The Former Klansman Who Joined The Supreme Court

If asked to name history's most contradictory Klansman, one might intuitively choose the Chappelle's Show character, Clayton Bigsby, the sightless "white" supremacist who redefined colorblindness in that he literally couldn't see that he was actually black. But in a twist nobody saw coming, the most inconsistent Klansman ever might have been a white guy from Alabama, namely Supreme Court Justice Hugo L. Black.

Born in 1886, Black was the eighth and youngest child of an ex-Confederate soldier, per Constitution Daily. He was reared in a backwater and referred to himself as "just a Clay County hillbilly," according to biographer Roger K. Newman (via Constitutional Commentary). But he was a brilliant hillbilly, a largely self-taught attorney who attended law school without an undergraduate education and still graduated with honors (via the Encyclopedia of Alabama).

After Black joined the Supreme Court in 1937, the public learned that he had previously joined the Klan. Scandal ensued as it seemed Justice was blindsided on a Clayton Bigsby-like scale. However, reality is rarely black-and-white. Across his legal career, Black fought racism in the criminal justice system, supported school integration, and penned historic opinions championing civil liberties. But a few cases could leave you eager to throw the book at him for sounding more like a white supremacist than a court supremacist.

We can't fully do justice to Hugo Black's vast legacy or complexity. But we'll try to present compelling facts and let a jury of our readers judge our execution.

To Hell and Black

Hugo Black launched his first law office in Ashland, Alabama after acing law school in 1906, per Oyez. It struggled to take off before going up in flames during a 1907 town square fire (via the Encyclopedia of Alabama). Black rose from the ashes in Birmingham, where he gained acclaim in the courtroom and took a stand against convict leasing. For context, convict leasing entailed leasing predominantly black inmates to private companies to do excruciating work like mining. Mistreated and malnourished, many effectively suffered a slow-motion execution. Author Shane Bauer called it "prison slavery," noting the constitutional loophole that allowed slavery to persist after the Civil War "as a punishment for a crime" (via Slate).

In Black's first Birmingham trial, he successfully represented a black ex-convict named Willie Morton in a lawsuit. As Martindale detailed, a steel company kept Morton working in a coal mine 22 days past his sentence. The presiding judge later became the city's safety commissioner and tapped Black for a police court judgeship in 1911. Black's swift efficiency and amusing bench-side manner prompted a reporter to dub the judge "Hugo-to-Hell."

Police court may have exposed Hugo to hellish abuses of police power, according to Constitution Daily. Officers brutalized suspects and kept them "incommunicado," explained an expert in the PBS series, The Supreme Court (via Thirteen). Defendants could find themselves defenseless because they weren't guaranteed an attorney. Black felt the Bill of Rights should prevent those wrongs.

A farewell to harms

In 1914, Hugo Black became the newly elected prosecutor of Jefferson County, Alabama. Though he no longer held a police court gavel, he dropped the hammer on egregious policing. Writing for Catholic Law University Review, Daniel Berman observed that Black wasted no time trying to put a stop to "the law's delay." Officers were exploiting a fee scheme that paid jailers daily for each detainee, needlessly prolonging wait times before trials. As detailed by The New York Times, cops largely targeted impoverished black people.

While seeking office, Hugo argued that "the people were tired of having hundreds of Negroes arrested for shooting craps on payday and crowding the jails with these petty offenders." In keeping with his promise, he quickly freed 500 inmates. He also uncovered that officers in Bessemer, Alabama devised a nasty tactic to coerce confessions. They beat people bloody with a buckle attached to a leather strap, and black suspects suffered the bulk of the abuse.

The long arm of the law might have been out of Black's legal reach in Bessemer. So he gave his investigative findings to a grand jury, which agreed with his assessment that the cops' conduct was "dishonorable, tyrannical, and despotic." In 1917, Black resigned to serve in WWI. When he returned, he went back to being a private attorney and met future wife Josephine Foster.

The Ku Klux Klergyman

As a trial lawyer, Hugo Black was not only a legal eagle but a shark who shed crocodile tears. Per Thirteen, an expert featured in PBS's The Supreme Court said Black cried on command. But his tears didn't flow freely or even cheaply. He was known to say, "Hugo Black doesn't cry for less than $25,000." So the devious theatrics he used when defending Reverend Edwin Stephenson must have cost a fortune.

The Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics and Public Policy explained that Stephenson was a Methodist minister and Ku Klux Klansman who detested Catholics. In 1921, his daughter Ruth, who converted to Catholicism, married a Puerto Rican named Pedro Gussman. Afterward, Stephenson fatally shot Father James Coyle, the priest who conducted the ceremony. Charged with second-degree murder, the minister pleaded self-defense, and Black tacked on a plea of temporary insanity. Stephenson testified that he thought Gussman was black. So he confronted Coyle, declaring, "You have ruined my home. That man is a n***er." He claimed the priest struck him and seemingly reached for a gun (that was never evidenced to exist), forcing Stephenson's hand.

The jury was teeming with Klansmen. The police chief was on Team Klansman. The KKK funded Stephenson's defense. Catering to his audience, Black darkened the courtroom and had illuminated Gussman with floodlights to emphasize his skin tone. He claimed Gussman had curly hair. He questioned witnesses about practicing Catholicism. Stephenson was acquitted.

Hugo BlackkKlansman

Hugo Black spent part of the early 1920s guarding society's underdogs regardless of race. Biographer Steve Suitts told NPR that Black "represented ... the first interracial movement since Reconstruction," a union of striking miners who had been met with state-authorized violence on behalf of industrialists. He also sought to eradicate convict leasing in Alabama (via the Encyclopedia of Alabama). Yet as American Heritage described, in 1923, the legal egalitarian was sworn into Birmingham's Robert E. Lee Klan No. 1.

Black gave speeches at roughly 150 Klan gatherings and participated in marches, according to Constitution Daily. He resigned in 1925, but what made him join? In a New York Times interview published after Black's death, he offered a look under the hood: "I was trying a lot of cases against corporations, jury cases, and I found out that all the corporation lawyers were in the Klan. A lot of jurors were, too." Insisting the KKK was less hateful back then, he called it "a fraternal organization" comprised primarily of "the cream of Birmingham's middle class."

Notably, Black's frat, Kappa Kappa Kappa, hated alcohol. Citing Suitts' work, Alabama Public Radio said Black's hard-drinking father died of liver cirrhosis. His favorite brother died in an alcohol-fueled accident, according to history professor David Chalmers. Doggedly pro-Prohibition, he hounded bootleggers as a prosecutor, per the Encyclopedia of Alabama. Meanwhile, the KKK's influence flourished during the temperance movement as it violently persecuted Catholic immigrants under the pretext of enforcing Prohibition (via History).

Hu-goes to Congress

Running as a prohibitionist, anti-industrialist Democrat, Hugo Black clinched a U.S. Senate seat in 1926, per the Encyclopedia of Alabama. He had the blessing of Baptist voters, and the Klan rallied around him politically. Quoting legal scholar and biographer Roger Newman, Gary Stein wrote that the Grand Dragon of Alabama was Black's friend and de facto campaign manager (via Constitutional Commentary). Though Black would later tell The New York Times that the KKK he joined "wasn't anti‐Catholic, anti-Jewish or anti‐Negro," he spewed anti-Catholic rhetoric at Klan gatherings while campaigning, according to History. As reported by the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, the Alabama senator co-led a filibuster against the Costigan-Wagner anti-lynching bill, calling it unconstitutional. Black thought such legislation would upset Southern whites, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica.

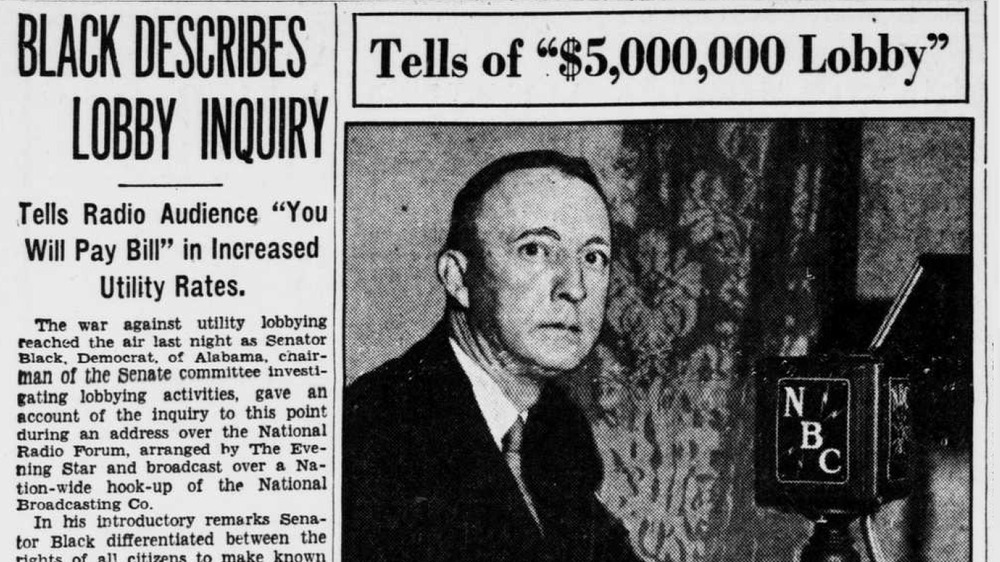

Black's Senate tenure was defined by far more than his Klan-stituency. After being reelected in 1932, he mounted a history-making investigation of utility company lobbyists. As the Senate Historical Office described, Congress had been bombarded with 15,000 telegrams opposing legislation aimed at dismantling "power trusts." It seemed fishy to Black, who put on his prosecutor hat and grilled witnesses. It turned out a utility company hired messengers to collect telegram signatures (via AL), prompting Congress to adopt its first-ever lobbyist registration system.

Black's Klan-destine past comes to light

An ardent FDR loyalist, Alabama Senator Hugo Black crafted the precursor to one of the New Deal's brightest highlights. The Encyclopedia Britannica cited as one of the reasons Roosevelt chose him for the Supreme Court. According to the Encyclopedia of Alabama, Black advocated capping the workweek at 30 hours and implementing a minimum wage, introducing a bill in 1932 that evolved into the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938.

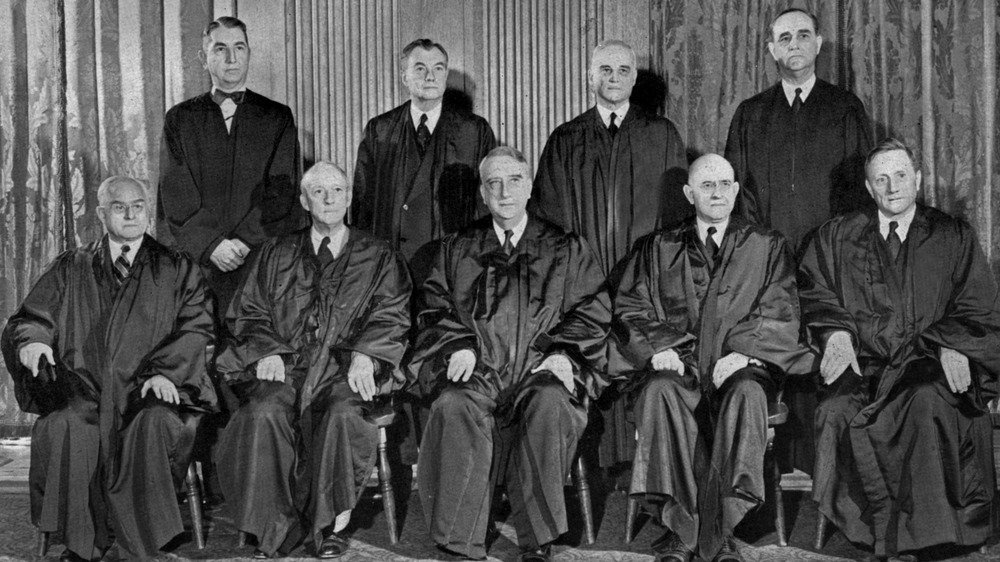

Black also supported FDR's plan to pack the Supreme Court. While that failed, Black joined the nine-justice lineup in 1937. The University of Chicago Law Review wrote that opponents to his nomination complained but couldn't prove that he had Klan connections. A common taunt in Washington was that "Hugo won't have to buy a new robe; he can dye his white one black." One lawmaker decried his appointment as "the grossest insult to the Supreme Court and the American people."

Weeks after Black's confirmation, his Klan ties were confirmed in a six-part exposé by journalist Ray Sprigle that earned a Pulitzer Prize. Sprigle believed Black had a lifetime appointment to the Klan. Despite formally leaving in 1925, in 1926, he accepted a so-called "grand passport." Amid calls for his removal, Black pleaded his case in a radio broadcast (via History). An estimated 50 million people listened as he denied rejoining the Klan and described having black, Catholic, and Jewish friends.

The Bill of Wainwrights

As any Law & Order episode will tell you, a police arrest someone, among their enumerated Miranda rights is access to an attorney. If a detainee wants but can't afford legal counsel, it must be afforded to them, per Nolo. This wasn't always the case. In fact, as Oyez detailed, a 6-3 Supreme Court majority said quite the opposite in the 1942 case of Betts v, Brady. Arrested for robbery, Smith Betts requested a lawyer because he couldn't pay for one. The presiding judge proceeded to play "Jailhouse Rock" on the world's tiniest guitar, and Betts was sentenced to 8 years behind bars (via Justia).

Hugo Black belonged to the three-judge minority, writing in his dissent that "a practice cannot be reconciled with 'common and fundamental ideas of fairness and right,' which subjects innocent men to increased dangers of conviction merely because of their poverty." He would have his chance to change the court's tune in the 1963 case of Gideon v. Wainwright.

Per U.S. Courts, Florida authorities charged Clarence Earl Gideon with breaking and entering. He was too poor to afford a lawyer and thanks to a state statute, he didn't qualify for a court-appointed attorney. So Gideon, who only had an 8th-grade education, defended himself and received a 5-year sentence. The court voted unanimously to overturn Betts, with Black delivering the verdict.

The glaring Black eye on Hugo's legacy

It was a decision which would live in infamy. In 1944, a 6-3 Supreme Court majority sided with the Roosevelt administration in the case of Korematsu v. United States (via Justia). Hugo Black authored the majority opinion, condoning what was arguably the ugliest act of FDR's presidency. In 1942, on the heels of the Pearl Harbor bombing, FDR signed Executive Order 9066, and Congress passed the Act of March 21. Both related to relocation and detention of West Coast residents who had Japanese heritage. History recounted that the government instituted military zones so that civilians, most of them U.S. citizens, could be held in internment camps meant to preempt espionage for Japan.

Being 1/16th Japanese was enough to establish guilt by ancestral association. Often placed in repurposed horse stables, cow sheds, and other inhuman settings, roughly 117,000 people were uprooted. Fred Korematsu resisted and was arrested. Korematsu ultimately turned to the Supreme Court for justice, arguing that his Fifth Amendment right to due process had been violated.

Hugo Black reasoned that concerns about "disloyal" Japanese-Americans and immigrants warranted the government's actions. In a contemptuous dissent, Justice Frank Murphy said the decision "[fell] into the ugly abyss of racism." Even so, in 1967, Black informed The New York Times, "I would do precisely the same thing today."

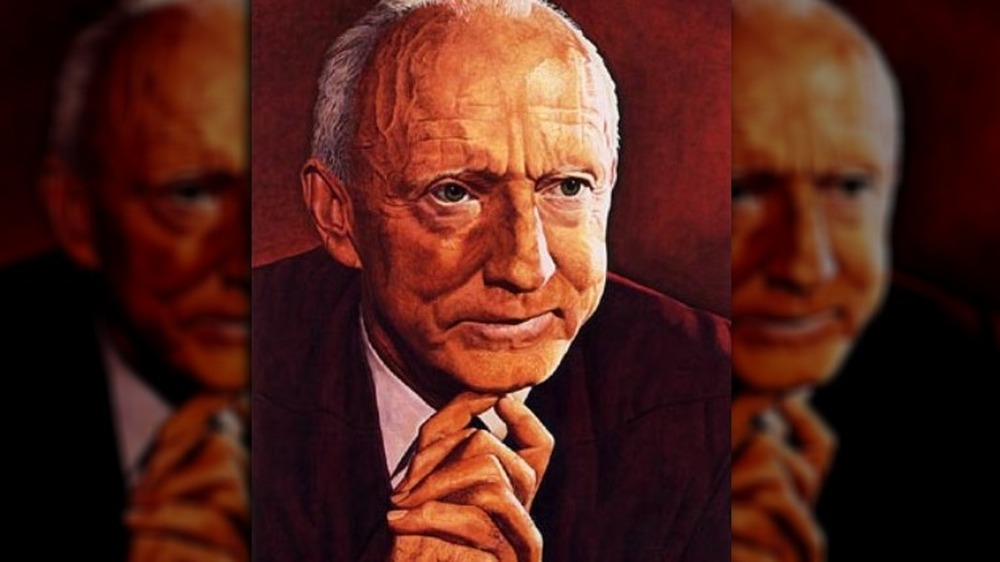

Hugo Black's dogma unleashed

Hugo Black and fellow SCOTUS bencher William O. Douglas envisioned a judiciary that actively expanded civil liberties and rights, butting gavels with more restraint-oriented justices such as Felix Frankfurter, according to ThoughtCo. The balance tilted strongly in Black's direction after Chief Justice Earl Warren joined the SCOTUS roster in 1953 and especially after Frankfurter retired in 1962 (via Thirteen and Oyez).

Warren was simpatico with Black, believing his chief responsibility was to "right wrongs." They would meet at Black's place for steaks, drinks, and night-long conversations. Early on, Warren asked Black to lead Court conferences, the sessions during which justices assess oral arguments and decide cases, per U.S. Courts. Warren grabbed the reins during Brown v. Board of Education, which sounded the death knell for school segregation – least legally.

Ordered to integrate "with all deliberate speed," resistant school districts vehemently dragged their feet. In 1959, Prince Edward County, Virginia decided to close its public schools altogether and operate whites-only private programs (via Justia). Black vented his frustration with the South's rebellion in the majority opinion for the 1964 case, Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward County, ordering schools to reopen and declaring that "the time for mere 'deliberate' speed has run out."

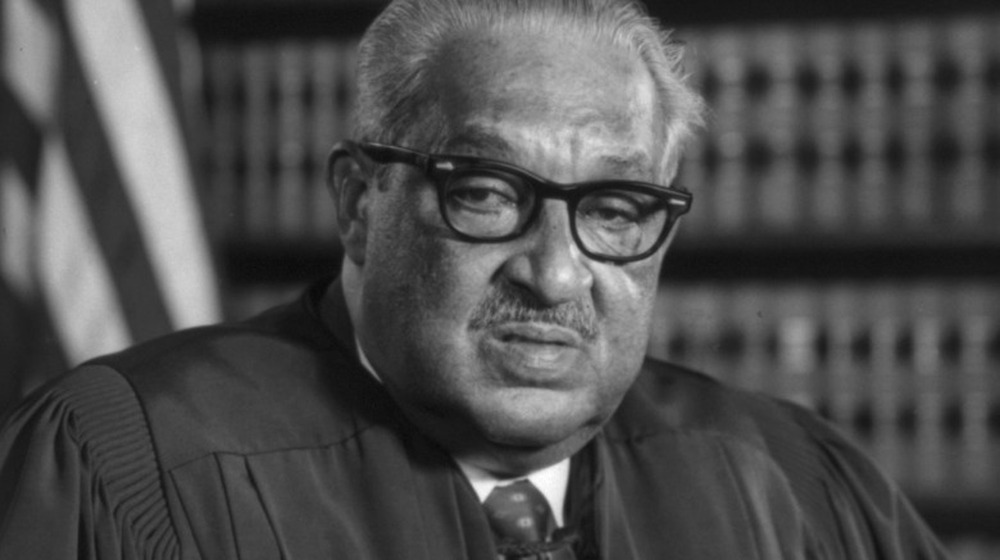

Hugo Black's relationship with Alabama heads south

When Thurgood Marshall ascended to the Highest Court in the Land in 1967, the famed NAACP lawyer asked none other than ex-Ku Klux Klansman Hugo Black to swear him in, per The Washington Post. Black had once declared that he could never have become a senator without the KKK's help (via Constitution Daily), and he reached the Supreme Court by impressing FDR in the Senate. Now, after using his gavel to hammer nails into the coffin of Jim Crow segregation, he was inducting the attorney who helped kill that racist system in the Supreme Court. It was justice at its most poetic.

But injustice did not go gently into the cold, dark night. It raged against the dying of white supremacy and perhaps even more so against Hugo Black. As recounted by PBS's The Supreme Court, in years following Brown v. Board of Education, his best friends abandoned him, and "a crowd tried to burn him in effigy on his front lawn" (via Thirteen). He donned a bulletproof vest just to set foot in Alabama. The former Klansman's two sons were caught in the crossfire and had to flee the state.

In 1959, Alabama's Senate passed a resolution stating that his "remains must never be buried in Alabama's sacred soil." Tuscaloosa News reported that Black was finally welcomed back in Alabama in July 1968, months after the assassination of MLK.

Amending Hugo Black's absolutism

The New York Times described the Bill of Rights as Hugo Black's "holy writ of, a set of 'absolutes' erected by the framers to shield and nurture individual freedom." And it framed the First Amendment as his first and foremost commandment. As chronicled by Cornell Law School's Legal Information Institute, Black vividly articulated his "absolutist" bent in multiple cases, in one instance writing, "First Amendment rights are beyond abridgment either by legislation that directly restrains" them or infringes upon them through "harassment, humiliation, or exposure by government." Author Steve Suitts told NPR that Black spent 20 years as a Baptist Sunday school teacher. Yet the first amendment was so sacred to him that he penned the opinion for Engel v. Vitale, the 1962 case which prohibited prayer in public schools (via Oyez).

Even so, Constitution Daily noted that Black bucked his absolutism in the 1969 case, Tinker v. Des Moines. Thirteen-year-old Mary Beth Tinker had been suspended from school for wearing a black armband to protest the Vietnam War. While most justices voted to uphold Tinker's right to protest, Black vehemently disagreed, blasting her actions as a distraction. Yale law professor Akhil Reed Amar argued that Black embraced the idea that "political and religious expression deserve very strong political protection," particularly unpopular speech. His talk of absolutism may have been a rhetorical tactic.

The free speech stalwart falls silent

Hugo Black spent 34 years on the Supreme Court and 85 years on Earth, according to The New York Times. Naturally, his judicial journey went out with a bang of the gavel. One of the final cases of Black's career involved the Edward Snowden of his time: Marine Corps officer turned military analyst Daniel Ellsberg. As explained by History, in 1971, Ellsberg shared portions of the now-famous Pentagon Papers with The New York Times, blowing the whistle on the government and blowing the minds of a war-weary public.

The Pentagon Papers exposed a marathon of lies about U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War across multiple administrations and demonstrated what Ellsberg saw as the conflict's futility. Watergate-keeper Richard Nixon didn't want any leaks raining on his reelection plans. So he tried to stop the press, setting up New York Times Co. v. United States. In its June 1971 ruling, a 6-3 SCOTUS majority said the government violated the First Amendment (via Justia). Black concurred with the verdict but argued that the Court shouldn't have even bothered hearing oral arguments because it delayed the publication of the Pentagon Papers, "[amounting] to a flagrant, indefensible, and continuing violation of the First Amendment." Hugo Black retired in September 1971 and died eight days later.