Famous People Who Survived The Holocaust

When genocide happens on a global scale, it can come with numbers so high that they're impossible to imagine. Take World War II, and the Holocaust. The Economist puts it this way: If you took each one of the more than 6 million dead and read a blurb about each one of their lives, spending five minutes on each person, you'd have enough reading material to last 90 years.

When it comes to survivors, they aren't just the people who were sent to concentration camps: Washington Jewish Week says they're also the ones who were sent to ghettos, who fled their homelands, or who spent years in hiding. They were also the children whose parents sent them away, in hopes of keeping them safe.

Among those trying to make sure that what happened to the world's Jewish population isn't forgotten are many of the survivors themselves: Famously, survivor Simon Wiesenthal made it his mission to make sure the Nazis who escaped justice were held accountable. Other survivors include some very famous people who grew up in the most unimaginable horror and went on to change the world in their own ways.

Branko Lustig: Tell the story about us

Schindler's List remains one of the most powerful movies ever made about the atrocities — and individuals — of World War II, and that's not just because of Steven Spielberg's storytelling abilities. The film's producer, Branko Lustig, was a Holocaust survivor who spent two years in Auschwitz before being moved to Bergen-Belsen, where he was present for the camp's liberation. He weighed just 66 pounds, despite being 12 years old, and had typhoid.

The Jewish Virtual Library says that his survival came down to chance: He had been in Auschwitz when a German officer heard him crying. The officer, it turned out, was from the same town he was and knew his father — who died in 1945.

According to the Independent, it was a scene that unfolded not long after his arrival at Auschwitz that made him determined to survive, and to tell the world what he'd seen. Lustig was front and center for the public hanging of seven people and recalled: "Moments before they were hanged, before the bench was kicked out from them, they all said as one: 'Remember how we died. Tell the story about us.'"

And he did — his long film career didn't see him working on just movies like Gladiator and Black Hawk Down but also on Sophie's Choice and the WWII TV series Winds of War and War and Remembrance. Lustig died in 2019.

Dr. Ruth Westheimer: saved by the Swiss

Many might know her as Dr. Ruth, but when she was born in 1928, she was given the name Karola Ruth Siegel. The German-born Siegel (who would later marry and become Ruth Westheimer) has talked often about her early life, when her family was destroyed by the events leading up to World War II.

According to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, Westheimer last saw her father on November 10, 1938. That was day after Kristallnacht, a wave of violence, destruction, and killing that broke out across Europe on the orders of the Nazi party. Westheimer had watched her father's arrest, and it wasn't long afterward that her mother — knowing that Kristallnacht was just the beginning — arranged to have her taken to Switzerland. She left as part of the Kindertransport mission, which the BBC says was responsible for shuttling around 10,000 children out of Nazi-controlled territory.

In her single suitcase was a special washcloth, packed by her grandmother. When she spoke in support of Naples' Holocaust Museum in 2020, she recalled (via the Naples Daily News) that she still has the washcloth and doesn't "let it out of [her] sight."

Westheimer was raised in a Swiss orphanage and never learned what happened to her parents — although she's fairly sure they died in Auschwitz. She says, "I don't want to be called a survivor of the Holocaust. I want to be called an orphan of the Holocaust."

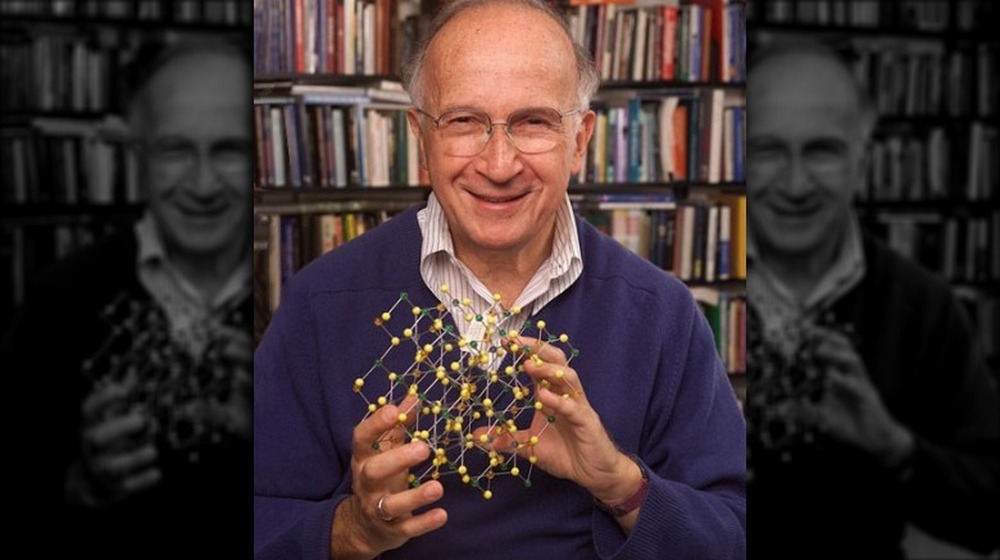

Roald Hoffman: Good people save the world

Roald Hoffman won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1981, and according to the Science History Institute, he got it for "theoretical work on the course of chemical reactions." He's also a poet, philosopher, and a Holocaust survivor who was born in Poland in 1937.

According to his Nobel Prize biography, his entire family was sent first to a ghetto. That was followed by a move into a labor camp, and in 1943, his father risked everything to organize an escape for young Hoffman and his mother, after which they were hidden from the Nazis by a Ukrainian family. After liberation by the Soviets, they lived in Poland, Czechoslovakia, Austria, Germany, and finally the U.S., where he learned to speak his sixth language: English.

In 2017, Hoffman gave a talk in Penn Hillel about his experiences in the war, sharing (via The Daily Pennsylvanian) the fact that it was only much later that he learned his father had been tortured and killed in the camp he escaped from. Still, he focuses on the positive: "Almost everyone who survived, almost everyone has a good story to tell, and in it featured good human beings... Saviors. Because it was impossible to survive without help from somebody, and there are good people in any times, and those good people save the world."

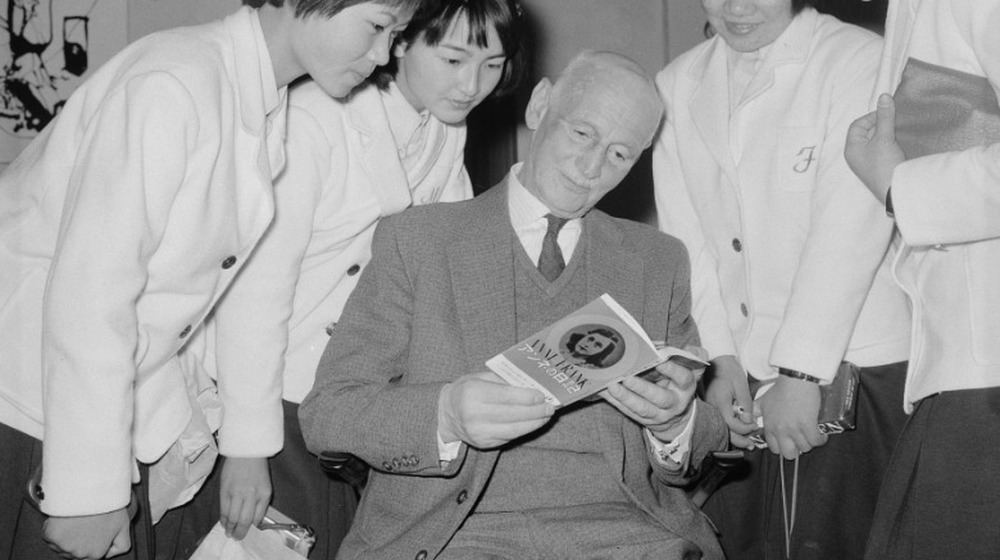

Otto Frank: A world turned to wilderness

Anne Frank wrote (via The Washington Post): "I see the world gradually being turned into a wilderness. I hear the ever-approaching thunder which will destroy us too [...] yet if I look up to the heavens I think that peace will return again."

Copies of Anne Frank's diary have sold somewhere in the range of 14 million copies, and at first, her father had no intentions of publishing what he called "Anne's last will and testament." But that changed as he realized how necessary it was to help preserve the memory of what had happened.

Frank had fought for Germany in World War I, and The Guardian notes that after his life as an upper-middle-class banker fell apart in the 1930s, and after attempts to keep his family out of Nazi hands failed, he spent six months in Auschwitz. (Anne died in Bergen-Belsen.) By the time the Nazis fled before Allied armies, he was too sick to be taken on the death march from the camp and was liberated in 1945 — just months before what would have been Anne's 16th birthday.

He held out hope for her survival until July 18, 1945 — the day he saw her name on a Red Cross list of the dead. Frank died in 1980, survived by his second wife and stepdaughter, who also survived Auschwitz.

Robert Clary: From real concentration camp to fictional POW camp

When it comes to unlikely sitcoms, Hogan's Heroes is up at the top of the list with a setting that puts all of the madcap action right in the middle of a WWII German POW camp called Stalag 13. Forbes says that while it might be a tough sell with modern audiences, it was a hit when it premiered in 1965 — and even stranger, one of the main cast members was a Holocaust survivor.

French Corporal Louis LeBeau was played by Robert Clary, who was just 16 years old when he, along with most of his family, was taken from his Paris home and put into the Nazis' network of concentration camps. He spent some time working in a shoe factory and recalled (via The Spectrum), "The first time I saw a hanging, it was petrifying. They would have people for nothing most of the time, and the beatings were unbelievable."

Clary also survived a death march from Blechhammer to Buchenwald, a days-long march where around 2,500 people died along the route. He was at Buchenwald for the 1945 liberation, and according to the Jewish Virtual Library, he was the only member of his family who had survived the camps (and later found some siblings who had avoided capture).

Hogan's Heroes, he says, wasn't traumatic — it was a very different experience, and he found that it was only after he started talking about it that the nightmares stopped.

Roman Polanski: one of the most joyful moments of my young life

Director Roman Polanski's disgrace is no secret: He fled the US in 1978 after entering a guilty plea to charges of "unlawful sex with a minor." The Associated Press notes that he now lives in France, and when he went to Poland in 2020, it was one of the few countries he was actually able to visit. The occasion had nothing to do with the charges that tarnished his reputation: He was going to attend a ceremony honoring a Polish couple who had hidden him from the Nazis during WWII.

Polanski, who was born in France in 1933, moved to Poland with his parents in 1936. According to The Guardian, the entire family was sent first to Krakow's ghetto, where they lived for several years. They came for his mother first, and he recalled his father telling him the news: "He burst into uncontrollable sobs. I didn't cry right away and I begged him to stop."

Polanski's mother was taken to Auschwitz and ultimately died there. His father was also deported to the camps, but Polanski escaped to the home of Stefania and Jan Buchala, who Yad Vashem honored with the title Righteous Among the Nations after Polanski's request. Polanski also recalled the moment when he knew the war was coming to an end: "I looked up, and these were the American bombers coming, hundreds of them. It was one of the most joyful moments of my young life."

Simone Veil: I have survived worse than you

Simone Veil's list of achievements is incredibly long: Not only was she the first female president of the European Parliament, but she was a champion of women's rights (and birth control) and wrote French abortion law in a fight that made her a target for far-right extremists. According to Vox, it was during one confrontation that she was heard yelling over the crowd and the fighting: "You do not frighten me! I have survived worse than you!"

And she had: In 1944, she and her family were taken from their home. Veil was first taken to Auschwitz (along with her mother and sister), and then the three women were rounded up yet again for a death march to Bergen-Belsen. Veil's mother died there, and she never knew what happened to her brother and father.

Veil later drew on her experiences in the camps to stand before the governments of Europe and call for unification. In 2005, she recalled (via The Guardian), "Sixty years later I am still haunted by the images, the odors, the cries, the humiliation, the blows, and the sky filled with the smoke of the crematoriums." Of the 400 children deported from the Nice region, she was one of 11 survivors. Veil died in 2017.

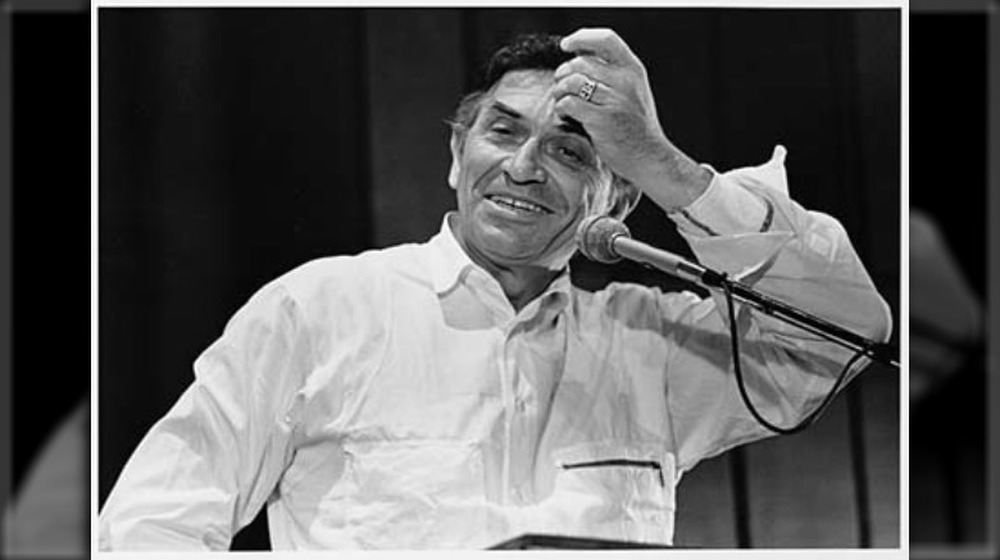

Bill Graham: I've asked very little about my mother [and] father

It's entirely possible that without Bill Graham's tireless promotion of groups who would become some of the most well-known names in music history, that history would look very different. From Bob Dylan to events like LiveAid, Graham had a hand at getting them all front and center, but he wasn't always known as Bill Graham. That, says The Jewish News, was just a name that he picked out of a phone book when he emigrated to the U.S.

The Guardian says that his birth name was Wulf Wolodia Granjanca, and he was a German-born Jew and an orphan of the Holocaust. In 1940, his mother told eight-year-old Graham and his sister that they were going to go on a vacation — and that, says The Jerusalem Post, is the last time they saw her. The Bill Graham Foundation says when France became occupied territory, he was constantly on the move alongside a group of Red Cross workers. Two years after leaving home, his sister developed pneumonia, and they separated. He never heard from her again.

Graham traveled for years until finally finding his way onto an ocean liner bound for America. He found out later that his mother had been killed on the way to Auschwitz and once shared that he had few memories of his parents.

Tibor Rubin: I wanted to show my appreciation

Corporal Tibor Rubin has a singular honor: According to the Association of the United States Army, he's the only Medal of Honor recipient who's also a Holocaust survivor.

The National Medal of Honor Museum says the Hungarian-born Rubin was 13 years old when he was sent to Austria's Mauthausen concentration camp. He spent 14 months there, and when liberation came on May 5, 1945, he met the men of the 11th Armored Division. Tragically, The Hall of Valor Project notes that he was the only one of his family to survive.

Rubin became determined to repay those who had fought — and died — for his freedom, so he headed to the U.S. and joined the Army, 1st Cavalry Division. He later recalled: "When I came to America, it was the first time I was free. It was one of the reasons I joined the U.S. Army, because I wanted to show my appreciation."

Rubin was deployed in the Korean War, where he not only distinguished himself in combat multiple times but was captured, taken to a Chinese POW camp, and remained there alongside his fellow soldiers — in spite of a Chinese offer to return him to Hungary. There, his survival skills were credited with saving the lives of around 40 soldiers, who were ultimately freed. He was awarded the Medal of Honor in 2005, with some of the men he'd saved in attendance.

Elie Wiesel: Messenger to mankind

Elie Wiesel won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986 and was a journalist, author, lecturer, professor, founder of the International Network of Children of Jewish Holocaust Survivors ... and so much more.

The Nobel committee called him "a messenger to mankind," and The New York Times explains that's largely because in the aftermath of the war, there was something incredibly important that was missing: a voice, to remind people what had happened and how it had changed the world. Wiesel became that voice, first with his 1960 book about what he'd seen while he'd been a prisoner of the Nazis.

Wiesel grew up in one of the ghettos of Sighet and recalled watching everyone he had ever known marched out until he, too, was sent onto a cattle car destined for Auschwitz. He would later write, "Never shall I forget that night, the first night in camp, which has turned my life into one long night, seven times cursed and seven times sealed."

From Auschwitz to the labor camp Bruna, it was then on to Buchenwald, where his father died — and where he wished he, too, would join him in death. Liberation came just a few months later, and it was then that he knew he had survived to tell the story that so many others could not. Wiesel died in 2016.

Imre Kertesz: those 20 minutes

Hungarian Imre Kertesz was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2002, for his novels that the Nobel committee described as (via The Guardian): "uphold[ing] the experience of the individual in the face of a barbarian and arbitrary history." When The New York Times announced his death in 2016, they wrote that he had been "dumbfounded" by the Nobel Prize award — for years, his semi-autobiographical works had been largely overlooked. Fortunately, though, his work, and his story, was finally recognized.

Kertesz had been a 14-year-old student when he was apprehended and taken to Auschwitz, and it was some invaluable advice that saved his life. He was told to say he was a laborer, not a student: That lie got him sent to a forced labor camp instead of the gas chambers. He was later transferred to Buchenwald and was there for liberation in 1945 — after being declared dead in camp records. Eerily, history repeated itself: When Hungary became Communist, he once again hid his academic ability to avoid being sent to a labor camp.

In his Nobel acceptance speech, he spoke about the 20 minutes he'd stood on the Birkenau arrival platform, waiting for someone to decide if he was going to live or die. His memory was very different from what he saw in photos, and he said it was that moment when "I gained an insight into the mechanism of horror."

Primo Levi: It was my good fortune

Primo Levi wrote one of the most lauded books about life inside a Nazi concentration camp, and the first words seem the most unlikely: "It was my good fortune." According to The Atlantic, Levi isn't just a writer. He's up there among the greats — and he was writing from personal experience.

The "good fortune" he explains is that he wasn't deported until 1944, a time when it wasn't just approaching what would be liberation but also when the Nazi war machine needed laborers. Levi was kept alive and sent to Auschwitz, where he was put to work in a rubber factory. He was among the few who left the camp: Of the 650-odd people who were on the train with him, there were only around 20 survivors.

When Levi began to write, he explained, "I am alive, and I would like to understand you so that I can judge you." His book If This Is a Man remains one of the most powerful on the Holocaust, one that tells a story for those who no longer have a voice. Levi died in 1987, after falling down stairs in his home in Italy, according to the LA Times.