The Terrible True Story Of The Burning Of The Reichstag

In the aftermath of World War I, it wouldn't be wrong to say that Germany was seeing a lot of change. The Weimar Republic was still basically in its infancy, with the Weimar Constitution going into effect in 1919 and establishing the first attempt at a liberal democracy in Germany. The Reichstag had become the home of the new Parliament, and those Reichstag officials were chosen by a popular vote. A chancellor led the Reichstag, while President Paul von Hindenberg held executive power.

On paper, it doesn't sound bad, but it was going pretty terribly, to put it lightly.

The Reichstag was a mess. No single party held a majority, fragile alliances between parties came and went, and taken together, it led to constant instability. None of that was helped by von Hindenberg dissolving the Reichstag time and time again, ordering re-elections all the time.

The unstable political landscape gave the Nazi Party the perfect place to rise to power, and any history teacher could go on about how and why the Nazis became what they did. But if there was one defining moment in the rise of the Nazi Party, it just might be the burning of the Reichstag.

Rising Nazi power in the Reichstag

The 1920s saw a lot of development in the political landscape of Germany, much of it in favor of the National Socialist German Workers' Party (better known as the Nazi Party). Adolf Hitler rose to the top of the organization — still small at the time — which decided to denounce the Weimar Republic and the Treaty of Versailles (via Smithsonian Magazine).

But the Great Depression changed things. Within Germany, massive social issues started to make themselves known, and that presented a perfect opportunity for the Nazis, whose influence grew country-wide throughout the 1930s. They weren't a small political party anymore, far from it: They'd actually become the second-largest party in the Reichstag. With over 18 percent of the Reichstag vote, they were only behind the Social Democrats. They had three of the 13 cabinet seats in the Reichstag (via Berlin Experiences), but by aligning more closely with other right-leaning parties, their control effectively rose to a third of the vote.

Outside of the pure numbers, they were doing well, too. President Paul von Hindenberg had (albeit reluctantly) named Hitler as the chancellor in the Reichstag, fearing Communist machinations. It seems ironic in hindsight, considering that the Nazis had already infiltrated the police (and knowing the events that would follow less than a decade later). Still, their influence was growing, and with an election coming up, they wanted to take the majority of the seats in the Reichstag.

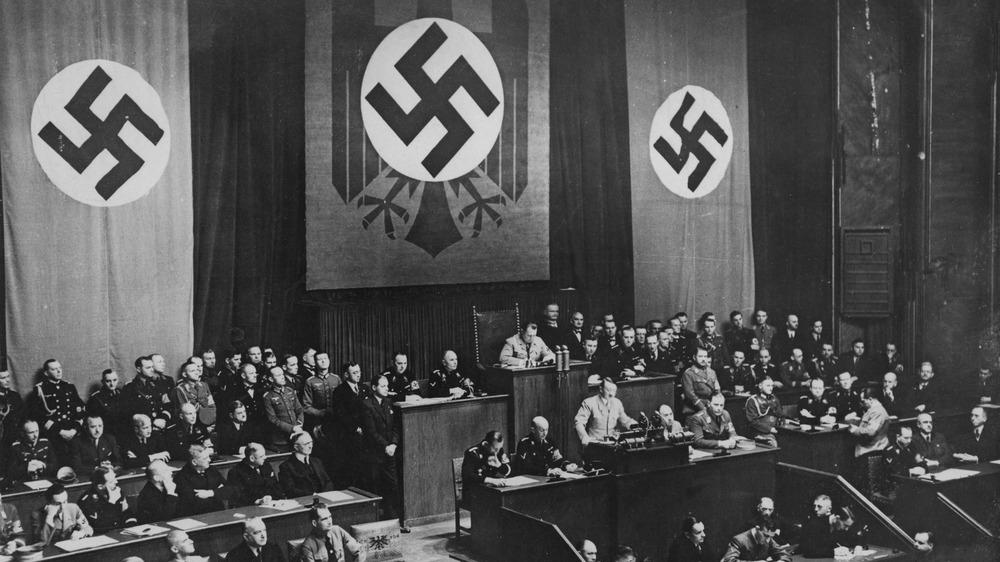

The burning of the Reichstag

It was a snowy evening on February 27, 1933, and, for a while, everything seemed perfectly normal, according to Berlin Experiences. Parliament had already been dissolved by von Hindenberg due to the upcoming elections, slated for March 5, leaving the building just about empty, with only a few guards around, keeping watch.

But it didn't take long for the peaceful reverie to be shattered. A few minutes after 9:00 PM, a young student reported seeing a man breaking some windows, and shortly after that, the Reichstag was set aflame. Firefighters arrived on the scene not long after, but the fire still took hours to put out, and even when everything was over, there was still the more than $1 million in damage that had to be taken care of (via Smithsonian Magazine).

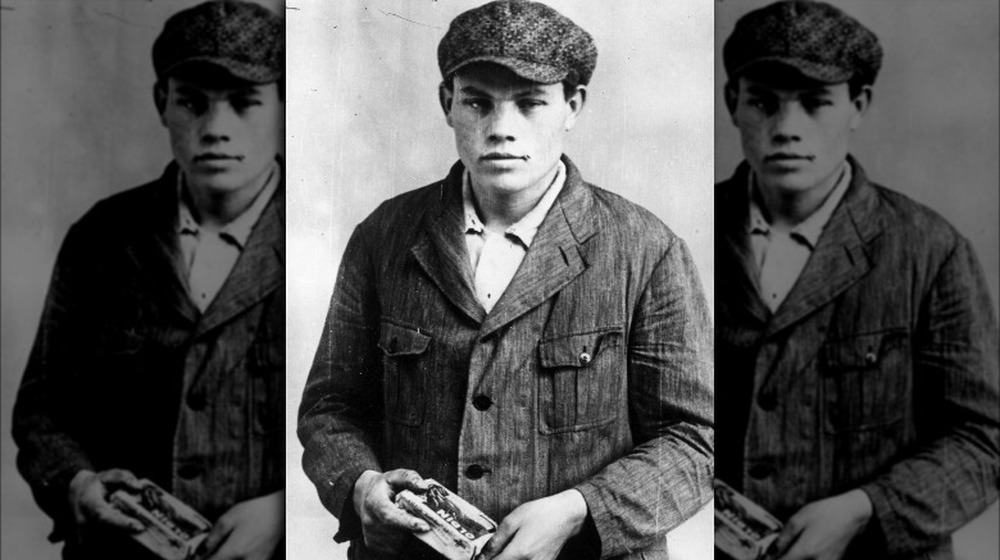

It didn't take long for the authorities to find themselves a suspect: Marinus van der Lubbe (pictured above), a Dutchman who was found near the scene of the crime, in possession of fire-starting materials, and just generally looking exhausted. He was arrested, and once Hitler and other Nazi leaders arrived on the scene, they assumed foul play on the part of the Communists.

The Reichstag Fire Decree

The results of the burning of the Reichstag were immediate and dramatic. At Hitler's urging, President von Hindenberg invoked Article 48 and issued the Decree for the Protection of People and the Reich, more commonly known as the Reichstag Fire Decree, as the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum explains.

This decree was no joke. In essence, it completely removed the rights of the German people, shutting up free press and suspending the autonomy that certain German states enjoyed (via Smithsonian Magazine). Due process just didn't exist anymore, and the police — long since infiltrated by Nazi stormtroopers — could arrest political opponents without reason.

About 4,000 people were arrested because of this act, many of them tortured by the Nazis for information. Members of the Communist Party were detained for no other reason aside from their political affiliations and kicked out of Parliament, despite rightfully winning their seats in the last election.

By the time March 5 came around, the Nazis would end up winning about 44 percent of the vote — still not a majority, even after they'd rounded up all of their political opponents (via Berlin Experiences). But that didn't really matter in the long run. The sweeping suppression of civil rights was more than enough, because, well, most people know what happened next. Genocide and World War II are pretty hard to forget.

The Reichstag Fire Trial

Having found Marinus van der Lubbe at the scene of the crime, the Nazis were pretty ready to have him tried and also to turn the trial proceedings to their advantage. After all, they were in a good position to do so, and the fire had basically served them an opportunity on a silver platter.

Van der Lubbe was believed to have Communist ties, so the Nazis were quick to round up four other known Communists and put all of them on trial (via Berlin Experiences). The idea was basically to have the fire look like a Communist plot against the government, rather than just the work of one man.

Things didn't really go according to plan, though. Van der Lubbe insisted throughout his testimony that he'd acted alone: Even after hours and hours of interrogation, he stuck to that story (via the London Review of Books). So because of that, after multiple months, the court had to rule that van der Lubbe had, in fact, acted alone, acquitting the other four Communists due to lack of evidence. As for van der Lubbe? He was executed — capital punishment that arson wouldn't have warranted, if not for the fact that the Nazis postdated the fire to suit their own desires.

The Reichstag Fire Trial was a PR mess for the Nazis

The Nazis wanted to be able to use the court system as another means to their end. That much seems likely, especially since, shortly after the Reichstag Fire Trial, they set up their own sets of courts that bypassed normal legal procedure and gave whatever verdict they wanted (via the London Review of Books). So to say that four of the five suspects being acquitted was a disappointment is kind of an understatement.

But that wasn't the only problem that came out of the trial. The Nazis wanted so badly to make sure that all the Communists were found guilty that they actually forged evidence, according to Berlin Experiences. Coerced witnesses, fake interrogation transcripts, and a guidebook to Berlin that had supposed proof of a coordinated Communist attack were all offered as evidence — but the court could see through the act. It's not a good look, lying in a legal trial.

Even more infamously, Hermann Göring, the prime minister of Prussia at the time, completely lost his cool. In his statement, he made it obvious that the Nazis had decided instantly that the Communists were the culprits and had no intention of looking for other possibilities. When pushed about that, he started yelling at one of the defendants, purple-faced and threatening violence in a way that international reporters compared to Mafia leaders rather than a prime minister.

The burning of the Reichstag was a convenient way for the Nazis to take power

Less than a month after the burning of the Reichstag and the passing of the Reichstag Fire Decree, on March 23, Paul von Hindenberg passed the Enabling Act, which essentially gave all legislative power to Hitler as the chancellor of the Reichstag (via Smithsonian Magazine). A year later, in 1934, von Hindenburg himself died, giving Hitler the chance to combine the offices of chancellor and president, and the Nazi Germany that everyone reads about in their history books was born.

And that chain of events has the burning of the Reichstag to thank. Prior to the fire, the Communists had been a major obstacle to the Nazis' rise to power. They actively wanted to introduce a Communist state to Germany and had actually gotten 17 percent of the vote in the November 1932 election (via the London Review of Books). It wasn't a majority by any means, but they'd actually increased their support in that election, the same one in which the Nazis' support had decreased. Plus, the Nazis were concerned enough about the Communists that they'd already tried to discredit them, "discovering" evidence of plans to attack public buildings. (They were fake.)

With the burning of the Reichstag, suddenly, the Nazis had consolidated power and all but eliminated their political opposition in one fell swoop. Correlation doesn't equate to causation, but it does arouse suspicion.

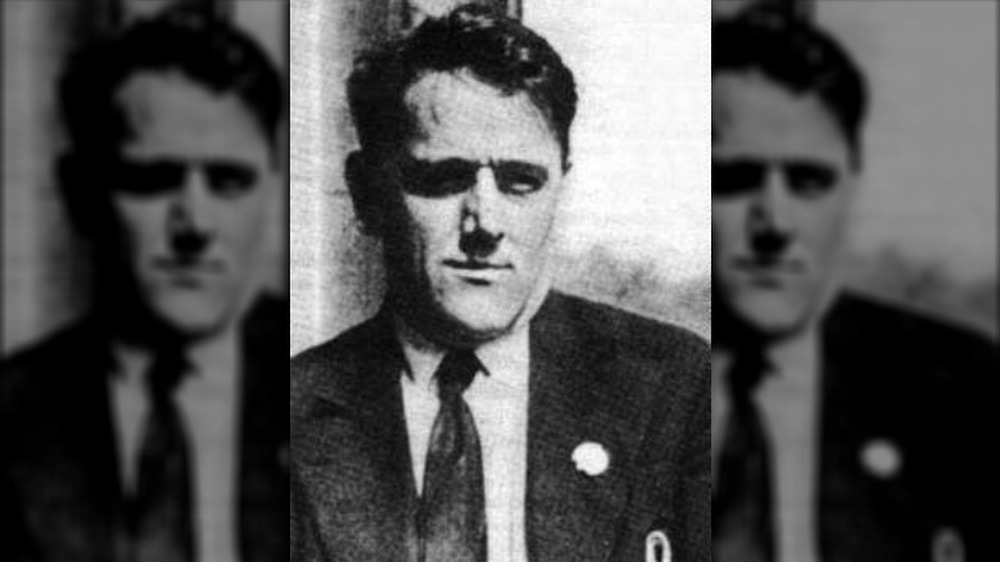

The Communist Party definitely thought the Nazis were involved in the burning of the Reichstag

Unsurprisingly, the Communists weren't about to admit to any involvement in the burning of the Reichstag. Far from it. They would actually go on to do the complete opposite, suspecting the Nazis of starting the fire in the Reichstag themselves and conducting their own investigation, headed up by Willi Münzenberg (pictured above). That investigation eventually led to a full book, published in the same year as the fire, called The Brown Book on the Reichstag Fire and Hitler Terror (via Smithsonian Magazine).

The book narrates through many instances of brutality and disregard for human rights which were committed by the Nazis (via the London Review of Books). It makes it easy to believe that the Nazis might have been willing to burn down the Reichstag just to further their own agenda. But it also pushes the Communist theory that van der Lubbe was actually a Nazi pawn, rather than a Communist one. They believed that the Nazis had entered the Reichstag through a secret tunnel, set the building ablaze, and left van der Lubbe behind to take the fall.

In the end, the book did get some traction because the theory isn't entirely far-fetched. Even as early as the night of the fire, some people suspected Nazi involvement: A reporter for a German publication sent his editor a very similar story, implicating Nazis who'd escaped through a secret tunnel (via Berlin Experiences).

People believed that van der Lubbe burned the Reichstag alone

Despite theories of Nazi involvement and even the court suspecting more than a single arsonist (via Berlin Experiences), the most well-accepted explanation was simply that Marinus van der Lubbe set the Reichstag fire on his own.

The Nazis themselves apparently didn't have prior knowledge of the attack. Joseph Goebbels was with Hitler on the night of the fire, and upon getting a call that the Reichstag was burning, he initially thought it was a joke (via The Guardian). In his testimony, he claimed he hung up and didn't believe the news until getting a second call.

And besides, van der Lubbe insisted that he was alone (via the London Review of Books). His panting at the scene would also seem to corroborate that story: Why would he be panting if he had an entire group to help him? Plus, he'd already tried in the past to burn other buildings. It was his form of protest, so the Reichstag could've just been one of his many targets. And even the lack of full fingerprints made it appear that the Nazis weren't involved. They easily could've — and had, in the past — planted evidence. Why not this time?

And to complicate things more? Van der Lubbe had officially left the Communist Party a couple years earlier, making Nazi involvement seem less likely. If the goal was to frame the Communists, why not use someone who was officially still a member?

Later evidence made people question van der Lubbe's level of involvement

Despite the Reichstag burning in the 1930s, the theorizing and speculation continued for decades. A major factor in that speculation carrying on so long (aside from the intrigue of a mystery) is actually the fall of the Berlin Wall, which made information available to the Western world (via History Extra).

Historian Benjamin Hett learned about that information and began to argue that Marinus van der Lubbe couldn't have been the sole perpetrator of the fire. The Reichstag's Plenary Chamber was incinerated in about 15 minutes, and for one man to accomplish that with nothing more than some lighters and a few matches is hard to imagine. And besides that, the fire seemed to have been started with oil or some flammable liquid — not the kind of fire-starting materials that van der Lubbe had on his person.

The questions get even stranger, though. According to witnesses at the trial, van der Lubbe was nigh-incoherent on the stand (via Berlin Experiences). Slumped over, confused, and forgetful, van der Lubbe's behavior has become its own question, with some believing that his symptoms align with those of potassium bromide poisoning. It would've been a hard poison for van der Lubbe to detect — it's kind of similar to normal table salt — and it would've basically neutralized him as a threat during the trial, leaving him incapable of implicating anyone else, Nazi or Communist.

It's hard to take any of the theories at face value

As easy as it is to create new theories about the burning of the Reichstag, it's just as easy to discredit others. Fritz Tobias is the man who is largely credited with popularizing the theory that Marinus van der Lubbe worked alone, but Benjamin Hett argues that Tobias might not be the most unbiased source (via History Extra). He found that Tobias was formerly a German intelligence officer who, after the war, kept up friendly relations with ex-Nazis: If nothing else, it seemed to Hett like there was some kind of ulterior motive.

But then, Richard J. Evans argues against Hett's interpretations, saying that Hett ignores information that goes against his theories, like friends of Tobias who supported left-leaning policies (via the London Review of Books). So maybe Tobias wasn't necessarily just covering up Nazi involvement in the burning of the Reichstag.

To make things even more confusing, this whole mess of pointing fingers has led to a lot of false information. Journalist Edouard Calic wrote a book called Unmasked in order to prove the Nazis' part in the fire, including an interview with Hitler in 1931 where he mentioned those exact plans. The book was proven to be almost entirely made-up. But undeterred, Calic went on to form the Luxembourg Committee in the 1970s, intending to prove the Nazis' part in the fire. New evidence was unearthed, most of which was, once again, found to be fake.

The burning of the Reichstag is still a mystery

According to The Guardian, a waiter testified to having seen Marinus van der Lubbe at a restaurant with three of the other four Communists tried in the Reichstag Fire Trial. But seven other waiters and the manager contradicted that, saying that they had never seen van der Lubbe before. However, they did see a different man who bore some resemblance to van der Lubbe: Several of them were sure of it.

Then there was an account from a police officer on the night of the fire who, upon immediately investigating the building, ran into men in new police uniforms coming up from below (via Berlin Experiences). The timing meant those men would've had to have been in the building before any officers arrived. Why were they there? What were they doing in brand-new uniforms? No one is sure — the men suspected of being involved were killed in the Night of the Long Knives.

Even as late as 2019, a report from an ex-SA member said that he and a few others drove van der Lubbe to the Reichstag on that night, only to find the building already burning (via DW). All the men were sworn to silence and most were killed, but if the story is true, was van der Lubbe even involved at all? And why was he being driven to the Reichstag?

Basically, the entire story is a mystery wrapped in an enigma, surrounded by strange details and few solid answers.