John Lennon FBI Files Explained

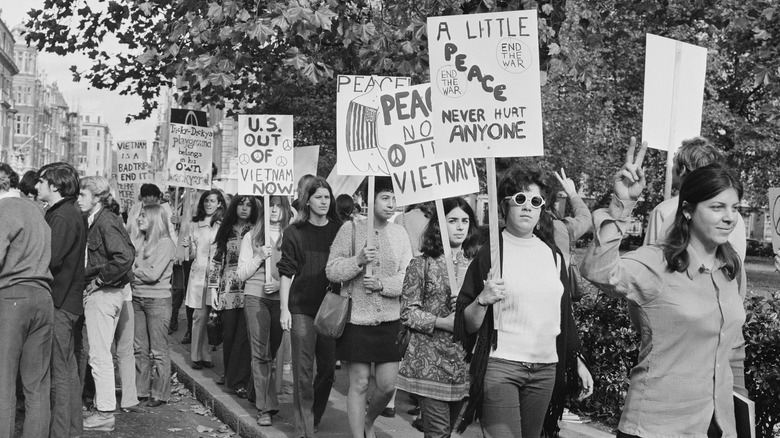

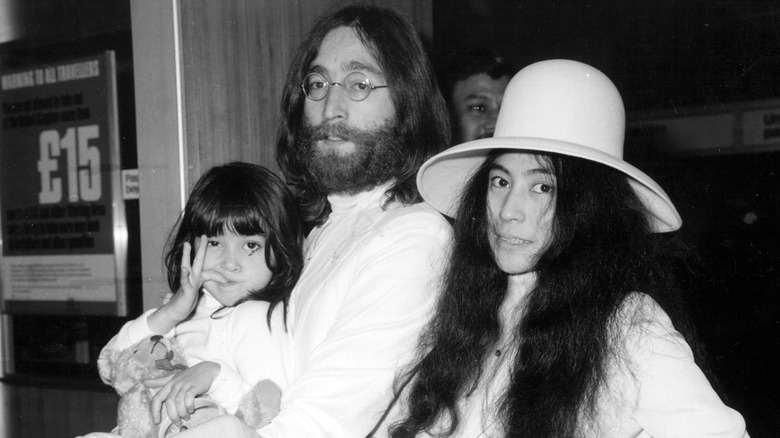

With the Vietnam War still raging and a mass populous of the United States citizenry in an uproar, President Richard Nixon took office in 1969 amid civil chaos. John Lennon and his wife, Yoko Ono, moved to the U.S. in September 1971, where they quickly established a reputation for promoting and throwing their support behind antiwar sentiment.

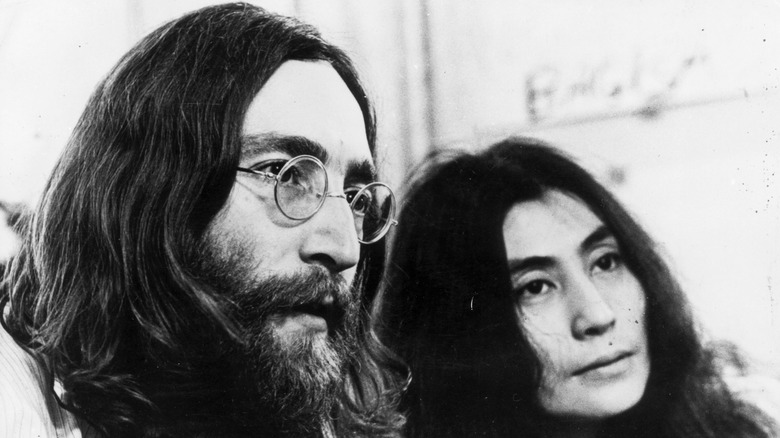

After a brief stint as a New York resident, Lennon was threatened with deportation on a narcotics charge, but it was no secret that the FBI under Nixon was spying on his relationships with Vietnam War activists, as well as his collaborations and charitable donations. While the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover was notorious for surveilling famous activists and celebrities, it was really Nixon who seemed to have a vendetta against the former Beatle, who he deemed a threat to his administration's efforts concerning Vietnam.

Nixon was ultimately unsuccessful in his efforts to deport Lennon, and the FBI ceased surveillance. Two years after Nixon resigned from office in 1976, Lennon was granted permanent U.S. residency. But it was only decades later that the FBI's files on Lennon were released. According to the ACLU, the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California sued the FBI for the release of its files, and the Bureau made public the last 10 documents it had gathered on the international icon in 2006.

So what exactly did the Bureau have on John Lennon and why did they go after him? Here are John Lennon's FBI files explained.

John Lennon's political beginnings

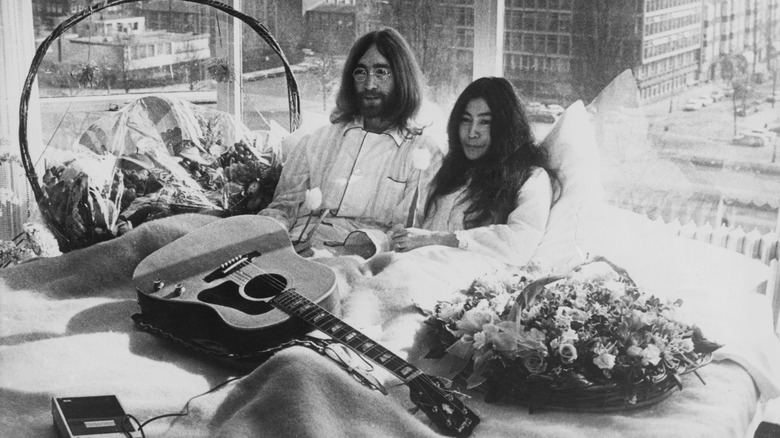

You could say John Lennon officially entered the political sphere during the Summer of Love, 1969, when he and his new wife, Japanese artist Yoko Ono, spent their honeymoon in bed and invited the press to join them. "We knew whatever we did was going to be in the papers. We decided to utilize the space we would occupy anyway, by getting married, with a commercial for peace," Lennon said, according to "The Beatles Anthology."

As expected, their call for world peace made international headlines. They also caught the eye of the American government.

President Richard Nixon had just been inaugurated, and had promised to end the Vietnam War. However, peace negotiations in Paris were slow-moving, and the public continued to put pressure on the U.S. to end the war more quickly. Meanwhile, at their hotel rooms in Amsterdam and in Montreal, Lennon and Ono entertained their own peace negotiations with everyone from rabbis and Hare Krishnas, to conservative media figures.

"In Paris, the Vietnam peace talks have got about as far as sorting out the shape of the table they are going to sit round," Lennon told the press during their "bed-in," via Time. "Those talks have been going on for months. In one week in bed, we achieved a lot more."

Why the FBI wouldn't disclose the files

President Richard Nixon became increasingly concerned that John Lennon would use his influence to complicate the U.S. government's efforts and reputation. At Nixon's request, the FBI began a file on Lennon, which they would later refuse to declassify, claiming that releasing the Lennon files could cause international military retaliation due to Lennon's leftist ties.

It took historian and professor Jon Wiener 14 years to finally convince the Bureau to release the secret documents, according to an extensive NPR radio interview. Wiener later wrote a book, "Gimme Some Truth: The John Lennon FBI Files," about his findings.

"The release of these final documents, concealed from public view for nearly a quarter of a century, reveals government paranoia at a pathological level and an attempt to shield executive branch abuse of civil liberties under rubric of national security," Legal Director of the ACLU of Southern California, Mark Rosenbaum, said soon after the documents were eventually released in 1997.

Why was John Lennon being investigated?

From 1971 to 1972, the FBI tracked John Lennon's activities not only due to his ties with anti-Vietnam War activist leaders, but for his songwriting. As obtuse as it may sound, Nixon and many of his allies were truly afraid that Lennon was preaching radical ideas through his music that could lead to the downfall of America.

When "Give Peace a Chance" was released, it became a protest staple and rallying cry. Lennon began directly associating with certain left-wing activists, and Immigration and Naturalization Services moved to deport him on a bogus past drug charge.

The Nixon administration claimed that Lennon had "been admitted to the country improperly" and that he had "pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor charge of cannabis possession in London in 1968," according to Jon Wiener via the Los Angeles Times. Immigration law at that time banned anyone who had a drug offense on their record from entering the U.S.

Many powerful allies came to Lennon and Yoko Ono's aid, including musician powerhouses like Bob Dylan, movie stars like Tony Curtis, and bestselling authors like John Updike. Still, extradition proceedings ensued until the end of Nixon's Watergate Crisis. Fortunately for Lennon and Ono, Nixon was deported from the White House before he was successful in deporting them.

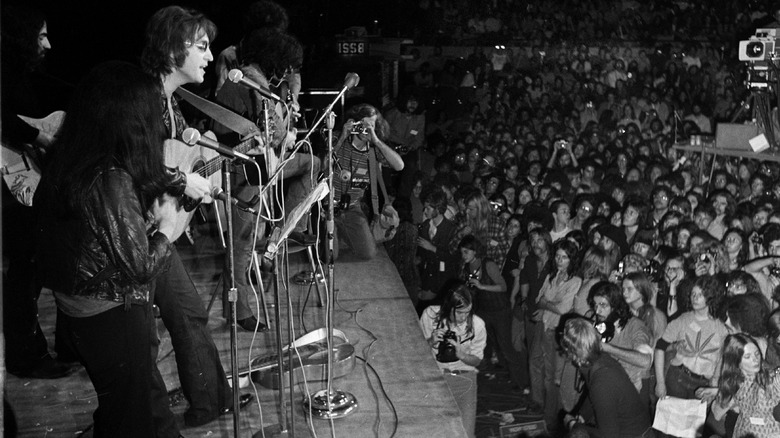

The Free John Sinclair political concert

John Lennon became friends with key Vietnam protesters who were part of the Chicago Seven: Bobby Seale, Abby Hoffman, and Jerry Rubin. The Chicago Seven were a group of anti–Vietnam War protesters who were charged with conspiracy and the intention of inciting riots at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

In 1971, the protestors convinced Lennon and Yoko Ono to headline a political concert/rally to shine a light on writer and poet John Sinclair's arrest for possession of marijuana, and to criticize Nixon's policies. Sinclair was an activist from Detroit who had been part of forming the White Panther Party, a socialist group designed to support the goals of the Black Panther Party in the midst of the civil rights movement.

The Free John Sinclair rally was an eight-hour long show full of political speeches and performances by activists and artists including Allen Ginsberg and Stevie Wonder, according to Ann Arbor District Library, and 15,000 people were in attendance. The event also featured Sinclair himself via phone. Lennon wrote an original song specifically for the concert.

The most important thing to note about that night's events was that its organizers were ultimately successful in their goal: 48 hours after the rally, Sinclair was released from prison, and the Michigan legislature even reformed the state's marijuana laws in order to free him.

The FBI's investigation was at times laughable

Jon Wiener told NPR that he eventually obtained John Lennon's FBI files thanks to the Freedom of Information Act, and he discusses the agents on the investigation's incompetence, referring to them as more "Keystone Cops than the Gestapo."

For example, a Wanted poster of Lennon was produced at some stage, but the photo the FBI used wasn't even his. It was actually an image of David Peel, a folk singer and street performer in the East Village. The photo was from an album cover that Lennon had produced titled "The Pope Smokes Dope." Lennon, who was undoubtedly one of the most recognizable faces in the world at the time, was ultimately mistaken for a local busker. Perhaps it was fortunate for Lennon that the Bureau's investigation was less than sophisticated.

"So the FBI, you know, was lamentably out of touch with the mainstream, not just of... the radical counterculture of New York City, but you would... think John Lennon is kind of pretty much mainstream in 1972," Wiener recollects in the interview.

They even apparently had his address wrong in the beginning of the investigation, claiming he resided at St. Regis Hotel, 150 Bank Street in New York City. It might sound reasonable but the St. Regis is in Central Park, and Bank Street is in the West Village.

John Lennon was wise to the FBI's tactics

Once the threats of deportation began, John Lennon quickly realized they were politically motivated. He publicly spoke about how "too many people were coming to fix his phones," and there were "strange men outside in suits" who he caught following him, according to Jon Wiener's NPR interview. Lennon would eventually sue the FBI for claims of illegal wiretapping.

The FBI collected a lot of nefarious information that could have presumably been used to threaten and intimidate Lennon and Yoko Ono. They knew the whereabouts of Ono's daughter, Kyoko, for example, according to the New York Times.

Unfortunately, when President Richard Nixon was re-elected, the deportation threats continued, and Lennon became more and more paranoid. But documents unearthed years later would prove that he was anything but. Correspondence from Hoover to Nixon's chief of staff confirmed that the White House was directly involved in Lennon's surveillance.

John Lennon and the Communist Party?

There was never any proof that John Lennon was a communist, or a marxist. But that didn't stop the FBI from trying to label him as such. It probably didn't help that Lennon related his song "Imagine" to the Communist Manifesto. The song was released in 1971, at the peak of the FBI's investigation.

"Imagine" became a revelation, and is now a household song. In Rolling Stone, David Fricke writes, "In twenty-two lines of lullaby rhyme, Lennon combined pungent social argument — imagine a world without artificial divisions of faith, politics and greed — with a solace and promise in his voice and piano that could cut through utter gloom."

Now Lennon hadn't just released "Give Peace a Chance" and touted the message "war is over" around a dozen cities during Christmas 1969, but he had released "Imagine," a deeper, more meaningful manifesto of sorts.

"It's not like he thought, 'Oh, this can be an anthem,'" Yoko Ono said. "It was just what John believed — that we are all one country, one world, one people. He wanted to get that idea out."

John Lennon and the Cambodian Prince

Within the FBI's files is a document stating that John Lennon had promised to assist in financing a left-wing bookshop in London. The same document also mentions an appeal that was signed by Lennon and Yoko Ono in support of Cambodian Prince Norodom Sihanouk.

Cambodia was purposefully neutral in the Vietnam War, but was invaded by the U.S. after Vietnamese Communists began using the port of Sihanoukville and Cambodia's eastern border to "ship military supplies on what was known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail," according to the New York Times. The prince turned a blind eye to the U.S. invasion, resulting in his removal by military coup just two years later.

President Richard Nixon defended the action, but it was an incredibly unpopular effort. Not only did a "firestorm of protests" break out, giving the antiwar movement "a new rallying point" for particularly college students, but more than 250 State Department and foreign aid employees signed a letter to the Secretary of State at the time, criticizing the invasion of Cambodia, according to History.

John Lennon and worker's rights

John Lennon was very outspoken about government tyranny and a capitalist system he felt exploited workers, as well as socioeconomic inequality. These beliefs played right into giving the FBI justification for their covert ops.

In 1971, Lennon gave a notably candid interview to Red Mole, which is now Socialist Resistance, in which he told Tariq Ali, "I've always been politically minded... and against the status quo." He also mentioned that he was "very conscious of class" and "class repression." In the interview, which also includes Yoko Ono, the couple discuss world politics, including in Europe and Russia, as well how intellectual revolutionaries like Karl Marx and Vladmir Lenin were able to "to get through to the workers." He also relates his political views back to his song "Working Class Hero."

Lennon's unapologetic, public rhetoric endangered his chances for U.S. citizenship and continued to make him vulnerable to surveillance from the FBI and the Nixon administration.

The Republican National Convention

John Lennon was accused of funding what the FBI coined the Allamuchy Tribe, a protest organization run by a handful of the former Chicago Seven. It turns out that Lennon donated $75,000 with the goal of helping the group form a demonstration against the 1972 Republican National Convention.

People who have analyzed the FBI's actions since have noted that Lennon's antiwar, pro-worker's rights rhetoric had been going on for years, but the FBI investigation began on the cusp of the convention in January 1972, where President Richard Nixon was a favorite to become re-elected. At this time, not only were Lennon and his family put under surveillance, but deportation proceedings also started. The New York Times also notes that once Nixon was re-elected in November of the same year, the FBI closed its investigation on Lennon. Upon closer inspection, it appeared that Nixon's goal was to kick Lennon out of the country before the convention.

During the deportation process, Lennon and his lawyers argued that the action was a directly result of his comments critical of Nixon, and they made appeals that caused significant enough delay to allow him to stay in New York.

The FBI files were pretty fluffy

Ultimately, the FBI couldn't pin John Lennon down on anything concrete. Most of the 300-page documents they created simply involved speaking of Lennon as someone with "revolutionary" and "proletarian'" leanings, and some of his song lyrics were included as examples of his politics, such those from "Power to the People."

The Bureau outsourced informants, paying them to spy on Lennon by attending his concerts and speeches, according to SFGate. This tactic had been used on cultural icons in the past, including Charlie Chaplin and Pablo Picasso. Unfortunately, the FBI's plan to catch Lennon revolved around a mere theory that Lennon and his friends and family were planning a get-out-the-vote concert tour to recruit newly of-age voters. Interestingly, this never happened because of President Richard Nixon's deportation obsession.

The declassified documents suggest a level of unnecessary paranoia by the U.S. government concerning Lennon. In his 1983 suit to retrieve the documents, Jon Wiener was represented by ACLU of Southern California attorney Dan Marmalefsky. According to an ACLU press release, Marmalefsky built his case on the absurdity of it all. "From the beginning the FBI treated John Lennon as if it were a crime to sing 'Give Peace a Chance,'" Marmalefsky said. He also commented that the case reveals "how our government exploits the claim of national security to shield itself from political embarrassment, subverting the First Amendment and the Freedom of Information Act."

The Aftermath

Jon Wiener's book "Gimme Some Truth: The John Lennon FBI Files" was finally published in 2000, after he was able to retrieve and dissect the portion of declassified documents the FBI had released to him. The final 10 files were only released in 2006, the same year that a documentary that specifically focused on John Lennon's war with the U.S. government called "The U.S. vs. John Lennon" was released. It discusses the FBI files at length.

"What distinguished Lennon and Yoko Ono from many of their contemporaries was their ability to capture and make use of the absurdities of their fame," New York Times critic A.O. Scott writes in his review of the documentary. "They come off as canny self-satirists in earnest devotion to the cause, and their combination of humor and guilelessness still has the power to disarm."

The Guardian dubs Lennon as a "brilliant irritant, with a superb line in dumb insolence — and not-so-dumb insolence" who discovered radicalism, but masked it somewhat with performance art-like stunts.

Perhaps this talent of theirs acted as a saving grace during their turbulent experience in early 1970s America. The FBI's bizarre and out-of-touch tactics didn't hurt either.