The Tragic True Story Of Hawaii's Massie Trial

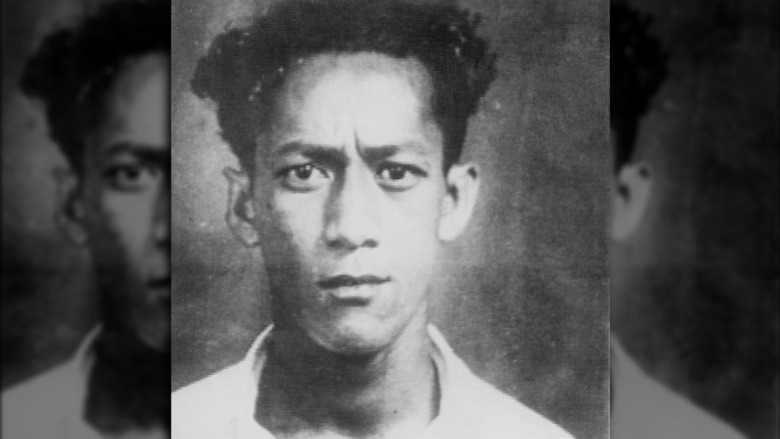

In 1932, Joe Kahahawai Jr., a Native Hawaiian, was murdered after being acquitted of raping a white woman. Although there was never any evidence to support the idea that Kahahawai or his four co-defendants were responsible for assaulting Thalia Massie, many in the white community of Hawaii and the mainland United States considered his murder a justifiable "honor killing." Meanwhile, non-whites recognized the lynching and the moral panic that it stemmed from.

No one knows what exactly happened to Kahahawai's alleged victim Thalia Massie on the night of September 12th, 1932. And recently, scholars have suggested that during the rape trial and the subsequent murder trial, "all six became pawns in a system that ultimately served the white male power structure." But in the end, Kahahawai was the one who lost his life to vigilant violence that was essentially condoned in both the courtroom and the court of public opinion.

This is the tragic true story of Hawaii's Massie murder.

What happened to Thalia Massie?

Thalia Fortescue married Lieutenant Thomas H. Massie when she was 16-years-old, and early on they had a difficult marriage. She'd often leave parties whenever she desired, which caused Tommy to threaten her with divorce, since "socializing and entertaining were required to further a Navy career," according to PBS.

On the night of September 12th, 1931, Thalia Massie got into a fight with Tommy around midnight and after slapping him across the face, she left the Ala Wai Inn in Honolulu in the Territory of Hawaii. According to "The Massie Case," Thalia was picked up roughly one hour later as she walked down "an isolated and unlit portion of Ala Moana Road" by couples named the Bellingers and the Clarks. When the car stopped, Thalia asked if the people in the car were white. She reportedly asked this "because she had very poor eyesight," but this fact wouldn't arise until later in the trial.

Thalia had a bruised face, and when asked what happened she said that five or six "dark-skinned Hawaiians" had forced her into a car and beaten her. When asked if anything else happened, Thalia said no, and claimed that since it was dark, she had been unable to see the license plate number of the car. Although the Bellingers and the Clarks told Thalia that she should go to the police or at the very least the hospital, she refused and asked them instead to take her home.

'Something Terrible has Happened!'

When Tommy Massie called home later that night, Thalia said to him "Something terrible has happened!" Tommy claimed that upon arriving home, Thalia told him that she's been assaulted and raped by five Hawaiians by Ala Moana Road.

A quarter before two in the morning, Tommy called the police to report that his wife had been assaulted and police officers arrived at her house within half an hour. "The Massie Case" explains that Thalia told the police that she'd been kidnapped while walking on John Ena Road, and after being beaten in the car, she had also been gang-raped. "She said she did not know the license number of the car and she could not visually recognize the perpetrators but could recognize their voices."

She also said that she couldn't recall or give descriptions of her assailants, other than the fact that they were Hawaiian, "which she could tell from their voices," and that one was called "Bull." Although the police officers repeatedly asked Thalia about the license number of the car, Thalia repeatedly and clearly stated that she couldn't identify the license number.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

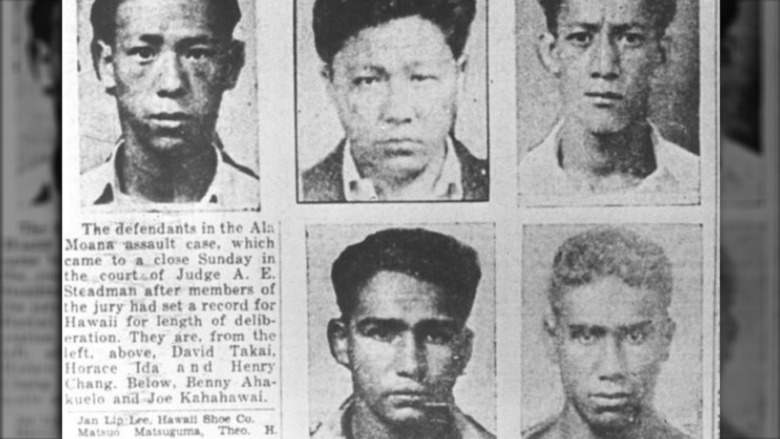

A near-miss traffic accident

That same night, around 12:35 AM, while a different couple, the Peeples, were driving through downtown Honolulu, they had a near-miss traffic accident with a car carrying five young men: Joseph Kahahawai, Benny Ahakuelo, Horace Ida, David Takai, and Henry Chang (pictured). After the cars barely avoided colliding into one another, Kahahawai got out of the car and yelled "Get that damn haole off the car and I'll give him what he's looking for," referring to Agnes Peeples' white husband, Horace Peeples, according to "The Massie Case."

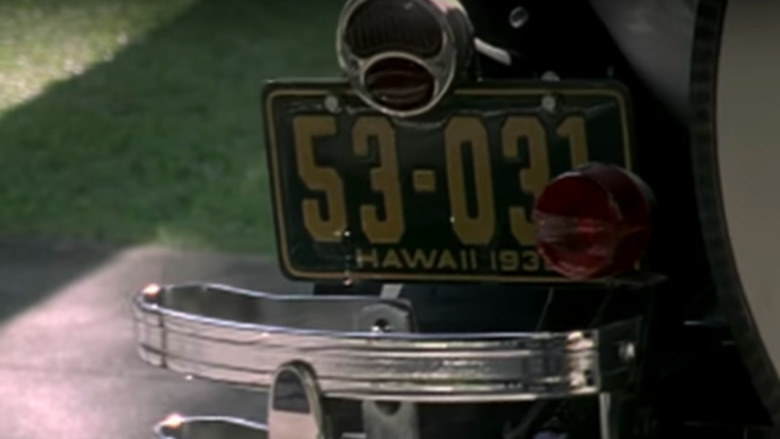

Agnes also got out of the car and shoved Kahahawai, who responded by striking her on the side of her face. Agnes in turn hit Kahahawai and after a brief physical altercation with Kahahawai, she wrote down their license plate number, 58-895, as they drove away. The Peeples went to a police station and after reporting the incident, it was broadcast across the police radios.

According to the Honolulu Civil Beat, some believe that Thalia Massie may have heard the license plate number while police officers were driving her to the hospital to be examined. Ultimately, the Pinkerton Report would show that Thalia Massie was exposed to the license plate number numerous times before she offered her own version.

Another police interview

At 2:35 in the morning on September 13th, Thalia Massie was examined by Dr. David Liu at the hospital. The medical examination determined that although they could neither confirm nor deny that a rape had occurred, Massie did indeed have a broken jaw, which ended up requiring surgery several days later. Meanwhile, Massie reiterated her story to the doctor and nurse that she couldn't recognize her attackers.

According to "The Massie Case," after being examined at the hospital, Massie was once more interviewed by police, this time by John McIntosh, Inspector of Detectives, at the station. This time, Massie was able to recall a license plate number, claiming "I think it was 58-805. I would not swear to that being correct. I just caught a fleeting glimpse of it as they drove away."

Not only was Thalia Massie suddenly able to come up with an entire license plate number, but this license number differed from the car in the Peeples' incident by only one digit. It was also during this interview that Massie said that the name "Joe" came up during the assault, in addition to the name "Bull."

Applying causation to correlation

In the early hours of September 13th, Horace Ida was arrested and brought into the police station around 3:30 AM, since the car he'd been driving belonged to his sister. At that moment, Ida didn't think much of it and admitted to the fact that one of the people who'd been in his car had assaulted Agnes Peeples. But police were determined to connect the two incidents and even brought Ida into a room with Thalia Massie and exclaimed "Now look at your beautiful work," according to Famous Trials. Ida was even told of Massie's assault upon being brought into police headquarters.

According to "The Massie Case," Massie positively identified Ida, although this occurred under circumstances "which might reasonably be calculated to induce hasty, premature opinion and likely to produce false identification." But believing that the police were only interested in him and his friends in relation to the Peeples incident, Ida told police who else had been in the car with him.

Later that day, Kahahawai, Chang, Ida, and Takai were brought by the police to Massie's house for her to identify them. Ahakuelo was brought to her at the hospital for a positive identification. During this time, police also brought the car that Ida was driving to Massie, and although she couldn't positively identify it as her attackers' car at the time, she later testified that the car was "just like the car she had seen the night before."

The media makes up its mind

The two largest newspapers in Hawaii quickly described the young men as "fiends," "thugs," and "gangsters." While Thalia Massie wasn't initially identified by name, the papers wrote how the assault had occurred to "a refined and cultured young lady 'of the highest character,'" per Famous Trials.

And although Massie described her accusers as "Hawaiian," the five young men came from various ethnic backgrounds. Two were native Hawaiians, two were Japanese, and one was Chinese-Hawaiian. However, as noted in "Bridging Divides in Divisive Times," the men "were monolithically cast as 'Hawaiians' by not only their accuser but also the white population at large." According to "The Massie Case," "the mainland press and the mainstream, white-owned Hawaiian press was quick to frame the rape within the narrative of racialized moral panic where the integrity of white morality was being threatened by perverse sexual proclivities of the native population."

Many of the papers, in addition to printing the boys' photos and addresses, also underlined prior charges that Ahakuelo and Chang had faced. Ahakuelo, Chang, and several other boys had faced a charge of gang rape before, but during the trial the girl who made the accusation admitted that she'd only claimed that it was rape after being sex-shamed by her mother and her aunt. Despite this, the jury gave a guilty verdict "to send a message that such immoral behavior by Honolulu's youth would not be tolerated."

Territory of Hawaii v. Ben Ahakuelo, et al.

On November 16th, 1931, the trial against Kahahawai, Ahakuelo, Ida, Takai, and Chang began. However, the prosecution's case had a glaring weakness that became apparent throughout the trial: there wasn't much time in which the rape could have occurred.

According to Famous Trials, Thalia Massie was last seen with a white man on John Ena Road around midnight on September 13th and wouldn't be picked up by the Bellingers and the Clarks until 12:50 AM. Meanwhile, Kahahawai and the others were seen by witnesses along Beretania Street around 12:15-12:20 AM, "a substantial distance from the site of the alleged rape," and around 12:35 AM, they were involved in the near collision with the Peeples. Considering the fact that the altercation with the Peeples happened roughly a 10-minute drive away from the site of the alleged gang rape, there would have been little-to-no time for a gang rape to have been committed by Kahahawai and the others.

"The Massie Case" explains that the defense accused both the police and the prosecution of framing the defendants, and they didn't dispute the claim that Massie had been raped. They did this primarily because they feared a backlash if they were too tough with her, but it was also clear from her injuries that something did happen that night.

The trial lasted one month and after the jury was hung after four days of deliberations, a mistrial was declared on December 6th, 1931.

Grace Fortescue seeks vengeance

Despite the fact that no evidence tied any of the five accused men "to any crime involving Thalia Massie," headlines after the decision read "The Shame of Honolulu." Rumors also began to circulate about Thalia Massie's reputation, with one claiming that Tommy Massie had been the one to beat Thalia after he found her having sex with a fellow Navy officer. According to "The Massie Case," Tommy Massie was advised by a doctor to leave Hawaii, but "Tommy insisted on staying so he could clear his wife's name."

Thalia Massie's mother, Grace Fortescue, was furious about the rumors as well as the mistrial. After Fortescue was unable to convince the judge to keep the accused men in jail until a retrial, she convinced an admiral to ask the acting governor instead, but each time they were told that without new evidence, it would be almost impossible to convict. As Tommy Massie and Fortescue tried to come up with a way to make sure that the next trial would end in conviction, Tommy was told that Horace Ida had confessed after being kidnapped and beaten.

The kidnapping of Horace Ida

On December 12th, 1931, Horace Ida was kidnapped by a group of Navy men outside of a speakeasy. Ida was taken to a cliffside where, according to the Honolulu Civil Beat, the Navy men "threatened to throw him over the cliff unless he confessed." When Ida refused, he was taken to a back road in Kailua where he was severely beaten with guns and belt buckles in an attempt to force a confession. After being left for dead, Ida was discovered by a passing motorist, and when he was brought to the police station, it was said that he was "lucky to be alive."

"Honor Killing" explains that Grace Fortescue played bridge with Albert O. "Deacon" Jones, who was part of the group who'd kidnapped Ida, and during one of their games Jones claimed that during the beating Ida had confessed to being one of the rapists. However, he informed them that such a confession wouldn't stand up in court, and they had all been told that without any new evidence, a confession would be the only way to get a conviction.

The murder of Joe Kahahawai

Grace Fortescue and Tommy Massie came up with a plan to kidnap Joe Kahahawai and force a confession in writing, though supposedly they originally planned on only using the threat of violence to coerce him, since any evidence of assault would invalidate the confession. In addition to Deacon Jones, they also recruited Edward Lord, another sailor, for their kidnapping plot.

Famous Trials writes that since Kahahawai was required by court order to meet with his probation officer every morning in downtown Honolulu, Fortescue and Massie knew exactly where to find him. However, "The Massie Case," notes that Kahahawai was likely "targeted because he was the darkest colored of the rape suspects."

On January 7th, 1932, Jones grabbed Kahahawai as he was leaving the judiciary building and after waving a fake military summons in his face, they ordered him into a car at gunpoint. After taking Kahahawai to Fortescue's house, the Honolulu Civil Beat reports that Kahahawai was shot in the chest after refusing to confess. In 1966, Jones admitted that he murdered Kahahawai because he "had no use for him."

While trying to dispose of the body, Fortescue, Massie, Jones, and Lord were pulled over and arrested. Since a friend of Kahahawai had witnessed the abduction and reported it, police were already on the lookout for a suspicious vehicle when they discovered the trio with Kahahawai's body.

If you or a loved one has experienced a hate crime, contact the VictimConnect Hotline by phone at 1-855-4-VICTIM or by chat for more information or assistance in locating services to help. If you or a loved one are in immediate danger, call 911.

Territory of Hawaii v. Grace Fortescue, et al.

Initially, a grand jury kept voting not to indict anyone for the murder of Joe Kahahawai, but the judge refused to accept this, giving the grand jury "a legal sermon about their duties." After a couple of weeks, the four defendants were indicted for murder in the second degree. According to the Honolulu Civil Beat, instead of being kept in jail, the Navy successfully argued for the murder suspects to be allowed to stay on the USS Alton, where "they were hailed by their friends as heroes."

Throughout the trial, one of the defense attorneys, Clarence Darrow, described the murder as an honor killing, which is how many white people considered the murder at the time. Meanwhile, an NAACP report said "The only lynching recorded thus far in 1932 by the NAACP is that of Joseph Kahahawai of Hawaii, on January 8th."

Although all four were all found guilty of manslaughter, their 10-year sentence of hard labor was commuted by the territorial governor of Hawaii to one hour, to be served in his office at Iolani Palace. This was done in an attempt to avoid imposing martial law since the white community was indignant even before the sentencing.

Meanwhile, the governor decided to amend Hawaii's rape statue. "The need to corroborate a female victim's allegations" was eliminated while new language was added to allow for capital punishment in rape cases. Twenty-one days after Joe Kahahawai's murder, the amendments were signed into law.

The Richardson Report

Four days after Joe Kahahawai was murdered, President Herbert Hoover ordered an investigation. Assistant Attorney General Seth Richardson was sent to Hawaii to make a report. Congress was especially concerned about the incident due to "Hawaii's strategic importance in the Pacific," according to "The Massie Case," but they also wanted to address the rumors of a crime wave and the claim that in the past year alone, hospitals in Honolulu alone had reported at least 40 rapes.

The Richardson Report reported that there wasn't a crime wave in Hawaii, and in fact there was instead "ample evidence of extreme laxity in the administration of law-enforcement agencies." The 40 alleged rapes were also investigated, and the Richardson Report stated that they "were unable to substantiate it. The hospital records do not indicate any condition. In fact, it was conceded by Captain Pfeiffer, of the Navy police, that such a report had been inadvertently made and could not be substantiated." Despite this, rumors continued to spread across the mainland United States that "white women were often raped on the Islands, with the perpetrators evading justice."

The report also claimed that despite everything, "the races seemed to be still carrying on together with exceedingly little friction," noting that any friction that did exist was simply "due to competition for local women and girls."

The Pinkerton Agency reinvestigates

The Pinkerton National Detective Agency, famous for its anti-labor activity, ended up being responsible for the report that cleared Kahahawai, Ahakuelo, Ida, Takai, and Chang. Hired by the governor since the FBI refused to investigate, the 273-page Pinkerton Report was submitted on October 3rd, 1932.

The Pinkerton Report found that the alibis of the Ala Moana defendants were consistent with witness testimonies and that there was no evidence to support the idea that they were responsible for the rape of Thalia Massie. Ultimately "the Pinkerton Detective Agency did more than any other entity to clear the names of the minority defendants wrongfully accused in the alleged rape of the wife of a navy officer." However, the report also held "an antiquated view of rape," and after questioning why Massie didn't simply resist, for if she had resisted adequately enough there would've been more signs of a struggle, it claimed that Massie hadn't been raped.

According to Famous Trials, four months later, all the rape charges in the Massie case were dropped. At this point, the Massies had already left Hawaii, so chances for a retrial were slim anyway.