What It Was Really Like The Day Abraham Lincoln Was Assassinated

For most people on the morning of April 14, 1865, there was probably little to note about the day, apart from the fact that it was Good Friday and they would be celebrating Easter in a couple of days. In fact, for quite a few Americans, it may have seemed like a pretty good day. According to Weatherwise, it was probably a nice, warm spring day in the nation's capital of Washington, D.C., a complement to what many must have assumed were decreasing tensions that had torn the country apart.

Per History, the American Civil War had just concluded with the surrender of Confederate forces by Robert E. Lee at Virginia's Appomattox Court House on April 9. Less than a week later, it wasn't entirely clear how the nation was going to rebuild after such a long, bloody, and traumatic war amongst its own people, but it may have seemed at least like Americans could take a moment to breathe.

Modern Americans, however, know that this warm spring day would end in tragedy for President Abraham Lincoln, his family, and the rest of the nation. For, while some might have been relaxing, Southern sympathizer John Wilkes Booth and his associates were planning to enact a series of blows meant to crush the newly-restored American government. By the evening, Lincoln would be shot, his Secretary of State stabbed, and the U.S. would find itself reeling from the first successful assassination of an American president in history.

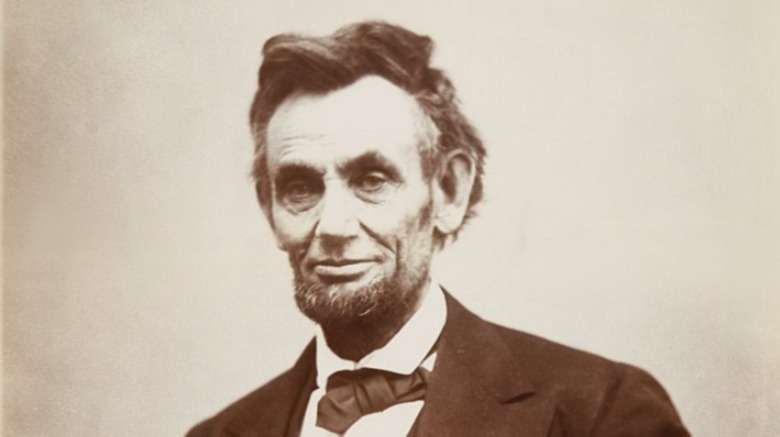

Abraham Lincoln may have thought it was going to be a good day

The morning of April 14, 1865 seemed to have been a pretty cheerful one, at least within the confined of the White House. Multiple observers that day noted that Lincoln was in an especially good mood. Seamstress Elizabeth Keckley, a former slave and confidante of Mary Todd Lincoln who was often in the White House, recalled in "Behind the Scenes" that "[Lincoln's] face was more cheerful than I had seen it for a long while, and he seemed to be in a generous, forgiving mood."

Even Mary noted that her husband was especially cheerful, as Smithsonian Magazine reports. On a carriage ride, he was so happy that she playfully remarked, "Dear Husband, you almost startle me by your great cheerfulness." With the American Civil War officially over and his oldest son Robert safely returned from his post as a staffer for General Grant, Lincoln may have finally felt like he could relax a bit. That's certainly what he told his wife, remarking that, after the stress of the war and of their own son Willie's death, they both should try to be happier. And a nice visit to the theater later that evening would be just the thing to help them both laugh and relax.

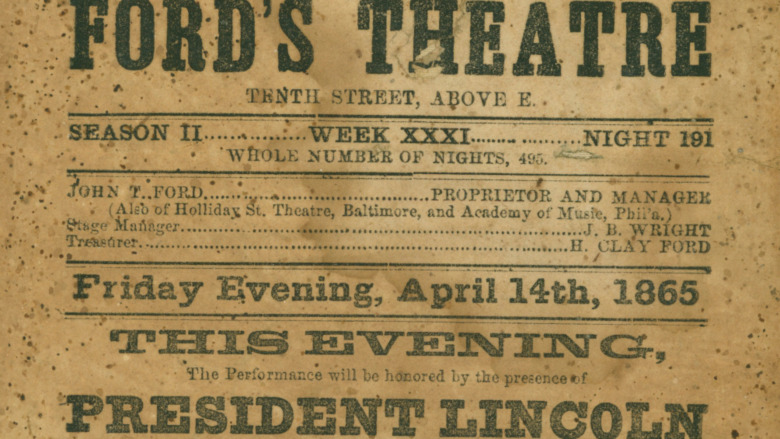

The Lincolns arrived late to the play

Later in the evening, President Lincoln and his wife intended to watch a play with two friends: Clara Harris, the daughter of one of Mary's friends, and her fiancé, Major Henry Rathbone. As Smithsonian Magazine reports, they had an early dinner and then headed to Ford's Theatre on Tenth Street, to watch "Our American Cousin," a comedy. Lincoln had actually invited quite a few other people, including Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax and General Ulysses Grant and his wife. All but Harris and Rathbone declined for various reasons, including some who thought it not entirely appropriate to watch a play on Good Friday.

Though the group was late to the play, it was clear that the regular folks inside the theater were eager to see the president. As the Lincolns made their way to their seats in a stageside box draped with patriotic bunting, the theater's musicians began to play "Hail to the Chief," the song still often used today to announce the entrance of a U.S. President at an event.

That night, the audience rose to their feet, applauding, while Lincoln bowed and then sat in an armchair. Newspapers had actually advertised that the Lincolns would be attending, meaning that at least some of the people in attendance surely snagged a ticket so they could get a glimpse of the president.

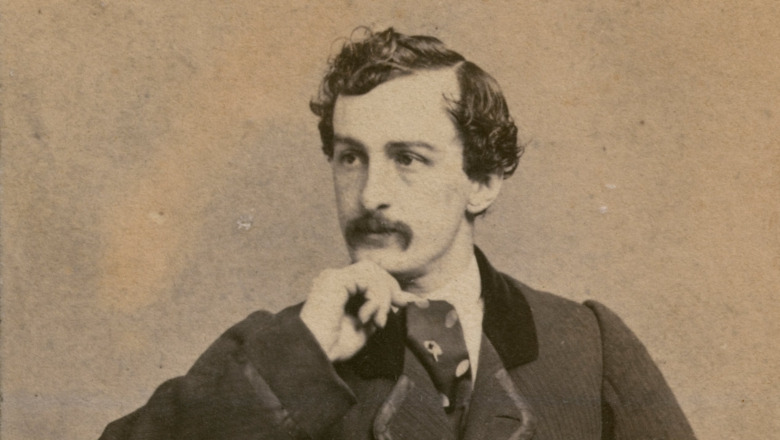

It was easy for John Wilkes Booth to sneak into the president's theater box

Actor and Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth also knew that Lincoln would be at Ford's Theater, though he wasn't there when the president's party took their seats. Instead, according to History, Booth started off the night by drinking at a nearby saloon. But, while the booze he was imbibing may have given him some unfortunate liquid courage, he may not have been able to make it into Lincoln's theater box if it weren't for another unwitting player: the president's guard.

Said guard, John Parker, was apparently not a fan of "Our American Cousin." As a result, he had gotten bored and wandered away to grab a beer. According to Smithsonian Magazine, he was a local cop with an inconsistent record. It was an odd choice, though Lincoln and other politicians of the 1860s were often cavalier about their personal safety.

Still, it was a bit odd that a subpar guard was the only person guarding the box that night, especially given that Lincoln wouldn't be the first president to face an assassination attempt. American Heritage reports that President Andrew Jackson survived an 1835 attempt on his life when the assassin's pistols misfired. Regardless of whether or not that was on Lincoln's mind, Parker left, and Booth easily made it all the way through the crowded theater and into the president's box.

Booth used the play and theater audience to his advantage

While John Wilkes Booth was a recognized actor, he was always seemingly in the shadow of his more famous and arguably more talented older brother, Edwin, at least according to the Folger Shakespeare Library. But, regardless of his aptitude, the younger Booth was still a working actor who was familiar with the play "Our American Cousin."

Booth knew that he could wait until a well-known line that would make the audience laugh, more or less covering the sound of his entrance, though it likely wouldn't have covered the sound of his gunshot for those in the theater or at least the immediate vicinity of the president.

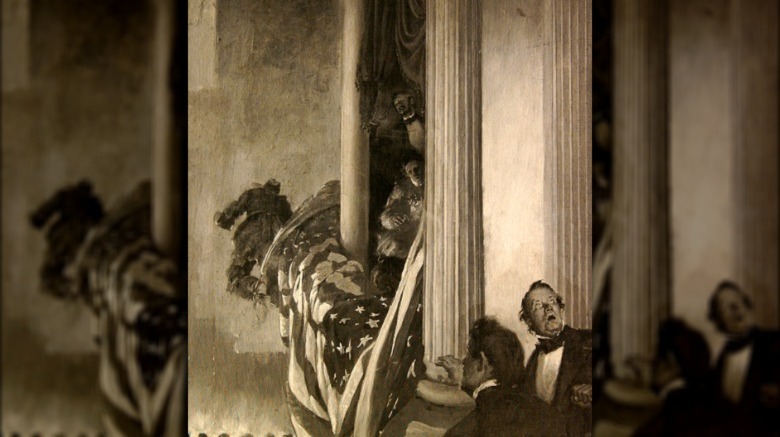

Accounts of what happened next are pretty vague or even, in some cases, contradictory, Vox reports. We can be sure that, as the realization that something horrible had just happened to Lincoln dawned over the audience and the single actor on stage, Booth somehow got out of the box and onto the stage. He had to exit that way because he'd blocked the entrance to the box — helpful audience members had to practically break down the door to get to the wounded Lincoln afterward.

One man in the president's group tried to fight Booth

Major Henry Rathbone, the Union Army officer who attended the play with the Lincolns and his fiancée, Clara Harris, was one of the first people to react to the president's shooting. In the space of a few moments, Rathbone stood up and may have attempted to stop Booth. However, according to American Heritage, Booth not only had the pistol he used to shoot Lincoln, but a knife, too. He lashed out, cutting Rathbone deeply across the arm, then escaped.

At first, in the tumult of realizing just what had happened to Lincoln, it seemed as if the Major was injured but ambulatory. According to "Lincoln's Last Breath," Rathbone was able to escort Mary Todd Lincoln across the street where her husband was taken. However, Rathbone then passed out from blood loss, leaving a lot of his own blood on the screaming First Lady. Unlike the president, he survived, but seemed to suffer psychologically from the events of that day.

American Heritage reports that Rathbone believed that he could have somehow saved Lincoln, even though it's not clear how he could have done so. He began to suffer from a series of physical and mental ailments, which grew so bad that he shot his wife Clara to death in 1883. Rathbone spent the rest of his life in a mental asylum.

No one is sure how Booth managed to escape a theater full of people

The particulars of how Booth managed to make his way to the stage are jumbled, speaking to the immediacy of the events and how different stunned audience members recalled that night. According to Vox, we know he made the approximate 12-foot drop to the stage somehow. Some think Booth must have clambered down using the bunting draped in front of the box, while others say he jumped.

In his diary, Booth claimed that he broke his leg as he leapt onto the stage, as History reports. Others reported seeing him run as if uninjured. Many accounts also claim that Booth shouted something, either right before he shot Lincoln or as he stood on stage, poised to escape. Yet, few people who were there agree on what he shouted, whether it was "sic semper tyrannis" ("thus always to the tyrants"), "freedom" as Rathbone reported, or nothing at all.

Whatever happened, Booth encountered practically no resistance within Ford's Theatre, perhaps because he was waving a knife. Actress Jeannie Gourlay, who had left the stage only moments before the shooting, later recalled that Booth ran towards them "waving a great knife. He dashed between us toward the stage door, thrusting me aside with one hand and slashing at Mr. Withers [the orchestra conductor] with the knife." At this point, few people outside of the theater knew what had just happened inside.

A doctor made it clear that Lincoln was dangerously wounded

While many of the audience members were understandably in shock once they realized that Lincoln had been shot, some were able to leap into action. This group included Union Army surgeon Charles Leale, who was able to make his way to the box and offer his help.

Leale wasn't exactly there by accident. According to an 1865 report written by him and discussed by the Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, Leale had actually heard Lincoln address a crowd earlier. Struck by the president's manner, he decided to attend the same play that Lincoln was going to watch. After hearing the gun shot and watching Booth flee off stage while brandishing a knife, Leale wrote that "I then heard cries that the 'President had been murdered,' which were followed by those of 'Kill the murderer,' 'Shoot him,' etc, which came from different parts of the audience."

As American Heritage reports, Leale found that Lincoln had no detectable pulse. Leale found the entry hole in Lincoln's skull and placed his little finger in the wound. He had assumed that the president was already dead but, when he was done probing Lincoln's gunshot wound, movement indicated that the president was still alive. Leale's immediate treatment allowed Lincoln to survive until the next morning, though some argue that his unsterile methods would have eventually caused a deadly infection.

People carried Lincoln across the street to a boarding house

As the clock ticked on after the shooting, more and more people in and around Ford's Theatre realized what had happened. First, however, it was necessary to get the still-living Lincoln somewhere to be potentially treated — or at least to keep him comfortable as he died. Per the National Park Service, the injured and unconscious Lincoln was carried across the street to what's now known as the Petersen House, a lodging house. Lincoln was placed in a bed in the back bedroom, while the Petersens and other lodgers stayed in the basement.

As for the other audience members, few seemed to know what they should do in the aftermath of such a shocking and traumatic moment, much less one that was going to be a pivotal piece of American history. Some dazedly wandered out of the theater and into other establishments. As quoted in "We Saw Lincoln Shot," Laura Freudenthal, who was sitting in the audience that night, said of her group that "we just couldn't go home like that for we were nearly frantic, so we walked down to Harvey's [a restaurant]."

Soon enough, according to her account, more and more people in the city knew what had happened. "When we had quieted down a bit, we went outdoors again to go home ... Everybody seemed to be out; soldiers were milling about and the excitement was something terrible to behold!"

Mary Todd Lincoln was overwhelmed with shock

Mary Todd Lincoln, who was sitting next to her husband when he was shot, did not react to the assassination with calm. Mary would later be criticized for the "undignified" way she dealt with her husband's sudden death. Never mind that she had also dealt with the deaths of two sons and the nationwide trauma of the war. Mary was already something of a controversial figure for Washington busybodies, according to History. She had a forceful personality, a love of the spotlight, and an even greater love of spending money. Her overwhelming grief the night of Lincoln's shooting was taken as further evidence of her embarrassing behavior.

She reportedly did not hold back her emotions as she moved between the back bedroom of the Petersen House to the home's front parlor. Her sobbing and wailing was so upsetting to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton that he even banished her from Lincoln's bedside in the early hours of the morning, according to "Ford's Theatre." She was not to return to the room, even once it became clear that Lincoln was taking his final breaths.

Later, Mary was rather unceremoniously herded out of the White House after much resistance on her part. As Biography reports, President Johnson never paid her a visit or event sent a note in the aftermath, which Mary took poorly. She would later insinuate that Johnson was somehow involved in the plot to kill Lincoln.

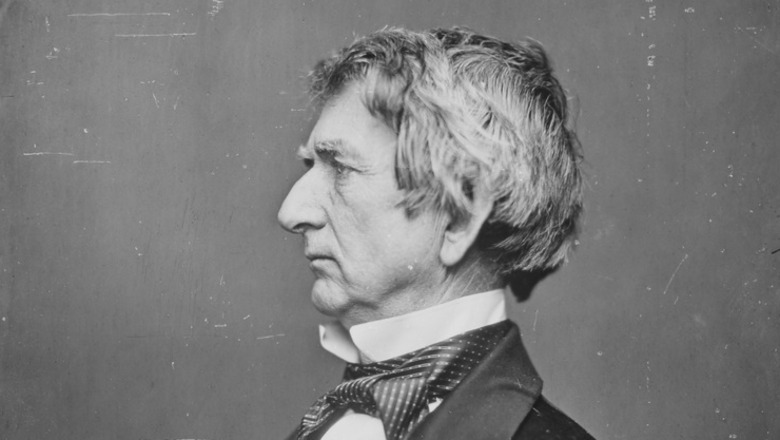

Lincoln's Secretary of State was nearly also assassinated that day

Though, to people who were at Ford's Theatre the night of April 14, 1865, it may have seemed as if a lone gunman had just shot the president, Booth's actions were actually part of what was to be a coordinated effort to bring the government to its knees. Yet, Lincoln was the only one who would die as a result of Booth's conspiracy.

For a frantic few hours, however, it seemed as if Secretary of State William Seward was going to be the second casualty of the night. According to CBS, Seward was in bed recovering from a carriage accident when a man named Lewis Powell entered his home and stabbed the secretary. He also stabbed six other people, including one of Seward's sons and his daughter, and also gave another of Seward's sons a fractured skull. Powell was eventually captured and hanged along with other conspirators on July 7, 1865. Somehow, no one died from his attack, including Secretary Seward, whose splints and bandages had actually deflected the blade and saved his life.

Vice President Andrew Johnson was also the subject of yet another arm of the plot, though the prospective assassin, George Atzerodt, chickened out at the last minute. Per Ford's Theatre, Atzerodt was eventually targeted by a hotel employee for looking "suspicious." His room was searched, he was arrested, and, though he never carried out the plans against now-President Johnson, Atzerodt was executed anyway.

Lincoln died the next morning as a room full of people watched

After lingering for hours in the back bedroom of the Petersen House, Lincoln finally died on April 15, 1865, at 7:22 am, per Ford's Theatre.

For the various people gathered in that room, there was no sudden or dramatic end to the president's life, NPR reports. Charles Leale, the young physician who had first treated Lincoln on the floor of the presidential theater box, wrote that, after Lincoln's stopped breathing for a few moments, "all eagerly look at their watches until the profound silence is disturbed by a prolonged inspiration." Three people monitored Lincoln's steadily weakening pulse at three different points on his body, including Leale at his right side.

According to the U.S. National Library of Medicine, his body was taken to the White House for an autopsy. There, Union Army Surgeons Edward Curtis and Joseph Janvier Woodward, along with the Surgeon General and a small group of other men, confirmed that the gunshot wound ultimately ended Lincoln's life. Vice President Johnson took the oath of office at 11:00 am.

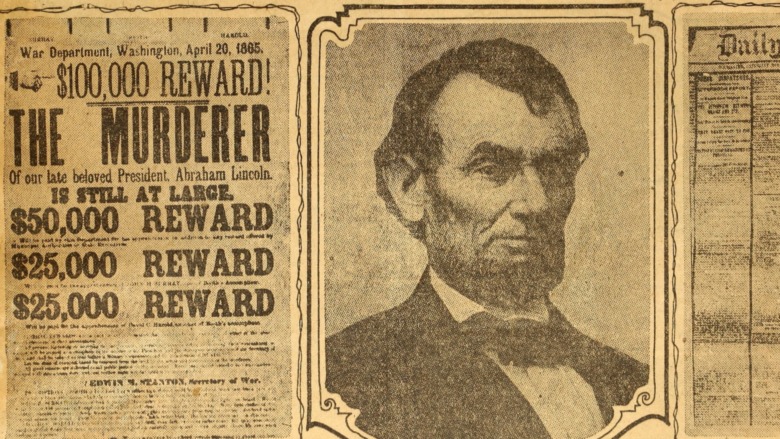

Not everyone knew right away that Lincoln had died

The news of Lincoln's death was disseminated unevenly. Neither was it always fully accepted by the people who first heard it. The telegraph made it so newspaper reports of Lincoln's death appeared very quickly, Vox reports, but not everyone believed it or got the news the same day. In the South, which was still reeling from the disastrous effects of Union occupation and Sherman's March to the Sea, communications equipment like telegraph lines were badly damaged.

Some people simply received the news from their neighbors, who were either celebrating or mourning as they saw fit. Surprising as it may be to modern Americans, who routinely rank Lincoln as one of their best presidents, according to C-SPAN, his reputation in 1865 was more uneven. An intense civil war doesn't necessarily boost one's approval ratings, after all.

Eventually, more and more newspapers began to report that the president had been assassinated. Smithsonian Magazine reports that even some people who had been critical of Lincoln just a short time before soon began displaying their grief at his death in a very public way. The funeral procession that would eventually carry Lincoln's embalmed body from Washington to Springfield, Illinois was witnessed by thousands of openly mourning Americans — though, as the National Museum of American history notes, the route did not take Lincoln's remains through the ravaged and far less friendly South.