Lesser-Known Heroines Of The American Revolution

George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, John Adams — when we think of the American Revolution, it's generally the Founding Fathers who immediately come to mind. Beyond Abigail Adams, however, who were the women who helped in ways most people don't know about?

Most major conflicts have had women in the background, standing behind men and ready to help when needed, and the American Revolution was no exception. Wives had to separate from husbands, and mothers from children, throughout the war years. Women worked as nurses, scouts, spies, farmers, and soldiers. Some disguised themselves as men and fought in battles. Two, Margaret Corbin and Deborah Sampson, were even granted pensions from the government for their service, according to Economic History.

During the revolution, women accomplished men's tasks and were sometimes even more successful at them, yet, by and large, they did not get the recognition they deserved for doing more than what was asked of them. Here are several lesser-known heroines of the American Revolution.

Margaret Cochran Corbin: loading cannons during battle

Margaret Corbin took her fallen husband's place loading and firing a cannon in the Battle of Fort Washington, and she was the first woman to receive a military pension from the American government. She may also have been known as Molly Pitcher, though that nickname was used for several women who brought water for the cannons during the Revolution, including Mary Ludwig Hays (via Ducksters).

Corbin was orphaned at five, when Native Americans attacked her family in Pennsylvania, where she was born, writes the National Women's History Museum. She and her brother were raised by an uncle. Margaret married John Corbin at the age of 21, in 1772. Her husband joined the Pennsylvania military three years later, and Corbin went with him, doing laundry and helping to care for ill and wounded soldiers.

Toward the end of 1776, the war was raging in Manhattan. At the Battle of Fort Washington, Margaret Corbin donned men's clothing and participated alongside her husband. When he was killed, she took over his station, firing the cannon with skill. She took a hit to her left side while doing so, leaving her arm unusable for the rest of her life. In 1779, the Continental Congress awarded her a pension for life and a set of clothes to replace those that were damaged by her injuries.

Corbin was discharged from the army in 1783, and in 1926, her remains were reburied at West Point with full military honors.

Lydia Darragh: housewife and spy

Lydia Barrington was born in Ireland in 1729, and she married a family friend, William Darragh, at 24. Shortly afterward, they moved to Philadelphia to be with the large Quaker community that lived there.

Lydia spied on the British in 1777 for George Washington. The British occupied the city starting that September, while Washington and his army moved back to White Marsh in October, per American Revolutionary War. Though most Quakers were neutral, the Darraghs quietly supported the Patriot cause.

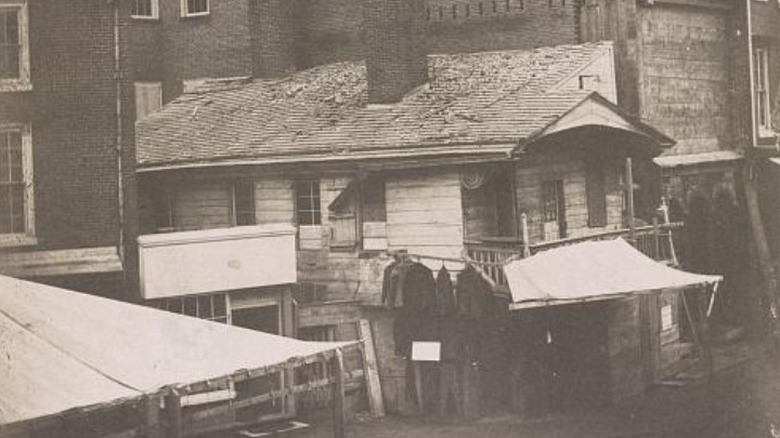

After British troops moved across from and later into her house (pictured), Darragh spied on meetings and was able to warn General Washington about a sudden December attack on his army. Her 14-year-old son John took her coded messages to Lydia's oldest son, Charles, who was with the Second Pennsylvania Regiment (via U.S. History). In the case of the December attack, Darragh warned the Patriots herself by walking to the Rising Sun Tavern on the pretext of filling a flour sack at the mill, according to the National Women's History Museum.

Washington's troops were sufficiently prepared thanks to Lydia Darragh's courage, and the attack led to four days of fighting that ended with a stalemate (via American Revolutionary War), after which the British returned to Philadelphia. After the American Revolution, Lydia Darragh managed a store until her death.

Lucy Flucker Knox: brave hospitality

Lucy Flucker Knox, born in 1756, was one of many wives who followed the army when possible. She was the daughter of a British official, and her family expected her to marry someone in the gentry, according to American Heritage. Instead, she and her husband Henry Knox, a bookseller, married for love when she was 17.

A year later, Lucy and Henry (pictured) snuck away from their Boston home in the dead of night. Their destination? Patriot headquarters in Cambridge. Henry Knox was thought to be a rebel and was therefore not permitted to leave Boston, and Lucy carried her husband's sword, which had been secretly sewn into her cloak.

Over the next two years, the Knoxes were apart more than they were together. Henry was first working on artillery in Roxbury and left Lucy in Worcester with other army wives in the belief that it would be more secure. Lucy and Henry's letters from this time also provide an invaluable portrait of the Revolutionary War for married couples who were forced to separate, writes Mount Vernon.

Lucy Knox joined her husband, by then chief artillery officer, at Valley Forge in 1778 and proved to be very helpful to the soldiers simply by providing good hospitality. She also spent time with Martha Washington. Lucy's determination to join Henry at Valley Forge, as well as her letters, showed her spirit and determination to be more — as well as do more — than what was asked of her.

Margaret Catherine Barry: scouting out the militia

Margaret Catherine "Kate" Barry worked as a scout for the Patriots during the Revolutionary War. She was married at age 15 to Andrew Barry, and they ended up living in Spartanburg County, South Carolina, at a plantation called Walnut Grove. It was on the other side of the Tyger River (pictured) from where she had grown up.

Barry was an accomplished rider and knew the area around her home well, writes The American Revolution. She volunteered her services as a scout for the Patriots in the area when the war started. Several of her family members, including her husband, were revolutionary soldiers. Before the Battle of Cowpens in January 1781, Barry used a shortcut to ride to warn her neighbors that the British were approaching, encouraging them to summon the militia, an effort which increased the number of Patriot soldiers in the battle. Their win eventually succeeded in removing General Cornwallis from South Carolina, writes The Citadel.

There are a handful of other stories about Barry refusing to give up her husband's location, along with that of his troops, to British soldiers. She died in 1823 and was buried at her home (via South Carolina Encyclopedia). Barry's home still stands, now restored, in Spartanburg County (via South Carolina Plantations).

Temperance Wick: hiding the valuables from mutineers

Temperance Wick, aged 22, was living with her elderly parents during the winter of 1780, which was reportedly a difficult one. More than 10,000 American soldiers were camping along the Wicks' 1,400-acre property, and keeping the soldiers properly supplied was difficult for the community. Many soldiers went without shoes, and a mass grave indicates that at least 100 died that winter, according to RevWar Talk. Temperance's father, Henry Wick, died on December 21 of that year.

Around that time, group of Pennsylvania soldiers eventually tired of this and planned a mutiny, and along the way, they stole every horse they could find (via North Jersey's Internet Magazine). Their ultimate plan was to march to Philadelphia to demand their pay. Temperance's mother, Mary Cooper, was ill, and when she rode for Dr. William Leddell, they attempted to take her horse. Later, they searched the property, and Temperance only managed to save her horse because she put him in a bedroom, with bedding on the floor to muffle his hooves (via RevWar Talk). Temperance reportedly kept her horse in the guest bedroom until New Years' Day.

Temperance Wick later married William Tuttle and had five children with him.

Nancy Hart: frontierswoman and spy

Nancy Hart was a frontierswoman who spied on the British for the Patriots. One of her cousins was General Daniel Morgan, according to American Battlefield Trust. She married Benjamin Hart when she was in her 30s, and the family moved to the Broad River area of Georgia in the 1770s.

Hart was around 6 feet tall and imposing; she was so fearsome that local Cherokees called her "Wahatche," or "war woman." Hart would frequently disguise herself as a man and wander through British camps in search of information she could pass to the Patriots, especially as the war moved south.

On one occasion, she even managed to hold several British soldiers captive at her cabin, according to the National Women's History Museum. The soldiers had killed one of her turkeys and expected her to cook it for them. Meanwhile, she devised a plan to get them drunk, take their weapons, and hold them captive. Her plan mostly succeeded, though when Hart was caught holding the last gun, she killed one soldier and injured another. The rest backed off, and when Benjamin Hart returned, he found his wife and daughter with several British captives. Neighbors helped the family hang the men from surrounding trees.

Nancy Hart died in 1803 in Kentucky.

Sybil Ludington: a rainy ride

Sybil Ludington, daughter of Colonel Henry Ludington, made a similar ride to Paul Revere's in New York, at the age of 16, on April 26, 1777. She rode 40 miles in the rain to warn the community of Putnam County that the British were planning to raid the Patriot provisions held in Danbury, Connecticut, according to American Battlefield Trust.

Unlike Paul Revere, Ludington managed to avoid being captured during her ride. The British, meanwhile, were ultimately successful in their Danbury raid. However, notified by Ludington in advance, the Patriots were in place to engage the British close by in Ridgefield, Connecticut, and their militias pushed the British back to Long Island Sound.

Sybil Ludington married a lawyer, Edward Ogden, in 1784, after the American Revolution had ended. She lived until the age of 77 but died in poverty, her petition for a Revolutionary War pension having been denied (via the National Women's History Museum).

Esther Reed: Fundraiser and Activist

Esther DeBert Reed was an activist and civic leader who worked to support the war effort. Though English by birth, she married a lawyer from the colonies and eventually came to understand things from the Patriot point of view, according to Revolutionary War. She authored and published a broadside advocating for patriotism and female support for the war.

Reed recruited 39 other women and formed the Ladies of Philadelphia organization to help raise money for the Continental soldiers. After raising an incredible $300,000, the women used it to buy linen to make shirts for the men on the suggestion of General Washington, since he feared that giving the money to the soldiers would only lead to them spending it on alcohol. The women sewed over 2,200 shirts.

Unfortunately, Reed didn't live to see the end of the war, dying in 1780, after which her work was taken up by Sarah Franklin Bache, Ben Franklin's daughter.

Deborah Sampson: From poverty to pension

Deborah Sampson (also spelled Samson) disguised herself as a man to fight in the American Revolution from May 1782 to October 1783. She was eventually found to be a female and discharged, but she was granted a federal pension for her service, writes Mount Vernon.

Sampson was born into poverty. Her father abandoned the family when she was five, and young Deborah was sent to stay with relatives. At age 10, they could no longer care for her, and she became an indentured servant for the Thomas family in Massachusetts. When she reached 18, she supported herself as a teacher.

In May 1782, Sampson disguised herself as a man and enlisted as "Robert Shurtliff" in the Fourth Massachusetts Regiment. Her regiment then marched to West Point, New York, where Sampson was selected to be part of the Light Infantry Troops. Sampson spent most of her military career in the Lower Hudson River Valley participating in small, dangerous missions. During one mission, she was shot in the shoulder, but, unable to receive medical attention without giving herself away, she continued to work without removing the bullet.

After getting a fever in the summer of 1783, Sampson was discovered to be a woman and was honorably discharged that fall. After she petitioned Congress twice, Sampson was placed on the pension list for disabled veterans due to her shoulder injury.

Patience Wright: sculptor and spy

Patience Wright was a Quaker, sculptor, and spy. When her husband, Joseph, died while she was pregnant with their fourth child, she and her sister put their heads together and started a sculpting business. Though sculpting wax was less highbrow than sculpting metal or stone, it was popular, not to mention cheaper, according to American Battlefield Trust.

Wright would sculpt the heads and hands of her clients in wax, attach them to a metal frame, and dress them in real clothes. Though she moved to England after a fire, Wright did support the Americans' cause and used her wax business to smuggle secret information out to the colonies.

Wright conducted herself like an American while among London society, greeting people of different classes as equals, and was notably immodest for a woman at the time. On top of that, one of her work techniques scandalized many people in London: She would mold the wax under her dress, using her body heat.

Patience Wright organized a group of activists in London who were in favor of the Patriot cause to raise money and uncover information from the British military. She inserted said information into wax figures which were transported to the colonies. Wright herself planned to return to America in 1785 but had a bad fall. She died in 1786, and Congress did not assist with funds for the burial, despite the services she had provided for American independence.

Nanye'hi, aka Nancy Ward: leader and mediator

Cherokee leader Nanye'hi (Anglicanized name: Nancy Ward) was an important mediator between the Cherokee and American colonists. She was born in 1738, around when a smallpox epidemic hit the Cherokee. At the age of 17, she was married with two children. Her husband was killed in battle against the Creeks in 1755 as Nanye'hi fought by his side. After he was struck down, Nanye'hi ultimately led the charge that brought about a Cherokee victory, according to Tennessee Encyclopedia.

She was thus chosen as "Beloved Woman" of the tribe, which meant her words carried more weight in tribal government. She led the Women's Council and had authority over prisoners. Nanye'hi married Bryant Ward, an English trader, in the 1750s. Bryant already had a wife back home in South Carolina, but this was not considered an issue among the Cherokee. He eventually moved back to live with his first wife.

Settlers in the surrounding area grew to respect Nanye'hi as well. Per Britannica, during the American Revolution, she warned founding father of Tennessee John Sevier of a Native American attack. She also had the authority to save white settlers, such as Lydia Bean, who was going to be burned at the stake by Toqua warriors (via Tennessee Encyclopedia).

After the revolution, Nanye'hi advocated for the use of farming and dairy and even became a cattle owner herself. She attempted to persuade the Cherokee not to sell their land so easily, to no avail (via Britannica). She eventually started an inn in Tennessee and died there in 1822.

Mercy Otis Warren: political academic

Mercy Otis Warren was the leading female academic of the Revolutionary War period. She also wrote poetry and was a political playwright. Born the third child of 13 to a prosperous lawyer, Warren would sit in on her brother's lessons to learn. She had no formal education of her own, but she used her family members' libraries to educate herself, writes the National Women's History Museum.

In 1754, Mercy Otis married James Warren, who was quite political himself and encouraged her to write. She kept up a lively correspondence with John Adams, often commenting on politics. Warren also began writing political plays, mainly dramas and satires.

During the American Revolution, Warren kept a written history of the war as it was happening, in addition to writing poetry. She was one of the first American women to publish a nonfiction book (her account of the revolution), and she was the third to publish a book of poems, after Anne Bradstreet and Phyllis Wheatley.

Mercy Otis Warren continued to actively write on her political friends until her death at age 86.