What It Was Really Like Taking Part In The Alamo

1836 was a crazy year. Mexico was in yet another battle over Texas, Mormonism was really taking off, and the revolver was suddenly a thing. But the Mexico thing was pretty significant since it eventually led to the Republic of Texas joining the U.S. of A. babayy! And would it really be America without big 'ol sassy Texas?

For some background on the whole Mexico/Texas situation: After Mexico gained control of the territory in 1821, it was still the real deal, the Wild West. Mexican leaders thought that their newly acquired, and very large, swath of land was in need of more people, aside from the Comanches and Apaches who were already living there.

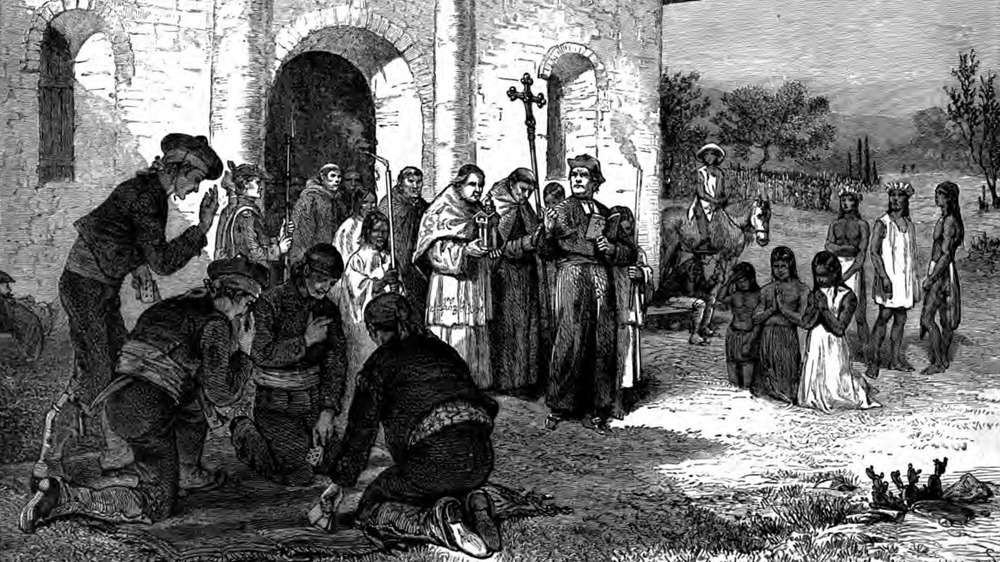

So, according to Smithsonian Magazine, they offered up cheap plots to Americans that came with a small request to convert to Catholicism and become unconditional patriots for Mexico during their stay. The new neighbors were pretty loose on those last two requests and were also coming by the thousands. Understandably, things quickly turned sour between the now-outnumbered Mexicans and proud Texans.

Smithsonian Mag tells how the first scuffle came in 1833, when a guy named Stephen Austin suggested Mexico and Texas break up and then told all the Texans to stop being friends with Mexico. Within two years, Texas had a bone to pick with Mexico. The ball was rolling toward Texas' independence, but it would take an old gem in San Antonio to get there.

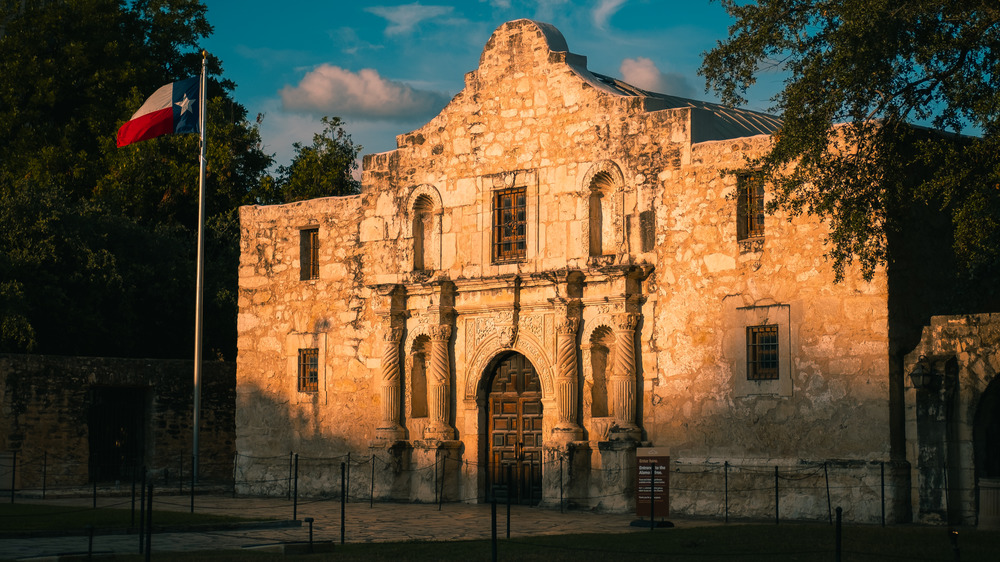

The Alamo was actually an old church

When the Battle of the Alamo took place in 1836, the walls of Mission San Antonio de Valero were 92 years old, according to the National Park Service. And while the structure had undergone plenty of modifications by the time Texas and Mexico had their squabble, J.C. Edmondson's The Alamo Story describes how it was mostly a marketplace equipped to combat the occasional raid of Comanche tribes.

But there was just something about this place that called to settlers to host their conflicts. Spain and Mexico also had a ruckus over the Alamo in 1810 while battling for territory. Spoiler alert: Mexico won that one. Luckily for the volunteer vigilantes of Texas, they had an engineer to spruce the place up before Santa Anna's guys came strolling into Bexar.

Per The Alamo Story, Green B. Jameson had impressive plans for the fort, with absolutely no time to execute them. He never made it to the glitzy moat and retreat stations but was able to install catwalks and windows along the walls so the men could at least have a half-protected spot to shoot from. These additions came right before Mexico's army showed up with a few thousand soldiers.

The commanders at the Alamo were mostly MIA

During the Battle of the Alamo, the Texan side was not only horrendously short on supplies from the jump, but leadership was also nonexistent when it was probably needed most, according to Texan Iliad by Stephen Hardin. Prior to the siege, Governor Henry Smith placed 26-year-old William Travis in command, but the guys who had already been following orders from the far more experienced James Bowie for the past few months weren't having it and voted Travis out of the position. Bowie decided, after a drunken celebration of his men's loyalty, that he didn't want any hard feelings and offered to share boss-ship with Travis.

According to the South Carolina Encyclopedia, William Travis jumped onboard with the resistance to Mexico's rule when he arrived in Texas in the early 1830s. When word spread that General Antonio López de Santa Anna was coming for the Alamo, Travis gathered 30 men to join him in Bexar. On March 6, the final day of the siege, Travis was supposedly one of the first shot while reloading his gun.

James Bowie (who did not, in fact, invent the Bowie knife) was a well-respected and experienced fighter, according to the Sons of DeWitt Colony of Texas. But a few days before things really started to heat up around the Alamo, he was laid up in bed, most likely with tuberculosis. Most historians believe that when the Mexican army flooded into the fort, he was killed, still lying in his cot.

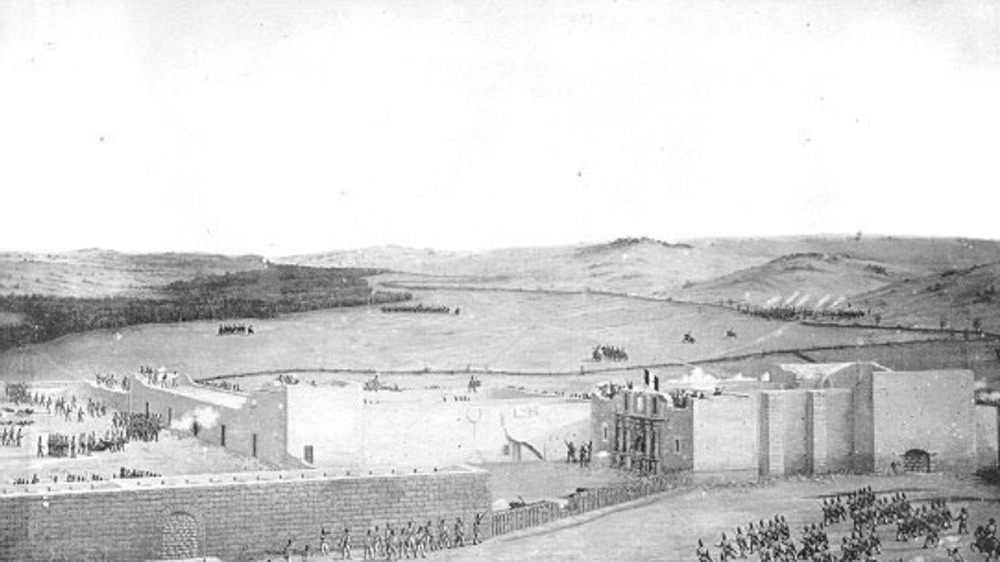

Santa Anna's army was pretty inexperienced

Let's just say that Mexico was lucky to have numbers as their defense against the Texans. In Texan Iliad, Stephen Hardin describes how Santa Anna brought around 5,000 men to the Alamo, many of whom were completely untrained and terrified. The country's toils to overcome Spain's control in Texas had left their forces in short supply. Most of the nation's men were unwilling to join due to embarrassingly low pay and little chance for reward.

By the time they arrived in Bexar in late February, the troops had traveled hundreds of miles through record snowfall with women and children, who were also gobbling up their rations, according to Walter Lord's A Time to Stand. But much of the combat before March 6 was with cannons, so at least they didn't have to show their inexperience early on.

Lord describes how they rarely shouldered and refused to actually aim their old, short-muzzled firearms due to the intense recoil, which would result in accidental killings of their brethren. On top of that, Stephen Hardin remarks on how their blunderbusses' range was limited compared to the Americans' rifles. But at the end of the day, or morning really, quantity over quality showed what was really necessary to take the Alamo.

The Texans were caught off guard ... twice

According to Albert Nofi's The Alamo and The Texas War For Independence, co-commander William Travis had suspected that Santa Anna was still days away when Mexican troops rolled into town on February 23. The evening prior, the Alamo defenders were throwing a birthday fiesta in George Washington's memory, as one about to wage territorial scuffles does. So no one in San Antonio knew that Mexico was less than 20 miles out and ready to rumble.

Nofi describes that by the early morning, word of the nearby troops had spread among the locals before it reached the garrison. People were packing up before daybreak, and Travis awoke to the patter of terrified townsfolk getting out of dodge. By late afternoon, San Antonio was fully occupied by Mexican cavalry.

Then, on the fateful morning of March 6, nearly two weeks after Mexico had the run of Bexar, the watchmen on the Alamo's walls had finally fallen asleep. As described in Texan Iliad, the three dozing guards had their throats cut in the dark, allowing Santa Anna's forces to quietly arrange into columns surrounding multiple sides of the Alamo.

According to J.C. Edmondson, once positions were set, Santa Anna's army placed their ladders against the 12-foot walls and erupted with "Viva Santa Anna! Viva the Republic!" waking the Alamo's defenders from a long-awaited slumber and immediately into battle.

Women and children were inside the Alamo

Enrique Esparza was one of the children hiding in the fortress during the attack. He was eight years old at the time, and he lost his father, Gregorio, who defended the Alamo. He told the San Antonio Express in 1902 (via PBS) about how the blackened room where he and his family were hiding was riddled with bullets for 15 minutes, missing all but one child, who was killed. After the battle, he said that Santa Anna gave his mother, along with the rest of the women, a blanket and $2 and sent them on their way.

According to PBS, Susanna Dickinson, the wife of a Texas soldier, recounted that once Santa Anna's army had made it inside the walls of the Alamo, men came flooding into where she was hiding trying to escape the Mexicans and were shot down on either side of her. Her husband had come in as the tragedy was quickly approaching its end to kiss her goodbye before going back into the massacre. She said that was the last time she saw him.

Juana Navarro Alsbury was another woman inside the Alamo who saw a lot more action than she bargained for. She said that toward the end of the battle, a soldier came barreling into the room where she was hiding and tried to use her as a human shield.

The Battle of the Alamo had a slow start

Although most of the action took place on March 6, the Battle of the Alamo technically lasted 13 days. Per Albert A. Nofi's The Alamo and the Texas War of Independence, Santa Anna raised a red flag to the Alamo, symbolizing that no mercy would be given, along with a bugle to parley. William Travis wasn't privy to the order of actions to take and prematurely fired a cannon in response. A sickly James Bowie chastised Travis for his lack of cultural awareness and sent out a letter to convene with the enemy.

The letter was delivered to Santa Anna's chief aide, Juan Nepomuceno Almonte, who wrote in his journal that he was told the Texans "wished that some honorable conditions should be proposed for a surrender." Santa Anna said their surrender would have to be unconditional and without any peaceful promises, according to Nofi. And so, Bowie and Travis responded to Santa Anna's terms by sending out a second cannon shot together.

For the following week, Almonte's journal recounts how Mexico and the Alamo threw cannonballs and shots back and forth daily, with Texas often reusing the cannonballs of Santa Anna's troops. In the night, Texans would come out and burn the structures the Mexican troops had moved into near the Alamo, along with the occasional sally (attack). Almonte wrote on March 4 that Santa Anna had decided it was time to assault the Alamo, and the plan commenced in the early morning two days later.

The Alamo's reinforcements flaked

William Travis had been calling for reinforcements weeks before Santa Anna rolled into San Antonio. But his last, desperate call for help went down in American history with a letter sent on February 24. It was addressed "To the People of Texas & All Americans in the World" to bring aid and supplies as Mexico's army was growing larger every day.

According Albert A. Nofi, the message made it to commander James Walker Fannin, who was 100 miles from San Antonio and had more than 300 men to contribute, two days later. They sent word to the Alamo and began marching to San Antonio on February 26. But after a mile in, they decided to turn back with the excuse of feeling underprepared to serve their fellow patriots, according to The Alamo Story, and Fannin failed to inform the Texan soldiers in the nearby town of Gonzales, who were sent to meet them. They continued to wait until an attack came from Mexican troops, according to Thomas Lindley's Alamo Traces: New Evidence and Conclusions.

Travis became extra antsy to receive Fannin's company on March 3, when Santa Anna's 3,100 reinforcements strutted into San Antonio, so he sent Davy Crockett and a few others to find Fannin and light a fire under his booty, which, of course, was to no avail, considering that he and most of the boys weren't coming. Lindley notes that Crockett found 20 of Fannin's men, who joined him as they snuck back to the Alamo.

Santa Anna's troops were fighting against their own countrymen

Many Mexicans rebelled against Santa Anna and joined the Alamo's forces, according to the Texas State Historical Association. Most seemed to have joined James Bowie's batch of renegades before the Alamo, rather than deserted any position with the Mexican army.

Santa Anna was aware he would be fighting some Tejanos (Mexican Texans) and surprisingly showed some class about it. He moved certain soldiers farther back in their stations so as to avoid troops meeting their kin in battle, according to The Alamo Sourcebook, 1836.

One incredible story that has lived past the Alamo is Francisco Esparza's, as detailed in Eyewitness to the Alamo. The Mexican soldier was granted special permission to retrieve his brother Gregorio's body for a proper burial. Francisco (the uncle of Enrique Esparza) didn't actually have to fight at the Alamo, but his allowance to have a memorial for his loved one is a hint toward the odd humanity hidden in the customs of war.

The Texans knew they were going to die

According to Enrique Esparza's account, Davy Crockett had met with Santa Anna multiple times before the siege on March 6, in hopes that he'd allow the Americans to surrender. But refusing to chance Santa Anna's already ominous conditions, Enrique said the rebels agreed they would together have to die fighting, no matter what.

Frank Thompson's The Alamo shows that in retrospect, the Alamo could have been prevented if James Bowie had followed his commander's orders to destroy it in the first place. It was evident that the old church was completely unfit for artillery-filled battle. But Bowie decided early on that he "would rather die in these ditches than give them up to the enemy."

William Travis' famous letter from the beginning of the 13-day campaign was also bleakly accurate to the Texans' dark future: "If this call is neglected, I am determined to sustain myself as long as possible & die like a soldier who never forgets what is due to his own honor & that of his country VICTORY OR DEATH." Per Thompson's work, the greatest Alamo legend has it that Travis drew a line in the sand and asked whoever was ready to die for the future of Texas to cross over it. All but one came to Travis' side, and that man supposedly wandered through the wilderness until making it home to tell this tale.

Weaponry was highly improvised

The Alamo was short on supplies from the jump, considering that it really wasn't a fort by reasonable standards to begin with. They had 19 hand-me-down cannons from Mexico's recent ownership, some of which were hand-me-downs from Spain's stint in the Alamo, according to the Association of American Universities.

And with little ammunition to supply them, the Texans became MacGyvers with better mutton chops. The Alamo Story says that after they weren't able to reuse Santa Anna's cannonballs anymore, they went on launching anything usable, from door hinges and nails to busted up horseshoes, out of their 16-pound rainmakers.

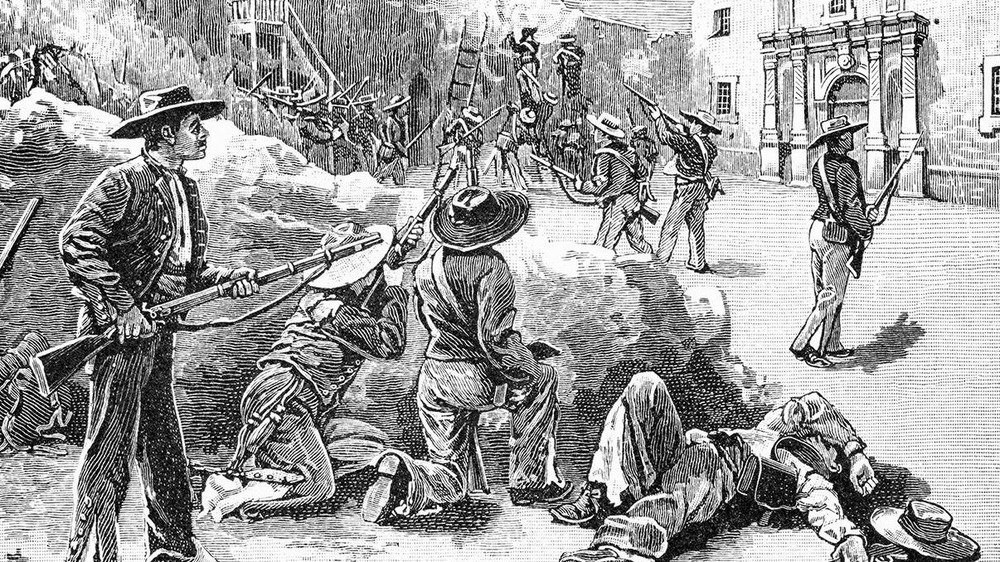

Texan Iliad notes that in the last moments inside the chapel, it was hand-to-hand combat, since the defenders didn't have enough time to reload those old muskets as the enemy charged. They clubbed one another with muskets and pistols and stabbed away with bayonets and Bowie knives — of course.

The thick of it was over in less than an hour

Per Juan Nepomuceno Almonte's journal, the final, infamous showdown began on March 6 at around 5:30 in the morning and was over by 6 a.m. Stephen Hardin's Texan Iliad details how the stout army of 188 Texans impressively held off the troops for the first advance, helped by the fact that the Mexican troops were arranged in easy-to-shoot clusters. Also, Santa Anna's guys kept accidentally shooting one another in the darkness during the commotion.

At first, the Texans were able to hold off the troops scaling the walls, but Mexico's numbers quickly overwhelmed them, according to Hardin. Once the troops were able to breach the already damaged north wall of the Alamo, they flooded into the fort, killing every defender in sight. The total number of casualties is still in debate, but J.C. Edmondson states that the majority of the Texans' bodies were burned, while the Mexican corpses that couldn't fit in the graves were tossed in the river. The women and children were spared and sent on their way to spread the word about Santa Anna's win.

According to the Texas State Historical Association, one Texan survivor was William Travis' slave, Joe. A Mexican captain saved him after he was shot and stabbed, as Mexico's condemnation of slavery was a contributing factor to tension with the Texans. Joe was sent back to Travis' estate but was sprung by an unknown man from Mexico on April 21.

Davy Crockett's contribution at the Alamo became instant legend

Davy Crockett was a notable figure even in his time, according to J.C. Edmondson. Firsthand accounts, including from William Travis, say the humble Tennessee fighter rallied the men, conversed with the families, and only got into trouble that was worthwhile. The 49-year-old congressman was a man of the people, and thus, a man for Texas.

Young Enrique Esparza found the Southern stranger instantly memorable: "He was a tall, slim man, with black whiskers. He was always at the head. The Mexicans called him Don Benito." He said he also remembered seeing Crockett's body surrounded by dead Mexican soldiers as he was escorted out of the Alamo. But that's not the only supposed firsthand account of how Davy went out.

According to a 1998 Miami Herald article (via Latin American Studies), some eyewitnesses said he died like the others inside the Alamo's walls. The most controversial is the claim from Santa Anna's Lieutenant Colonel Jose Enrique de la Peña, who said Crockett was executed after the battle. Peña's highly contested diary sold for $350,000 in 1998.