The Crazy History Of Water Wars

As such an essential part of life, it stands to reason that water would be involved in human conflicts. But water conflicts, or water wars, describe a variety of different situations that aren't just limited to disagreements over who gets which water. In general, water conflicts have rarely been directly focused on the scarcity of water, and instead have incorporated water in the pre-existing conflict. But as water scarcity grows, so do water-related disputes.

Sometimes water conflicts are manufactured by people, and other times they are exacerbated by people. And in some places like Southwest Asia, water conflicts have occurred for millennia. But with climate change bringing higher temperatures and more frequent droughts, many worry that water conflicts will become more common as time goes on. As of 2020, it was estimated that over two billion people in the world were living in countries that experience "high" water stress. And unfortunately, this number is only expected to grow. This is the crazy history of water wars.

What is a water war?

A water war, also known as a water conflict, typically occurs when a dispute arises around water resources. However, although water may be the trigger for the conflict, it can also be one of the casualties of the conflict or can even be used "as a weapon of war." And according to "Water and Conflict," there are various scales of conflict. Water wars may occur at a regional level, a national level, involve a border dispute, or even occur between countries that don't share a border.

While most water wars are centered around access to freshwater resources, conflicts can also occur over saltwater. However, water wars are often concerned with water to be used for drinking, energy generation, or irrigation. Typically, water conflicts lead to "more water-sharing agreements than violent conflicts," according to "Global Water Security," and there are international treaties having to do with fresh water resources dating back centuries.

But this doesn't mean that all water wars are nonviolent, and most water conflicts occur in the context of violence. And as freshwater resources decrease, disputes over water resources are increasing at both local and international levels. Meanwhile, attacks on water and sanitation facilities have been seen in numerous regions, as access to clean water is weaponized amidst other conflicts.

Why do water wars happen?

Water conflicts occur for several reasons. Out of all the water in the world, less than 0.01% "is available for human use in lakes, rivers, reservoirs, and easily accessible aquifers," according to "Water Rights and Water Fights." And since more than half of all the water in all the rivers is shared by countries, this means that "many countries are highly dependent on water resources that originate from outside their national territory."

While water scarcity may be caused by natural conditions, such as lack of rainfall or lack of access to an adequate water source, ECDPM writes that "it is often created or at least worsened by over-abstraction, unsustainable land use, deforestation, intensified irrigation, and modification of ecosystems."

However, water scarcity is rarely the sole instigator of an armed conflict. Often, water conflicts can arise if there's a history of combat in the region or if the region has experienced rapid urbanization, population growth, and industrialization. Water wars can also be instigated by "disputes concerning environmental and resource issues." Since over 260 rivers are shared by at least two nations, writes The New Humanitarian, conflicts can arise regarding the impact of one nation's "water use opportunities," such as the dispute between Ethiopia and Egypt.

What were some of the first water wars?

One of the earliest recorded water conflicts occurred over 4,000 years ago between two city states in ancient Mesopotamia. During this time, there were often conflicts over the diversion of water for the irrigation systems between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Water Conflict Chronology writes, for example, that between 2500 and 2400 BC, Urlama, the King of Lagash, diverted water from the Tigris using canals and cut off the water supply from the land of Umma.

Water conflicts of this variety are what led to the creation of the 1790 B.C. Code of Hammurabi, which listed "several laws pertaining to irrigation that addressed negligence of irrigation systems and water theft," writes Tug of Water. And less than 100 years later, Hammurabi's grandson would dam the Tigris during a failed attempt to stop the rebels led by Iluma-Ilum.

Water was weaponized early on as well. The Atlantic writes that in the sixth century BC, Assyrians used rye ergot to poison water wells, and in 596 BC, Nebuchadnezzar attacked the aqueduct used by the city of Tyre in order to "end a long siege." Ancient Greece also saw its share of water wars. Despite the fact that at the time, it was customary "not to damage sacred areas, such as the waters at the Delium temple," during the 424 BC battle of Delium, Athenians deliberately contaminated the temple waters.

Water wars over the years

Water became an instigator, casualty, and weapon in conflicts throughout history. During the Middle Ages, the Crusaders' water was cut off by Saladin at the Horns of Hattin in 1187, when he filled wells with water and destroyed the Christian villages that would've given the Crusaders water. In Mughal India in the 1260s, reservoirs and water canals were also purposefully dried up during local protests.

During the Black Death, water was also turned into a source of blame. According to Columbia University Libraries, Jewish communities were accused of intentionally spreading the bubonic plague by poisoning wells, which led to "a series of terrifying massacres" against Jewish communities in the German Empire in the 14th century. Some of the earliest accusations come from 1319. But these attacks weren't limited to the German Empire. Some of the first pogroms occurred in 1348 in Languedoc and Catalonia, and in Savoy, the Jews accused of well poisonings were put on trial for the first time.

In the south of France, lepers were also accused of attempting to spread leprosy by poisoning water sources as well.

Modern water wars

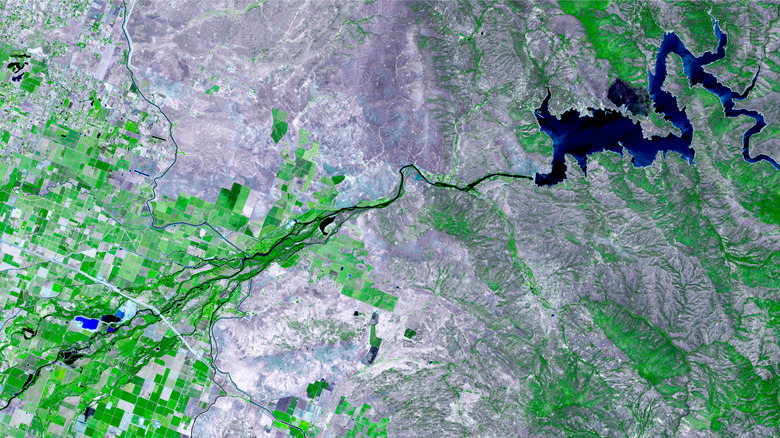

Water wars continued into the modern era as both a target and trigger of conflict. Open Rivers writes that in the beginning of the 20th century, the Los Angeles Valley aqueduct and pipeline was bombed numerous times "in an effort to prevent diversions of water from the Owens Valley to Los Angeles." And during Germany's colonization of Namibia, the invaders reportedly poisoned desert water wells while simultaneously forcing Herero and Nama people into the desert.

The proliferation of water was also used in times of conflict. In 1938, President of the Republic of China Chiang Kai-shek ordered a series of flood-control dikes along the Huang He (Yellow) River to be destroyed, in an attempt to flood the areas where the Japanese army was encroaching. Between 3,000 and 50,000 square kilometers were flooded, and up to one million people Chinese people died as a result.

Water-related conflicts and violence have not declined in the 21st century, although now "the vast majority of [water-related violence involves] non-state actors: individuals, non-governmental militias, and civil conflicts, rather than nation-to-nation disputes." But as MEI notes, nations also continue to be "at odds over water issues." But often, water scarcity isn't itself the issue. Instead, "maldistribution of water or of water infrastructure," often exacerbated by dams and diversions, result in water shortages and play a role in subsequent conflicts.

Using water to oppress

Throughout its colonization of Palestine, Israel has weaponized water against the Palestinian people. During the 1948 Nakba, Zionist forces poisoned an aqueduct in Acre with typhoid, resulting in over 120 deaths. The Jordan River was also a factor in the Six-Day War in 1967. And ever since Israel occupied the West Bank in 1967, Palestinians have been subjected to "discriminatory water-sharing agreements," according to Al Jazeera. Due to these agreements, Palestinians are unable to develop their own water infrastructure and are forced to become "water-dependent on Israel." Climate Diplomacy also writes that Palestinians pay almost three times more for water than Jewish settlements. And while Israel "has been over-pumping aquifers since 1970," water restrictions are imposed on Palestinians.

In places like Gaza, Amnesty International reported in 2017 that up to 95% of the water supply "is contaminated and unfit for human consumption." However, Israel doesn't permit the transfer of water from the West Bank to Gaza.

According to The Conversation, "Israel controls more water than Jordan and the Palestinians combined, and more than double its entitlement when measured against the principles of the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention." Meanwhile, the 2017 water deal only went on to further "reinforce Israeli occupation, colonization and ghettoization," according to Stop The Wall.

Tentative cooperation despite tensions

Despite the history of tensions between Armenia and Turkey, the two nations are considered an example of how countries can share transboundary waters relatively equitably. Climate Diplomacy writes that the Arpacay River, which forms the border between Armenia and Turkey, has been shared equitably by the two countries since the 50-50% allocation of the 1927 treaty that Turkey signed with the Soviet Union. The two countries also manage the Arpacay-Akhourian Dam jointly and created a Turkish-Armenian inter-state commission on the use of the dam in 2004.

However, there are loopholes in the treaty, including "the absence of agreement on water quality standards and water protection." And despite the appearance of diplomacy, the two nations insufficiently exchange data on water. However, one thing that helps is the fact that the Armenian side's water gauges are located on the Turkish side and the Turkish side's gauges are located on the Armenian side, which according to "Promoting Development in Shared River Basins," allows each side to "constantly monitor each other's consumption."

The fact that Armenia and Turkey continue to maintain the agreements signed during Soviet times does little to address the "unsettled issues" between the two countries, and requires greater communication. One such issue is the fact that Turkey's water development projects will most likely have an effect on freshwater ecosystems and flow patterns, which will in turn affect water infrastructure upstream.

The Mesopotamian Basin

Shared by Iraq, Iran, Syria, and Turkey, the Euphrates-Tigris Basin and its water use has been the source of conflict for decades. Especially starting in the 1960s when, according to Climate Diplomacy, the three nations "initiated large-scale water development projects in an uncoordinated way," affecting the river flow.

According to MEI, there are also significant tensions between Iran and Iraq. While Iraq gets almost all of its water from the Tigris and the Euphrates, Iran is building dams that will ultimately divert some of the river's water, "causing alarm and creating major water shortages for Iraq." As of 2021, the flows of at least two tributaries of the Tigris have "fallen significantly," with almost an 80% drop in water levels. Iraq's water supply is also threatened by the dams that Turkey is building, known as the Southeastern Anatolia Project. According to the Financial Times, the dams built by Turkey also result in "higher salinity levels downstream hitting crop yields and [damage to] the wider ecosystem," effects which have been recorded by Iraqi environmentalists.

Some governments have also tried to claim the rivers as their own. In 1992, then-Turkish Prime Minister Suleyman Demirel claimed, "The water that flows to Turkey from the Euphrates, Tigris and its tributaries is Turkish ... We are not saying to Syria and Iraq that we share their oil resources ... They have no right to say that they share our water resources."

A tenuous treaty

Before the signing of the Indus Waters Treaty in 1960, British India and West Pakistan engaged in a series of water conflicts, such as when India withheld water from flowing from canals into Pakistan. Ultimately, the treaty brokered by the World Bank gave the eastern rivers to India and the western rivers to Pakistan. The treaty also mandated the creation of the Permanent Indus Commission, which was instrumental in solving various disputes over the years.

In 2017, however, the relations maintained by the treaty were threatened when India finished building the Kishanganga Dam in Kashmir and continued to build the Ratle hydroelectric power station on the Chenab River. According to Climate Diplomacy, the year before the Indian Foreign Ministry spokesperson had even suggested that India might withdraw from the Indus Waters Treaty.

The Baglihar Dam in Kashmir has also been a source of contention ever since the project was announced in 1999. And according to TRTWorld, after Kashmir's semi-autonomous status was revoked by India in 2019, this gave the Indian government "full control over water flowing from the Himalayan Plateau into Pakistan." This is particularly worrisome for people in Pakistan, especially since the Indian government already threatened to divert Pakistan's water in 2016.

Water wars in the Mekong basin

One of the largest and longest rivers in the world, the Mekong River originates in China and then proceeds to flow through Laos, Myanmar, Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam before emptying into the South China Sea. During the 1990s and the 2000s, China began investing heavily in hydro-power installation, according to Climate Diplomacy, with plans for at least 20 dams in total. However, while China claims that the downstream effects are "negligible," countries like Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam have already experienced adverse effects as a result of China's hydro-power projects.

And Asia Times writes that because of its dams, "China now has the power to completely stop the flow of water to downstream nations, a pressure point that could be used to devastate their agricultural economies and create food scarcity in the event of a conflict."

And as droughts become more and more frequent, China's dam network "gives it increasing leverage." But not all of these droughts are natural occurrences. In 2016, the Mekong Eye reported that the Mekong Delta in Vietnam was experiencing its worst drought in 100 years, which experts believe is related to the various "mega-dams along the river."

The water war of Cochabamba

In the city of Cochabamba in Bolivia, after the city's municipal water supply was privatized, protests erupted from November 1999 to April 2000, becoming known as the Cochabamba Water War. According to Environment and Society, the Bolivian government essentially "put the city's water supply up for auction" and after the water company Aguas del Tunari, owned by an American company, won the contract, they raised the price of water and "many poor people were at risk of losing access to water." And Frontline writes that "although a major American corporation was at the center of the conflict, not a single U.S. newspaper had a reporter on the scene."

Climate Diplomacy writes that during the protests, police and military intervention led to at least seven people being killed. "A peak in the protests was reached when the video of a military leader shooting a student to death went viral."

After the video went viral, the government decided to end its contract with the water company, "officially stat[ing] that it was unable to guarantee the safety of the executives of the water company." And although Aguas del Tunari filed a lawsuit against the Bolivian government for almost $50 million, they dropped the lawsuit in 2006.

Dam'd if you do

After Ethiopia announced its plans to build the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam on the Nile River in 2011, Egypt almost immediately voiced their opposition, citing concerns about a diminished water supply, a concern echoed by Sudan.

The Africa Report writes that the dam's hydropower is meant to provide power to citizens of both Ethiopia and Sudan, in addition to preventing flooding, "particularly in Sudan." However, there's the potential that the dam will also stifle the downstream flow of the Nile River. This is a legitimate concern, especially since as of 2020, the water level of the river has already been decreasing and the lack of water has already resulted in people being displaced. At one point, the water levels were so bad that people feared that the dam was already being filled, writes The Guardian.

Despite these concerns, the construction of the dam carried on, and in 2021, Ethiopia began filling the dam. According to Al Jazeera, in response, Egypt claimed that the filling of the dam was "a violation of international laws and norms that regulate projects built on the shared basins of international rivers." Egypt considers the dam to be "an existential threat," especially since the country depends on the Nile River for almost the entirety of its drinking and irrigation water.