What It Was Really Like Being A World War II Codebreaker

The image of a codebreaker trying to unscramble a seemingly meaningless string of numbers and letters in the dim light of a bunker comes from World War II. But during and after the war, those people we now understand as some of the most important behind-the-scenes heroes of the war effort were as secret as the ciphers they were trying to decrypt. It's only recently that we've started to uncover what it was really like being a World War II codebreaker.

Technically, by the time World War II broke out, the people working to decipher messages sent by other nations weren't codebreakers. By then, the major powers had moved away from codes that simply replaced one word with another, in favor of multilayered ciphers that required keys, machines and lots of time to unscramble. The U.S. had also started to evolve its early versions of code making and breaking into a larger operation. But it still faced major challenges, including finding, training, and threatening new recruits, and collaboration across branches.

The army improved its code breaking for World War II

The American code breaking operation during World War I was run by two civilians: married couple and pioneering cryptologists William Friedman and Elizebeth Smith Friedman. In 1929, the Army decided to beef up this scrappy operation: the Army Signal Corps created the Signal Intelligence Service (SIS) and appointed William chief cryptologist. (Elizebeth was soon busy working for the Coast Guard, busting bootleggers and later Nazis in South America.) William recruited six assistants, including three junior cryptologists: Frank B. Rowlett, Abraham Sinkov, and Solomon Kullback.

The initial job of SIS was to train cryptologists for future war work. As the National Security Agency (NSA) — a later incarnation of the SIS — explains, the SIS's initial purpose was to create new ciphers for the U.S. army's use, but William insisted on training his staff in cryptanalysis too. This proved useful, because when World War II started, the department was involved in code breaking. The cryptologists mainly worked on diplomatic ciphers (rather than military ciphers), mostly from Japan.

SIS was based in Arlington, VA, in a girls' school commandeered by the military. SIS translator Bernard A. Weisberger remembered sleeping "in hastily built wooden barracks" which were still being erected to keep up with the ever-increasing staff. The seven-person department had grown to 336 by December 7, 1941, and 10,000 by V-J Day on August 14, 1945. The SIS was renamed the Signal Security Agency in 1943, and the Army Security Agency in 1945.

The Navy had multiple code breaking operations

Whereas SIS was the core of the U.S. Army's code breaking operations, the Navy had a few different departments working on cryptology. There were three processing centers where Naval cryptologists worked. The so-called Cast unit was based on an island in the Philippines called Corregidor; Station HYPO was in Hawaii; and the main Naval cryptology base, OP-20-G, was based in Washington, D.C., at Nebraska Avenue. Similar to SIS's headquarters, the facility had previously been a girls' seminary. It later housed the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), until 2019. According to the NSA, by the end of 1941, the Cast unit had 76 people, Station HYPO had around 80 to 90 total, and OP-20-G had 300.

Throughout the '30s there had been a less-than-productive rivalry between the Navy and the Army over which communications each branch would be responsible for cracking. They worked on Naval and Army communications respectively, but by the end of the decade, the sheer volume of Japanese diplomatic messages being intercepted meant they had to share. Ultimately, in August 1940, it was decided that the Navy would take charge of deciphering Japanese diplomatic messages on odd days of every month, while the Army would be responsible on even days.

As the Library of Congress reports, unlike Army codebreakers, Naval cryptologists had to attend boot camp after completing a code breaking course, and were then recruited into the military. From 1942, that included female recruits.

The code breakers worked on many codes

Code breakers in the American military mainly worked on Japanese codes, since they were better poised to intercept this traffic. The Japanese Army, Navy, and diplomats used many different codes throughout the war. For example, by 1942, in addition to its main cipher, the Navy was using around 14 other codes to relay information of relatively minor importance.

The Japanese codes were named after colors. The first Japanese diplomatic machine cipher, named Red, was produced using a machine the Navy named A. But in 1939, the major Japanese embassies around the world switched to using a different and more complicated machine, subsequently named B, that produced a cipher named Purple. There was also Coral, which was used by Naval attaches.

From 1939, the Japanese Navy used a cipher for military messages that the Americans nicknamed JN-25. Cryptologists at Station HYPO in Hawaii eventually managed to crack most of the cipher in 1942, with help from IBM punch-card machines that sped up the process of sorting through thousands of messages looking for patterns.

The American military also worked on possibly the most famous code from World War II: the German code Enigma. In 1942, the Navy started building its own bombe machine — the machine that helped cryptologists in Britain's Bletchley Park crack the cipher. According to the NSA, by spring 1944, OP-20-G had 96 bombes running around the clock, breaking German U-boat communications.

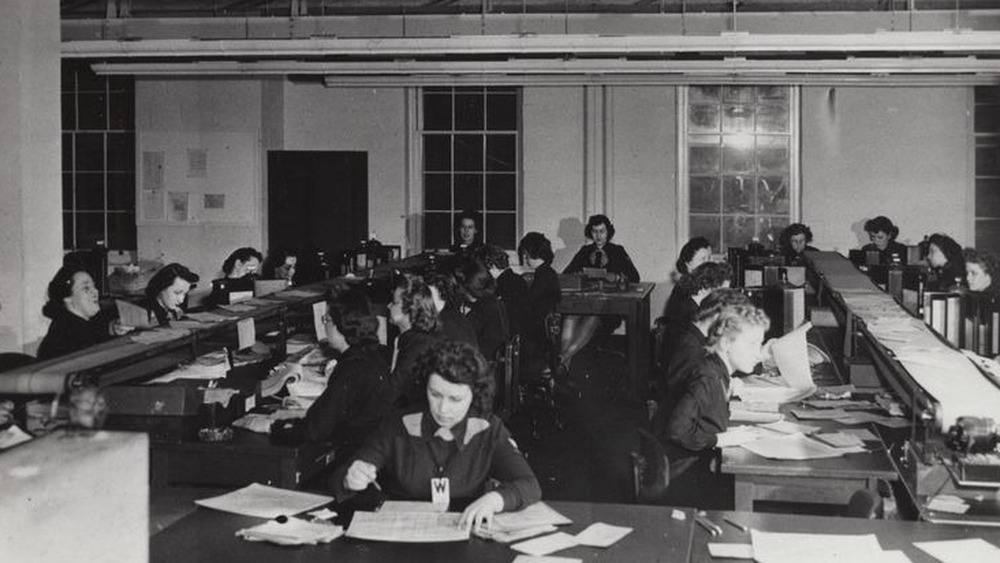

Most codebreakers were women

Thanks to stories from World War II of codebreakers whose efforts saved countless lives, today we often think of codebreakers as geniuses. But during the war, codebreaking was seen as a menial, boring job best left to people who weren't needed elsewhere. Specifically, women. As the Denver Post reports — based on figures from Liza Mundy's book Code Girls — 11,000 women worked as codebreakers for the U.S. military during World War II, eventually making up 70 percent and 80 percent of codebreakers in the Army and Navy, respectively.

A few women worked in cryptology from its start in the U.S. In addition to Elizebeth Friedman, Agnes Driscoll worked for OP-20-G from 1918 throughout World War II, and was integral in cracking several key Japanese ciphers, including JN-25. But recruitment of women increased dramatically right before and after Pearl Harbor. In 1942, President Roosevelt established the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES), the female Navy corps, and many WAVES went on to work at OP-20-G, running the bombe machines.

The women saw codebreaking not just as a civic duty to support the war effort, but also as a way to do something interesting. Most had advanced education but very few opportunities to do anything with it. As Mundy told CNN, there was a hope that if the women could prove themselves during the war, colleges like MIT and Columbia would be more willing to take on female graduate students.

A love of puzzles was the first essential trait of a codebreaker

When looking for codebreakers, the Army and Navy tried to find people with a natural aptitude for tackling complex puzzles. Even before the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, they were looking for recruits. That year, certain students from elite women's colleges were invited to secretive interviews, where they were asked two things: "Do you like crossword puzzles and are you engaged to be married?" As the Library of Congress reports, a job advertisement around the same time stipulated: "Candidates must be highly skilled in math and linguistics, willing to relocate and able to keep a secret to the death." It also specifically targeted single women.

The recruitment drive particularly focused on school teachers. Partly this was because it was one of the few jobs available to college-educated women. But many of the male recruits also left teaching jobs to become cryptologists, including William Friedman's first three SIS hires, Rowlett, Sinkov and Kullback.

Perhaps surprisingly, not all of the codebreakers had backgrounds in languages and math. For example, Elizebeth Friedman had majored in English literature at Hillsdale College, MI. Ann Caracristi worked for the SIS under Kullback during the war, and would later be Deputy Director of the NSA. As she told an interviewer, she majored in history and English: "I was lucky enough to be able to work on problems... they did not require a great deal of math, really; they required a great deal of ingenuity."

Code breaking was tedious and sometimes emotionally challenging

The men who brushed off code breaking as too boring and frustrating to bother with were right about the nature of the job, even if they underestimated how difficult it was. Especially by World War II, when codes had been replaced with multilayered ciphers that were next to impossible to solve — at least in reasonable time — without machine assistance.

Most of the cryptologists spent their days going through sequences of code, looking for patterns. Sometimes the messages were long out of date, but cracking them could lead to a breakthrough in current iterations. It was often very hot and stuffy, as Caracristi remembers, and the days and nights were long, with codebreakers working in shifts around the clock. Much of the time, you wouldn't be able to crack that shift's ciphers: a high tolerance for failure was an essential trait of codebreakers, Mundy wrote in Code Girls.

The job could also be surprisingly emotional. Judy Parsons worked at OP-20-G on the Enigma code, deciphering messages from German U-boats. She told CNN that in addition to military dispatches, they often read personal notes and got to know the different senders. In particular, Parsons remembered reading a message from a German U-boat captain who had just learned that his wife was pregnant — and hearing that his submarine had been sunk just days later. "I felt so bad about that because he'll never know his father," she said.

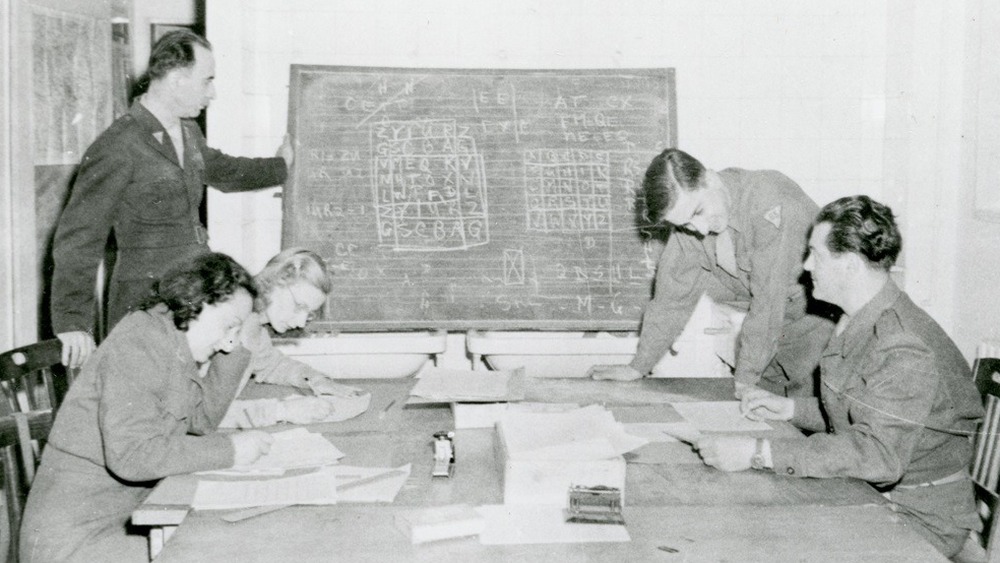

Code breaking took the effort of multiple departments

Cryptologists were just one part of the codebreaking efforts of World War II. There were also people intercepting the messages, and others who sorted through them and fed them into the IBM machines. OP-20-G and the SIS also scoured the country for people who could translate the messages once they'd been deciphered. This was especially important and challenging when it came to Japanese — the language of most of the messages the military was working on — since very few Americans spoke the language. Ironically, the majority of those who did were treated with suspicion and would soon be imprisoned in internment camps.

Bernard A. Weisberger was a student at Columbia when the war broke out, and enrolled in a crash course in Japanese. Writing for American Heritage, he recalled working into the summer after his degree course finished, taking classes for seven hours a day, five days a week, and topping that up with hours of homework. He was recruited to the SIS, where he translated partly deciphered messages written in the Purple cipher. "I could not believe that a skinny 20-year-old kid from Queens was translating material that would become part of a top-secret daily summary," he wrote.

And don't forget those in the field. The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) sent officers to "borrow" ciphers from the Japanese consulate. And on October 30, 1942, two sailors died recovering documents from a sinking U-boat that ultimately led to a break in Enigma.

Female codebreakers faced discrimination

Even though women were the majority of codebreakers, they still faced sexism at their jobs. They were paid 25 to 30 percent less than their male peers, were assumed to be less capable of keeping secrets, and were expected to be happy to do tasks men found boring. The Navy in particular struggled to cope with the incoming WAVES. In an interview for the Library of Congress, former Navy codebreaker Frances Scott (then Lynd) recalled that the women were explicitly banned from talking about period pain: "The Navy did not give you any kind of dispensation for a monthly period. You were supposed to be women who didn't have problems in that direction."

Somewhat ironically, the Navy was also skittish about pregnancies, as Code Girls author Liza Mundy explained to CNN. Any of the women who became pregnant were forced to resign. "It was very hard... because they loved the work and suddenly had to leave. Obviously, men did not have to leave if their wives got pregnant," Mundy said. Another irony: as the Washington Post reports, abortions were also cause for dismissal. As was a sexual relationship with another woman.

The letdown continued after the war, when the majority of the women were expected to step aside and leave cryptology jobs to the returning men. Ann Caracristi recalled accepting this at the time as "patriotic duty," but soon realized that working a "regular" job "paled by comparison with the excitement of working in the cryptologic business." She eventually joined the NSA.

The code breaking units were racially segregated

The U.S. military was segregated throughout World War II, and continued to be so even after July 1948 when President Truman signed Executive Order 9981, officially ending the practice. Mundy told CNN that the Navy wouldn't even hire Black codebreakers, even after the WAVES finally started to recruit Black women in 1945. The Navy also wouldn't hire Jewish codebreakers.

The Army's SIS did hire Black and Jewish codebreakers, the latter including Friedman himself: his family had emigrated to the U.S. to escape antisemitism in Russia. Of his three original hires, highly esteemed cryptologists Abraham Sinkov and Solomon Kullback were also Jewish.

Less is known about the experiences of Black codebreakers, who were mostly women and who worked in a segregated department separated from their white colleagues. It appears that they worked on deciphering messages between enemy governments and private companies such as Mitsubishi. Mundy also told CNN that she believes that like the white codebreakers, the Black codebreakers probably worked as schoolteachers and went to esteemed historically Black colleges. "Washington had a very strong (though segregated) school system, it had Howard University — there would have been no dearth of smart and accomplished African American women to recruit from and who could have done this code-breaking work," she said.

The Navy and Army codebreakers had some major victories

Some of those frustrating cipher-cracking sessions ultimately paid off with military victories. The most famous of these was the thwarting of the Japanese Navy in the Battle of Midway, thanks to the cracking of JN-25. By April 1942, the cryptologists at Station HYPO in Hawaii were able to decipher JN-25 messages in a matter of hours. Over the next month, they learned that the Japanese Navy was planning an enormous invasion at a point known only as "AF." Based on a previously decrypted weather report, the cryptologists were sure the mysterious location was Midway, northwest of Hawaii.

Station HYPO leader Lieutenant Commander Joseph Rochefort believed his team was correct, but he had to prove their hypothesis to skeptics at OP-20-G. He had an unencrypted message sent via the Midway base to Pearl Harbor, saying the Midway desalination plant was broken. When the Japanese sent a message saying the desalination plant on AF was broken, it was clear his team had been right. They continued to decrypt messages that allowed the Navy to plan a strategy that caught the Japanese Navy by surprise and sunk most of its fleet.

Despite this, the former skeptics tried to take credit and blocked Rochefort from being promoted and honored — twice — according to the New York Times. He was finally awarded the Distinguished Service Medal in 1986, 44 years after the battle and nine years after his death.

The American codebreakers worked closely with the British

Although there was sometimes friction between the respective codebreaking departments of the U.S. Army and Navy, both branches were unusually keen to share information with a foreign power: Britain. Even before the U.S. entered the war, cryptologists from SIS and OP-20-G were communicating with their British intelligence counterparts, Government Code and Cipher School (GC&CS), now Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ).

In early 1941, two members of OP-20-G and two members of SIS (including Abraham Sinkov) braved the U-boats and Luftwaffe to visit the British codebreaking hub Bletchley Park. As GCHQ's historian Tony Comer told the BBC, America hadn't technically joined the war yet, and at first, the British were reluctant to share the hard-earned insights they had made into the Enigma code (with vital help from Polish intelligence services.) However, once the SIS gave them a copy of the machine they'd used to break the Japanese Purple code, the codebreakers agreed to open up about Enigma and the so-called bombe machines they were using to break it.

The collaboration escalated when America entered the war. It wasn't always plain sailing: OP-20-G was frustrated by Britain's failure to deliver a promised bombe machine, eventually making its own with what it saw as an improved design. But it laid the groundwork for the two nations' close ties today.

The codebreakers were sworn to secrecy

From their very first day of training, the codebreakers were told very clearly that revealing details of their work — even to their families — would be considered an act of treason punishable by death. This would be handed down to anyone, regardless of gender. According to the NSA, WAVES reporting to OP-20-G for the first time were told, "don't think that just because you are young ladies you will be treated any differently... if you ever tell, we will shoot you!" Even colleagues in different departments of OP-20-G were not allowed to discuss their work with people on different assignments.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Mundy recalled that some of the veterans she met while writing Code Girls were still unwilling to discuss their experiences. Instead, as Mundy told the AP, the women claimed that they had been secretaries — something the people they met found easy to believe, given women's limited employment opportunities and perceived intellectual inferiority. Even their future husbands — some of whom they outranked — didn't realize what they'd done for the war effort.