the silver screen almost instantly. Instead of going to school, sometimes she'd go to the nickelodeon, the original indoor movie theatre, and watch silent films while mesmerized. And according to the National Women's History Museum, since film production had moved to California in the 1910s after being based in New York, Wong was also able to watch movies as they were being made.

Although Wong's father refused to accept her dreams of becoming an actor, Wong knew from the age of nine that she was going to be a great one. And according to Time Magazine, James Wang, one of the earliest Chinese actors, advised her, "There is no reason you should not make good if you are willing to work hard. You will do." Wang had noticed Wong while shooting a film in Chinatown, and even though he was friends with Wong's father, without telling him Wang helped Wong get her first role in The Red Lantern in 1919. In a single scene, Wong appeared as an extra carrying a lantern. Even though the role was small and uncredited, it was just the steppingstone Anna May Wong needed.

A full-time actress

Wong continued to attend school and work as an extra in movies, but in 1921 she dropped out of Los Angeles High School to work as an actress full-time. For a time, she had to work as a model as well in order to earn a living, but in 1922, at the age of 17, Wong was cast as Lotus Flower, the leading role for The Toll of the Sea, one of the first films in color.

According to the National Women's History Museum, although Wong frequently auditioned for leading roles, she was always relegated to stereotypical roles or supporting characters. One such example is The Thief of Bagdad, where she played a "Mongol slave woman" who's a handmaiden for the Caliph's daughter. This film is considered her "breakout role" and although Wong didn't have a big part, she's described as having a "luminous presence" in the movie.

But almost all of Wong's roles, including the one in The Thief of Bagdad, objectified and exotified her. And according to Harper's Bazaar, when a movie did feature an Asian character as its lead, white actresses were given the parts to play while wearing "yellowface." Apparently, during the filming of The Crimson City, which came out in 1928, Wong had to teach a white actress named Myrna Loy how to use chopsticks correctly in order to play Onoto, the Chinese lead, while Wong was given a minor supporting role.

Anna May Wong Productions

In an attempt to counteract the stereotypical representation of Asian cultures in Hollywood, in 1924 Anna May Wong and George M. Martin, her manager, started Anna May Wong Productions because Wong wanted to make films that actually starred Asian-Americans in Asian leads. However, in Perpetually Cool: The Many Lives of Anna May Wong, author Anthony B. Chen suggests that Wong was merely "looking to cash in on her ethnic heritage" and that the whole project was nothing more than a business venture.

The company intended to make a series of films about "ancient Chinese legends," but this fact was soon exploited by her business partner Forrest B. Creighton, who had signed on to raise money for Anna May Productions. In addition to changing his contract without Wong's consent, Creighton used Wong's name to misrepresent the project to investors. Wong was able to get a temporary injunction against Creighton and although he backed off, according to Time Magazine, Wong ended up dissolving the production company after the lawsuits.

Chinese actors in the United States

In the United States during the early 20th century, Chinese actors were rarely given the opportunity to play Chinese leads. According to Anna May Wong herself, "rather than real Chinese, producers prefer Hungarians, Mexicans, American Indians for Chinese roles." Part of this was also due to the anti-miscegenation laws that several states had adopted, which criminalized mixed-race marriage and as a result reinforced racist conventions that prevented Wong from sharing an onscreen kiss with a white man. Hollywood's desire to prevent any suggestion of mixed-race love is noted even in the production notes for Across to Singapore.

Even when Wong filmed love scenes, according to Anna May Wong, "extraordinarily passionate scenes between the two wound up on the cutting-room floor for screenings in the United States." The difference is noted even when comparing the advertisements for films in South America and the United States.

According to Written Chinese, Wong herself ended up being generalized as a "minority" and in addition to playing a Mongolian woman in The Thief of Bagdad, she was cast as a Hispanic woman in Thundering Dawn (1923) and the Native American Tiger Lily in Peter Pan (1924).

Anna May Wong moves to Europe

Frustrated with Hollywood's racism and discrimination, Anna May Wong moved to Europe. According to the Los Angeles Times, Wong was a hit in Europe, and she travelled around the continent starring in German, French, and English films. In 1933, Wong revealed exactly why she had decided to leave the United States, stating, "I was so tired of the parts I had to play. Why is it that the screen Chinese is nearly always the villain of the piece, and so cruel a villain–murderous, treacherous, a snake in the grass. We are not like that."

According to Anna May Wong, Piccadilly (1929) was one of Wong's most famous films and is "considered among the best of films from the silent era in England." And according to the National Women's History Museum, Wong also did a number of stage productions including an operetta in fluent German. It was while she was in Germany that Wong became friends with Marlene Dietrich. Several years later, the two of them would work together on Shanghai Express (1932).

In March 1929, Wong appeared in the English play The Circle of Chalk, and many theater critics, rejecting the fact that the figure they'd spent years objectifying had finally been given a voice, spent hundreds of words criticizing her voice. When Wong finally addressed the press, she said the debate over her accent was boring and then spoke in Chinese "so that no one would understand her."

Returning back to America

Seeing how big of a hit Anna May Wong was in Europe, Hollywood decided that they had to convince her to come back. According to the National Women's History Museum, Paramount Studios reached out to Wong in the 1930s and claimed that if she came back to the United States film industry then they'd give her leading parts.

As reported in Esquire, "the promise would prove a disappointment, as she was still asked to play stereotypical Asian roles in B-movies." This was apparent from one of her first movies back, 1931's Daughter of the Dragon, where Wong played the daughter of Fu Manchu and "carries on the notorious way of life" after he dies. And according to Written Chinese, although Paramount had promised Wong a three-picture deal, they didn't give her any pay raise.

One of the few exceptions was Daughter of Shanghai, which came out in 1937 and featured Asian-American actors as the leads, even though Anna May Wong was the only one out of the two who was actually Chinese. Irritated, Wong travelled back to Europe once more and after three years in England, she set her sights on the role of O-lan in The Good Earth.

Anna May Wong and The Good Earth

In 1935, Metro Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) chose Luise Rainer, a German actress, over Anna May Wong for the role of O-lan, the Chinese lead in The Good Earth. According to Esquire, MGM asked Wong to audition instead for the role of a concubine. In response, she said "I'll be glad to take the test, but I won't play the part. If you let me play O-lan, I'll be very glad. But you're asking me—with Chinese blood—to do the only unsympathetic role in the picture, featuring an all-American cast portraying Chinese characters."

But MGM ultimately refused to consider Wong for the role of O-lan, partly because a white man had already been cast as O-lan's husband and MGM refused to allow a mixed-race onscreen kiss. According to Vanity Fair, MGM even incorporated "yellowface" into Rainer's appearance in order for her to "look Chinese." Rainer was later awarded the Academy Award for Best Actress for her role in the movie.

Wong was devastated at MGM's decision and decided to embark on a trip to China partly to visit her father in addition to reconnecting with her Chinese heritage. According to Anna May Wong, "while the Hollywood magazines were ablaze with stories about the filming of Buck's novel, Anna May celebrated her thirty-first birthday with preparations for her trip to China."

Visiting China for the first time

Initially, Anna May Wong wasn't well received in China and the press criticized her for acting into Western orientalization. According to Vanity Fair, MGM had an adviser for the Chinese government and he claimed that "whenever she appears in a movie, the newspaper print her picture with the caption 'Anna May again loses face for China.'"

And according to Written Chinese, although Wong was "treated like royalty" when she arrived, the Chinese press was highly critical of her role in misrepresenting Chinese culture. But before long, Wong "soon charmed the Chinese people and was a massive hit." At the end of the day, Wong knew how to market herself.

However, according to Esquire, Anna May Wong later said, "It's a pretty sad situation to be rejected by the Chinese because I'm too American, and by American producers, because they prefer other races to act Chinese parts." Wong traveled around China for the whole of 1936. It was upon returning to the United States that Wong made Daughter of Shanghai, which prompted Paramount to sign her for another three movies.

Working for war relief

During World War II, Anna May Wong stopped acting and dedicated her time to the war relief effort for China. According to Written Chinese, Wong was able to get her family out of China in 1938 and "worked with Chinatown communities to get rid of the Chinese Exclusion Act," which unfortunately remained in effect for another five years.

In addition to talking to Chinese communities about war relief efforts, Wong also addressed troops over the radio. And according to A Feeling of Belonging: Asian American Women's Public Culture, 1930-1960, at one point she was also signing autographs in exchange for donations in order to raise money for Chinese War Bonds. In addition to working for United China Relief Fund, according to Herdacity, Wong also toured with the United Service Organizations, Inc., which offered entertainment performances for active-duty military members.

And according to From Beneath the Hollywood Sign, Anna May Wong didn't completely abandon her career. In 1942, she made two pro-USA propaganda films, Lady From Chungking and Bombs Over Burma, in addition to some low budget movies for Paramount during the course of the war. And the salary she earned from both propaganda films was donated to the war relief effort.

Anna May Wong's mixed legacy

For many, Anna May Wong has a mixed legacy. At times, she advocated for accurate Asian representations, like during the production of Dangerous to Know, when Wong "outright refused" to use Japanese mannerisms for a Chinese character, according to Esquire. But simultaneously, Wong accepted roles that required her to act as a race other than her own and often accepted stereotypical roles herself, including one in Daughter of the Dragon because, according to the National Women's History Museum, "she was promised that she would be able to appear in a Josef von Sternberg film."

And according to Written Chinese, when Wong was criticized in China for the stereotypical orientalist roles she played, she claimed that this was because no other roles were being offered to her. However, Wong later admitted that "because of her more western upbringing, she knew very little about authentic Chinese culture, and assumed the stereotypes of philosophical, tea drinkers were correct." But despite this, Wong can be credited for "open[ing] a door for future Asian-American actresses."

In 1951, Anna May Wong starred in a detective television series titled The Gallery of Madame Liu-Tsong, and, according to From Beneath the Hollywood Sign, became the first Asian-American to be the lead in their own TV show. Not only was the show "written specifically for her," but the title character was named after her Chinese birth name. Unfortunately, according to Vulture, the series was cancelled after just one season and "no scripts or episodes seem to have survived."

Anna May Wong's untimely death

Despite the cancellation of The Gallery of Madame Liu-Tsong, Anna May Wong continued her film and television career. From Beneath the Hollywood Sign reports that Wong did a number of guest spots on various television shows, and she also was the first Chinese-American to host a U.S. docuseries on China in 1956. The docuseries even included some footage from Wong's own trip to China 20 years earlier.

Unfortunately, by the end of her life Wong was drinking significantly more, struggling financially, and suffering from failing health. Wong's final role was Portrait in Black, which came out in 1960, and sources differ as to whether or not she dropped out of production for Rodgers and Hammerstein's Flower Drum Song (1961) or if she lost her life before production began.

Tragically, Anna May Wong died of a heart attack on February 3rd, 1961 at the age of 56. According to Bizarre Los Angeles, two years earlier Wong had said "When I die, my epitaph should be: I died a thousand deaths. That was the story of my film career. Most of the time I played in mystery and intrigue stories. They didn't know what to do with me at the end, so they killed me off."