Why The Boston Tea Party Really Happened

The Boston Tea Party is, like many events in American history, one of those things that Americans collectively stopped thinking about once there was no longer any need to study it for a pop quiz or a term paper. Still, the general basics of what happened are easy-ish to recall: Something about colonists dressed as Native Americans dumping tea into the harbor and the phrase "taxation without representation" is in there somewhere, too.

In fact, the reasons for the December 16, 1773, act of vandalism and property destruction are varied and deep. There was, of course, the whole matter of "taxation without representation." But in a larger context, the event was one of many examples of the colonists rebelling against British rule in whatever ways were available to them. This event and others like it were merely individual dominoes that fell, one after the other, in the lead-up to the Declaration of Independence, the Revolutionary War, and the United States of America finally being freed from British rule in 1783.

This is why the Boston Tea Party really happened.

Taxes on taxes on taxes

The period of the 1760s and 1770s was rife with tension between the American colonists and their governors across the Atlantic Ocean. As History notes, a particular bone of contention was the French-Indian War of 1763, in which British troops helped defend the colonies from French expansion. Though the British were successful in protecting their colonies, the financial cost to the kingdom was huge, and the government felt that the colonists owed a debt to the crown, literally and figuratively.

To that end, Britain passed the so-called Townsend Acts, which imposed duties on British china, glass, lead, paint, paper, and tea imported to the colonies. According to Robert J. Chaffin's book, "The Townshend Acts Crisis, 1767–1770," another purpose of the Acts was more philosophical: establish the precedent that Britain could tax the colonies.

Many of the colonists, however, didn't see things that way. They complained that it was unfair that they should be taxed without their own representatives in Parliament.

"Taxation without representation is tyranny," Boston politician James Otis famously told his countrymen, according to the book, "Tax Crusaders and the Politics of Direct Democracy."

Spilling the tea

If Parliament was going to make the colonists pay taxes on imported British goods, then the Americans found a rather simple way around that: They didn't buy British goods. This was particularly true when it came to tea: A significant percentage of the tea consumed by the colonists was either smuggled by the Dutch or obtained by colonial merchants. According to History, the British East India Company was left with thousands of pounds of surplus tea just sitting around in London storehouses, and the company facing insolvency.

In the minds of the British Parliament, the Tea Act of 1773 made perfect sense. As Britannica noted, it served several purposes: It raised revenue by taxing the sale of tea to the colonists; it gave the British East India Company a means of unloading unwanted tea that was just sitting around; and of course, it once again drove home the point that Britain retained the right to tax its colonists. Further, unloading the British tea in Boston would undercut Dutch and/or colonial tea operations.

Soon, British ships laden with East India tea began showing up in colonial harbors. Colonists would then harass the ships and the merchants tasked with selling it, usually forcing the ships to turn around and return home with their cargo.

More than just taxation without representation

It's easy to conclude that the colonists rejected the British tea because they didn't want to pay taxes on it and yet not have representation in Parliament. While that was true to a point, the matter was considerably more nuanced than that.

According to the book, "99 Tactics of Successful Tax Resistance Campaigns," legally imported British tea, though taxed, was actually cheaper than smuggled or colonial tea. Still, the Tea Act effectively created a monopoly on British tea in the colonies, a situation patriot Samuel Adams described as "equal to a tax."

Further, the Act was not likely to put both smugglers and colonial tea importers out of business. What's more, according to Bernard Knollenberg's book, "Growth of the American Revolution, 1766-1775," made available via JSTOR, colonists were concerned that if the British Parliament could effectively create a monopoly on tea, it could do so on other imported goods.

These issues would come to a head in Boston on December 16, 1773.

The Massachusetts governor saw things differently than the colonists

While the colonists had harassed other tea-laden British ships and sent them back home, cargo-filled and having failed to collect the duties Parliament expected of them, in Boston, things were different. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson, appointed by Parliament to govern the colony, was not going to brook British ships being harassed and unable to unload their cargo.

According to the book, "The Boston Tea Party" by Benjamin Woods Labaree, made available via JSTOR, when a ship, the Dartmouth, arrived in Boston Harbor laden with British tea, patriots refused to allow the cargo to be unloaded. Hutchinson, however, refused to allow the vessel to return, creating an impasse. Two more ships, the Eleanor and Beaver, also showed up with unwanted tea and were forced to sit in the harbor, unable to leave.

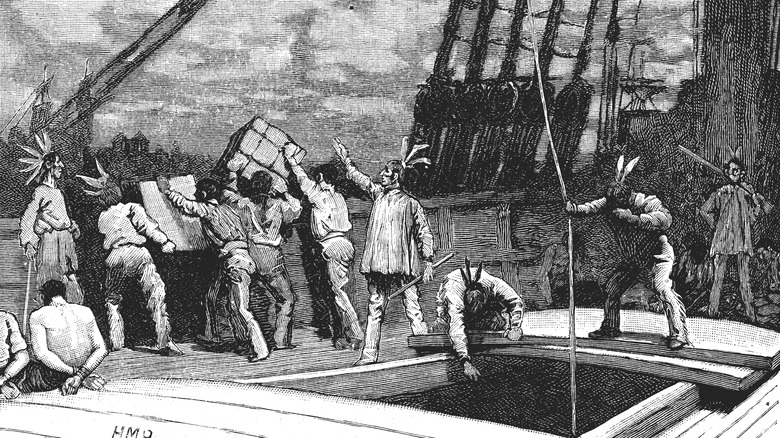

Meanwhile, thousands of patriots, led by Samuel Adams, held a meeting to decide what to do about the impasse. How or why they got there remains unclear two and a half centuries after it happened, but at some point, dozens of men left the meeting, donned Native American costumes, then proceeded to board the ships and throw the precious cargo into the harbor. The rest, as they say, is history, in the most literal possible sense.