The Controversial History Of The United Daughters Of The Confederacy

If you've been taught stuff about the Civil War, there's a pretty decent chance you've heard the argument "it was about states' rights" or something of the sort, right? Well, here's the context in case you're confused. Slavery was a central point when it came to the Civil War. Its continued existence in the South and the potential for it to spread into the western territories rubbed up against abolitionist views, and so the question of slavery — only made worse by other events at the time — led to the outbreak of war. The Emancipation Proclamation just further supported the idea that this was a war fought specifically over slavery, not states' rights.

Nevertheless, this whole "it's about states' rights" thing has persisted long after the end of the Civil War, and there are plenty of Southern monuments you can visit to hear that secession, not slavery, was the cause of the war, or that slavery wasn't really even all that bad (among other things).

As for why these views have stuck around? Confederate heritage associations, mostly. These neo-Confederate groups are pretty universally racist and white supremacist, pushing their own narrative of the Civil War to paint the South in a more positive light. The United Daughters of the Confederacy is just one of those groups, and one which has played a big part in keeping all of those old ideas alive.

The founding of the United Daughters of the Confederacy

Honestly, with a name like "The United Daughters of the Confederacy," it's really not all that hard to imagine why in the world this group would be at the center of some pretty controversial stuff. But let's start smaller, and a little less controversial — the beginning is as good of a place as any.

Per the group's own website, the General Organization of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (or, the UDC) was first founded in Nashville, Tennessee on September 10, 1894, and it also claims that it's the oldest patriotic lineage in the entirety of the U.S. That claim doesn't actually come directly from its 1894 founding, though, but rather from its associations with the Daughters of the Confederacy based in Missouri, and the Ladies Auxiliary of the Confederate Soldier's Home from Tennessee. Both of those trace their roots back to around 1890.

By 1894, the National Association of the Daughters of the Confederacy (named after the "Daughter of the Confederacy" Winnie Davis, pictured above) had its first meeting, headed up by its founder Caroline Meriwether Goodlett and cofounder Anna Davenport Raines. It drew from women's groups like hospital associations and sewing societies that had supplied Confederate soldiers during the Civil War. It's name would be changed to the more familiar United Daughters of the Confederacy by the next year, and the group would be officially incorporated under Washington, D.C.'s laws in July 1919.

What did the United Daughters of the Confederacy plan to do?

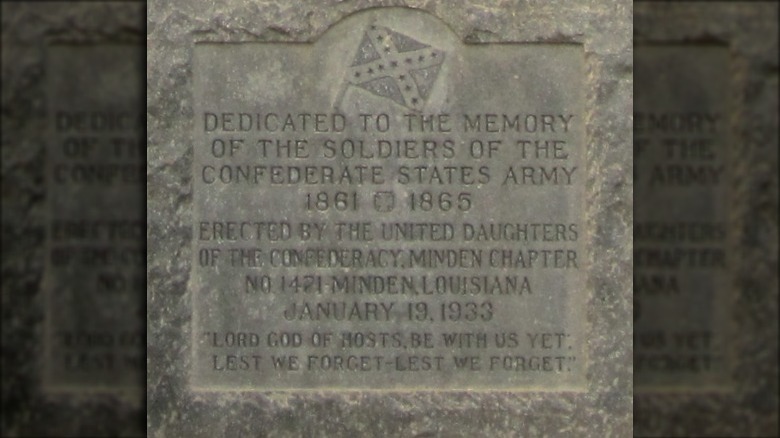

Given the overall size and scope that this organization would end up having over the years, it only makes sense that the United Daughters of the Confederacy went into everything with a plan. Per the UDC website, the organization was founded with the purpose of memorializing Confederate soldiers who served during the Civil War. It involves showing honor to those soldiers and helping out their descendants, while also memorializing "the places made historic by Confederate valor." Basically, they have a lot to do with various statues and memorials and the like (it's something that they're really heavily involved in, and pretty well known for now).

Another page on their website also lists a bunch of scholarships, awards, and funds that they're behind, most of them intended for people who are working to preserve Confederate history, as they would put it — after all, another of their central goals has to do with telling the "truthful history" of the Civil War (despite all the controversy that particular point would end up bringing them).

And then, of course, since they're specifically a women's organization, they intend to memorialize and recognize the part that Southern women also played during the war, remembering their "patient endurance of hardships and patriotic devotion."

'The Lost Cause'

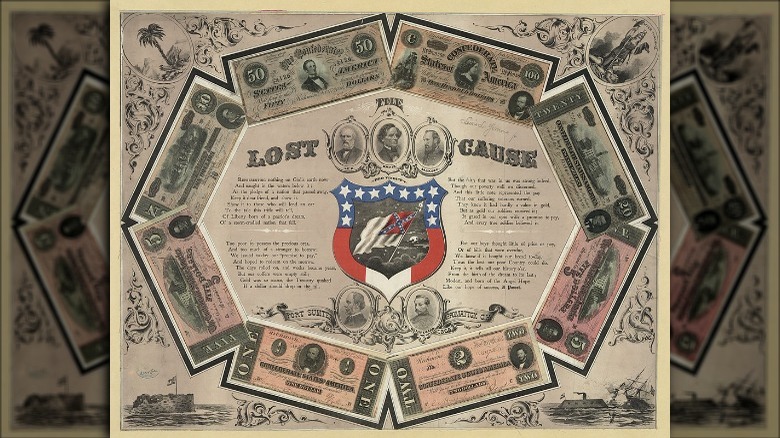

A big part of understanding the United Daughters of the Confederacy and their entire deal also requires a little bit of historical context about what was going on in the South at large, especially in the years following the Civil War. That's where the Lost Cause mythos comes in. According to Facing South, this entire thing was basically a reactionary movement to the events of Reconstruction in the aftermath of the Civil War as a way to reshape the narrative of the conflict.

American Battlefield Trust lays into the details of that mythos, because there are specific points that tend to come up. For one, slavery is taught as anything but the cause for the war. Rather, secession was the cause (and, on top of that, secession was justified as a way to protect states' rights and Southern culture). Plus, apparently, slavery wouldn't have been a valid cause anyway, because the practice was actually humane; slaves were happier when subordinate and weren't ready for freedom. Then, when it came to the war itself, the South was only defeated because of logistical reasons (the North was better funded and equipped), and both its soldiers and leaders — Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis, in particular — were to be glorified as heroes. Women weren't forgotten either, idolized just as much as the men for their support and sacrifice.

In short, the Lost Cause was a way to romanticize the Civil War-era South. That's really the main thing.

White supremacy and the United Daughters of the Confederacy

If you wanted to get technical, the United Daughters of the Confederacy isn't out there on the streets, lauding the righteousness of white supremacy. Or, at least, they aren't anymore (via ABC 24). And, in all honesty, it doesn't seem like the sort of thing that anyone would want to go directly screaming from the rooftops. In the past, though, members of the UDC have been pretty clear supporters of white supremacism. Part of that has to do with the people that they were affiliated with, like Julian Carr, who was known for his 1913 speech in which he wanted to "Praise God" that "the purest strain of the Anglo Saxon is to be found in the 13 Southern States."

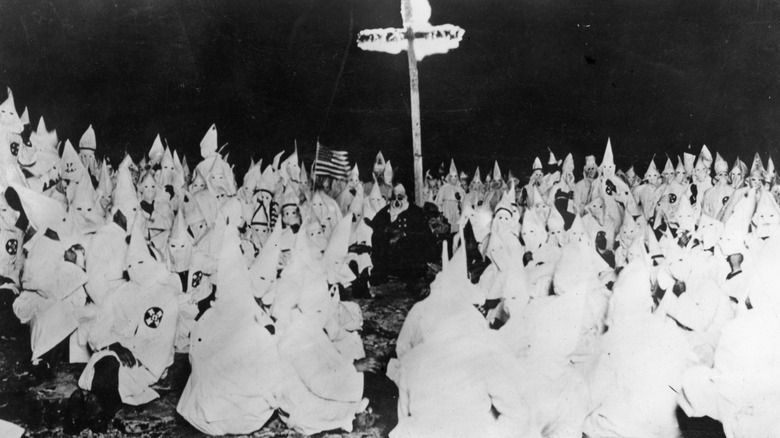

But, alright, Carr wasn't part of the UDC. Well, the UDC was responsible for choosing the textbooks used in schools, many of which had significant slants toward white supremacy. "The Ku Klux Klan or Invisible Empire" was a supplementary reader endorsed by the UDC in 1915, which, in effect, reduced African Americans to idiotic, brutish savages who were entirely to blame for the economic depression that hit the post-war South. Meanwhile, the "best class of white people" were unrightfully vilified.

Oh, and there was the time when the national UDC president gave a speech in the early 1900s, which justified everything they did as the best way to ensure white, Southern Americans' "supremacy in [their] own land."

The United Daughters of the Confederacy and glorifying the KKK

As Facing South explains, a glorification of the Ku Klux Klan — particularly the version around during Reconstruction — is sort of a staple of the Lost Cause mythos. With the United Daughters of the Confederacy ascribing to that mythos, their glorification of the KKK almost seems like a given.

High ranking officers in the UDC openly praised the KKK, and the organization itself would actually host essay contests well into the 1900s with topics like "The Origins of the Ku Klux Klan" (sure, that could be tackled objectively, but other topics included "The Right of Secession," so take that as you will). They also associated with others who deified the KKK, including a leader of the Carolina Rifle Club, which marketed itself as an alternative to the KKK.

But there's also the textbooks they approved of for use in schools, like the "Young People's History of North Carolina." The book covers a lot of time, but when it came to the KKK, things got creative. They're described, effectively, as vigilantes, doing illegal things, but only because it was the only way they could help their "suffering people" (Southern whites, in this case). They would "pass as silently as the midnight ... not a ghost of a whisper would be heard" in order to keep the peace and punish evil, scaring "ignorant whites and Blacks" into submission. All told, the Reconstruction-era KKK was made out as a mythical force of good.

The Rutherford Committee

If you wanted to get into what really put the United Daughters of the Confederacy on the map, here's the short answer: textbooks and schooling. Where the Lost Cause mythos romanticized the Confederate South, the UDC played a huge part in pushing that narrative to younger generations.

And a lot of that really got started around 1919 with something called the Rutherford Committee (via Facing South). Named after Mildred Lewis Rutherford (pictured above), a notable member of the UDC, the Committee actually pulled people together from a bunch of different Confederate heritage associations, uniting for the express purpose of teaching the Lost Cause through history books. As for how they would do that, well, it basically involved instituting a form of censorship. Individual schools wouldn't have the power to choose their own textbooks anymore; instead, that job would fall to a separate division, created solely to approve textbooks, and filled with people who were all pro-Lost Cause.

Now, to be completely fair, the Rutherford Committee and the people with the job of approving textbooks wasn't the same as the UDC. But that setup made it super easy to dictate exactly what younger generations would be learning, ensuring that they would only hear about the Confederate South in the most positive light. The UDC could petition a single body, and all of a sudden, they could ensure that Southern youths were learning only what they wanted them to, or they could blacklist tons of books that didn't fit their version of history.

The United Daughters of the Confederacy tried to silence their opposition

Given that the United Daughters of the Confederacy was really active in trying to skew history to their perspective, it's no surprise at all that they faced a lot of opposition.

And where that becomes really clear is in the cases of particular authors who were attacked and bullied into silence. Per Facing South, Enoch Banks was one of those people. A university professor in Florida, Banks published an article in 1911 that argued that slavery — not secession — was the root cause behind the Civil War. Pro-Lost Cause groups like the UDC more or less called for his head. All of the drama lost him support from his own university and ended his career.

Then there was the entire mess that was the Muzzey Affair. Nationally known history professor David Muzzey wrote a textbook titled "American History." Despite not following the Lost Cause ideology, the North Carolina textbook commission approved it in 1920; Muzzey's contract wasn't up yet, so they had no choice but to approve it. Not that it mattered to the UDC. For about two years, they launched media campaign after media campaign, deriding Muzzey's book and hounding public officials with letters. By 1922, Muzzey's contract was over and the book was dropped, at which point the UDC was proud to announce that they had "the sympathy... of the State Board of Education" (as if they had done something more dramatic than wait for a contract to expire).

The United Daughters of the Confederacy's altered history had long-lasting results

Going deeper into the 20th century, the power of the United Daughters of the Confederacy began to wane; there just weren't as many people alive directly connected to Confederate veterans.

But that didn't mean that the influence of the UDC wasn't felt for decades to come. Those same Lost Cause-centric textbooks were being used in the South well into the 1970s and 1980s, with some schools in Texas actually still teaching the Lost Cause ideology as recently as 2010. Studies referenced by Facing South also claim that, as of 2018, a majority of Americans didn't fully understand the role that slavery played — and the effects it's left behind — in American society, and in 2011, almost half of Americans would cite states' rights as the cause behind the Civil War. The Lost Cause philosophy is still hard at work.

And if you want anecdotal evidence instead, Smithsonian Magazine discusses what it's like visiting Confederate memorials. Actors, volunteers, and guides will all talk about the history of the South, and its textbook Lost Cause arguments. Southern slave owners were actually humane, and the slaves were happy with their situation — better off for it — because "bad" slave owners were actually a rarity. Or you might be told that the idea of the Civil War being fought over slavery is just modern political correctness, accompanied by a literal banner screaming in all capital letters that the view isn't supported by historical evidence.

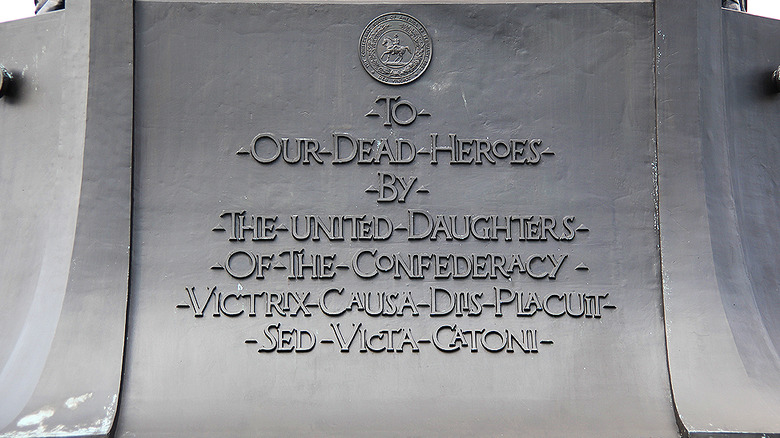

Statues are a big thing for the United Daughters of the Confederacy

For all the various controversies that the United Daughters of the Confederacy has been caught up in the past, there's one thing in particular that, as of writing, is a massive issue: Confederate monuments and statues.

To say that the upkeep of Confederate monuments is a controversial topic would be really understating things. Smithsonian Magazine calls them a remnant of what should be a bygone era, while The Guardian includes quotes from activists explaining that keeping these monuments standing is vile in and of itself. Maintaining these Confederate monuments is about equal to celebrating what the Confederacy really stood for — racial inequality and slavery. They're monuments to a long history of violence toward African Americans — injustice, plain and simple. There have been protests and counter-protests going back and forth over what to do; sometimes, paint gets splashed on the statues, and other times, people are killed in riots (via Newsweek).

Where the UDC gets involved is that they're often the ones behind hundreds of these statues and monuments existing in the first place. At best, they've been silent on these issues (but still complicit by not taking a real stand against injustice). They rarely offer statements regarding the fate of these statues, except to express their disappointment in an America they say they don't recognize. But at other times, they've been actively pushing lawsuits to try and fight the removal of these statues and holding onto their Lost Cause ideals.

Where are the United Daughters of the Confederacy now?

With the Civil War and the fall of the Confederacy well over a century and a half behind us now, the United Daughters of the Confederacy is sort of dying off, with only about a quarter of the membership that they had around World War I (via The Guardian). For that matter, current members actually aren't even sure if the group will last another generation — Newsweek goes so far as to say they're desperate for more members.

On top of that, they've changed over the years. They're the least vocal and aggressive of the Confederate heritage societies that still exist today, with some of their beloved monuments actually coming down without much fanfare at all. The members themselves are also considering different stances regarding Confederate monuments, with some of them at least agreeing that the statues could be relocated (not quite what protestors were asking for, but more than nothing). One of their rare statements adds that they denounce "any individual or group that promotes racial divisiveness or white supremacy."

That said, they still hold to their Lost Cause roots. The same statement also voices disappointment that anyone would be offended by the Confederacy and expresses hope that their Confederate memorials can remain standing to honor the dead. Their website has still claimed that slaves were happy and devoted, and they spread those ideas while claiming to just want to educate. It's pretty much the same as what they did a hundred years ago.