What Really Happened To The Hula Valley?

In the 1950s, the newly formed Zionist state of Israel set out to drain the Hula wetlands. Despite the fact that the Hula Valley was "a massive ecological treasure" where tens of thousands of people lived, it was believed that draining the wetlands could make available more land for farming. So the Palestinians living there were displaced and the Hula wetlands were drained. However, not only was the soil degraded by the draining, but some of it became entirely unusable due to the subsequent effects.

For years, the Hula Valley ended up plagued with dust storms and underground fires as a result of the Hula wetlands being drained. And in the end, the project was so unsuccessful that it had to entirely reverse course.

After roughly 20 years, the draining of the Hula Valley was deemed a mistake and a rehabilitation project began. Since then, the Hula Valley has seen some of the diversity in its flora and fauna return, but many species were forced into extinction because of the drainage. In addition, the tens of thousands of Palestinians who were displaced from the Hula Valley are still unable to return. This is the story of what really happened to the Hula Valley.

Humans and the Hula Valley

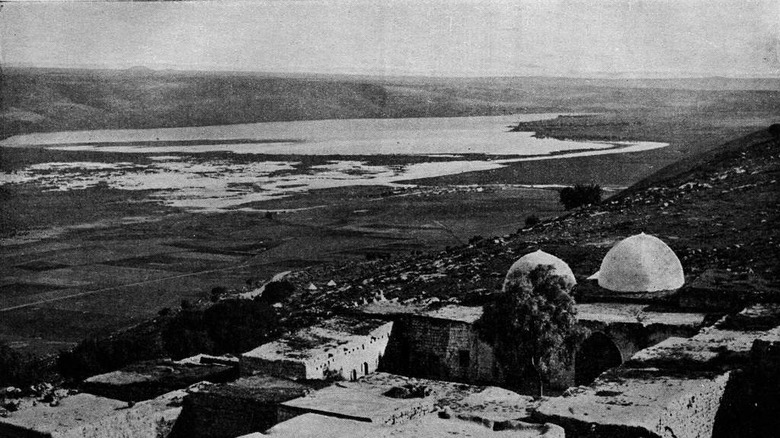

At the northern end of the Jordan River lies the Hula Valley, once the site of Lake Hula, also spelled Huleh. Human presence has been recorded in the Hula Valley dating back tens of thousands of years, and archeologists have found stone tools from 73,000 B.C. Neolithic settlements have also been discovered in the Hula Valley, such as the site of 'Ain Mallaha, also known as Eynan.

According to "Lakes Hula and Agmon," Lake Hula had various names amongst different cultures throughout history. One of the "oldest documented lakes in history," in the 14th century B.C. Lake Hula was called Lake Samchuna by the Ancient Egyptians. By the 1st century C.E., it was called Yam Sumchi in Talmudic literature and Lake Hulata or Ulata in Aramaic. In Arabic, the lake was known as Buheirat el Hule, while in Hebrew it was called Agam Hula.

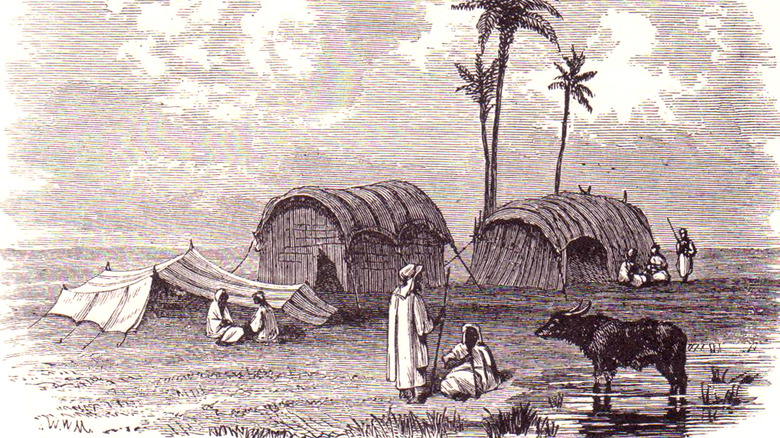

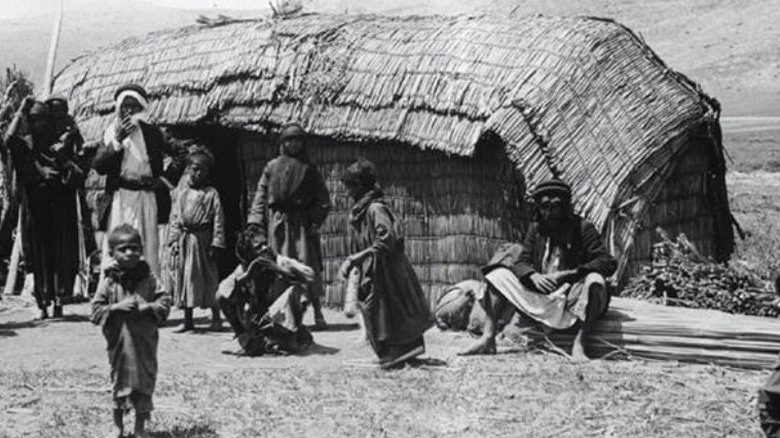

In addition to agriculture, harvesting things such as emmer and barley, the Hula Valley was used as pasturelands for cattle raising. Water buffalo are also thought to have been introduced early, and have been recorded in the Hula Valley, mostly around Lake Hula, as early as the 8th century. The lake itself was roughly 3.3 miles long and 2.7 miles wide and "altogether, the lake and swamps covered up to 23 square miles, with large seasonal and interannual variations in size due to changes in water level."

Before the draining

Before the draining of the Hula Valley and Lake Hula by Zionists in the 1950s, the surrounding lands hosted an abundance of flora and fauna. "Lakes Hula and Agmon" writes that the Hula wetlands were once considered to contain "the richest diversity of aquatic biota in the Levant south of Lake Amiq." Coincidentally, Lake Amiq, also spelled Amik, was drained around the same time period as Lake Hula. The Hula Valley was also once incredibly important as a feeding point for birds that were migrating between Europe and Africa, such as the great white pelican. And several birds, including the Western swamphen and the Goliath heron, used the Hula Valley as a wintering area.

During the 19th century, travelers to Palestine wrote that "panthers, leopards, bears, wild boars, wolves, foxes, jackals, hyenas, gazelle, and otters" could all be found in the Hula Valley. People in the valley had also been cultivating rice since the 1st century C.E., and sugar cane and cotton since the 7th century. However, according to "Blind Modernism and Zionist Waterscape," cotton wasn't too important of a crop until the 1860s, when the Ottoman Empire tried to "fill the niche left by the interruption of the American cotton export trade due to the American Civil War."

Although records vary, there were at least 12,000 people living in the Hula Valley in the early 20th century.

Granting concessions

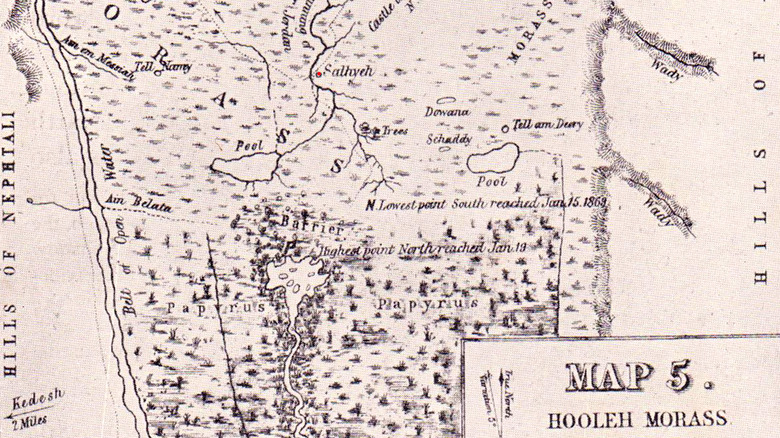

Although the Hula Valley first started being drained in the 1950s, the idea of draining the swamp was being toyed with as early as Ottoman rule. According to "Blind Modernism and Zionist Waterscape" around the end of the 1800s, Sultan Jiftlik, the owner of the land at the time, decided that he wanted to "drain the Huleh swamps in order to make them more productive." The work was contracted to a Turkish engineering firm, which ended up draining "thousands of dunums [worth] of land."

Although the Ottoman government wanted to continue freeing up land for agricultural cultivation and had plans drawn up during the beginning of the 20th century, the British Empire took up the project after they took over what became known as Mandatory Palestine. By this point, the land was owned by a Syrian based agricultural company, who'd acquired the land between 1914 and 1918.

But in 1934, the land was purchased by a Zionist organization known as the Palestine Land Development Company. And within three years, the British Empire was considering "The Huleh Scheme" in the 1937 Palestine Royal Commission Report and figuring out how to assist the "Jewish colonists." "Lakes Hula and Agmon" writes that "the proposed scheme involved digging a canal and diverting the water from above the Hula. By the later years of the British Mandate, it was reported that 'the northern part of the marshes [had] been drained.'"

The official Hula Drainage Project

The main draining of the Hula Valley by the Israeli government occurred between 1951 and 1958. The claimed objectives of the project were eliminating malaria, improving the water supply, and creating more arable land. And "Lakes Hula and Agmon" writes that there was "an additional objective of mining and using peats for fertilizer and for industry," but it was never realized. However, as noted by "Blind Modernism and Zionist Waterscape," by the 1950s, "malaria had already been largely eradicated and many people, Zionists and non-Zionists alike, were correctly warning of the lack of fertility of the peat soil underneath the swamps." In 1953, the Syrian government also protested the draining of the Hula swamp.

But the warnings and protests went unheeded and The Jerusalem Post reports that the draining was undertaken by the Keren Kayemeth LeIsrael – Jewish National Fund (KKL-JNF). The Hula wetlands were drained by widening and deepening the Jordan River while simultaneously constructing canals to divert the water at the north. Perhaps understandably, "the project was, at that time, considered a major national achievement." Susan Abulhawa notes that it was described as "Zionist ingenuity."

By 1958, almost the entirety of the Hula wetlands were drained, creating over 11,000 acres of land for agricultural use. All that was left was a 1.5 square mile patch of the original swamp and lake, which were "enclosed and left inundated and subsequently became Israel's first nature reserve in 1964."

What happened to the Palestinians?

During the 1948 Nakba, tens of thousands of Palestinians were displaced from the Hula Valley by Zionist forces. In "The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem," Benny Morris writes that numerous Palestinian homes were blown up by local Haganah units, creating up to 2,000 refugees during Operation Broom alone: "Operation Broom had a 'tremendous psychological impact' on Safad and the Hula Valley villages, and paved the way for their conquest and the flight of their inhabitants."

In the wake of these attacks, a rumor was spread throughout the Hula Valley that Zionist reinforcements were nearby and that "the time had come to flee. The flight encompassed tens of thousands." But the rumor was only half a lie, and several villages such as Hula, Jish, and Salaha were subject to looting, rape, and massacres. And according to Zochrot, orders were given on the Zionist side not to "allow any Arabs to return to the Hula. Open fire on them all. Return fire in case of attack."

After driving tens of thousands of people out of their homes in order to drain the Hula wetlands, it became clear almost immediately that draining the Hula wetlands was a mistake.

The agricultural problems that arose

There were a lot of issues that emerged as a result of draining the Hula wetlands, but one of the main issues was that the soil of the Hula Valley became unusable for farming. This was pretty ironic considering that this was exactly what the Hula wetlands had been drained for. Since there were large concentrations of peat soil, due to the draining the soil dried, "oxidized quickly and the organic compounds began to disintegrate. The resulting dry soil, now with less organic material, lost its strength to a point where strong winds easily carried the dry soil away and the soil eroded," according to WysInfo.

The fertility of the soil also ended up "declin[ing] sharply." The decomposition produced ammonia, "which increased the release of nitrates and degraded soil productivity," according to "The Hula." And since farmers were unable to make a profit off of the soil, they started abandoning the valley, which ended up contributing to "the rate of soil deterioration," according to "Lakes Hula and Agmon." Jewish Virtual Library notes that "the peat soils proved suitable for agriculture, but the anticipated exceptional yields were never obtained." But according to KKL-JNF, irrigation of peat soil also proved to be problematic: "If it is not sufficiently irrigated it dries and is hard to cultivate, but if it is excessively irrigated the tractors are liable to sink."

Unfortunately, the soil on top wasn't the only problem. There were also the fires underneath.

Underground fires

Due to the drying out and losing volume, the ground level actually ended up falling slightly. As a result, air mixed in with the dried peat soil and "enhanced microbial decomposition of the organic matter." "Lakes Hula and Agmon" writes that this is what caused "uncontrollable underground fires." According to KKL-JNF, these types of underground fires start "when the peat soil oxidizes and emits heat, which is trapped in the subsoil raising its temperature until it exceeds the peat combustion threshold, and spontaneous underground combustion occurs." Plus, in another ironic twist of fate, since these fires burned underground, they could only be put out through flooding. These spontaneous underground fires sometimes burned for a few months on end. And despite numerous efforts to put them out, they were largely unsuccessful.

Due to the dry and burnt soil, in just 35 years, the land ended up sinking almost nine feet, reported New Scientist in 1993. In "Water in the Middle East and in North Africa," Fathi Zereini writes that up to 10% of the total dried area "went through processes causing extreme soil deterioration and subsidence which made it impossible to maintain a beneficial cropping."

And as the soil burned, it turned into "infertile black dust," which caused additional problems of its own.

Dust storms appear

The strong winds that swept through the Hula Valley ended up whipping the black peat soil dust in dust storms that were not only irritating for the local population, but caused "major damage to agricultural crops." In addition, they ended up causing blockages in the drainage canals built in the Hula Valley.

These strong winds also caused extensive surface erosion to the dry soil, but it should be noted that erosion also "increased considerably" due to farming practices such as solely growing cotton as a cash crop.

According to "Long-Term Impacts of Draining a Watershed Wetland on a Downstream Lake," the dust storms were especially severe in the 1970s. There was little done to combat the dust storms, but as the soil became less and less profitable and farmers abandoned them, natural vegetation slowly started coming back: "In the 1980s, these soils were covered by a succession of dense natural vegetation, including phragmites reeds and as a result, the frequency and strength of dust storms declined."

Too many rodents

Another agricultural issue that farmers faced was the unexpected proliferation of rodents. According to "Lakes Hula and Agmon," the population of both voles and field mice skyrocketed and together, they were an absolute menace to farmers and wreaked havoc on all their crops.

The flourishing of the rodents contributed to up to 10% of the Hula Valley becoming "a neglected, uncultivated dry 'desert,'" according to "The Hula," since many farmers abandoned their lands in response to the rodents. By the end of the 1980s, almost 2,000 acres had been completely abandoned by farmers.

Because of the damage that the various rodent populations did to crops, some farmers started using massive amounts of rodenticides in order to kill them off. However, according to the Hydrological Sciences Journal, "the poisoned voles became easy prey for local and migratory raptors, causing secondary-poisoning bird mortality that involved also endangered species." As a result, the entire ecosystem ended up being affected by the rodenticides. In the 21st century, owls have started being used as an alternative to rodenticides.

Ecological problems

The ecological effects of draining the Hula wetlands were manifold. First of all, at least 119 animal species were completely lost from the region in the first 40 years after the draining as were "many freshwater plant species." A number of migratory birds changed their route in order to find an alternative feeding site. In addition to several aquatic invertebrate species that were lost, the Hula painted frog was also thought to be extinct until it was rediscovered in 2011.

The flora and fauna weren't the only things that suffered. The land also felt the consequences of the drainage. According to "Lakes Hula and Agmon," in addition to ammonia, the decomposing peat "released large amounts of nitrates and sulfates that were washed into Lake Kinneret during the winter rainy season." The nitrates and sulfates also ended up being washed into Lake Kinnerat whenever floods were instigated to put out the underground fires.

According to WysInfo, as the soil from the Hula wetlands washed into Lake Kinneret, it led to "an accelerated growth of algae and the reproduction of creatures that fed off them." This led to a "serious reduction in the quality of the water," which was an issue considering the fact that it was the main source of water for much of the surrounding area.

The restoration of the Hula Valley

Despite the fact that the land proved problematic almost from the get-go, it wasn't until the 1980s that people realized that they had to take action to keep the Hula Valley from further deteriorating. But this time, according to "Lakes Hula and Agmon," farming communities donated their land rather than being displaced and seized, and they "stipulated that an alternative means of income from the land must be included in any plan" if they were going to cooperate.

A system of crop rotation was designed, the water table elevation was raised, and Lake Agmon was created by flooding the areas of the Hula Valley that were deemed most unsuitable for farming. The Jordan River was also put back on its original path, and the nitrate-rich water that flowed to Lake Kinneret was captured and used for agriculture. Additional steps were also taken to ensure that the polluted waters don't reach Lake Kinneret.

The rehabilitation of Hula Lake Park

The Hula Nature Reserve is all that remains of the original Hula wetlands, having been allocated in 1964 due to the work of "scientists and nature lovers." But with the rehabilitation and the reflooding of parts of the Hula Valley, the wetlands are slowly beginning to heal themselves.

After having been responsible for draining the Hula wetlands, KKL-JNF took over the restoration project and creation of Hula Lake Park and Lake Agmon. On their website, KKL-JNF notes that they have turned the Hula Valley from "an ecological disaster" into "a great attraction for tourists, with bird watching sites, waterways full of fish, recreational areas in natural surroundings, animals, birds and a great selection of possibilities for outings on bicycles, in vehicles and on foot." In 2009, Hula Lake Park even won international recognition from BBC Wildlife after it was declared "one of the most important observation and photography sites in the world."

Although everything is always in a constant state of flux, the draining of the Hula Valley ultimately proved itself to be unnecessary and it took more time to rehabilitate the Hula Valley than it did to drain it. And while some species were able to return, others became extinct as a result of the draining of the Hula wetlands. Even with the restoration of the Hula wetlands, it wasn't worth what it did to the people, the flora, the fauna, or the land of the region.