What It Was Like To Be A POW In The American Revolution

Imagine going into battle with high-waisted wool pants and a gun that only shot five bullets a minute. Luckily there was a 15-inch blade on the end of that gun, but then comes the problem of the white trousers. Undoubtedly, things were different during the American Revolution, from the fashion to how captive soldiers were dealt with.

Most probably recollect that the war had plenty of casualties throughout the seven-year conflict, however, the majority didn't take place on the battlefield, according to the American Battlefield Trust. It's estimated that up to 18,800 Americans died in the Revolutionary War, with up to 12,000 who were prisoners at the time. The British side isn't as well documented, but estimated overall deaths on their side come in around 24,000, including prisoners.

Both sides took in more prisoners than they had the resources for, and mass executions were understandably not going to go over well with Loyalists or Patriots, according to "Prisoners of War and American Self-Image during the American Revolution." The outcome quickly became bleak for POWs, whose experiences were well-documented for the American side due to a powerful mob of reporters and gut-wrenching narratives of those who made it out of captivity. As the poet of the American Revolution, Philip Freneau, penned, "Along the purling wave they think they lie, Quaff the sweet dream and all contented die; Then start from dreams that fright the restless mind, And still new torments in their prison find."

The British felt that Patriot prisoners had no legal rights to moral treatment

Keeping Patriot prisoners was complicated for Britain. Since the colonists were rebelling, the Brits felt like treating them as anything more than filthy traitors would basically legitimize America's efforts towards national autonomy, according to the National Library for the Study of George Washington. So, for the sake of semantics and to keep their entire premise for fighting the war solid, the Loyalists chose to recognize them as rebels.

Per the National Archives, George Washington had been voicing his grievances over the treatment of captured Patriots since the Revolution's beginnings in 1775, and threatened to retaliate if things didn't change. He wrote British commander-in-chief Thomas Gage — who was also an old pal from the French and Indian War — "If Severity, & Hardship mark the Line of your Conduct, (painful as it may be to me) your Prisoners will feel its Effects..."

Gage wasn't having it though, and wrote back to George that his men had been "...more comfortably lodged then the King's Troops in the Hospitals..." Gage also mentioned the word on the street was that British captives had been given the options to join the American cause, or grow their own food to keep from starving. The finger pointing went back and forth for years, until the first amicable prisoner exchanges were finally organized.

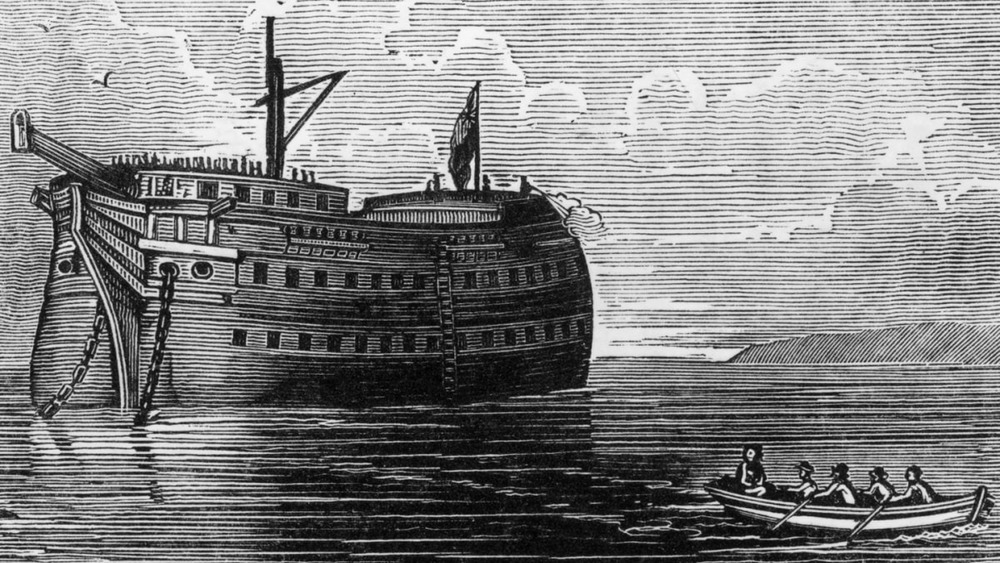

Ships were the main holding cells for American POWs

Although Britain maintained control of major cities throughout the war, they always seemed to be short of space for their ever-growing number of Patriot prisoners. They quickly turned to decommissioned Navy ships, both British and American, that lacked adequate space and simultaneously the prospect for successful escapes, according to "Prisoners of War and American Self-Image during the American Revolution." According to author Steve Sheinkin, one prisoner's account described how there was so little space in fact, that the hundreds of prisoners stuffed into the hull of one prison vessel didn't have enough oxygen to even light a match.

Per History, the ships became literal petri dishes for smallpox and typhoid fever that eventually prompted the daily routine call from British guards, "Rebels, turn out your dead." And if a prisoner wasn't enduring those diseases, they were certainly made susceptible to the rotten meat and meals made poisonous by cooking them in copper cauldrons with sea water, according to the Queen Sofia Spanish Institute New York. Per "In the Hands of the British: The Treatment of American POWs during the War of Independence," food and medical supplies were admittedly scarce for the British forces, and their own soldiers were understandably given first dibs on what became available during this hellaciously expensive war— especially since Americans cut off their resources and quit paying taxes and what not.

The majority of these floating torture chambers were anchored in Brooklyn's Wallabout Bay, and at the war's end in 1783, accounted for more than 11,000 deaths.

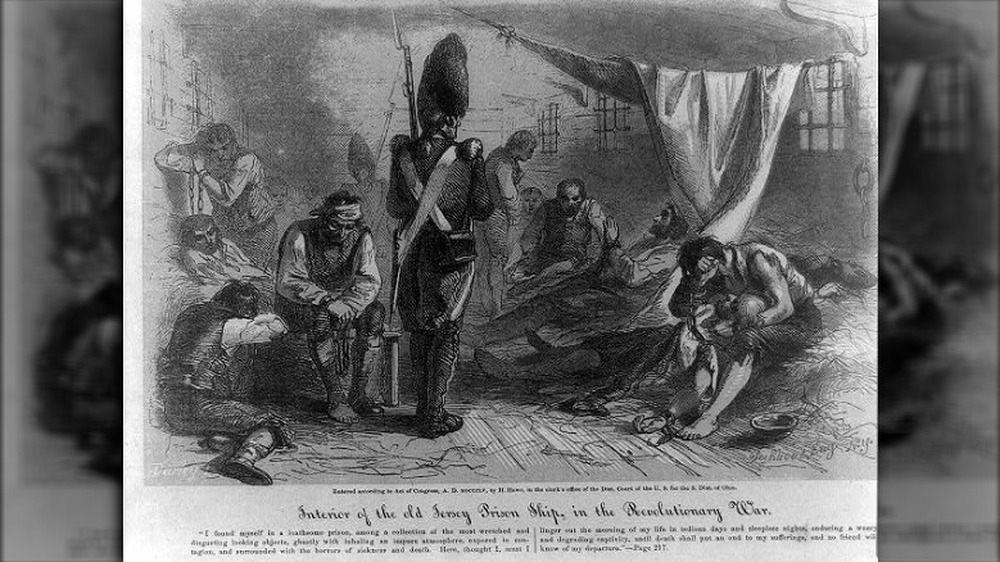

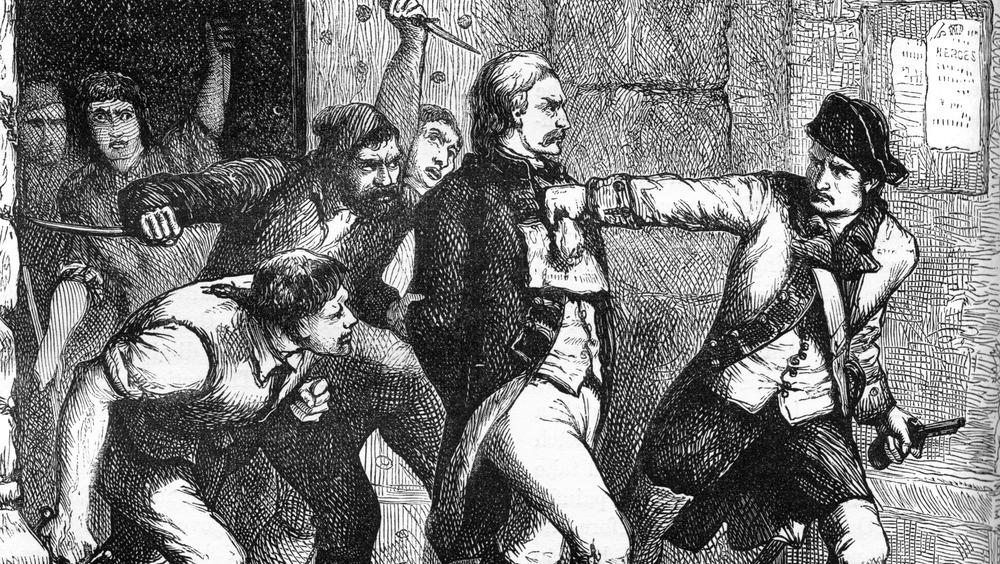

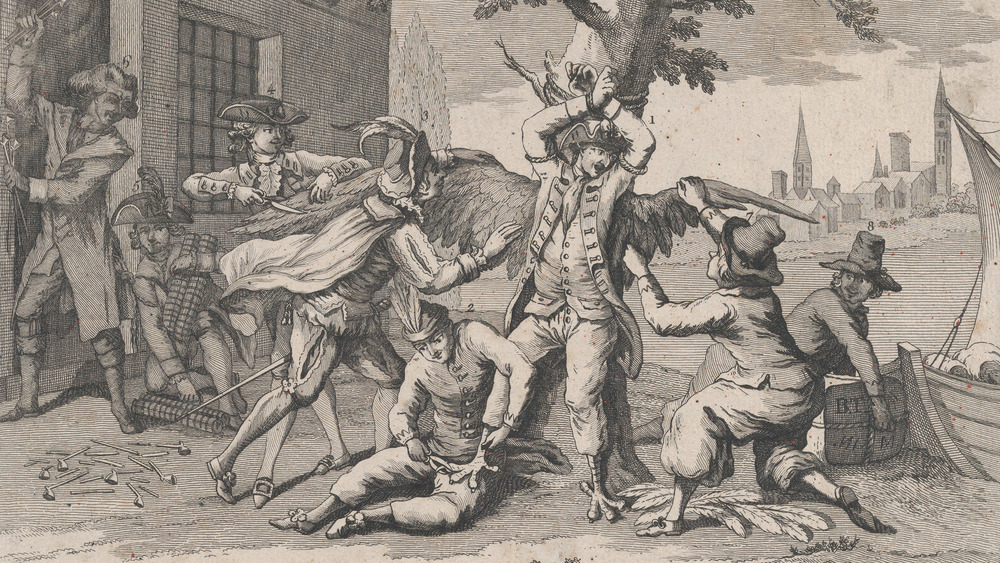

Prisoners were violently subdued

The Jersey was considered the most disgusting prison ship of the American Revolution, one reason being that the British guards were sourer than the bread they were feeding captives. A surviving prisoner named Ichabod Perry recalled in his memoir that there were so many prisoners the Loyalists stuffed below deck, they "...would punch them down with the breches of their guns." Christopher Hawkins, a prisoner who managed to make a rare escape from the Jersey, witnessed sheer morbidity from the British guards after a prisoner was caught stealing food from fellow captives. In his autobiography, he records how a guard tied down the man accused, and instructed other prisoners to beat him with a wooden rod: "the blood and flesh flying: ten feet at ev'rv stroke — during this period the defaulter fainted, but was resuscitated by administering water to him," only to be beaten more, and to die of his wounds a couple days later.

In George Taylor's Martyrs to the Revolution in the British Prison-ships in the Wallabout Bay, an especially gruesome night aboard the hell ship came when the prisoners decided to celebrate the Fourth of July. The British were unsurprisingly peeved as patriotic tunes emitted from below deck. The prisoners were told to cut it out by their keepers, but when they continued belting out their allegiance, the guards threw open the hatch and unsympathetically used the ends of their bayonets to quiet them. Many of the POWs died the following morning from their wounds.

Prison conditions were highly publicized

According to "Prisoners of War and American Self-Image during the American Revolution," the American Revolution was one of the first wars in history that heavily utilized the press to gain support. New England newspapers were also instructed by the Continental Congress to publish the letters exchanged between Patriot and Loyalist generals and commanders, which wasn't necessarily to showcase the values of truth telling in news telling, but to bolster support for the American cause. The Boston Gazette in particular was a pivotal mouthpiece of the American side of the Revolutionary War, and powered the state of rebellion against British rule before and throughout the war — especially with the help of hellacious prisoner accounts that made for very hot news, per the Journal of the American Revolution.

And as accounts of the hellish conditions American prisoners started rolling in, the British found themselves in a unique situation of having to defend themselves. In hopes to remedy more than bad press, British officials launched a supposed investigation into the ships of Wallabout Bay and came back with newly-free prisoner accounts. Apparently, the captives admitted that the vermin and disease riddled conditions were really their own fault, and they had plenty of food the entire time. Now whether the investigation was legit or not, such an effort indicates how influential and important the newspapers were for both sides of the war. Also, the press was unfazed by the report, and continued publishing POW horror stories.

Mental illness was common

Being starved, beaten, and neglected took quite a toll on the mental state of POWs in the American Revolution. Men who made it out to retell their stories, either to newspapers or on their own, illustrated a commonality of delusion. In The Adventures of Christopher Hawkins, Hawkins recounted that he saw a fellow prisoner, "on the fore-castle of the ship, with his shirt in his hands, having stripped it from his body and deli-berately picking the vermin from the plaits of said shirt, and putting them into his mouth." Another surviving prisoner, Ichabod Perry, said in his memoir, "We was then a little thin'd out, but not much re- liev'd for we had nothing to eat in four days after we went on board. I then saw the time that I could eat my own flesh without wincing."

Another captive aboard the Jersey named Thomas Andros said the guards would often taunt those suffering to put them in greater terror. From his compilation of letters, The Jersey Captive, he wrote, "Utter derangement was a common symptom of yellow fever, and to increase the horror of darkness which enshrouded us, for we were allowed no light, the voice of warning would be heard, 'Take care! There's a madman stalking through the ship with a knife in his hand!'" Delirium, hallucinations, and convulsions were a common sight among prison ships, most likely due to a combination of malnourishment, fever, fear, and trauma, per "In the Hands of the British."

Rebels often chose death

According to "Prisoners of War and American Self-Image during the American Revolution," it's estimated that up to a third of American prisoners refused to join the British army, despite the horrendous conditions they could have immediately unshackled themselves from. Every day, captives were propositioned with relief if they swore loyalty to King George III, yet thousands chose to die instead. According to "In the Hands of the British," some historians reason that the inflicted suffering of American POWs was more of a tactic of persuasion than limited resources since the British army was constantly running low on men. The British highly preferred recruiting young, resilient Americans than what was available to them back home, which was mostly middle-aged felons.

Accounts from unswayed prisoners, like Philip Freneau, reveal an intrinsic abhorrence for Britain— most likely fueled by the malignant treatment he endured aboard the Jersey. Christened as the Poet of the American Revolution, Freneau was a survivor of the most infamous prison ship of the American Revolution, and vividly recorded his experience with British brutality, per the National Humanities Center. Not-so-subtly from "The British Prison Ship," the poet showcases his feelings towards his keepers, "This selfish race from all the world disjoin'd, / Eternal discord sow among mankind; / Aim to extent their empire o'er the ball, / Subject, destroy, absorb and conquer all..." Freneau was certainly not alone in these sentiments towards Brits, as animosity had been building in the Colonies, France, and Spain since the 1760's when England tightened its leash on Ireland, the West Indies, and America, per Britannica.

Deceased prisoners were buried in shallow graves along New England shorelines

Dozens of Patriot prisoners died each day around New York, per "Prisoners of War and American Self-Image during the American Revolution." Dealing with their bodies became a half-hearted effort to properly dispose of them. Many bodies were dumped into Wallabout Bay, while others were given a dusting of sand along the shorelines. Prisoners were required to bury their own, and POW Captain Dring, via American Prisoners of the Revolution, recalled one of his afternoons digging holes hardly worthy to be called graves: "A single glance was sufficient to show us parts of many bodies which were exposed to view, although they had probably been placed there with the same mockery of interment but a few days before." However, he did say he was happy to finally have some fresh air.

General J. Johnson was a free Patriot who also took note of the exhibition that was unfolding along Wallabout's shores: "The bodies of the dead lay exposed along the beach, drying and bleaching in the sun, and whitening the shores, till reached by the power of a succeeding storm, as the agitated waves receded, the bones receded with them into the deep..." He also observed children playing with the skeletons and kicking them around with impeccable disregard. According to Smithsonian Magazine, many of the remains were collected and placed in a large crypt for a proper burial that today resides in Fort Greene Park in Brooklyn.

Some captives were shipped overseas

While many American prisoners stayed afloat on their own turf, plenty took trips across the Atlantic. Most had been sailors, some who would stay in better-kept jails in England and Ireland, or join the British navy, per "Treatment of American Prisoners of War During the Revolution." England's prisons were much more comfortable, giving Patriots access to medical attention, fresh air, and baths, per "Prisoners of War and American Self-Image during the American Revolution." They also didn't have to poop in a community tub as was expected aboard the vomit-scented, vermin-infested prison ships back in New England.

An early prisoner named Ethan Allen, a Colonel of the Continental Army, spent two years in English custody before being released on parole in New York, according to his own memoirs. While Allen's experience wasn't entirely smooth sailing (literally), his could be generally considered quite favorable to his counterparts. Allen recounted that while he first arrived in England, he joked around with the local visitors, drank punch, and wrote letters to the Continental Congress about retaliating if he were executed. As Allen expected, a British officer who proofread his note informed him that it was sent to the local Lord. Allen wrote, "This gave me inward satisfaction... for I had found I had come yankee over him, and that the letter had gone to the identical person I designed it for." At that time, America had more British captives of high ranks, and thus more leverage.

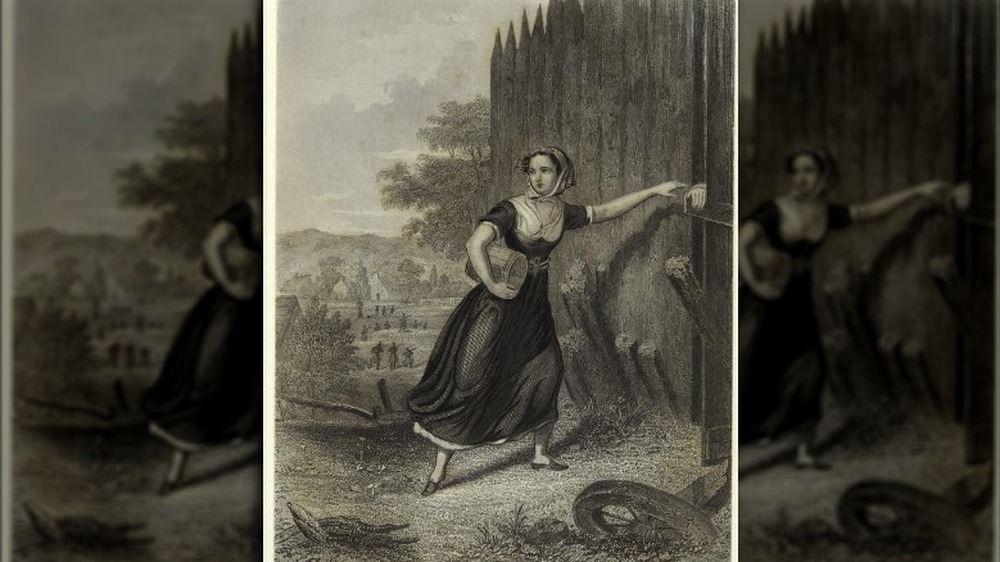

Elizabeth Burgin successfully smuggled Americans off prison ships

We often don't hear of heroines of the American Revolutionary War, but perhaps because they were so fabulously sneaky. Elizabeth Burgin certainly was, as she is somewhat of an elusive character of the Revolution but is undoubtedly considered a hero. While the widow and mother of three was living in New York, she was welcomed aboard the floating masses of misery in Wallabout Bay to feed and comfort prisoners, according to An Encyclopedia of American Women at War. Unbeknownst to the British guards, Burgin was quickly recruited by the Culper Spy Ring— the OG secret service of America— to peddle prisoners off these death ships. Miss Eliza, with the help of the ringleader Major Thomas Tallmadge, moonshined 200 American POWs out of Wallabout Bay.

The major's operation was quickly exposed however, and when British troops bagged him in his home, his wife panicked and blurted out that Elizabeth was an accomplice. But the Brits couldn't find her, and once she was safe in Philadelphia, she was left with absolutely nothing. In a time where women weren't considered for their service to military causes, she wrote the government repeatedly for remittance. They eventually obliged her, and made Elizabeth Burgin the first woman of the new nation with a pension for her service, per the National Archives.

Treatment of British POWs was a mixed bag

Even though George Washington was adamant about gifting British POWs with humane treatment, that wasn't entirely the case for all Englishmen in custody, per "In the Hands of the British." America most likely had a similar number of prisoners as the British, and were just as short on supplies, including food. The Patriots believed they had an innovative approach to this problem: Have the POWs grow it themselves! Prisoners were also given similar options as their Patriot counterparts, being that they wouldn't have to starve if they turned traitor.

One of the worst holding places for Loyalists was the Simsbury Mine in Connecticut. Per the Revolutionary War Journal, the old copper mine was renovated to house society's worst criminals, and Patriots felt that Loyalists fit the bill. The mine's interior was brimming with vermin, insects, and darkness. Although entering the chasm required being lowered into it from above, many miraculously escaped.

Per "Prisoners of War and American Self-Image during the American Revolution," Patriots were known to give preferential treatment to British generals by giving them their own places to stay and the freedom to roam around, as long as they gave an honorable word to not run away. However, things got pretty ugly in 1892 when Loyalists retaliated over the death of a British soldier by hanging an American general with a note pinned to him, "UP GOES HUDDY FOR PHILLIP WHITE." George Washington responded by personally picking out a British Captain, Charles Asgill, for execution, but didn't end up going through with it.