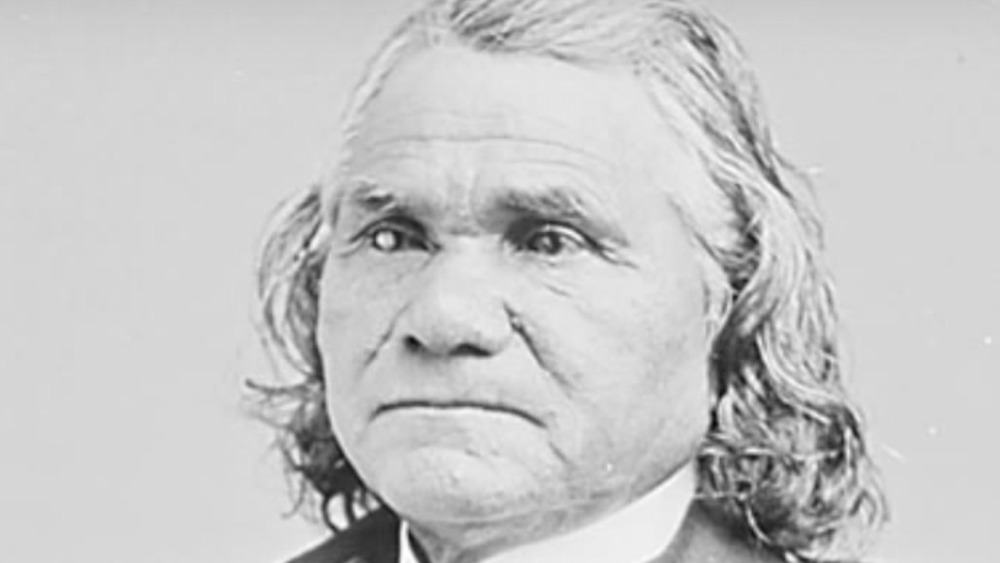

The Surprising True Story Of The Native American Confederate General

For nearly his entire life, Stand Watie lived in two competing worlds. Born in 1806 in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains in northwest Georgia, his parents, David Uwatie, a Cherokee, and Susan Reese, of European and Cherokee descent, gave him the name Degataga, which means "Stand Firm" in the Cherokee language, according to the Napa Valley Register. Like many children in planter class families, Watie had been baptized, received a Western-style education from Christian missionaries, and grew up bilingual. Anglo-Americans deemed Cherokees one of the "Five Civilized Tribes," because they had embraced those Western conventions, and some had a willingness to use African slavery to compete in agricultural markets.

As a young adult leader in a powerful minority Cherokee faction, known as the Treaty Party, Stand Watie signed the Treaty of New Echota in 1835 with the U.S. government. It was an agreement that would become the legal basis for the forcible removal of the Cherokee people from Georgia, known as the Trail of Tears. For his part, according to the American Battlefield Trust, Watie believed that removal was inevitable, arguing it would be better to secure Cherokee rights in the form of a treaty and to relocate to Indian Territory, primarily in Oklahoma. In Indian Territory, many of those who signed the treaty, including some in Watie's family, were assassinated for giving up the tribal lands. Stand Watie was somehow spared.

Stand Watie joined the Confederacy in the Civil War

In 1861, as the Civil War broke out, Stand Watie joined the Confederacy, because, in his view, the federal government was the enemy of the Cherokee people. He organized the first Indian regiment of the Confederate States Army, the Cherokee Mounted Rifles, who participated in more than two dozen major engagements. Because they were not well equipped, according to HistoryNet, the regiment relied on guerrilla tactics for their notable victories, including capturing a Union battery, seizing the Union steamboat J.R. Williams, and snatching $1.5 million in supplies from a Federal wagon supply train.

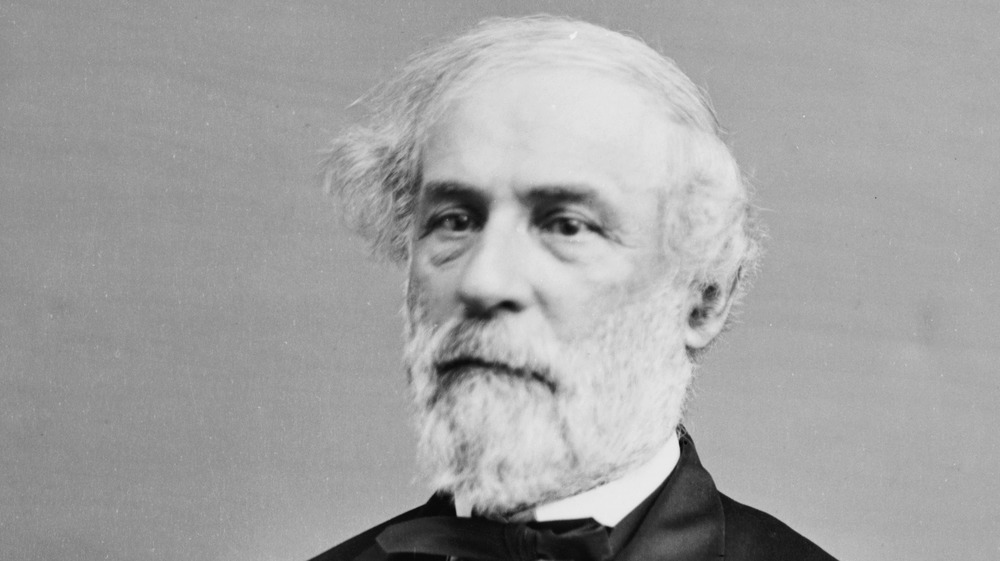

Watie was in such support of the Confederacy that in 1863, when a majority of Cherokees rejected the alliance with the Confederate Army, Watie redoubled his efforts. The Confederacy rewarded him with a promotion to brigadier general. And even after Robert E. Lee (pictured above) surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House in Virginia on April 9, 1865, Watie became the last Confederate general to surrender – 75 days later, as the Oklahoma Historical Society notes.

Watie largely retreated from public life, but not before he could anger the majority of Cherokee people one more time. The next year, he traveled to Washington D.C. for negotiations on the Cherokee Reconstruction Treaty of 1866, which, according to History.com, took away massive swaths of land from tribe members as a condition for reinstatement in the Union. On September 9, 1871, Watie died on his Honey Creek plantation.