The Crazy Real-Life Story Of The Woman Who Created Vampira

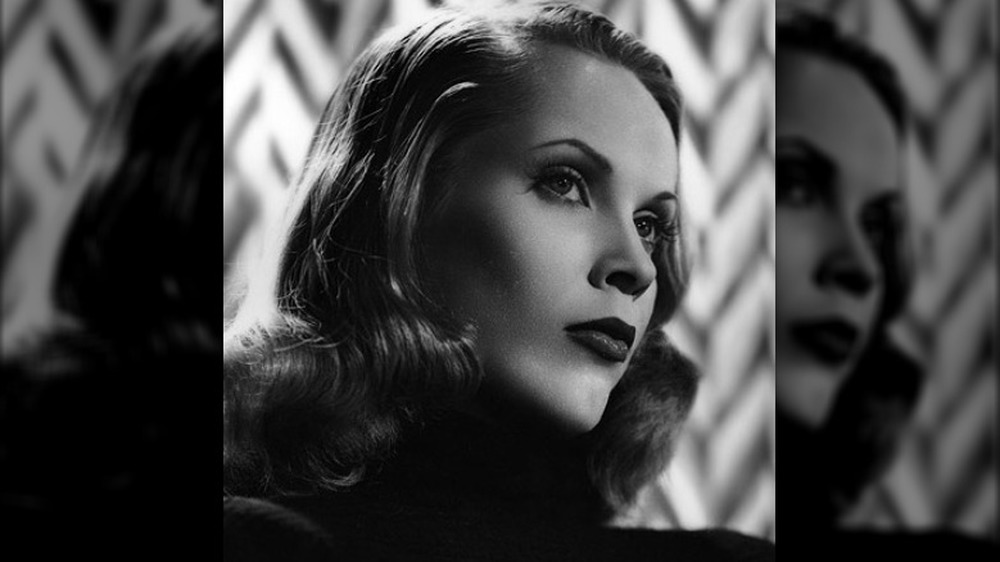

In May 1954, insomniacs, TV junkies, and horror movie fans in Southern California would see something unlike anything else on the tube. At the stroke of midnight, viewers tuning into Los Angeles' KABC-TV were greeted with the image of a ghostly figure slinking through a fog-shrouded hallway. Stepping into a tight closeup, a beautiful but vaguely sinister woman with impossibly arched eyebrows, coal-black hair, and deathly pale skin looked directly into the camera and emitted a blood-curdling scream, ushering in a new chapter in horror entertainment. This was Vampira, and television would never be the same.

Presenting classic (and not-so classic) horror and mystery films from her skull-bedecked sofa, Vampira mixed humor and scares in a sexy, hip, irreverent, and high camp formula that mesmerized an unsuspecting 50s audience and etched the blueprint that movie hosts from Zacherle to Svengoolie follow to the present day.

Although The Vampira Show lasted for just one year and wasn't seen outside of Southern California, it made its spooky, wasp-waisted hostess a national star. Vampira hobbed-knobbed with celebrities and made guest appearances on popular network shows. However, Maila Nurmi, the quick-witted woman in the skin-tight black dress, remained a mystery. As Vampira's creator, Nurmi was consumed by the role, rarely appearing in public out of character. In the years after Vampira's initial fame, Nurmi came to regard her alter ego as a blessing and a curse. This is the crazy real-life story of the woman who created Vampira.

Maila Nurmi's Finnish roots

For most of her professional life, Maila Nurmi claimed she was born in Petsamo, Finland. Most profiles of the actress repeat this as fact. However, the truth is a bit murkier. As detailed in W. Scott Poole's 2014 biography, Vampira: Dark Goddess of Horror, Nurmi was born Elizabeth Maila Syrjäniemi in Gloucester, Mass. In a bit of myth-making, she chose Petsamo as her birthplace to bolster her claim that she was the niece of Finnish Olympic diver Paavo Nurmi.

Nevertheless, Nurmi was of Finnish descent. Her father, Onni Syrjäniemi, arrived at Ellis Island in 1910 and settled in Gloucester sometime in the 1920s. There, he met Sophia Peterson. The couple married and Nurmi was born on Dec. 11, 1922. Her father worked as the editor of a Finnish newspaper, and later, as a lecturer in the temperance movement. Her mother was a part time translator and bookkeeper. During the Great Depression, the family moved to the Finnish enclave of Astoria, Oregon.

Nurmi rarely spoke of her youth. However, in a personal recording featured in the documentary, Vampire and Me, Nurmi revealed that her free-spirited ways often put her in conflict with her level-headed mother. "My mother was one of those people who could see an airplane already gracefully in flight and still insist it was too heavy to fly, and still BELIEVE that it was too heavy to fly," Nurmi said. " [She was] forever planning for a rainy day and warning you to wear clean underwear in case you're hit by a street car."

Maila Nurmi's long road to Hollywood

As a teen, Maila Nurmi often felt alienated from her practical parents — especially her mother who viewed Nurmi's imagination and whimsical nature as obstacles to her success. Frustrated with her daughter's fantasy life, Nurmi's mother once harshly reminded her, "You are just Elizabeth Syrjäniemi and you work at the fish cannery."

According to author W. Scott Poole, Nurmi was a self-described outsider, a dreamer with an intense fascination with comic strips, especially Terry and the Pirates. Her favorite character was the villainous pirate queen, the Dragon Lady, who, to Nurmi, represented an unrestrained freedom she was denied at home. In 1940, just after graduation, she left Astoria to create a life on her own terms.

Virtually penniless, she struck out for Los Angeles, the center of the film world. Aside from some modeling work, Nurmi was unable to make headway in Hollywood. She journeyed to New York where, in her own words, she "wormed her way" into Mae West's Broadway show Catherine Was Great. While pursuing a career on the stage, Nurmi also appeared in a horror-themed stage revue titled Spook Scandals.

As Nurmi explains in R.H. Greene's documentary, Vampira and Me, her work on Broadway drew the attention of legendary director Howard Hawks. "I was to be the new Lauren Bacall," Nurmi said. "He brought me [to Hollywood] saying I was a million dollar property. . ." Back in Hollywood, she found herself ignored by the studio and by Hawks. Frustrated, she tore her contract to pieces.

The birth of Vampira

Following her failed bid at movie stardom, Maila Nurmi spent a decade on Hollywood's fringes. Supporting herself as a pinup model, Nurmi molded herself into a sexy "girl next door" type for West Coast cheesecake magazines. By 1953, she was married to screenwriter Dean Riesner and working in a cloakroom on the Sunset Strip.

According to a 1983 career retrospective Nurmi wrote for Fangoria, the creation of Vampira was part of a convoluted plan to raise funds for a career change. "I wanted to become an evangelist and needed $20,000 to sponsor myself. . .," Nurmi wrote. Inspired by Charles Addams' popular Homebodies cartoons in The New Yorker, Nurmi believed that she could make a splash at choreographer Lester Horton's annual costume ball, the Bal Caribe, dressed as the strip's gaunt unnamed matriarch — maybe enough of a splash to get a producer to help her launch a live-action TV version of the Addams cartoon.

Although Nurmi didn't attract the attention of any Addams' associates, she nevertheless was the hit of the Bal Caribe. In a tight and tattered, homemade black dress and a rented wig, Nurmi took first prize in the masquerade's costume competition. "My flat-chested, barefooted Victorian vampire-matron was an unqualified success," Nurmi wrote.

Unbeknownst to Nurmi, she had caught the eye of KABC -TV program director Hunt Stromberg, Jr. Convinced he had found a way to liven up his station's late-night movie roster, he launched a months-long search to find the mysterious woman in black.

Vampira: the first horror hostess

Hunt Stromberg was at last able to locate Maila Nurmi when fashion designer Rudi Gernrich, who had been a judge at the Bal Caribe, identified her. As Nurmi explains in Vampira and Me, Stromberg wanted her to perform as the Addams character. "'We can't do that,' I said. 'It belongs to Charles Addams. It's not my character,'" Nurmi said. ". . . So, I said, 'Give me a few days,' and I came back with a vampire. . . I kept the dress and the black hair, but I turned her into a vamp. I gave her platform shoes and fishnet stockings and I slit the dress. . ."

Nurmi also looked to the BDSM subculture for inspiration. "I took a lot of things from a magazine called Bizarre. I didn't know what a dominatrix was, but that's obviously was what [I] was emulating," Nurmi explained. Yet, the most extreme aspect of Nurmi's transformation involved the sculpting of her miniscule midsection. Slathering a homemade concoction of papaya powder (an ingredient used in meat tenderizers) and cold cream on her abdomen and binding it with a rubber innertube, Nurmi "melted" her waist to 17 inches. Dubbed "Vampira" by Nurmi's husband, the first TV horror hostess was born.

Lounging on a Victorian sofa in her candlelit "attic," Nurmi as Vampira introduced B-grade horror in her patented, sardonic style. Interspersing humorous sketches with occasional jabs at the night's movie, The Vampira Show established the format that later horror hosts would employ throughout the monster movie boom of the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Vampira becomes a late night hit

The Vampira Show hit the airwaves at midnight on Saturday, April 30, 1954. It was an immediate ratings hit for KABC-TV. From the beginning, it was obvious that viewers weren't tuning in for the movies. Combining camp, gallows humor, and sex appeal, Vampira offered late night audiences an alternative to the typical 1950s depiction of domestic womanhood. Self-assured and simmering with sex, Vampira was the antithesis of the sitcom housewife.

Despite being a local program, The Vampira Show gained national recognition. Just three weeks after its premiere, Newsweek covered The Vampira Show. Soon after the Newsweek write-up, Vampira was the subject of a three-page photo feature in LIFE Magazine, an honor unheard of for a local television show. As Maila Nurmi explained to filmmaker R.H. Greene, KABC didn't have to promote the show. "Everybody automatically wrote about it," Nurmi recalled. "[Vampira] advertised herself."

Rarely appearing in public out of character, Nurmi kept Vampira in the public eye by tooling around L.A. in a long, black 1932 Packard touring car to the delight of her legions of fans. "I became the girl of the minute," Nurmi said. ". . .I was the number one item around. . . "

Although TV viewers outside of Los Angeles were denied The Vampira Show, they did catch a glimpse of its star when Vampira appeared on such network shows as The Red Skelton Show. Fan mail poured in from around the globe. For just over a year, the world was in the grips of Vampira-mania.

Vampira and James Dean

According to The Death of James Dean, by Warren Newton Beath, Maila Nurmi first spotted James Dean at the premiere of the Audrey Hepburn film, Sabrina. Although Nurmi didn't meet Dean at that event, she did strike up a friendship with a fan named Jack Simmons. Simmons so admired Nurmi that there was little he wouldn't do for her. One day while the pair were hanging out at Googies, a popular Sunset Strip coffee shop, Nurmi spotted Dean. "That's the only guy in Hollywood that I want to meet," Nurmi exclaimed. Simmons rushed to introduce Dean to Nurmi, and the two became fast friends. "Instantly we were magnetized to one another," Nurmi recalled to filmmaker R.H. Greene.

Sharing a similar sense of humor and obsession with the macabre, Dean and Nurmi were very close for a short time. As Dean's star rose, the press was quick to link the friends romantically. Still, Nurmi and Dean were kindred spirits not lovers.

Sadly, a mistakenly perceived jealousy sparked by Dean's ascent to fame and Nurmi's waning popularity with the end of The Vampira Show drove a wedge between the friends. In an interview with gossip columnist Hedda Hopper, Dean callously stated, "I don't date cartoons," adding that Vampira was just "a subject about which I wanted to learn."

Dean and Nurmi reconciled, but the damage was irreversible. They would speak by phone for the last time the day before Dean's fatal 1955 car crash.

When Vampira met Ed Wood

Airing live in the pre-videotape 1950s, The Vampira Show was not seen outside the Los Angeles area, and, consequently, there is no surviving footage. However, horror fans finally glimpsed what they had only dreamed about for decades when a promotional film for KABC-TV featuring the show's opening segment was unearthed in the late 1990s. Despite this brief glimpse at Vampira exercising her sardonic wit over a "vampire cocktail," Maila Nurmi is best remembered for her appearance in Ed Wood's notorious Plan 9 From Outer Space.

Nurmi first met Wood in 1954 at the home of Famous Monsters of Filmland editor Forrest J. Ackerman during a birthday party for horror icon Bela Lugosi's son. In the 1995 documentary, The Haunted World of Edward D. Wood Jr., Nurmi recalled encountering the director. "I thought, 'This is a pathetic buffoon. This is a man who doesn't even know his own shortcomings' — kind of sad," Nurmi said.

One year later, Nurmi was entertaining serious film offers from the big studios, but, by 1956, The Vampira Show was over, and Nurmi's fortunes drastically changed. Living on $13 a week unemployment insurance, the $200 offer from Wood to appear in his next Z-grade feature seemed a godsend. The script, however, was anything but heavenly. "I was unable to say the words," Nurmi recalled. ". . . I was so offended by the dialogue." Not wanting to miss a payday, Nurmi convinced Wood to let her play the part as an entranced and mercifully mute ghoul.

After Vampira

Maila Nurmi's run as the world's most famous glamour ghoul was tragically short. Although Vampira had garnered the actress national fame, appearances on popular network variety shows, and an Emmy nomination for most outstanding female television personality, KABC-TV cancelled The Vampira Show after just one year. With Nurmi retaining 51% ownership of her creation, she refused ABC's offer to buy the rights to Vampira. The decision led to the affiliate terminating her contract and unceremoniously pulling the show from the air.

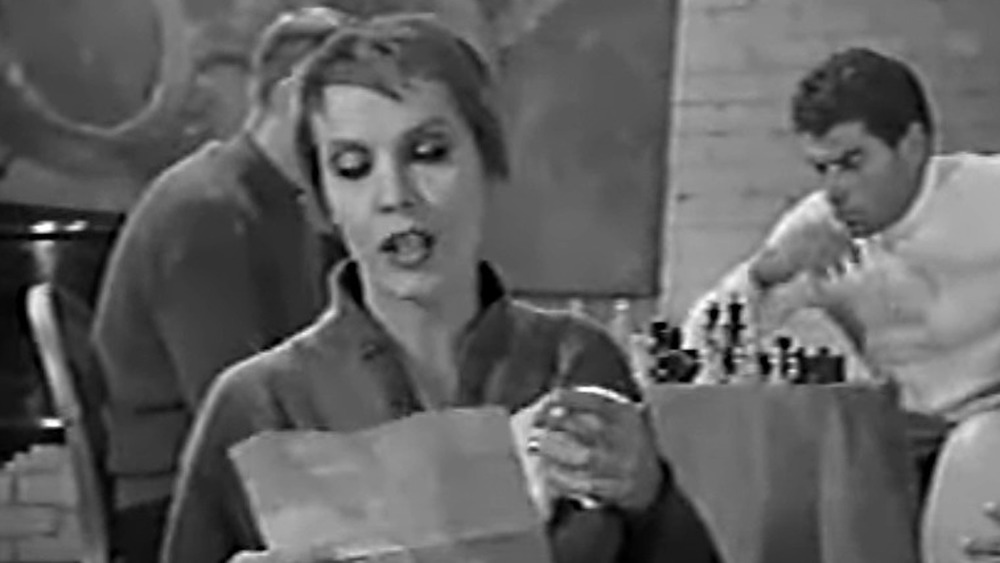

Nurmi would bring Vampira to L.A.'s KHJ-TV, but that revival was short-lived. As documented in Vampira and Me, Nurmi struggled to keep her creepy alter-ego before the public eye and keep herself out of poverty. As Vampira, Nurmi made promotional appearances at car dealership openings and co-starred in a traffic safety film. Soon, Nurmi's prospects in Hollywood dwindled. The woman who was brought to Hollywood to be the next Lauren Bacall was reduced to cleaning friends' houses.

By 1962, she was installing linoleum and working in a restaurant in exchange for food. Nurmi eventually scraped together enough funds to open a small shop she named Vampira's Attic, where she sold handmade jewelry and rubbings of movie star gravestones. Sadly, the business failed, leaving Nurmi in dire financial condition. Relying on friends for food and other necessities, a destitute Nurmi lived in half of a garage where she slept on the floor.

Crazed fans plagued Maila Nurmi

Vampira attracted more than her fair share of unhinged fans and stalkers. As documented in Vampira and Me, in 1955 Maila Nurmi was physically assaulted in public by a disturbed fan. Nurmi's attacker was apprehended by the police. A contemporary newspaper account callously played the violent incident for laughs with the headline, "Clutching Hand Brings Screams From Vampira."

After The Vampira Show ended, Nurmi briefly returned to New York, but encounters with dangerous fans did not end. As recounted by author and horror historian David J. Skal in The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror, Nurmi was nearly murdered by a stalker in her West 46th Street apartment in 1955. Ellis Barber, a 22-year-old man known on the streets as "The Vamp," forced his way into Nurmi's home declaring his intent to kill the actress. Punching her and tearing at her clothing, Barber asked Nurmi, "How long do you think you're going to live?" Fighting back, Nurmi exclaimed, "Until I'm 93!" Nurmi, bearing bruises and lacerations, battled her attacker into the apartment building's hallway and down a flight of stairs before making it to the street and safety. Barber was arrested immediately when he returned to the scene of the assault. As in the prior attack, the press treated Barber's assault on Nurmi as a macabre joke.

Vampira vs. Elvira

In 1981, executives from Los Angeles TV station KHJ-TV approached Maila Nurmi about reviving The Vampira Show. After nearly two decades, it seemed that Nurmi's troubles were coming to an end. According to a 1983 Fangoria article, Nurmi was to consult on the new show providing materials from the original program, such as set photos and scripts. Under her agreement with KHJ-TV, she would serve as an associate producer and do occasional guest appearances as the new Vampira's mother.

Nurmi, however, took issue with KHJ's choice of comedic actress Cassandra Peterson and left the project, taking Vampira with her. KHJ rechristened their new horror hostess Elvira. Peterson as Elvira became a worldwide phenomenon and the most popular horror hostess of all time.

As reported by the Associated Press, Nurmi filed a $10 million trademark infringement suit against Peterson in 1988. "There is no Elvira. There's only a pirated Vampira,″ Nurmi said. ″Cassandra Peterson slavishly copied my product and made a fortune. America has been duped.″ The case was dismissed by the court and, citing lack of representation and funds, Nurmi ceased all appeals. Nurmi's anger over Elvira, perhaps somewhat misdirected at Peterson, persisted until her death in 2008.

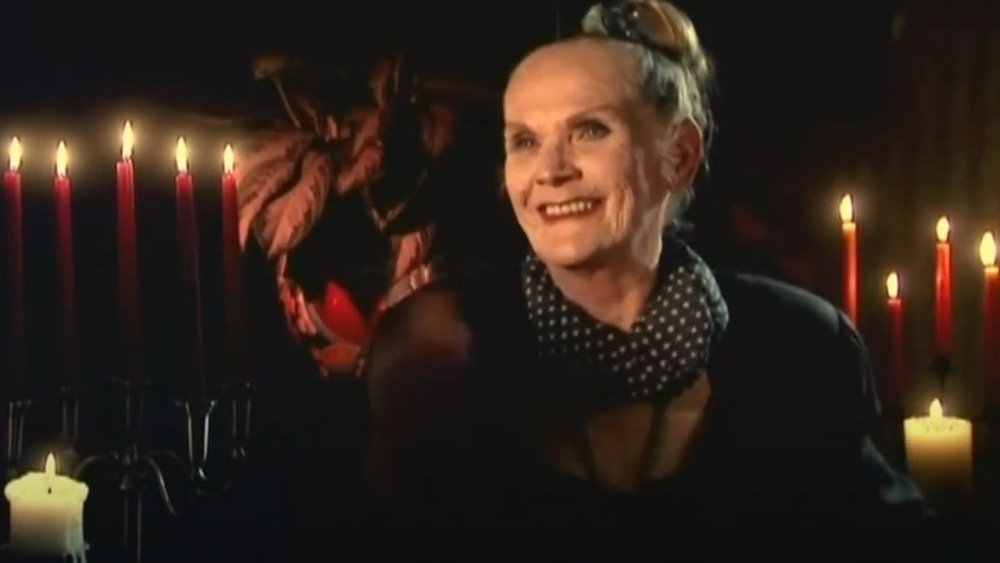

Death of a cult icon

Maila Nurmi died of natural causes in her modest home in Hollywood on Jan. 10, 2008. At age 85, she and her glamour ghoul alter ego had been enjoying a resurgence in popularity thanks largely to increased visibility on the internet and the release of Kevin Sean Micheals' 2007 documentary film, Vampira: the Movie. As Nurmi told KABC-TV in 2000, she was successfully supporting herself by selling drawings of Vampira on Ebay.

Ferried to her grave in a black 1951 hearse, Nurmi was interred at L.A.'s Hollywood Forever Cemetery. Nurmi's small service was limited to a group of close friends — the general public and Vampira fans were barred. Comedian Dana Gould, who had helped Nurmi through rough times, eulogized her with a touching letter in which he expressed his hope to meet her again one day hanging out with James Dean in a heavenly coffee shop.

The undying legacy of Vampira

Although Vampira never made Maila Nurmi rich, her influence on horror and monster kid culture as well as goth and punk fashion is immeasurable. Horror punk icons The Misfits and The Damned have both paid tribute to Nurmi's creation in song. In a 2013 feature, Vogue's Kristin Anderson declared Vampira an "undersung proto-goth goddess" alongside a photo of Nurmi sporting a hybrid devilock/chelsea haircut—styles that would characterize 80s punk and deathrock in the 50s. Eternally ahead of her time, Vampira and Nurmi continue to strike a chord with iconoclasts and outsiders.

When asked by filmmaker R.H. Greene if she was proud of Vampira's legacy, Nurmi replied in deeply personal terms: "Yes, I am. It's my child... You like to feel that your child has succeeded. I birthed her and nourished her and groomed her and sent her out into the world ... I'm glad she succeeded in business."