The Untold Story Of The Newsboys' Strike Of 1899

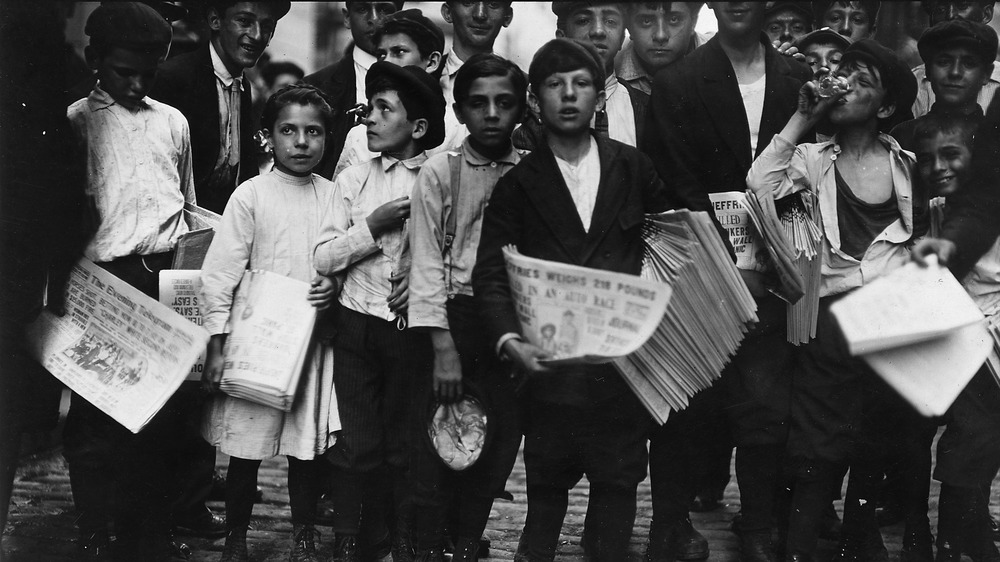

Although everyone assumes that the newsies were all young houseless orphaned children who sold newspapers all day, the newsboys actually ranged in age, housing security (per the Village Preservation Blog), parental security (according to David Nasaw's book Children of the City), and often went to school (according to William A. Corsaro, writing in The Sociology of Childhood) in between selling the morning and afternoon editions. The newsies were instrumental in the spread of information, and in the summer of 1899, they showed the city of New York just how necessary they were.

During the two week strike, the newsies were able to cut the circulation of the New York Evening World and the New York Evening Journal in half, writes the New York Daily News. And although the strike's demands weren't exactly met in the end, the fact that a compromise was even offered to the newsies showed the potential of collective organizing.

In 1992, Disney made a musical film about the strike, Newsies, starring a young Christian Bale (via a clip on YouTube) (who didn't know that it was a musical when he signed on, as Movieline recounts). This is the untold story of the Newsboys' strike of 1899.

What caused the Newsboys' strike?

During the Spanish-American War, which started in April, 1898, the price that newsies bought their newspapers for was increased by publishers from 5 cents per newspaper to 6 cents per (from 50 cents per bundle of 10 to 60 cents), according to Village Preservation. Since the war grabbed the public's attention, the newsies didn't remark on the price increase since it wasn't so difficult to sell the newspapers (via the You're Wrong About podcast).

But after the war ended in December, 1898, not all the publishers brought their prices back down. William Randolph Hearst, owner of the New York Evening Journal, and Joseph Pulitzer, owner of the New York Evening World, left the prices of their newspaper bundles at the higher rate of 60 cents per.

American Heritage writes that the reason Hearst and Pulitzer refused to reduce their prices was due to their own personal war. In an attempt to outsell the other, they'd poured a great deal of money into making their papers fancy and enticing. Unfortunately, they were still losing money, so they raised the prices for the newsies "in hopes of reducing their losses to more manageable levels."

Meanwhile, with the war over, the price increase started to feel more and more noticeable to the newsies by the summer of 1899. "And by now it was apparent," writes American Heritage, "that the temporary increase would become a permanent one unless they did something about it."

The main players of the Newsboys' strike

Although the strike didn't have a centralized origin, most agree that one of the first incidents occurred in Long Island City. Per American Heritage, on July 18, a group of newsies tipped over the wagon of a Journal deliveryman in Long Island City and demanded the prices be lowered. News of the newsies' action traveled across Manhattan and Brooklyn, and by the next day, July 19, newsies from the various boroughs gathered in City Hall Park, organized a union, and announced a strike the following day unless Hearst and Pulitzer brought the prices down. News of the strike (now posted at City Hall Park 1899) had been spread fast across the boroughs, through leaflets and word-of-mouth, and according to Village Preservation, at some of the later newsies' rallies there were upwards of 5,000 newsies.

The initial leaders of the Newsboys' strike, writes Faces of the Past, were 18-year-old Louis "Kid Blink" Baletti and 21-year-old David Simons. At one point, Kid Blink was even awarded a floral horseshoe during one of their rallies for giving the best speech, having roused the crowd with the words, "Ten cents in the dollar is as much to us as it is to Mr. Hearst the millionaire. Am I right?"

Two weeks of strikes and scabs

Although there was a handful of girls and women who participated in the Newsboys' strike, according to Crying the News by Vincent DiGirolamo, they "played only peripheral roles." The Kings and Queens of Brooklyn says that Racetrack Higgins and Morris Cohen were also part of the initial organization, and after Kid Blink and Simons sold out they maintained the strike.

The newsies spent two weeks disrupting the distribution of Hearst's and Pulitzers papers. They sometimes even attacked scabs who sold the papers, although as Crying the News relates, Kid Blink emphasized that "A feller can't soak a lady." Village Preservation reports that the newsies marched through the streets of Manhattan and Brooklyn, halting traffic, and at one point crossing the Brooklyn Bridge with their rally. And according to the New York Daily News, it was an opportune moment for a strike since the Brooklyn streetcar operators were also on strike at the time and "de cops is all busy!"

Although neither Hearst nor Pulitzer took the strike seriously at first, soon they realized the effect that the newsies could have. The World's press run, for example, fell from 360,000 to 125,000.

Just one week into the strike, rumors started floating around that Kid Blink and Simons had been bribed and bought off by the newspaper publishers. Although they denied the charges, it was noted that the boys were wearing much nicer clothes than they usually would've worn.

Legacy of the Newsboys' strike

In response to Kid Blink's and Simons's betrayal, the newsies revoked the leadership positions of the two, says City Hall Park 1899, and chased them through the neighborhood. Kid Blink was able to avoid being beaten up by being arrested, and on July 28, 1899, the Evening Telegram reported how in the morning his mother bailed him out and "a band of newsboys stood outside and hooted at him as he passed."

In the end, the strike was only partly successful. On August 1, the newsies were offered a compromise. The price increase would remain, but the newsies could sell their unsold papers back to the World and the Journal for a full refund, says the New York Daily News. The next day, the newsies were back to work.

Unfortunately, the newsies union didn't survive. "The publishers ignored the union" in their final negotiations and as word traveled that the strike was over, the union seemed to dissolve.

The spirit of the newsies didn't die down so quickly, however. AFT Connecticut notes that there were several other similar strikes that happened over the next decade, such as the Hartford newsboys' strike of 1909 (detailed at the Connecticut History website). And as stated in Village Preservation, child labor laws wouldn't be considered for another 20 years. The fact that these children and young adults were coming together to demand that they even had rights was a monumental moment in history.