The Tragic True Story Of The 1948 Palestinian Displacement

For many Palestinians, al-Nakba not only refers to the forced expulsion from 1947 to 1949 but evokes the entire history of Palestinian displacement, which is still occurring in 2021. Forced displacement of Palestinians was occurring even during British colonization, and between 1936 and 1939, British authorities destroyed up to 5,000 Palestinian homes.

From its inception, the Zionist project has sought to create a nation through colonialism, made apparent by organizations such as the Palestine Jewish Colonization Association. And as noted by Hadar Cohen, this violence has been committed and continues to be committed in the name of Judaism, despite the fact that for many, "displacing and oppressing others is antithetical to [their] Jewishness."

As of 2021, Palestinian people continue to fight for their right to self-determination and their right to return. Meanwhile, countries like the United States continue to provide billions of dollars of aid to Israel, effectively funding the continued forced displacement of Palestinian people. This is the tragic true story of the 1948 Palestinian displacement.

A brief history of Palestine

Throughout history, the land currently occupied by Israel, also known as Palestine, has seen numerous conquerors, from the Assyrians in 721 B.C. to the Ottoman Empire in 1516 C.E. And according to Palestinian anthropologist Ali Qleibo, "throughout history a great diversity of peoples has moved into Palestine as their homeland: Jebusites, Canaanites, Philistines from Crete, Anatolian and Lydian Greeks, Hebrews, Amorites, Edomites, Nabateans, Arameans, Romans, Arabs ... the various cultures shine for a brief moment before they fade out of official historical and cultural records of Palestine. The people, however, survive."

The Ottoman occupation of Palestine lasted until 1918, one year after British forces entered Palestine, seeking to gain control over the territory as World War I drew to a close. ARIJ writes that although it was believed that Palestine would become an "international zone not under direct French or British colonial control," Palestine ended up remaining under British occupation until 1948. With the Partition Plan, the land was divided by the United Nations, with one part for the Palestinian people and one part for the Zionist state of Israel.

This wasn't the first time that Palestine was treated by Europeans as a place for Jewish people to return to. In 1799, Napoleon offered Palestine to Jewish people who were under France's protection, describing them as "Rightful heirs of Palestine!"

The history of Jewish immigration to Palestine

Following waves of pogroms and anti-Semitic persecution in Eastern Europe starting in 1881, thousands of Jewish people emigrated. While the majority immigrated to the United States, up to 25,000 Jewish people immigrated to Palestine between 1882 and 1884, known as the First Aliyah. The Second Aliyah lasted from 1904 to 1914, and roughly 40,000 Eastern European Jewish people immigrated to Palestine.

According to "Yemenites in Israel," by Nitza Druyan, Yemenite Jews also immigrated to Palestine at the time, and by 1914, "Yemenite Jews were about six percent of the Jewish population in Palestine, while in the Jewish world they were less than one-half of one percent." This occurred partly because "many of the European Jews who set up religious settlements in Palestine gave up after a few months and returned home, often hungry and diseased," reports The New York Times.

Up to World War I, the Jewish communities that were immigrating to Palestine maintained their various ethnic traditions. "Jewish cultural pluralism was part of the pre-Zionist and the pre-State era. Moreover, one's ethnic heritage was recognized as a legitimate expression of Jewish identification in Eretz Israel." However, after World War I, Zionist leaders adopted the position that it was necessary "to create a new image of the Jew as an individual and of the Jewish society as a whole." This involved letting go of the "degenerate lifestyle of the Diaspora."

Zionism and Palestine

Nathan Birnbaum may have coined the term Zionism in 1890, but Theodor Herzl would become known as the founder of the Zionist movement largely due to his work, "Der Judenstaat," or "The Jewish State" (via OpenDemocracy).

Herzl himself questioned "Palestine or Argentina?" and wasn't too attached to the idea of Palestine "until he got involved with eastern European ZIonists, who were attached to the biblical Land of Israel." However, despite the religious connection, the concern was mainly with power, and as a result the Zionist movement "was forced to meticulously sort and thoroughly nationalize some of the religious beliefs in order to turn them into nation-building myths," writes Haaretz.

Palestine wasn't the only option on the map. East Africa was also considered for a temporary Jewish colony, known as the Uganda Scheme, and a settlement was also started in Argentina in 1889. By the outbreak of World War I, Jewish people numbered 6% of the Palestinian population.

Zionists during WWI

Organizations involved in acquiring land in Palestine included the Jewish Colonial Trust, the Jewish National Fund, the Palestine Land Development Company, and the Palestine Jewish Colonization Association (PJCA).

According to "Land, Law, and Legitimacy in Israel and the Occupied Territories," by George E. Bisharat, European Zionists trying to buy land in Palestine appealed to the Ottoman sultan "based on promises that Jewish financial resources would be mobilized globally to lend assistance to his financially strapped empire." Ultimately, "this appeal fell flat," and the Ottoman Empire maintained their restriction on Jewish land purchases and immigration to Palestine. An appeal was also made "to induce the German Emperor to endorse the creation of a Chartered Land Development Company, which would be operation by Zionists in Palestine under German protection," writes Fayez A. Sayegh in Zionist Colonialism in Palestine.

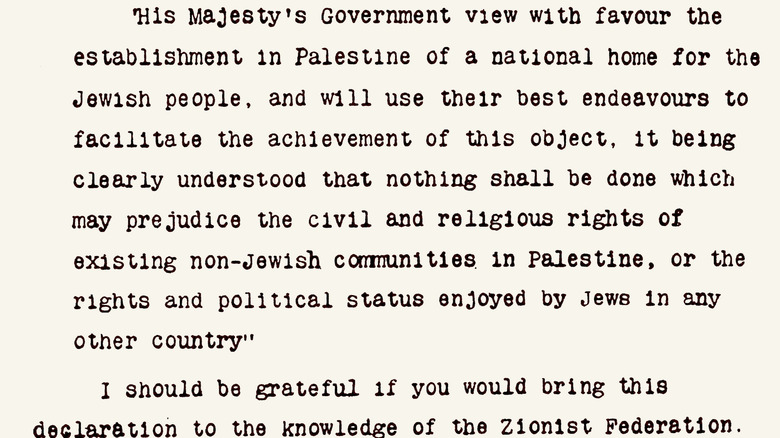

Once Britain took over Palestine, Zionists successfully lobbied the British government into establishing a Jewish 'National Home' in Palestine with the Balfour Declaration.

The 1947 UN Partition Plan

During the beginning of the 20th century, there was a relatively steady stream of Jewish immigration to Palestine. Although the British installed quotas twice, many immigrated through loopholes, and by the end of 1946, Jewish people numbered 32.4% of the population and owned roughly 6% of the land.

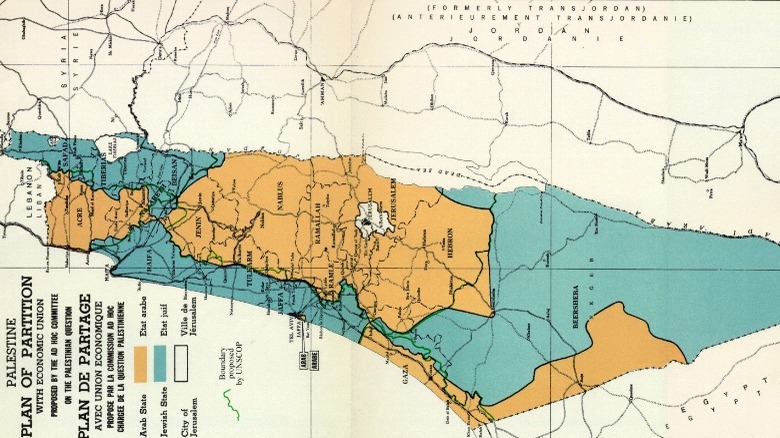

According to Middle East Monitor, on November 29, 1947, the United Nations adopted its Partition Plan for Palestine. And as Fayez A. Sayegh notes in Zionist Colonialism in Palestine, although "enthusiastic support for the proposal came exclusively from Europe, Australasia, and the Western Hemisphere. An alien state was to be planted in the land link between Asia and Africa without the free consent of any neighboring African or Asian country." And while the plan was created in cooperation with the Jewish Agency for Palestine, no Palestinian people were consulted on the plan. The Arab Higher Committee had boycotted the deliberations because the U.N. "had refused to address the question of independence."

Palestinians ultimately rejected the proposal because it planned to give 56.5% of the land to the Zionist state and would have additionally deprived Palestine "of key agricultural lands and seaports." And according to "The Question of Palestine and the United Nations," "the plan was not accepted by the Palestinian Arabs and the Arabs States on the ground that it violated the provisions of the United Nations Charter, which granted people the right to decide their own destiny."

Battling against Zionist paramilitary groups

In response to U.N. Resolution 181, a civil war broke out in Palestine between Palestinians and Zionists. Haganah, Irgun, and LHI were three of the main Zionist paramilitary forces that fought against Palestinians, who had "gained extensive training and arms from fighting alongside Britain in World War II."

British soldier Orde Wingate trained one division of Haganah commanders that became known as "the special night squads," since they trained in the dead of night. Since this group was outside the formal military chain of command, their actions were "wild and uncontrollable," such as one incident that involved forcing villagers to eat sand until they vomited. According to military historian Matthew Hughes, "British SNS brutality prompted Jewish soldiers, taught them how to deal with insurgency and insurgents and set this within a colonial legal framework of collective punishment and punitive action that normalized draconian action."

And although the three Zionist paramilitary organizations had been briefly united against British authority from 1945 to 1946, once the British withdrawal from Palestine was official, they focused their attentions on the Palestinian people and launched a program of ethnic cleansings.

Ultimately, many of the methods used by the later Israeli army, formed out of the Haganah, would mirror those that the British had used against Palestinians in the 1930s, including house demolitions and indefinite internment.

The depopulation of Haifa

By the end of 1947, there were approximately 50,000 Zionist forces fighting against at most 3,000 Palestinian-led guerrillas and 2,000 to 4,000 volunteers of the Arab Liberation Army. And although Plan Dalet, which detailed the depopulation and destruction of Palestinian villages, wasn't confirmed until March 1948, villages were already being targeted by December 1947.

According to Palestinian Journeys, Haganah and Irgun launched random military operations on villages such as al-Tira and al-Abbasiyya on December 12 and 13, respectively, killing and wounding dozens of villagers. The terrorization of Haifa also began in December 1947, leading up to 20,000 of the city's Palestinian residents to seek refuge in Egypt and Lebanon.

Zochrot writes that by February 1948, Haifa became the location of "the first pre-planned, organized expulsion of an Arab community by the Haganah." Inhabitants were ordered to leave, and those who stayed had their houses destroyed — "thirty houses were demolished, and six were spared for lack of explosives." Between 60 and 80 Palestinian people were killed, and those who survived "were driven out."

The first step of Plan Dalet was Operation Nachshon, which involved taking the Tel-Aviv–Jerusalem road, which had been blockaded by the Palestinian militia in February 1948. Ultimately, every Palestinian village along the way was destroyed or taken over, but the village of Deir Yassin is considered to be one of the most notorious massacres of the war.

The Deir Yassin massacre

After ordering the Deir Yassin village inhabitants to leave via a loudspeaker, the Irgun and LHI Zionist forces proceeded to slaughter everyone who remained. According to Middle East Monitor, between 100 to 250 Palestinian people, including children, were murdered over the course of several hours. This despite the fact that Deir Yassin had signed a nonaggression pact with the neighboring Jewish Givat Shaul settlement "and had stuck to it." Ultimately, it was the residents of Givat Shaul who showed up and stopped the slaughter once they heard about it.

Yehuda Feder, who participated in the massacre, wrote how in addition to executing children "against a wall," the village was promptly looted. "We confiscated a lot of money and silver and gold jewelery fell into our hands."

During the pogrom all the village inhabitants were killed or driven out, homes were destroyed with explosives, and after the massacre, the dead bodies were burned. After the massacre, some of the survivors were taken to Jerusalem for a "victory parade."

Despite the fact that the Deir Yassin massacre was well-recorded, many Zionist organizations claim that the Deir Yassin massacre is a fabrication. And as of 2021, the IDF and the Defense Ministry continue to refuse to publish the photographs of the Deir Massacre that it has in its archives.

The 1948 Arab–Israeli War

After the Partition Plan for Palestine had been passed, it was decided that the British mandate over Palestine would end on May 15, 1948. And on the very last day of the mandate, Zionist leaders "called a declaration of independence in Tel Aviv." Because of this, May 15 is considered for Palestinian people a national day of remembrance of al-Nakba, or the "catastrophe."

After Israel declared independence, the neighboring Arab countries joined the Palestinian side of the civil war, leading to what is known as the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. Egyptian, Lebanese, Syrian, Jordanian and Iraqi armies launched an offensive, but despite the intervention, Palestinian displacement only intensified. On June 10 and 11, 50,000 Palestinian civilians were driven out of the towns of Lydda and Ramla, and by May 1949, Dayr al-Qassi and all the villages in its vicinity had been taken over by the Zionist forces.

Just after proposing a second peace plan, Swedish diplomat and U.N. Security Council mediator Folke Bernadotte was assassinated by LHI forces on September 17, 1948. As a result, many LHI forces were arrested, but according to Independent, "if anything, the murder made it easier to integrate most of the Lehi and Irgun forces into the Israeli mainstream." And despite the fact that even the Zionist press condemned the murder, no one was ever "found or brought to trial" for the assassination.

Signing an armistice agreement

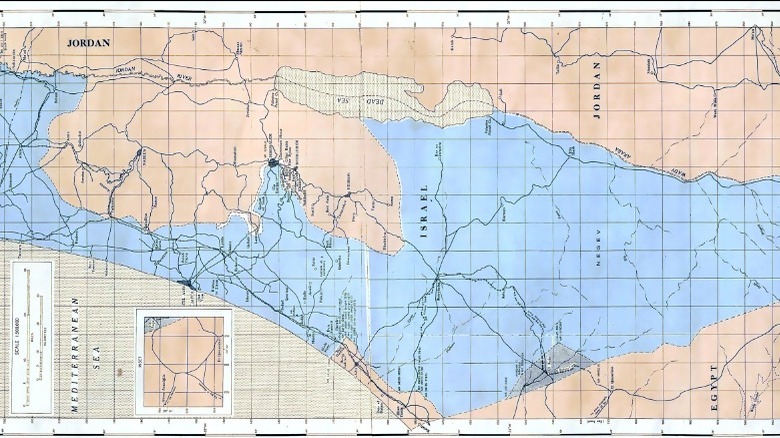

Between February and July 1949, the Arab-Israeli War slowly drew to a close as the various countries signed their own armistice agreements. However, as MDC notes, the agreements were only signed between Israeli and Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria, "without Palestinian involvement and without Iraq, which took part in the fighting but refused to countenance any agreement with the new state of Israel."

Known as the Rhodes Agreements, many Palestinians were angered by the agreements, especially those who found themselves in Israeli territory not because Zionist forces had succeeded in occupying their communities but "as a result of border adjustments made between Israel and Jordan."

The Green Line was also established as the demarcation lines between Palestine and Israel, separating the Gaza Strip and the West Bank as Palestinian territory and giving roughly 78% of historic Palestine to the Zionist Israeli state. As a result of the demarcation lines, Palestine was cut off from the Red Sea as well as the city of Jaffa, "the Palestinian state's major Mediterranean Sea port," and Gaza also "lost its connection to the wheat fields of the Negev."

And according to Al Jazeera, the armistice didn't stop the forced displacements of Palestinians by Zionist forces. In 1950, "2,500 Palestinian residents of the city of Majdal were forced into the Gaza Strip, about 2,000 inhabitants of Beer el-Sabe were expelled to the West Bank, and some 2,000 residents of two northern villages were driven into Syria."

Over 400 villages destroyed

Some 500 Palestinian villages and 11 cities were ethnically cleansed and destroyed by Zionist forces, with some estimates numbering up to 530 villages. +972 writes that the residents of these villages were prevented by Israel from returning to their homes, since the government designated the areas as "closed military zones." If they were allowed, they would find little left of their villages. Most were demolished by Israel, the homes bulldozed or blown up. The majority of villages were totally destroyed, but those that survived ended up being taken over by Israeli settlers.

According to "Remembering the Palestinian Nakba," by Nur Masalha, "the Israeli army and the JNF [Jewish National Fund] became the two Zionist institutions key to ensuring that the Palestinian refugees were unable to return to their lands, through complicity in the destruction of Palestinian villages and homes and their transformation into Jewish settlements, national parks, forests and even car parks. The JNF also planted forests in the depopulated villages to 'conceal' Palestinian existence."

The villages and cities that were taken over also had their names replaced with Hebrew names.

How many were displaced?

Between December 1947 and the first half of 1949, roughly 750,000 Palestinians were forced out of their homes and made refugees. According to Middle East Eye, some fled their villages thinking that they would be able to come back to thresh the wheat. But while some farmers were able "to salvage whatever crops, livestock, or goods they could from their abandoned homes," others were murdered by Zionist militias in the process.

Many were forced to flee from village to village as Zionist militias persisted in their attacks until they ended up in a refugee camp in the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, or one of the neighboring countries. However, according to The New Humanitarian, Jordan was the only country that "granted Palestinian refugees full citizenship rights, except for 120,000 people who originally came from the Gaza Strip." As of 2021, over 1 million Palestinian people remain living in refugee camps.

And in addition to denying Palestinians the right to return, according to Al-Haq, "the 1950 Absentee Property Law became the main legal instrument of dispossession and was used by Israel to confiscate the property of Palestinian refugees and displaced persons."

These forced displacements didn't end in 1949. As of 2021, Sheikh Jarrah is just one of the latest site of Palestinian forced displacement.

How many lost their lives?

During al-Nakba, there were up to 70 massacres and ethnic cleansings against the Palestinian people. And according to Mondoweiss, some of these massacres "took place within the sight of the British police and army; they did not move to stop them."

There were also instances of biological warfare, such as in May 1948, when Zionist forces "injected typhoid in [an] aqueduct" in order to poison the water supply of the city of Acre. There were at least 70 civilian casualties, and "55 casualties among British soldiers."

Upwards of 15,000 Palestinians were killed between 1947 and 1949, the vast majority of whom were civilians. Comparatively, the Zionist side suffered roughly 6,000 casualties, two-thirds of whom were military.

However, the massacres didn't end in 1949, and Palestinians who remained in the West Bank or the Gaza Strip continued to be the subject of ethnic cleansings. These massacres have continued through 2021, as Israeli forces target Palestinian homes with a bombing campaign.

What happened to those that remained?

Palestinians who remained in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip effectively became second-class citizens. During the first 18 years of Israel's existence, Palestinians were subject to a military rule, which has since shifted to a "policy of institutional containment that deals with the Palestinians as a security and demographic threat to the Zionist character of the state and to Jewish majority rule," writes the Institute for Palestine Studies.

According to Haaretz, since 1948 Palestinians have been subjected to political suppression, surveillance, land confiscation, and unfair laws that have created apartheid in Israel. And in 1967, a second Nakba occurred when between 250,000 and 420,000 Palestinians were displaced from their homes. Many were forced to "sign a document declaring that they were leaving voluntarily," writes Orient XXI.

Israeli forces have also continued their program of displacement and ethnic cleansing up through the 21st century. Between 2000 and 2014, 87% of those who lost their lives in the fighting were Palestinian. Between 2018 and 2019, almost 200 Palestinians were killed by Israeli snipers as they protested for Palestinian right to return.

Buildings are also often leveled by air raids with the excuse that they are organizational points for Hamas, a Palestinian Sunni-Islamic fundamentalist organization. While there has been "no evidence to back up the claims," as of May 16, 2021, almost 200 Palestinian people have been killed by Israeli air strikes.