Western Period Movies That Got History Totally Wrong

Who doesn't love a good western? It's a little known fact that westerns were the first form of entertainment films, making their debut clear back in the 1890's. In explaining the evolution of the western from then to now, Jourdan Aldredge writes that it was some years after the premier of 1903's iconic "The Great Train Robbery" that the genre evolved to fit "the styles of the times." These days, Hollywood likes pitting the good guys against the bad guys – the cowboys against the Indians, the outlaws against the lawmen and so forth, and the bloodier the better.

The characters' looks have evolved too. Gerald Goll points out that costumers now lean towards the clothing styles of Eastern cities, not the West, shave their cowboys clean, and have just about everyone toting around a gun. In truth too, it was the cowboys whose bathing habits were far lacking when compared to Natives who were often portrayed as dirty but really bathed more often than whites did. Thankfully, film makers are finally getting around to paying homage to the real cowboys of the west, many of whom were actually Spanish or Mexican. So while we can hope for more historically accurate western films in the future, let's take a look at a few that totally missed the wagon train, as it were.

'The Alamo' diverted from the original reason for the battle

In 1835, the Texas Revolution began when American settlers attacked, and conquered, the Alamo in San Antonio, Texas. Just a few months later, 6,000 soldiers under Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna attacked the Alamo and won it back. The 2004 version ignored the first part but focused on the last part, as well as the Texans' eventual victory at the Battle of San Jacinto. But Carla Meyer was just one of many critics to point out the movie "lacks historical context," and made fun of Santa Anna to boot.

There is no word on how descendants of Santa Anna felt about the general being portrayed "as a choleric popinjay of a general who wears a uniform out of a Friml operetta, barks at his subordinates, and preys on young women." And descendants of Davy Crockett, who died at the Alamo, are likely tired of explaining that Crockett never went by "Davy" in his lifetime. The hero's great-great-great-great granddaughter, Joy Bland, explained clear back in 1992 that the name was "just another one of the things that cropped up in the movies.″

Clint Eastwood's 'spaghetti westerns' nearly killed the western genre

To his credit, Clint Eastwood's mysterious man with the chiseled face, narrow eyes, and curling lip has been a staple of the western since he appeared in his first film of the genre back in 1956. In the years since, says The New Yorker, Eastwood has acted in over 50 films and is an established director. But the well-known "Dollars" trilogy – "A Fistful of Dollars" in 1964, "For a Few Dollars More" in 1965, and "The Good, The Bad and The Ugly" in 1966 – propelled the man into the era of the "spaghetti western," the bad films with good intentions that were churned out in Italy and Spain during the 60's and 70's.

Little White Lies submits that while Eastwood's films dispelled the myths of the 1800's in westerns past, they created a few more. His movies also have had a bad habit of making unlikely situations even more squirmy; think "The Beguiled" which deposits our injured, bare-chested hottie-hero in an all-girls school during the Civil War. Even western superhero John Wayne once wrote Eastwood to say he didn't care for "High Plains Drifter" because it didn't accurately portray pioneers of the old west. Eastwood, it is said, did not respond.

'Django Unchained' did not do justice to the issue of slavery

Make no mistake: Director Quentin Tarantino is all about pulpy, gritty movies that can sometimes make you laugh and cringe at the same time. But his "revenge epic," 2012's "Django Unchained," took things a little too far. The movie meant well, pitting an escaped slave and his rescuer against various outlaws to rescue Django's wife from her cruel slave owner circa 1858. But Polite on Society points out the film "is more truly a Spaghetti Western genre" written by a white man who had no idea what enslaved peoples really went through in the 1800's.

The Take, which calls "Django Unchained" a "spaghetti western-blaxploitation-revenge flick" offers that Tarantino's interpretation is certainly not the same as someone like noted historian Ken Burns would be. Also pointed out is the glaring fact that a scene showing two slaves in mortal combat while the owners watch likely never happened, since slaves were deemed valuable property. Internet Movie Database singles out even more goofs, such as the use of belt loops, dynamite, certain words and songs, guns, peanut butter, straws, sunglasses and yes, even Lubbock, Texas – none of which existed until after the 1850's.

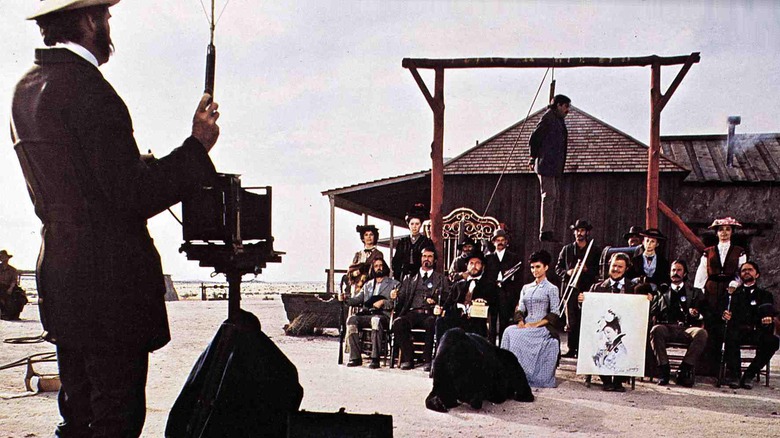

Very little of 'Judge Roy Bean' was rooted in facts

Visit the Judge Roy Bean Visitor Center in Pecos, Texas today and you'll see the original home of this historic character who was already quite colorful when he moved there circa 1881. It is true that Bean was a drunk and yet appointed Justice of the Peace, also that he named his saloon the Jersey Lilly after famed actress Lillie Langtry. But these quirks weren't enough when the 1972 movie about the judge came out, starring Paul Newman. Although a reviewer on Internet Movie Database explains that "Judge Roy Bean" is a comedic love story, there's an awful lot of fiction sprinkled throughout the film.

None of the various shady ladies or outlaws, including "Bad Bob" were real people with the exception of Miss Langtry and John "Grizzly Adams," who actually died over 20 years before the Jersey Lillie opened for business. Also, Desert USA points out that there is no evidence that Bean hanged anyone as he so often did in the film. And critic Roger Ebert accuses the movie of stereotyping its characters, from Bean himself to the beautiful Maria Elena played by Victoria Principal as "the starlet with long black hair, big brown eyes and a freshly scrubbed complexion."

'The Keeping Room' goes too far as a revisionist western

All Movie defines the "revisionist western" as one discarding the stereotypical myths of the "Old West" in favor of giving a more realistic portrayal of how things really happened a century and a half ago. That was the goal of "The Keeping Room" in 2014, wherein three women try to fend off a couple of AWOL soldiers towards the end of the Civil War. In case the audience is unsure of the movie's intention, the very first scene explodes onto the screen with the rape of a woman whose attacker then kills any witnesses who might tell on him.

Perhaps the biggest problem with this movie is that the viewer is constantly reminded that another sexual assault lurks right around the corner. Rather than letting our heroines exhibit any feminist qualities, The MacGuff submits that all the audience gets is "a down and dirty exploitation film masked under artistic tapestries." Writers E. Susan Barber and Charles F. Ritter say that it is true that over 400 women were assaulted during the Civil War, and The Atlantic explains it was extremely difficult to prove it. But that matters little here, since this movie prefers instead for the women to never receive justice, shoot all the men, and traipse from their burning house to an uncertain end. No wonder reviewer Susan Wloszczyna gave it two and a half stars.

'The Last Samurai' has several historical inaccuracies

Although Reader's Digest says that "no American Civil War veteran was present" during the 1877 Satsuma Rebellion in Japan, there was a fellow named Jules Brunet upon whom Tom Cruise's character, Civil War veteran Nathan Algren, was loosely based. But Brunet was French, and his time in Japan was during 1868, not 1877. Screen Rant also points out that "it is still doubtful" that someone like Algren would have even had time to excel to a "master samurai" in the short period of time he was in Japan.

There are more inconsistencies. The character of Saigō Takamori was a real person, and he did die, although not by being shot numerous times by a Gatling gun as he was in the film. Japan Visitor confirms Saigō was actually believed to have completed suicide. Other inaccuracies? Internet Movie Database says that aside from a modern-day telephone pole spotted in the village, General Ōmura Masujirō, who was also portrayed in the movie, died well before 1877. Also that the Japanese hairstyles were incorrect and the Imperial Army never would have used American bugle calls.

'Little Big Man' mainly represents the many myths of the west

"Little Big Man" begins with a very, very, very old Jack Crabb (Dustin Hoffman) telling the story of his life – beginning with being raised by Indians, adopted by a preacher, learning to sling a gun, and unwittingly talking General George Custer into walking right into the fatal attack at Little Bighorn. Crabb covers an awfully big span of the American West's fascinating history while representing just about every stereotype associated with the era. To its credit however, the movie was among the first to view Natives with a degree of sympathy. Most were even portrayed by Native actors, one of the appreciated firsts in the movie industry.

In his 1970 review of the movie, Roger Ebert championed director Arthur Penn's willingness to call attention to the plight of the Natives (they are self-described "Human Beings") while Crabb "touches all the bases of the Western myth." So while Movie Mistakes points out the Wild Bill Hickok was really killed by a 30-year-old man (not a boy as portrayed in the movie) over a month after Custer's Last Stand, it's easy to appreciate "Little Big Man" for retelling some important history in a way that audiences would remember, and appreciate.

'The Revenant': Hugh Glass never talked about surviving a grizzly attack

The biggest draw to this 2015 movie appears to be the grueling and gritty bear attack against mountain man Hugh Glass in 1823, aptly portrayed by Leonardo DiCaprio. But although the Constitutional Whig recounted the story in 1825, Glass himself never spoke about it, leading critics and historians to doubt whether the attack ever took place at all. There are also other problems with the movie. Goliath, for instance says there is no evidence that Glass took a Pawnee wife or had a son by her.

Nor is there evidence that one of the men who aided the mountain man after the bear attack, John Fitzgerald, killed anyone. Buzzfeed verifies that Glass eventually tracked down Fitzgerald and another man, John Bridger, but he did not kill them; the 1825 account says he forgave the men for eventually abandoning him to die. History Net concludes that even the true story was "pieced together" by several accounts by those who knew Glass. That includes a 1939 book by the Federal Writers' Project, "The Oregon Trail," which Time says placed the incident in South Dakota and claimed the grizzly fed parts of Glass's flesh to her cubs as she ripped them from his body. Yuck.

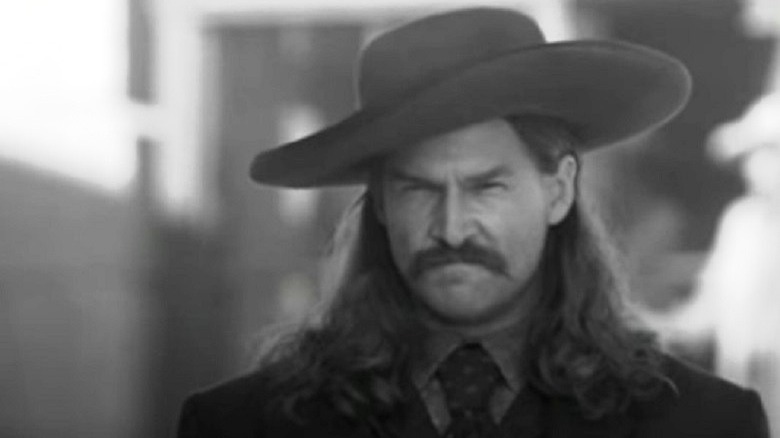

The worst part about 'Wild Bill' incorrectly pairs him with Calamity Jane

From HBO's "Deadwood" to the box office hit "Alien," Walter Hill is a well-known and respected writer/director/producer in Hollywood. But he missed the mark with this version of "Wild Bill" Hickok's story in several ways, including his alleged romance with Calamity Jane. "Wild Bill would have died rather than share a bed with Jane," Hickok's friend Charlie Utter once said. In Hill's version however, Hickok is not only enamored with Jane, but he's also one "mean, high-spirited, but gallant outlaw." He's also supposedly sheriff of Deadwood, which never happened.

In reality, according to Biography, Hickok was involved with a couple of shooting deaths in 1861 and 1865. He also served as sheriff of Abilene, Kansas where he fatally shot his deputy by accident. And Deadwood confirms that Hickok was only in Deadwood for a couple of weeks before being shot to death by Jack McCall during a poker game. Roger Ebert, who rated the film at just two stars, criticized the movie version where Hickok kills some dozen men within the first 10 minutes. And a review on Rotten Tomatoes concluded that "Poor performances and a ridiculous finale made this [movie] a great deception."

'The Wild Bunch' was unnecessarily violent

In 1969's "The Wild Bunch," directed by Sam Peckinpah, a bunch of guys in 1913 ultimately stage a stand-off with Mexican police for "one last job." But previewers hated the film out of the gate, one of them commenting it was "The worst potpourri of vulgarity, violence, sex, and bloodshed I've seen put together." There was another problem too: Legends of America verifies that in the real west, the Wild Bunch was a gang led by William Doolin in 1893. Later, the name was also applied to outlaw Butch Cassidy's gang which happened to be the subjects of "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid," which also came out in 1969. Thus fans expecting to see Doolin or Cassidy on the screen were met with a bunch of fictional, extremely violent characters instead.

Mental Floss says that Warner Bros. successfully released "The Wild Bunch" before the Butch Cassidy movie premiered. To prevent confusion with the latter film, the name "Wild Bunch" was quickly replaced with an alternative name, the "Hole-in-the-Wall Gang." Still, says AV Club, Peckinpah's movie was incredibly violent and vicious, beginning with the opening scene where children drop a scorpion into an anthill to watch it die and leading to the conclusion that "In the end, they're all disgusting insects." And in 1993, the film was still considered so violent that it was re-rated NC-17, not suitable for children.

Films about Wyatt Earp nearly always hail him as a hero

To date, dozens of westerns have paid homage to Wyatt Earp, the lawman/gunfighter who shot it out with bad guys at the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Arizona in 1881. Of two of the most recent films, "Tombstone" in 1993 and "Wyatt Earp" in 1994, Screen Rant gives the award for accuracy to "Tombstone," while the Los Angeles Times votes for "Wyatt Earp" but says 1946's "My Darling Clementine" is "probably the most true to life." The problem is that none of these pictures, nor others about Earp, tell the whole story of this legend whose heroic deeds were, well, not so much.

Let us start out with writer Stuart Lake, with whom HistoryNet says Earp shared his life story. But Earp's "wife," Josephine Marcus, played a heavy hand in the writing of the book to portray her man in the best light possible, especially since it was published after his death in 1929. In truth, reveals the Daily Beast, Earp was accused of a bevy of scams, horse theft, shoddy law enforcement and other crimes both before and after he set foot in Tombstone. Then there's Earp's heavy involvement with the sex work industry in Kansas, says True West, wherein Earp was arrested in a brothel in 1872 where his sister-in-law Bessie happened to live as well as his sometime girl, Mattie Blaylock according to author E.C. Meyers. Hmmm.

The 'Young Guns' movies threw history out the window

Let's just start with a line from Charley Bowdre (played by Casey Siemaszko) in "Young Guns," where he advises that "you can't be any geek off the street, gotta be handy with the steel, if you know what I mean, earn your keep." The word "geek," says Columbia Journal Review, wasn't used in the U.S. until 1935. And so it goes for this pair of films ("Young Guns" in 1988 and "Young Guns II" in 1990) which Rotten Tomatoes summarized as having "too much hat and not enough cattle." But the film did have some actors from the famed "Brat Pack," the loosely-formed group of beautiful young actors of the 1980's and 90's who starred in a series of films.

That's probably why the Young Guns duology was recognized by The Guardian as going more for fun than the history they represented. Viewers of the films best follow the advice of the New York Times' Janet Maslin to approach them in a "none-too-serious spirit," and try to spot the cameo of Jon Bon Jovi, who provided soundtracks for both films. And, Robert Ebert commends the acting by Emilio Estevez, Kiefer Sutherland and the rest of the gang for studying their characters in-depth to give "interesting" performances.

'American Outlaws' was accused of being a 'Young Guns' clone

This 2001 film focused on young Jesse James and his gang as they fight to take back their land from an evil railroad baron. Metacritic, which says the movie cost $35 million to make but only netted $13 million on American soil, called the effort "a lazy retelling of the James legacy" and said it was basically a "'Young Guns' clone." And while History Net confirms that James robbed a few banks and trains, the rest of this movie was too fictional to be taken seriously.

Critic Ken Hanke objected to the film's outlaws being heralded as heroes to begin with, comparing them to a "good natured" rock group setting out on its first tour, ribbing each other over who's the best looking while shucking their shirts so the audience can see their bare chests. The real history was thrown out the window in favor of a few explosive scenes when the gang blows up whatever they are robbing. Notable too is that James' inevitable murder by Bob Ford is left out, leaving "a tidy happy ending" instead. Writer Nell Minow, according to Rotten Tomatoes, rightfully concluded that "American Outlaws" was no more than just another "silly western."