How The Green River Killer Was Eventually Caught

It's not clear how many women were fated to become victims of the Seattle-based serial killer dubbed the Green River Killer. While he hunted and killed mostly in the 1980s, victims are still being identified: In April of 2021, ABC News reported that a DNA match had led to the identification of a girl who was — so far — his youngest victim.

The match came with help from the DNA Doe Project, which searches public DNA databases in hopes of matching the genetic information of Jane and John Does with living relatives, in hopes of bringing closure to families. The Green River Killer case match was Wendy Stephens, a 14-year-old runaway who had fled her home in Denver for Seattle. She was killed in 1983, and disposed of in a forested area that's now SeaTac.

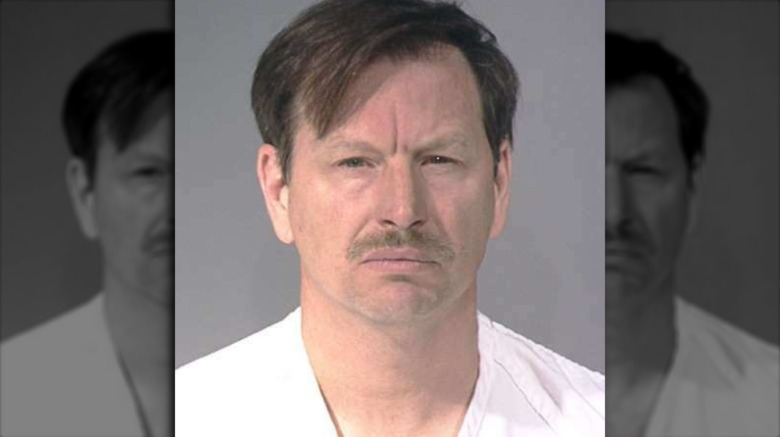

It took her family nearly 40 years to learn what happened to their daughter, and by that time, the Green River Killer had been behind bars for half that time. Longtime suspect Gary Ridgway wasn't convicted of dozens of murders until 2001 — decades after he first started killing. It took law enforcement ages to prove he was the one leaving a trail of bodies across the northwestern US, so what took so long? And how did they finally catch him?

The opening of the Green River Killer case

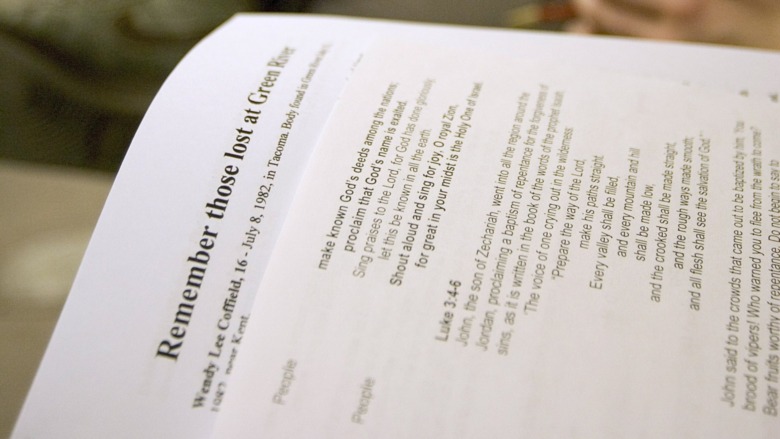

It's worth going all the way back to the beginning. According to History Link, Seattle law enforcement first realized that they had a serial killer on their hands when the remains of a 23-year-old woman named Debra Lynn Bonner were pulled from the Green River by a local slaughterhouse worker. She was found on August 12, 1982, and her death was almost immediately linked to the deaths of two other area sex workers, Wendy Coffield and Leann Wilcox. Coffield, The Seattle Times says, had been discovered on July 15 of the same year, and by August 16, the body count had risen to five.

It was going to get much, much higher.

Just over the next two years, 49 women would be discovered in the same area of Seattle: Most were sex workers, and most were well-known around the area of Highway 99 and the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport. The first is generally accepted to be Amina Agisheff, who was last seen in July 1982, but not found until April 1984. Among the last were 16-year-old Mary Exzetta West and 17-year-old Cindy Anne Smith, whose remains were found in 1985 and 1987, respectively. Other remains have yet to be identified.

Before the case was closed and before the killer was finally arrested, the area saw an investigation that cost upwards of $15 million, and man hours that were in the tens of thousands.

One of the original Green River Killer suspects

Just eight months after the investigation kicked off, police got a tip that started with the disappearance of 18-year-old Marie Malvar. According to HeraldNet, it was boyfriend Robert Woods who saw her getting into a pickup truck on April 30, 1983, with a man who looked to be between 30- and 40-years-old. They would never see her again. Woods would report her as missing four days later, but he — and Malvar's family — weren't the sort of people who were going to sit around and wait for a phone call. They started looking for the truck, recognizable because of the patches of primer. They absolutely found it: it was sitting in front of the house belonging to the man they'd see her with.

That was Gary Ridgway, and when police questioned him, he spent the entire time hiding the scratches Malvar left on his arm as he killed her. After convincing police he knew nothing about the missing girl, he went and buried her body. Malvar would ultimately be listed as the Green River Killer's 29th victim, and was one of 48 that Ridgway would later plead guilty to killing. Many died in the same house Woods and the Malvar family led police to.

Malvar's brother, Jose, later told The Associated Press, "I'm just angry about the whole thing — that they didn't arrest him when my dad brought the police over there. They should have done more follow-through. More lives could have been saved."

Taking a DNA sample

After the Malvar family brought Gary Ridgway to the attention of law enforcement, he always sort of hovered there. According to The Seattle Times, he even reached out to police in May of 1984, to see if he could provide any useful information, or assistance. At the time, he also took a polygraph test — which he passed.

(It's also worth noting that polygraph tests are dubious at best. Brandeis University's Leonard Saxe explained [via Vox]: "There's no unique physiological sign of deception. And there's no evidence whatsoever that the things the polygraph measures — heart rate, blood pressure, sweating, and breathing — are linked to whether you're telling the truth or not.")

Now, fast forward a few years, as the Green River Killer's body count continued to rise. It's April of 1987, and Ridgway isn't just a person of interest: he's also been identified as the last person seen in the company of at least two of the women who have since ended up dead. That's a little harder to write off as coincidence, even if someone confesses to frequently hiring the services of area sex workers — who make up the majority of the victims. According to HeraldNet, that's also when police pressed Ridgway for a DNA sample, in the form of saliva. He gave it — but this was also 1987, and DNA technology was nowhere near what it would become over the next decade.

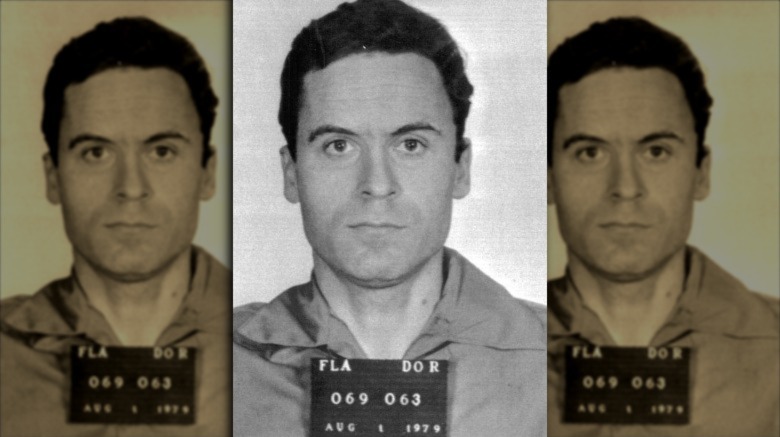

The serial killer who helped law enforcement with a psychological profile

Desperate times called for desperate measures, and at the time bodies started showing up in Seattle's Green River, there was another headline-grabbing serial killer sitting on death row. That was Ted Bundy, and in a bizarre twist, Bundy reached out to detectives and offered some help (via Biography). "Don't ask me why I believe I'm an expert in this area," he wrote to detective Dave Reichert, "just accept that I am and we'll start from there." They decided to take him up on the offer, and headed to Florida to visit the man who had been the country's most notorious serial killer... up until the Green River case.

Reichert would eventually credit his conversations with Bundy as giving them a unique insight into the mind of a serial killer, including the lack of remorse they felt at the killings, and the pride they took in claiming their work. Bundy also gave authorities a chilling tip on the killer he called the Riverman, saying he was likely to return to burial sites, where — should detectives stake out the scene — they would find him "performing sexual acts" on his victims.

Bundy was right. Ridgway would later confess to having post-mortem sex with 10 victims, and when arresting officers asked why he wouldn't just get another woman and kill her, he responded (via The New York Times), "Well, for one thing you'd have to pay for it and she was already dead."

A technological breakthrough in DNA technology

Fast forward a bit more, into the 1990s. The case was still open, and law enforcement had a slew of suspects — including Gary Ridgway — and they also had DNA evidence. Testing technology just wasn't there yet, and Washington State Patrol Crime Laboratory forensic scientist Beverly Himick put it this way (via The New York Times): "The case had basically come to a standstill."

It wasn't until 2001 that investigators got two new methods of DNA analysis dropped into their arsenal of forensic techniques. These two tests (called a polymerase chain reaction test and a short tandem repeat test) allowed for the sequencing and comparison of just fragments of DNA, and Himick says that's when they went back to the evidence, scrubbed it again, and came up with some samples from three of the serial killer's victims.

Remember that saliva sample that Ridgway gave in 1987? Himick used that to compare to the DNA samples recovered from the three women, and when she saw that it was a match, she knew they had their killer — and the evidence they needed to get him off the street for good.

A conveniently-timed arrest

When The Washington Post reported on the capture of the so-called Green River Killer in 2001, they started with his hunting grounds — a strip of highway they described as still being "a rough place where desperate women ply their trade." That strip, says History Link, was a section of Highway 99 (also called Pacific Avenue South) where down-on-their-luck women struggled to make ends meet as sex workers or dancers — and it's also where most of the Green River Killer's victims were picked up. And even though most of them were killed between 1982 and 1984, that's the same section of highway where 52-year-old Gary Leon Ridgway was arrested by a vice unit in November of 2001. The crime? "Loitering for prostitution."

At the same time he was arrested, Seattle crime labs were applying their new DNA testing methods to his old saliva samples — and to the DNA found on the murdered girls.

Reichert — the detective who had interviewed Ted Bundy about the Green River Killer — was King County Sheriff at the time he made the announcement, saying, "This has got to be one of the most exciting days of my entire career. This is not only an exciting day for the people who worked the case, but I know the community has got to be as excited about this as we are."

How close had they gotten to the Green River Killer?

Gary Ridgway had been a suspect in the killings for 18 years when he was finally arrested. They'd talked to him a lot, and according to The New York Times, Ridgway had taken (and passed) two polygraph tests, and he'd been questioned by police countless times — so many times, in fact, that his coworkers at the trucking company he'd worked at for around three decades had taken to calling him Green River Gary. Sometimes, they just called him "GR."

While Ridgway had never been charged with the Green River killings, he still had some run-ins with the law. In 1980, The Washington Post says that a sex worker accused him of choking her. The case disappeared, but his later confession (via CBS) puts that in a terrifying perspective. He wrote in his formal statement, "Choking is what I did and I was pretty good at it," adding that he targeted mostly sex workers and runaways, and that he would revisit the bodies "for two or three days... till the flies came."

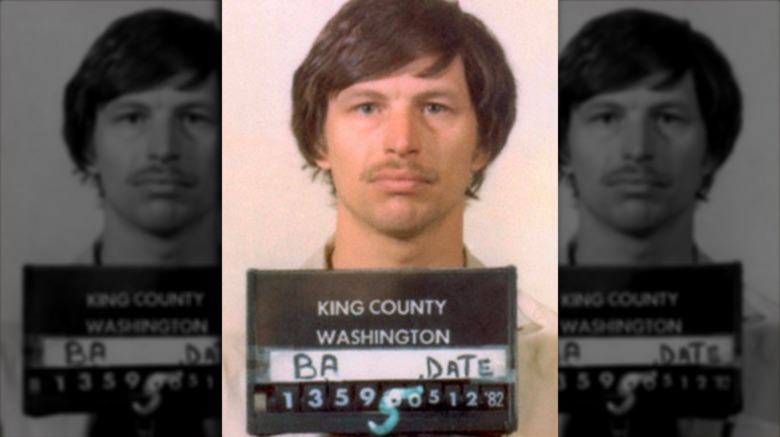

In 1982, Ridgway was charged and convicted — of solicitation, when he approached an undercover police officer (mug shot, pictured). But those who knew him had another problem with him: he and his wife had cut down a forest of trees on their property when they moved in, but ultimately, they got used to seeing him walking his poodle around the neighborhood. Even after his arrest, they described him as basically a "nice guy."

The 1984 letter

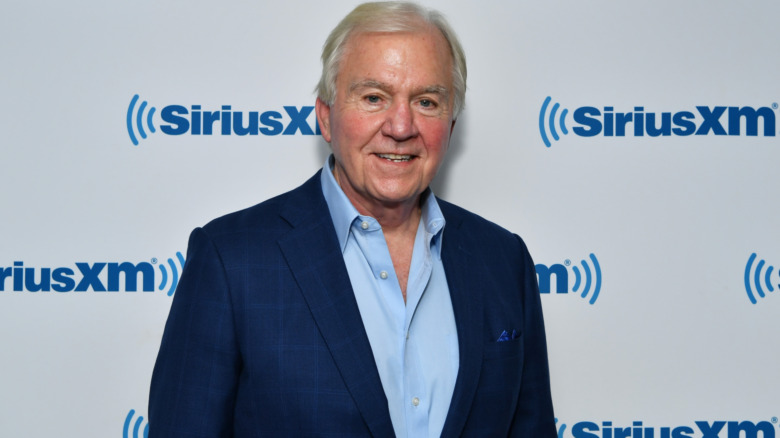

The Green River Killer was allowed to keep killing for so long in large part due to a lack of evidence. But strangely, law enforcement had one massive piece of evidence that they completely overlooked — on the guidance of one of the industry's most well-known criminal profilers, John E. Douglas (pictured). And yes, that's the guy that wrote Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit (which was the basis for the Netflix show of the same name), and who Vulture says pretty much wrote the book on serial murder investigations, with some help from interviews with some of the most notorious murderers ever put behind bars.

The Seattle Times says that a letter was postmarked February 20, 1984 and sent to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. It included a ton of disturbing details that hadn't been made public, but Douglas shrugged it off by calling the writer "a subject who is average in intelligence and one who is making a feeble and amateurish attempt to gain some personal importance by manipulating the investigation."

Later, as part of his confession, Ridgway confirmed that the letter was his — even though he didn't really remember writing it. While Douglas said that he didn't think his misidentification of the letter made a difference in the time frame of the killer's capture, he also added, "I truly believe that he could have been caught sooner."

The Green River Killer's confession

When it came time for Gary Ridgway to go to court, the names of all 48 victims of the Green River Killer were read aloud and, in a process that took almost 10 minutes, CBS reports that there was a pause after each name — long enough for Ridgway to enter his "guilty" plea. Admitting his guilt kept him off death row, but there was more to it: Ridgway promised to bring closure to dozens of other unsolved murder cases, including an original seven more that law enforcement said they had evidence he was involved with.

And it seemed that about this, at least, he would tell the truth. When law enforcement presented him with one case, he denied it was his for a chilling reason (via The New York Times): "Why, if it isn't mine? Because I have pride in — in — what I do. I don't wanna take it from anybody else."

He went on to call (via The Washington Post) killing his "career," and not only took pride in his murderous work, but in something else chilling. He kept no trophies, but if his victims were wearing jewelry, he did take that — and then would leave it in the Kenworth Motor Truck plant women's bathroom. "My favorite thing was maybe if someone's walking around with a piece of that jewelry that they found in the bathroom."

The Green River Killer explained how he covered his tracks for so long

So how on earth did the Green River Killer manage not to leave any evidence behind for so long? According to The Washington Post, he told investigators all about that, too. In addition to taking precautions like always wearing gloves, he added some incredibly devious tactics to his arsenal. Those scratches on his arm from Maria Malvar, the victim with the vigilant family who led police right to him? He spilled battery acid over the wounds to hide what they really were.

He left cigarette butts and chewing gum wrappers at the dump sites as misdirection, because he didn't use either, he regularly changed the tires on his truck, and on the occasions when he hurt himself while getting rid of a body, he'd claim it was a work injury, then file a workers' comp claim so there was a paper trail. He also made sure not to kill anyone that could be connected to him, even though he confessed that he had considered killing his mother, his second wife, third wife, and his son.

And most importantly? He kept his mouth shut. University of California, San Diego forensic psychologist Reid Meloy explained Ridgway this way: "His containment is amazing, especially given his pride in what he did. To have strong feelings of pride in one's career as a serial murderer and then not communicate that to anyone for 21 years is a measure of remarkable discipline."

The sentencing of the Green River Killer

Gary Ridgway was handed a life sentence in 2003, and according to The New York Times, his admission of guilt in 48 murders made him "the most prolific convicted serial killer in the nation's history."

At his sentencing, he shed some tears and hinted at the fact that he was sorry about "the ladies who were not found," saying, "May they rest in peace. They need a better place than where I gave them." At the time, prosecutors say they were already aware of another dozen cases that Ridgway was involved in: hence, the plea deal that kept him off death row. But there might just be a catch.

King County Sheriff Dave Reichert clarified for CBS, saying that the plea deal didn't protect him infinitely, and if he was tried and convicted of murders in — for example — another state, he still might end up being handed the death penalty. Still, that was small comfort for the relatives of his victims, like Kathy Mills. Her 16-year-old daughter was among Ridgway's victims, and she was in the courtroom as he confirmed his guilt. She said, "It was hard to sit there and see him not show any feeling and not show any remorse."

Are there more bodies?

In 2003, Ridgway did, indeed, start talking to law enforcement about the still-missing bodies of more women he'd killed. According to ABC News, that led to the discovery of four more of his victims. But then, funding started to dwindle, and efforts to recover his other victims ceased.

Until 2013, when privately-funded investigations picked up where law enforcement left off. Guided by Ridgway's original confessions and phone conversations, former Air Force criminal investigator Rob Fitzgerald and his team continued to search for more remains... while admitting that they knew much of what Ridgway was telling them was probably lies. Still, they were hopeful for even the smallest bit of truth, and the promise of bringing closure to some of the victims' families.

And according to Ridgway, there's a lot more. After saying that he's a changed man now that he'd found God, he told Washington state reporter Charlie Harger, "The total number is 75 to 80."