The Messed Up Truth About The Dred Scott Case

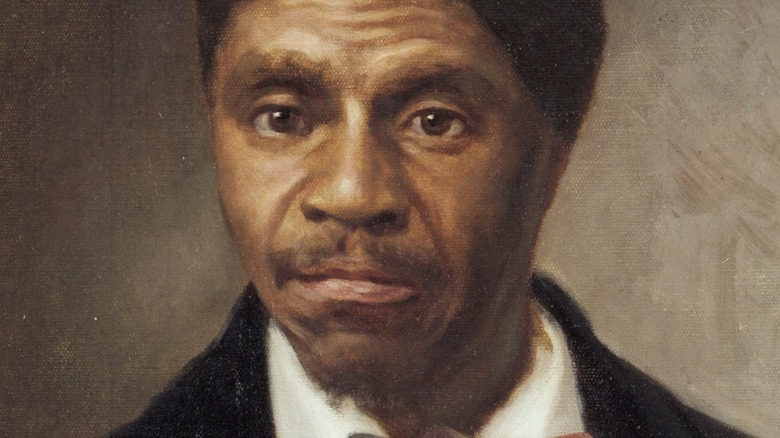

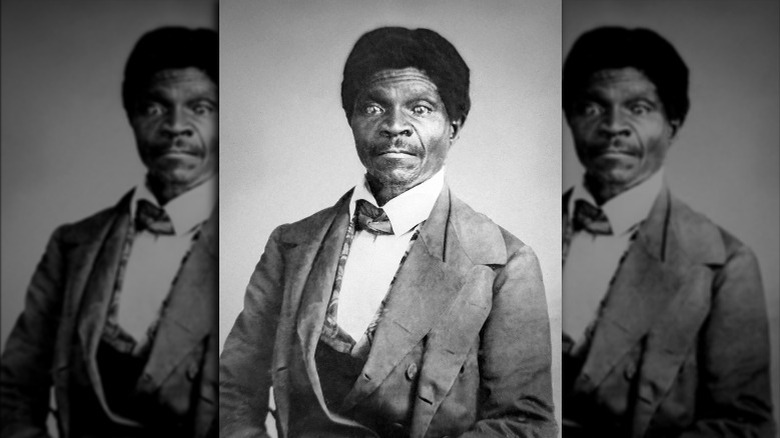

It's safe to say that Dred Scott is someone who most American students have heard of at one point or another before their high school graduation. Yet, though his face was likely featured in your history textbook, how much do you really know about his life and the dramatic Supreme Court case that made him a focus of American politics?

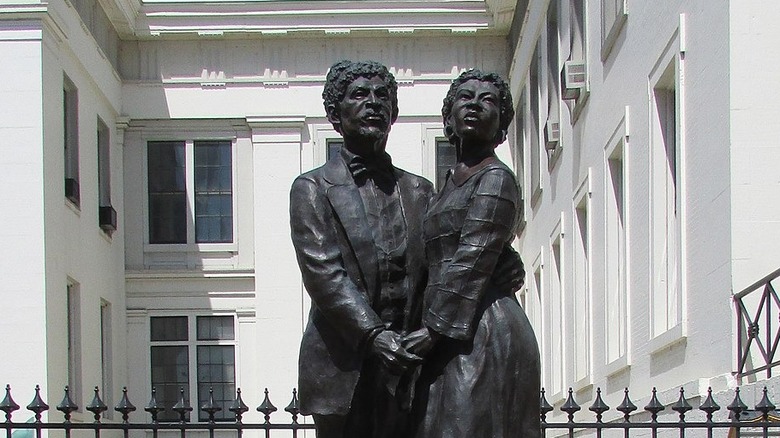

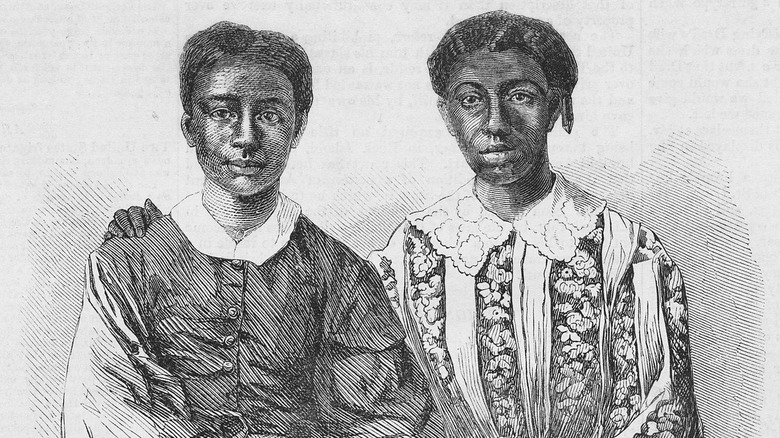

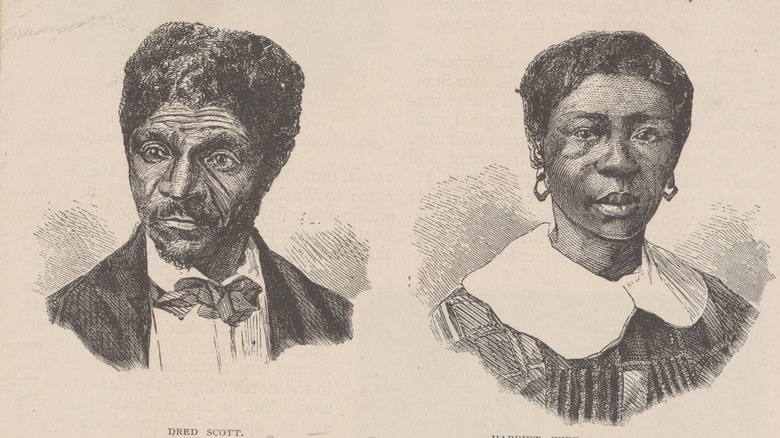

Dred Scott, along with his wife, Harriet, legally sued for his freedom in 1846, according to History. Scott claimed that because he had traveled to states that had outlawed slavery while still a slave himself, he had legal grounds to claim his freedom. The courts and seemingly everyone else, however, sometimes had a different idea. The Scotts' case went from their local Missouri courts and, over the course of a decade, finally made it to the United States Supreme Court in a high profile case watched by seemingly everyone in the country.

Along the way, the matter of slavery was becoming an increasingly divisive topic that threatened to split the nation in two. The 1857 result of Dred Scott v. Sandford in the Supreme Court produced a reaction so dramatic and intense that many believe it was one of the sparks that lit the fires of civil war. And, at the core of it all, was a very real man and his family fighting for their freedom. This is the messed up truth about the Dred Scott case.

Dred Scott was born into slavery

Like so many other enslaved people, the exact details of Dred Scott's early life are vague and hard to uncover. We do know that, according to Biography, he was born sometime around 1795 in Virginia. Though he was born into slavery, it's not clear if the Blow family was the first to claim to own him, though he worked for them fairly early on in his life. An unverified legend has it that Scott's name was originally Sam but, upon the death of an older brother, he took the name Dred in his honor.

Scott would spend a significant portion of his life moving around the country at the behest of his masters, beginning with the Blow family's move to Huntsville, Alabama. As Missouri Digital Heritage reports, family patriarch Peter Blow had attempted to farm there but, upon failing, moved again to St. Louis, Missouri. Scott was apparently obliged to move with them as Blow started running a boarding house. Sometime shortly before or directly after Peter Blow's 1832 death, Scott was then sold to Dr. John Emerson.

Though he was originally a civilian doctor, Emerson would eventually become an assistant surgeon for the U.S. Army, necessitating a move to a posting in Illinois, then largely considered a free state that had outlawed slavery. Given that Emerson took Dred Scott with him, this move would eventually form the bedrock of Scott's later petition for his freedom.

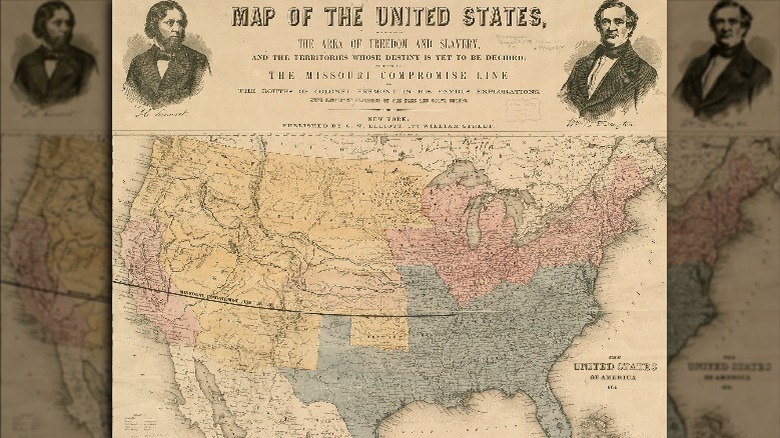

The case was linked to a tenuous national agreement about slavery

After Scott's birth, but well before he and his wife formally argued for their freedom, a national settlement on the matter of slavery created more tension over an issue that had already created deep political and ethical divides.

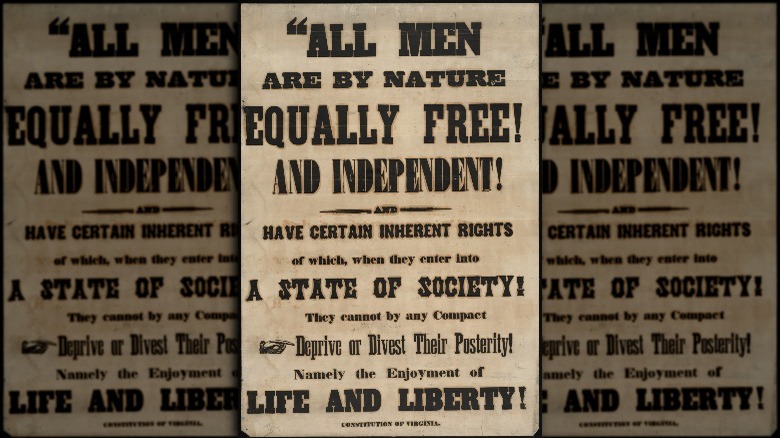

The settlement in question was known as the Missouri Compromise. As the American Battlefield Trust notes, it was linked to the westward expansion of Americans into new territory. But, should those new territories and states allow slavery within their borders? In 1819, Representative James Tallmadge of New York proposed that Missouri, the latest potential state, could only gain statehood if it stopped importing slaves and that all children born to Missouri slaves would then be free.

Congressional politics struck out Tallmadge's plan, but enough members of the House supported the move that something had to be done. As History reports, Speaker of the House Henry Clay came up with what was known as the "Missouri Compromise." Per Clay's plan, Missouri would be admitted as a slave state, but Maine would be a free state to effectively balance it all out. Later adjustments to the plan meant that slavery was banned in all U.S. lands bought via the Louisiana Purchase. The boundary line happened to run just south of Missouri. Naturally, the compromise pleased almost no one and, in 1854, it was repealed by the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Yet, the legacy of the Missouri Compromise was far from over.

Dred Scott was a slave in a free state

Though the Missouri Compromise was a deeply controversial piece of legislation that upset anti-slavery abolitionists, pro-slavery southerners, and everyone in between, it was still very much in effect when Dred Scott moved to the then slave state of Missouri in the 1830s. Things got complicated when Scott moved to Illinois with Dr. John Emerson, given that Illinois was technically a free state, according to History.

A second move to the Wisconsin Territory also meant that Scott found himself in yet another region that had banned slavery, though he was still in servitude himself. At this point, Scott met and married another slave, Harriet Robinson. Harriet's ostensible owner transferred the ownership of Harriet to Emerson, allowing the newlywed Scotts to stay together. They also stayed behind, hired out by Emerson as he went south to Louisiana and eventually got married. The Scotts were recalled to join them in St. Louis in 1842, as the National Park Service reports.

For much of this time, neither Scott nor his wife, Harriet, formally petitioned for their freedom, though they had the legal standing to do so. It's not entirely clear why they kept quiet, though historians have their guesses. It could be that, with two young daughters, Dred and Harriet weren't inclined to cause trouble and risk splitting up their family. They may also have been kept unaware of the Missouri Compromise or how, exactly, they could legally petition for their own freedom.

Dred Scott wasn't just suing for his own freedom

On April 6, 1846, both Dred and Harriet Scott each filed a suit against Irene Emerson, the widow of Dr. John Emerson and the woman who was their ostensible owner at the time. According to Missouri Digital Heritage, the Scotts had apparently been living in St. Louis for much of the time, being hired out to Emerson family members and other people in the community. However, records of their movements are incomplete, even in the later court records that made it all the way to the United States Supreme Court. So, though it's reasonable to assume that Dred Scott and his family largely lived and worked in Missouri in the time before their 1846 filings, it's not entirely clear. The couple were also arguing for the freedom of their two daughters, Eliza and Lizzie.

Why did Dred and Harriet Scott bring their case to court now and not earlier? According to the National Park Service, there are multiple situations that may have led them to file at the time that they did. It could be that Irene Emerson was thinking about selling the Scotts, possibly breaking up their young family in the process. Dred and his wife may have been sick of being hired out to people who were likely strangers to them. It may even be that Dred had earlier attempted to buy his freedom from Emerson, as other slaves had done before, but that he had been denied.

The Scott family received legal help from a surprising source

At the time they filed their suits in 1846, Harriet and Dred Scott were unable to read or write, according to History. Yet, not unlike today, the U.S. court system was complicated and wasn't exactly primed to be accessible for people from all walks of life. This may also explain why the Scotts didn't sue for their family's freedom earlier. If they were unable to read information about the Missouri Compromise or local laws or write to others in the know, they may not have known how, exactly, they could gain their freedom through the court.

But they did eventually bring the matter of their freedom into the Missouri legal system and, eventually, to the national stage. How? In short, to successfully bring their case before a court, the Scotts needed legal help from other people. History reports that these included local St. Louis abolitionists, members of their church, and, perhaps most surprisingly, members of the Blow family. This is the very same Blow family who had previously owned the Scotts. In the interim between when the Blows had sold Dred Scott and when they came back into contact with him, some family members had begun to move towards the anti-slavery cause.

The case went through the court system for over a decade

The original 1846 suits filed at St. Louis' Old Courthouse were only just the beginning in what would prove to be a long and tumultuous road for the Scotts and those who both supported and opposed them. The National Park Service reports that the case was first lost due to a technicality, but this 1847 defeat wasn't sufficient to stop the Scotts. The Missouri Supreme Court allowed them to have a second trial, which resulted in them being granted their freedom by the St. Louis County Circuit Court in 1850. Irene Emerson quickly appealed the decision, sending the trial even higher to the state's Supreme Court.

During this time, the Scott family often moved between legally "enslaved" and "free," their status perpetually uncertain. The Missouri Supreme Court came down firmly on the side of Emerson, declaring the Scotts to once again be her property. Furthermore, the court declared that it wouldn't enforce the rules of free states. Further challenges occurred from there, with some courts even going so far as to say that Scott and his family were not American citizens to begin with, and so didn't have the right to sue in court like their white counterparts. Finally, in 1856, the numerous challenges, appeals, and seemingly unending back-and-forth over the matter made its way to the Supreme Court of the United States.

The Supreme Court ruled against Scott and his family

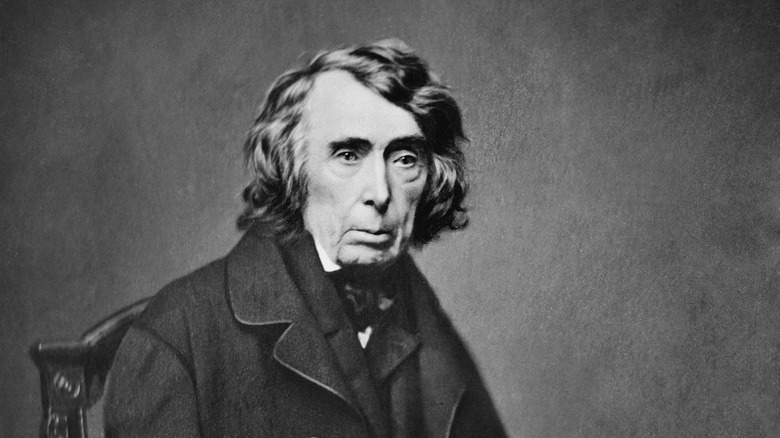

Dred Scott v. Sandford was finally reviewed by the Supreme Court in 1856, though, as the University of Houston relates, the justices did not announce their decision until the following year. Many were shaken to hear that the court had ruled against Scott, going so far as to declare all Black Americans non-citizens and saying that the federal government had no right to free slaves or to make legislation concerning the matter. The court ultimately dismissed the case on this basis, in a 7-2 majority.

Per Oyez, the majority ruling held that, because of the above conditions, a federal court had no business ruling for or against a non-citizen's claim for freedom anyway. The decision not only sought to strip the Scotts of any rights they hoped to have, but also declared the Missouri Compromise invalid.

In the dissenting opinion, Justice Benjamin Robbins Curtis criticized Taney's ruling, saying that if the court had essentially kicked the issue back to lower courts, then what was it doing making such sweeping decisions about the Missouri Compromise? Justice John McClean also chimed in, noting that the decision didn't make complete sense, given that Black men had the right to vote in five states at the time.

Multiple Supreme Court justices were seriously biased

A closer look at the individual justices who ruled in the Dred Scott decision uncovers some potentially serious biases that, at least from a modern perspective, seem to have influenced the 1857 ruling. According to PBS, seven of the nine Supreme Court justices were appointed by presidents who favored slavery, while a further five were from slave-owning families themselves.

However, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney presents one of the more complicated figures in the whole affair. Judging from this case, he appears to be staunchly pro-slavery, to the point where he would deny Scott's citizenship and instead consider him and his family to be another person's property. Yet, as Britannica reports, Taney's personal beliefs present a stark contrast to his actions on the bench. He was devoutly religious, to the point where he believed that slavery was evil and should eventually be done away with entirely. To that end, Taney had even freed his own slaves before he became a Supreme Court justice.

Yet, where many abolitionists of the time wanted to end slavery as soon as possible, it was Taney's position that a gradual change was more appropriate (never mind that real humans like Scott and his family weren't willing to wait for that slow transition).

The case had serious ramifications for slavery and abolitionism in the US

Though the case of Dred Scott v. Sandford had direct consequences for the Scott family and their supporters, it found its place in history largely due to the larger effects it had on the already blazing-hot issue of slavery in the United States. According to Britannica, the Supreme Court's decision effectively invalidated all claims to citizenship for enslaved people, at least on the federal level. It furthermore officially made it so that the issue of slavery couldn't be judged on a federal level, effectively handing the hot potato back to the states.

In the majority opinion, ThoughtCo reports, Chief Justice Taney called the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional. Though the compromise was generally unpopular, its destruction in the wake of Dred Scott's case furthered deepened the divide between pro-slavery and anti-slavery Americans and led to an increased sense of urgency. For many people on both sides of the steadily intensifying slavery debate, it was imperative that the United States had to deal with the issue once and for all.

The Dred Scott case helped stoke the fires of civil war

In the wake of the Supreme Court's decision, abolitionists were incensed. To many, the idea that Black Americans were anything less than full citizens with the same rights as their white neighbors was enough to enrage them. And, though some may have thought that progress was being made inch by inch, the result of Dred Scott v. Sandford must have seemed like a stark wake-up call. Meanwhile, those who supported the institution of slavery celebrated.

And, all the while, the divide between the two groups was growing ever wider and more violent. This was the time of "Bleeding Kansas," after all. Per the American Battlefield Trust, this ongoing conflict from 1855 to 1859 was held between pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions in the territory. It proved to be dramatically violent, to the point where even lawmakers in Washington, D.C. came to blows over the matter — in 1856 South Carolina Representative Preston Brooks beat Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner with a cane on the floor of the Senate, leaving Sumner bleeding and unconscious. The incident rather predictably led to even further polarization on both sides.

This tumult led to Lincoln's nomination as a Republican candidate and his election to the White House, courtesy of anti-slavery northerners, says PBS. Eventually, the growing divide and Lincoln's presence at the seat of government led to the secession of the south from the rest of the nation and the beginning of the American Civil War.

Dred Scott and his family were eventually freed

After the Supreme Court decision, Scott, his wife, and two daughters were considered property again. But Irene Sandford was now Irene Chaffee, having married her second husband, Dr. Calvin Chaffee. And, according to Missouri Digital Heritage, Dr. Chaffee was an abolitionist. He was also pretty unhappy about being associated with one of the most dramatic and controversial cases to make it to the U.S. Supreme Court, not least because commentators couldn't help but notice that he was both an abolitionist and the newest owner of Dred Scott. So, shortly after the Supreme Court handed down its non-decision, Chaffee leaned on his wife to free the Scott family.

The Chaffees quickly transferred ownership of the Scotts to Taylor Blow of the St. Louis Blow family, who had previously owned Dred Scott decades ago. According to Britannica, Missouri state law at the time had made it so that only state residents could free slaves there. Taylor Blow quickly freed them and the St. Louis Circuit Court made it official on May 26, 1857.

As a free man, Scott found work as a hotel porter. Then, in September 1858, he died of tuberculosis. Harriet lived until June 1876, though the Civil War, the Emancipation Proclamation, and the 13th and 14th Amendments (which abolished slavery and gave citizenship rights to all people born in the United States, respectively). And, according to the News Tribune, their descendants still live in the St. Louis area to this day.