What It Was Really Like To Take Part In A Duel

If you think of a duel of honor today you most likely conjure up an anachronism of the past — an illogical, violent affair that is best understood through Bugs Bunny cartoons. Who in their right mind would stand and freely shoot at somebody at 20 paces? However, to a good many people of earlier times, the duel was a serious thing that served an important function. To them, dueling was a ritualistic defense of one's validity as an individual. In a word, it was about honor. At its peak in the 18th and 19th centuries, dueling was at once condemned by moral and governmental authorities as a barbaric practice but at the same time broadly accepted throughout elite society in the Western world.

The questions then are, what drove men (and some women) to settle conflicts with pistols or swords? The answers are surprising, and reveal that dueling had its place as a less violent option for settling scores in a violent society. The answer also has deep roots, going back to antiquity. Let's see what it was really like to take part in a duel.

When trial by combat seemed a sensible way to decide court cases

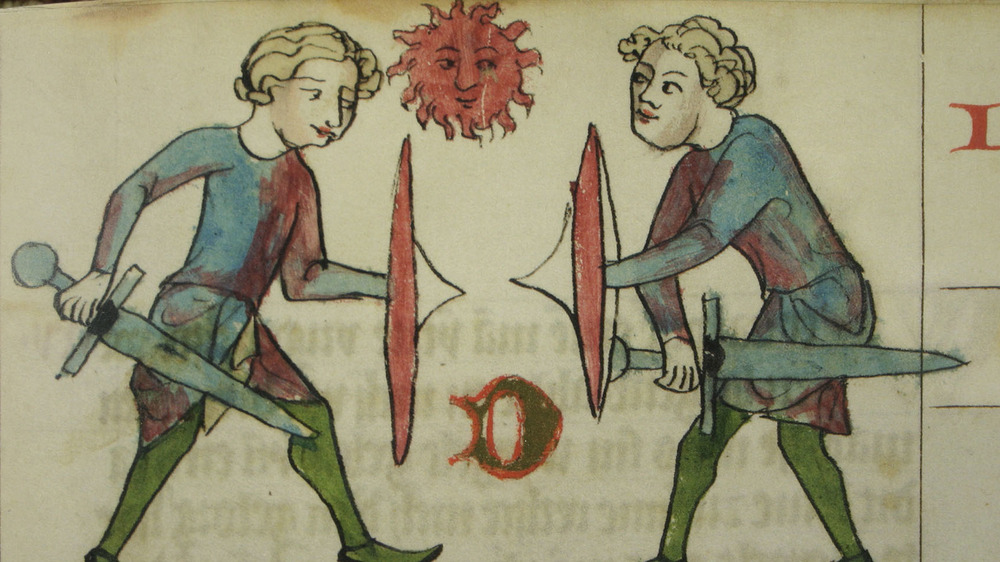

The earliest reports on dueling come from the Romans. According to Britannica, both Julius Caesar and the historian Tacitus reported that the ancient Germans often settled differences through single combat. After the Western Roman Empire was invaded by Germanic tribes, this practice became widely adopted, so that by the early Middle Ages, you have the appearance of the judicial duel or trial by combat.

According to The Last Duel, this form of justice involved two persons of any social class or sex who fought one another over civil disputes. Whoever won the combat won legally since it was assumed that God would select the victor. If a person could not fight for whatever reason, a champion was selected.

This form of justice slowly lost favor throughout the period. Popes denounced the practice as being immoral, and kings did not like it, since it usurped their judicial authority. Over time, the judicial duels were removed from civil proceedings and relegated to noble males in criminal cases. Then, even after it was abandoned from use in court, people still practiced it privately. Steven C. Hughes in the Journal of Medieval Military History explains that by the time of the Renaissance, the modern conception of a duel of honor was firmly established.

The first duels of honor were encouraged by the printing press

The journal I Tatti explains that the modern form of dueling evolved in Italy during the Renaissance. Part of the reason why it developed at this place and time was that modern nation states were developing and the rights of lesser nobility were being weakened. The duel was a way in which an aristocrat could express power. Dueling was also encouraged through the invention of the printing press which in the 16th century published numerous treatises on defending one's honor. The duel became a civilized form of violence.

From Italy, dueling spread rapidly among European aristocracy, first arriving in France. National Geographic reports that during the reign of Henry IV (1589-1610) about 10,000 duels occurred in the kingdom resulting in up to 5,000 deaths. France became a mecca of dueling by the 17th and 18th centuries despite efforts by authorities to curb and ban it. Even the philosopher Rene Descartes took part in a duel over the honor of a lady.

At this stage, there were informal rules for dueling usually involving clothing type and weapons. Armor was taboo and duelists usually wore a shirt exposing their chest. Weapons were typically swords although as time went on pistols became increasingly more common. It is notable that a good third of duels never took place since an arrangement was negotiated before the actual fight.

Dueling crosses the Atlantic

As Europeans began to explore and establish colonies around the globe, dueling practices followed. According to a 19th century article from Frank Leslie's Popular Magazine, the first recorded duel in the American colonies took place on June 18, 1621 in Plymouth. This was just a year after the Pilgrims made their famous landing. Uniquely, this very first American duel was fought not between aristocrats but between servants Edward Doty and Edward Lester. Maybe this presaged the growth of democracy in America. The pair battled with swords and daggers. Both men, although wounded, survived the fight. However, the outraged leaders of the Plymouth colony punished them by binding their heads and feet together.

Still, the practice of dueling spread through the colonies. As with dueling's earlier history, it was not universally accepted. In a letter, Benjamin Franklin called dueling a "murderous practice" and while he excused earlier judicial combat practices, he viewed fighting for the sake of honor as pointless. He wrote that duels "...decide nothing. A man says something which another tells him is a Lie. They fight, but whichever is killed, the point in question remains unsettled." George Washington was also against dueling according to PBS.

Rules of Honor

Dueling was regulated by formal rules which varied over time and place. The most well-known rule book is the Code Duello. Its rules were, as reported by the New Yorker, written out by Irish duelists. This was the code largely used in the United States during the time of the famous duel between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr in 1804.

Even though the Code Duello is a brief document with only 26 rules, they are complex. The code notes how certain offenses which cause a duel are greater than others. Rule five explains how serious an offense striking a "gentleman" was: "As a blow is strictly prohibited under any circumstances among gentlemen, no verbal apology can be received for such an insult. The alternatives, therefore, are: The offender handing a cane to the injured party to be used on his back, at the same time begging pardon, firing until one or both are disabled; or exchanging three shots and then begging pardon without the proffer of the cane."

If swords are to be used instead of pistols, the code rules that the duelist must engage until "...one is well blooded, disabled, or disarmed, or until, after receiving a wound and blood being drawn, the aggressor begs pardon." Also of note from the code is that it is expected that any gentleman engaging in a duel must be of deadly earnest. Shooting blanks or shooting in the air was viewed as "children's play" and was prohibited.

Duelists used all sorts of weapons, including billiard balls

The main weapons used by duelists were swords and pistols. National Geographic reports that from the time of the Renaissance, rapiers were preferred. These elegant weapons, which were thinner and longer than earlier swords, did not mutilate a person like a two-handed claymore, but because of their piercing ability could be far more lethal.

The models of pistols changed over time. According to the Smithsonian, in the early 19th century, the weapon of choice was a large caliber, flintlock pistol such as Simeon North's model 1817. One of the reasons why most elite males owned a pair of these pistols was because it was smoothbore. This means that the inside of the gun barrel is smooth instead of having grooves as a rifle would. The result of this was that a shot from a smoothbore pistol did not have spin which meant that it would often fall off course, being inaccurate. Inaccuracy was also increased because, according to the Historical Journal, dueling pistols lacked sights. The inaccuracy led to fewer deaths. This was done purposefully.

Weapons were not just limited to swords and pistols. According to Giacomo Casanova's The Duel, in September 1843, two young men in Maisonfort, France argued over a game of billiards. They decided to settle their differences with a duel, using billiard balls. One of the duelists was killed almost instantly with a well-aimed throw at his forehead. His opponent was convicted of manslaughter.

How do you pick a duel?

Let's say you wanted to go back in time and for whatever reason would like to participate in a duel. What would you do? You'd want to make a derogatory remark to a man of the upper class, perhaps even calling him a scurrilous cur. If a lower class person insulted an upper class man, he was most likely, according to the Library of Congress, just beaten out of hand. So if somebody challenged you to a duel, they are tacitly admitting that you are a gentleman too and will play by the rules.

There were other causes for dueling, too. A 19th century treatise on the subject recalled how a Neapolitan fought 14 duels to prove that Dante was a better poet than Ariosto. It was evidently just an excuse, since on his deathbed the duelist admitted to his confessor he had read neither. In the early United States, duels were often fought due to political rivalries such as the Burr-Hamilton duel according to Britannica. Mental Floss reports that President Andrew Jackson participated in over 100 duels in his lifetime. Many of these duels were over the reputation of his wife Rachel who had divorced an abusive husband and remarried Jackson. The question was whether Rachel's divorce had been finalized by the time she married Andrew.

Duels are not the same thing as a gunfight

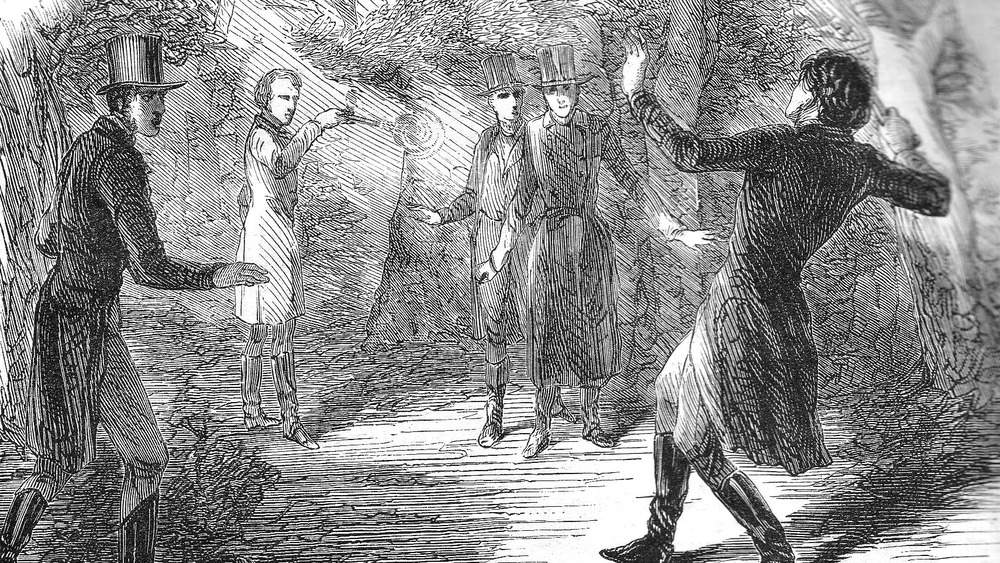

If it is not clear already, duels are not the same thing as a Wild West gunfight. These were deliberate affairs following clear protocols. The New Yorker points out that the object of entering a duel was not to murder your opponent. The point of the whole thing was to defend one's honor. In fact, it really didn't matter if you won or lost. What mattered was following the code. Usually it took some time between the time of the offense and the duel itself, especially if the duel called for pistols. During that time the duelists often negotiated, looking for a peaceful way out of the confrontation where both could save face.

Take for example, the duel between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr. Aaron Burr had demanded an explanation for overhearing "I could detail to you a still more despicable opinion, which General Hamilton has expressed of Mr. Burr." Hamilton disputed Burr's take on this in a letter dated June 20, 1804, but the two men did not meet to duel until July 11. While no resolution was made and the duel did take place, it certainly was not an instance of Aaron Burr chasing down Hamilton in the street and gunning him down.

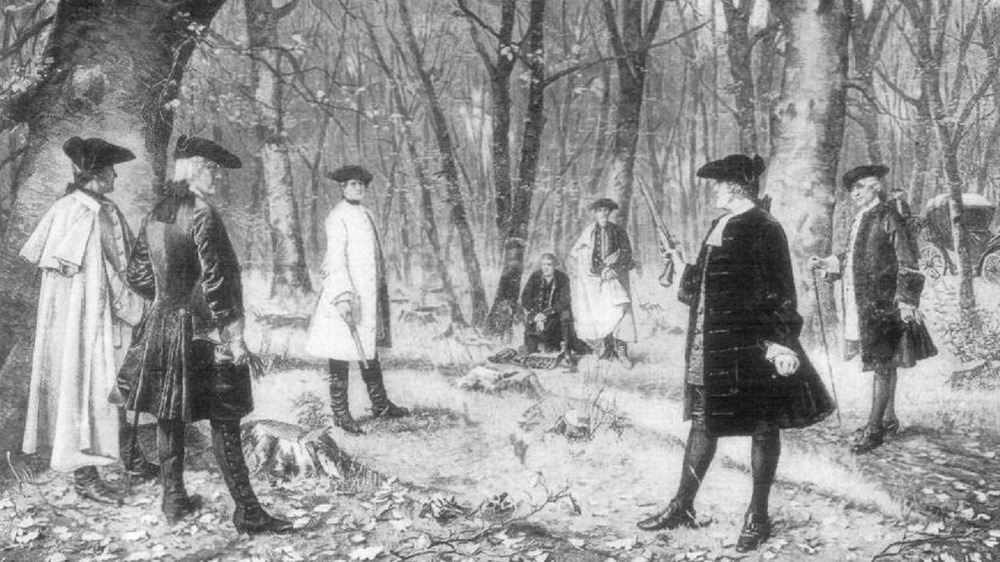

Duelists always had back ups

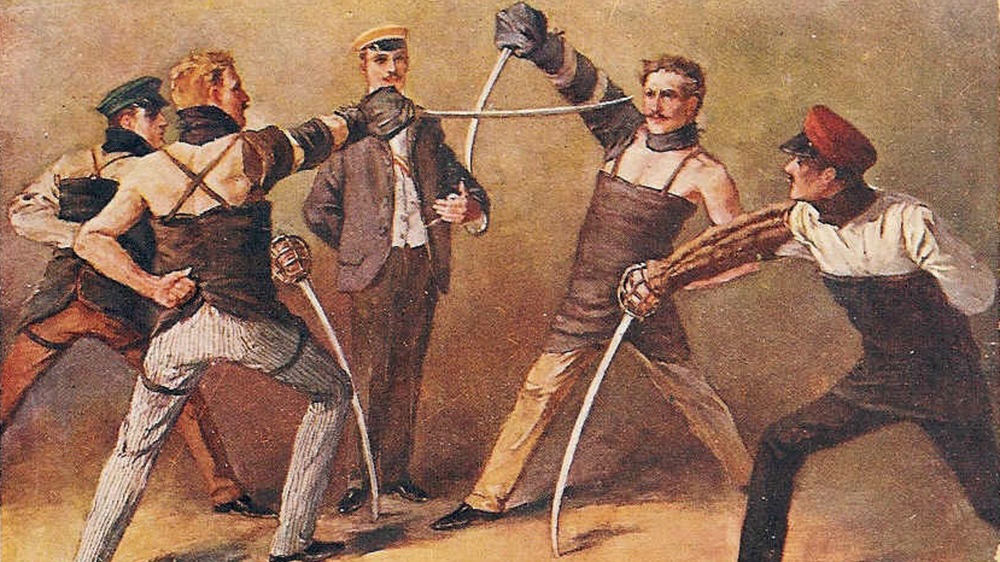

If you took part in a duel, you didn't have to go it alone. In fact, it was expected that you wouldn't. Duelists relied on their "seconds." Seconds were friends who essentially had your back during the duel. Early in dueling history they had a bellicose role. As described by the Historical Journal, seconds often fought too turning a one-on-one conflict into a group melee. In fact, there could be thirds or more. The Historical Journal quotes a source from the 1680s as writing, "the mode nowadays, is for all the seconds to draw at once with the principal, and among them the engagement is as vigorous as if each were the very person that first gave the affront." The journal then gives an example of a 1668 duel involving the Duke of Buckingham and Lord Shrewsbury which turned into a three-on-three sword fight resulting in two dead.

If you were to take part in a duel in the late 18th or 19th centuries, you would find that the role of your second had evolved. HowStuffWorks describes the second as a friend who came along to help you, ensure that your weapon was properly loaded, and that the rules were being followed. What is more, a proper second would try to negotiate some sort of peace on your behalf so that violence could be avoided all together. Deaths by dueling diminished after the role of the second changed.

Twenty paces at dawn

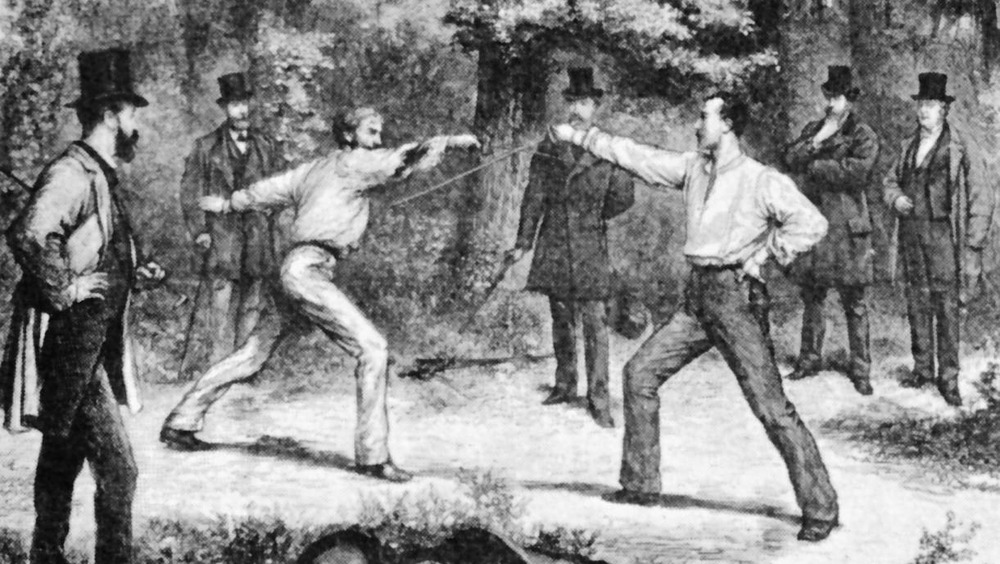

It seems counterintuitive that after pistols became the preferred dueling weapon, deaths would lessen. However, aside from purposely making dueling pistols so that they were not accurate, the Historical Journal points out that duels by pistols were much more deliberate than by sword. There were longer delays between when an offense occurred and the actual duel because people typically did not carry dueling pistols with them as opposed to swords which, especially early on, were more likely to be on hand. Dueling by pistols was also different than using swords since when you duel by sword it is a contest of skill. Dueling by pistol was much more random and prone to misses. In fact, it was considered extremely bad etiquette if you took deliberate aim and fired.

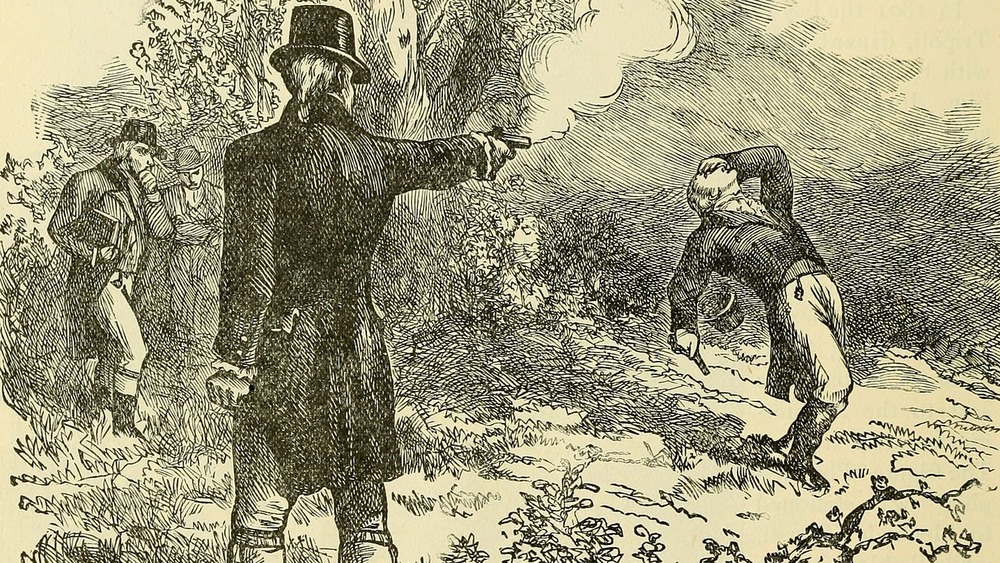

The general procedure of a pistol duel, as described by Masculinity, Crime, and Self-Defense in Victorian Literature explains this randomness. The seconds would arrange for the meeting, typically at dawn and in a location where dueling was still legal. The duelist would then stand back-to-back and take an agreed number of paces before turning. Then a second or some other moderator dropped a handkerchief before firing started. Sometimes the duelists would shoot simultaneously, sometimes they would take turns. Shots were then exchanged until satisfaction was reached or one of the duelists was seriously wounded. There was no loss of face if wounded in a duel. In fact, whether unscathed or killed, honor had been restored.

There was no chickening out of a duel

If you found yourself challenged to a duel you may think that it was crazy. You may even want to back out. If you did you would find yourself a social pariah. As the Journal of Legal Studies details, depending on where you were, such as the antebellum South, you would find that most of the social elite accepted dueling as a social norm. While there were no legal ramifications for chickening out of a challenge, you would find yourself very suddenly on the outside of society.

While it is hard to believe, even Abraham Lincoln found himself involved in a duel. As told by the American Battlefield Trust, James Shields challenged Lincoln to a duel in 1842 for libel. Lincoln as the challenged had the right to choose weapons so he opted for cavalry broadswords with the idea that it was safer than pistols. When the two met, Lincoln and Shields faced off with a plank between them that neither could cross. Lincoln, who was 6'4" to Shields's 5'9" easily reached over and hacked off a branch. It became obvious that Lincoln's superior reach would be fatal to Shields. A truce was called and Shields would later serve as one of his generals during the Civil War. When asked later if it was true if Lincoln took part in a duel, the president said, "I do not deny it, but if you desire my friendship, you will never mention it again."

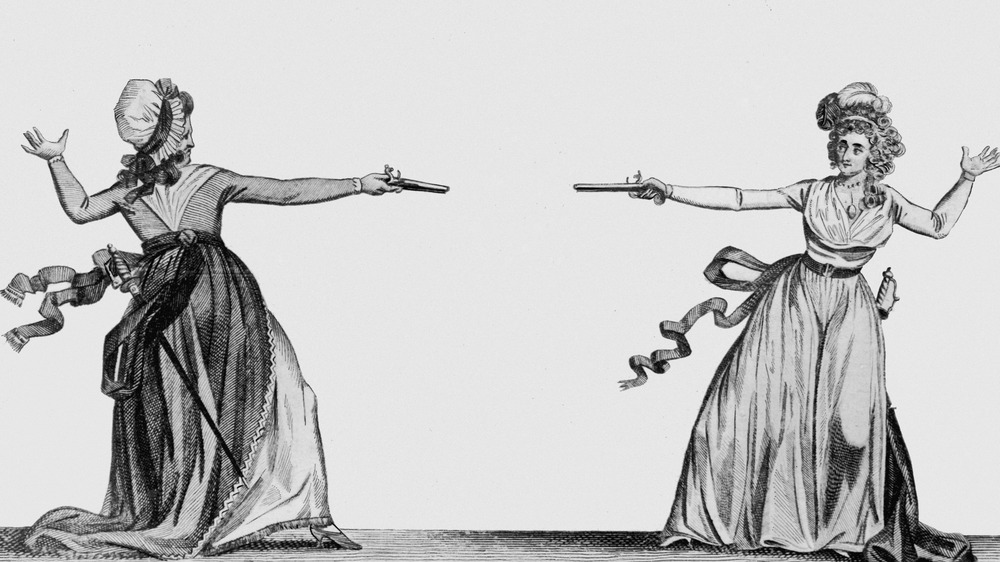

Dueling was not just a men's club

While primarily practiced by males, nothing prevented women from dueling. In fact, there are several notable duels involving women. Mental Floss relates several prominent cases, including a 1552 duel between the Neapolitan ladies Isabella de Carazzi and Diambra de Pottinella. The pair were apparently good friends until they discovered that a gentleman named Fabio de Zeresola was having relations with both of them. Both ladies claimed that Fabio loved them more and soon enough, friendship turned to feud and Diambra challenged Isabella to a duel. The two met on horseback and fought each other using lances, maces, and swords. Diambra ended up winning, forcing Isabella to give up her claim to Fabio.

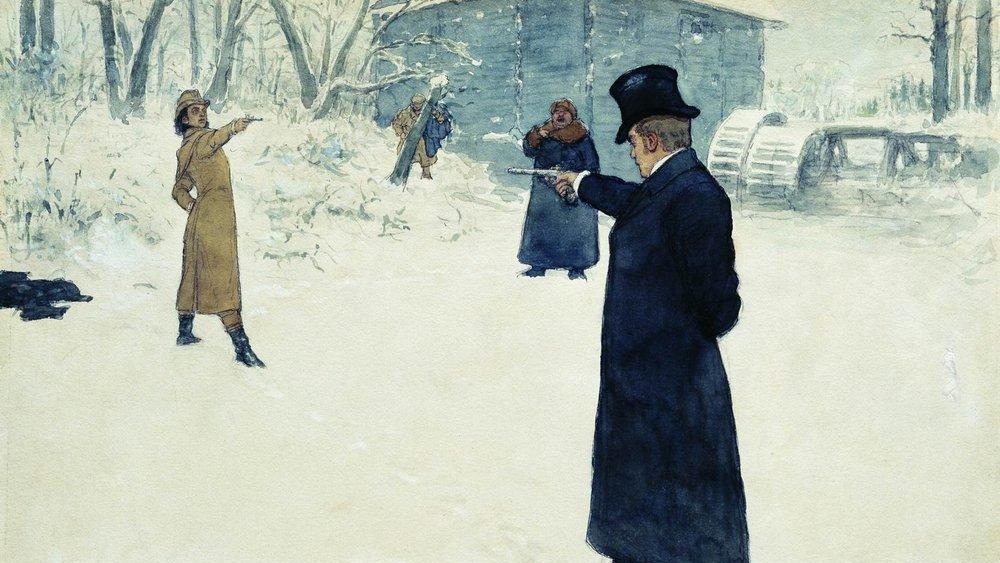

Another, more tragic case as described by the History Collection occurred in 1829 in Russia when two neighbors, Olga Zavarova and Ekaterina Polesova decided that the only way they could settle their differences was in a duel. With their daughters watching and the families' governesses acting as seconds, they fought with sabers under a birch grove. With both their daughters as witness, both ladies were killed. The tragedy extended to 1834 when their daughters, Alexandra Zararova and Anna Polesova, met at the same grove and repeated the duel with sabers. Alexandra killed Anna, thus ending the feud in blood.

Dueling dies

From its beginning, there were always critics of dueling but as the 19th century progressed opposition coalesced around it. According to scholar Wade Ellett, the last recorded duel in England was in 1852. According to PBS, dueling fell out of favor slowly.

The last notable recorded duel in the United States was between Senator David Broderick and Davis Terry in 1859. This duel was political in nature over the issue of slavery. As the National Park Service reports, Broderick was adamantly against the expansion of slavery while Terry, a California Supreme Court Justice, was for it. Despite them being friends, Terry accused Broderick of undermining him in an election he lost. After harsh words, Broderick challenged Terry to a duel. Terry ended up killing Broderick with a pistol shot. Before dying, Broderick said, "They killed me because I am opposed to the extension of slavery and a corrupt administration."

After the Civil War, dueling tumbled headlong into decline. States started to enforce anti-dueling laws. By the time of the early twentieth century, dueling was an anachronism. Yet from time to time, dueling still made a rare appearance. The last known duel occurred in 1967 between French politicians Gaston Defferre and Rene Ribière in Neuilly-sur-Seine. The two met right before Ribière's wedding and Defferre said that he would, "spoil his wedding night very considerably." Defferre did land a couple of light blows before the fight was halted. Videos of the proceedings have even been unearthed.