What It Was Really Like Being A Spectator In The Colosseum

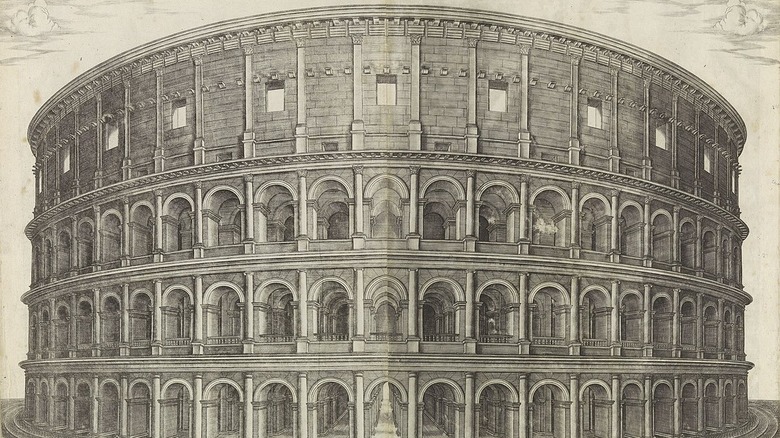

Even today, the Roman Colosseum is an incredible sight to behold. Before two thirds of the giant structure was destroyed by natural disasters or plundered for its stone, the great arena would have been even more breathtaking to ancient spectators when it first hosted an audience in A.D. 80. It did not take long before the towering edifice became one of the most popular buildings in the legendary capital.

In the days of the Roman Empire, the Colosseum would have been known officially as the Flavian Amphitheater, named after the emperor who had it built, Vespasian, and the Flavian Dynasty he started in the late first century A.D. But like all emperors, the Flavians were called Caesar while they ruled, so the grand arena was most likely referred to as "Caesar's Amphitheater" during their reigns. The name "Colosseum" originated centuries later around the 11th century A.D., which may have come from the colossal statue of Emperor Nero that was located just outside the amphitheater. The arena also had other less common names, such as "hunting theater" and "Ovum," meaning "the Egg."

However, to most of those living in Rome at the time, the Colosseum was simply called "the arena" or "cavea," the term used for stadium seating. As the largest amphitheater of the ancient world, it's not hard to understand why the Colosseum was the only arena that truly mattered in the city. During an age when extravagant entertainment was particularly hard to come by, Rome's best arena provided more thrills to spectators than other attraction of the age.

The entertainment was a distraction for the common people

Unfortunately, many Romans were poor and lived hard lives, barely getting by with a meager living. Times were tough even if they were lucky enough to have some sort of profession, so a brief escape from their hardships was quite enticing. There was no price for admission into the Colosseum, so literally any Roman could enjoy the elaborate shows and spectacles, according to Learn about Italy. Free bread was also given out to the crowd in between shows, which was a great way to attract those with empty stomachs.

True to the saying, "there's no such thing as a free lunch," however, the emperors got much back in return for putting up "free" performances at the Colosseum. Not only did it increase their popularity, but the emperors quickly figured out that they could more easily control the people by providing food and lavish entertainment. The poet Juvenal brilliantly pointed this out in his now-famous phrase "bread and circuses" in the late first century A.D.

There were many large corridors and stairs to give spectators easy access to their seats

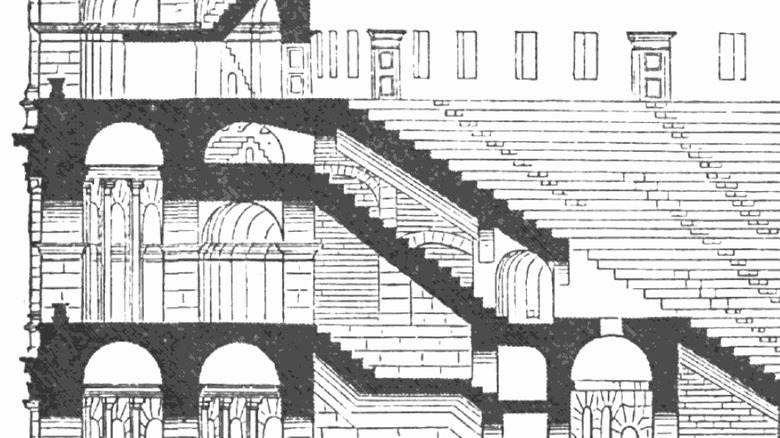

It was not easy to get 50,000 spectators into a large arena in an orderly fashion, yet the Romans managed to pull this off through brilliant architecture using numerous arches and vaults, which gave it a honeycomb look to spectators who approached the Colosseum from outside. The four-story structure had four grand entrances for the upper class, along with other openings that were all numbered for everyone else. Like modern-day sports arenas, tickets to the Colosseum were given out to spectators first before they could enter, which were clay tokens that told their section, row, and seat numbers, according to Gizmodo. An example of an inscription would be CN VII, GD X, LOC IV, meaning the fourth seat of the tenth row of section seven.

The Romans were well-aware of the possible danger from thousands of people moving through passages, so they designed the building with "safety zones" near stairways and entrances in order to limit congestion, also like most modern stadiums. The Colosseum was also designed in a way that simplified the inside of the structure as much as possible. Entrances only led to specific sections of the arena, so the first door a spectator entered determined where they could go, cutting off their access to the rest of the building. This allowed spectators to find their seats quite easily with their tickets.

There was assigned seating based on social class

Any Roman citizen may have been able to get into the Colosseum, but their status in society ultimately determined where they could sit. The stadium seating of the amphitheater was divided into five tiers based on social class, says Peter Rose in his article, "Spectators and Spectator Comfort in Roman Entertainment Buildings: A Study in Functional Design." So, unless someone was trying to get away with something, they knew what entrance into the arena they were supposed to take in order to get to the appropriate section. Yet it is very possible that scalpers existed, according to Gizmodo, so spectators probably found ways around the rules to get better seats.

The first tier was right in the thick of the action as the closest to the arena sands. These prized seats were strictly meant for the most powerful in Rome, specifically the emperor, senators, and religious officials like the Vestal Virgins. The next tier was for wealthy businessmen, the third was for any commoner who had enough wealth to own a toga, the fourth was for men who could not afford one, and finally, the upper gallery was for lower-class women and children, along with slaves. Aristocratic and wealthy women, on the other hand, could sit in the lower tiers with their rich husbands.

The conditions of the upper tiers were not great for the poorer spectators

The assigned seating of the Colosseum clearly favored the rich, who could see and hear the shows better than the sections above them. The women and children on the final tier, the upper gallery, had it the worst. According to the BBC, these unfortunate spectators were so high up that they were nearly 330 feet away from the arena sands, making the gladiators and other performers look like specks in the distance.

Another reason wealthier audience members had a more comfortable experience was because they could afford to bring chairs or cushions to sit on, whereas much of the poor were stuck with sitting on the bare stone seats. Some avoided this by brining planks of wood, which was a slightly better experience.

Plus, it is quite possible that, aside from the first and possibly the second tiers, many spectators at the Colosseum only had around 16 inches of space to sit and 28 inches of leg room. The experience may have been somewhat claustrophobic for quite a few people because that's basically less space than an economy airplane seat.

There was a really big curtain to provide shade from the sun

The poorer spectators of the Colosseum may have been crammed together high up above the action, but the wealthy had to sweat from the heat of the summer sun while the men and women in the upper tiers sat in the shade. The giant awning above the spectators was called the velarium and consisted of long strips of linen or wool that were tied with rope to 240 poles attached to the top of the Colosseum, according to the University of Chicago. But the curtain still left much of the amphitheater open and could only shield around one third of the audience.

A unit of 100 sailors was in charge of raising and lowering the huge awning with the use of drum beats to synchronize their actions. When unfurled on days that the wind was abnormally strong, the fabric would flap with such intensity that it could sometimes sound like thunder above.

On particularly hot days, further relief was provided by mist scented with balsam or saffron that was sprayed over some of the crowd, though this luxury was most likely for the front rows, not the upper tiers of the seating.

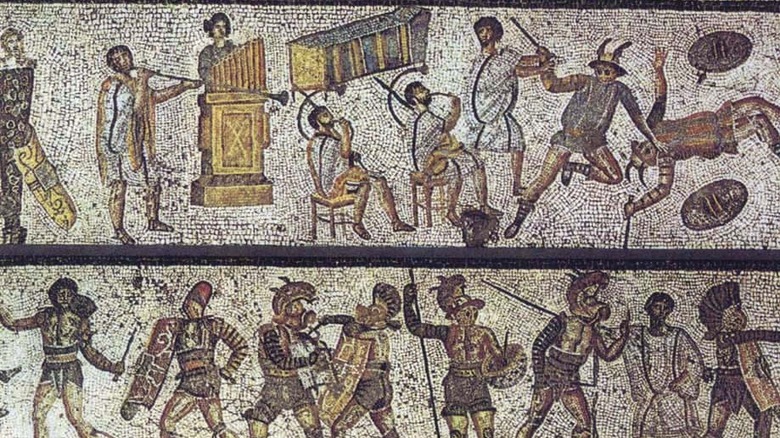

Music was a key part of entertainment at the Colosseum

After the spectators had reached their seats, the entertainment began with a parade with trumpeters and other performers, including the gladiators without their helmets on so their fans could see their faces as they waved to them and cheered. It is also very likely that those musicians played as accompaniment to the other performances throughout the day, along with a water organ, even during gladiatorial fights, says M.C. Bishop in his book, "Gladiators: Fighting to the Death in Ancient Rome." Some things never change, as organs are a major part of baseball games and other sports events to this day.

Instruments were also essential to the inner workings of the hypogeum, which was the basement beneath the arena. In an environment similar to backstage at a theater performance, workers used drums, horns, and organs as signals in order to coordinate the intricate steps needed to ensure the shows went on smoothly. With the roaring crowd above and the various noises of machines, animals, and people below, the instruments were the only way the hypogeum workers could communicate.

Prizes were given out to lucky Colosseum spectators

As another way to gain the favor of the mob, a common practice of the emperors was to randomly distribute gifts to the audience during performances. These prizes could be all sorts of things, from fresh meat, desserts, and other food to domesticated, or sometimes wild, animals, says Christopher Epplett in his book, "Gladiators & Beast Hunts: Arena Sports of Ancient Rome." Some spectators were fortunate enough to receive money or even the deed to an apartment.

At first, small wooden balls with special markings were launched into the crowd during mini-intermissions, kind of like modern T-shirt cannons. The spherical tokens could then be exchanged for a prize, depending on whatever marks were etched in. However, the ticket system of the Colosseum quickly replaced the old way, and the clay tokens began to serve as both admission and lottery tickets. It also wasn't uncommon for huge amounts of snacks to simply rain down upon the audience instead of the wooden spheres.

Concessions and souvenirs were available to buy

Near the Colosseum and other Roman amphitheaters, the streets were filled with the delicious aroma of numerous small shops selling all sorts of ancient fast food. According to HistoryExtra, spectators could buy fresh bread, fruit and vegetables, hot sausages, chickpeas, and pastries, all on the go. Other venders sold items like gladiatorial programs or trinkets such as oil lamps with images of famous gladiators painted on them.

Once within the great arena, spectators could also partake in the various snacks offered to the audience by stewards during short breaks in the action. Not only were there trays of pastries, cakes, and dates available, but also jugs of wine to disperse to the crowd. However, many in the audience were still expected to take a lunch break during the midday entertainment that served as a longer intermission. Most didn't go far but just purchased food and drinks at the counters of the plentiful taverns and bars.

There may have been naval battle reenactments in the Colosseum

Since it must have been a nightmare to organize, filling an amphitheater with water and showing a simulated naval contest was rare. The Romans attempted the impressive feat only four or five times, but one or two of those special occasions are even more extraordinary cause they took place in the Colosseum, according to Atlas Obscura.

In A.D. 80, Emperor Titus held a grand celebration over multiple days, in which one of the main events was a mock sea battle in the Colosseum that may have involved as many as 3,000 men. But since it would have taken so much water to fill the massive arena floor, the water level was probably low with smaller replicas of ships. There might have been one more simulated battle in the Colosseum in A.D. 86. Reportedly, this one involved a torrential rainstorm, and every single gladiator involved and even spectators died.

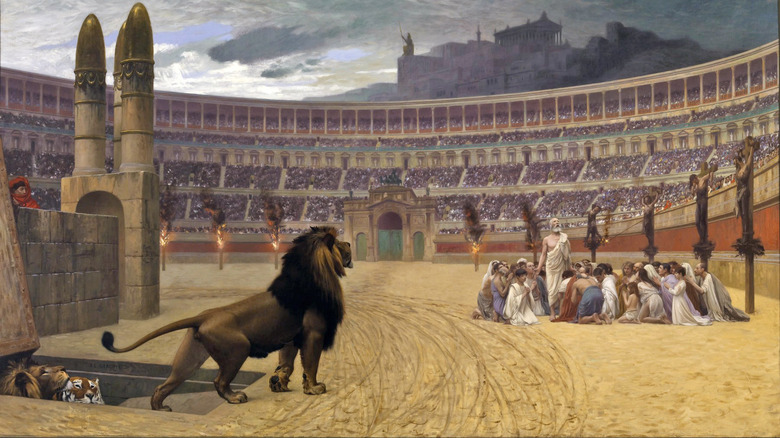

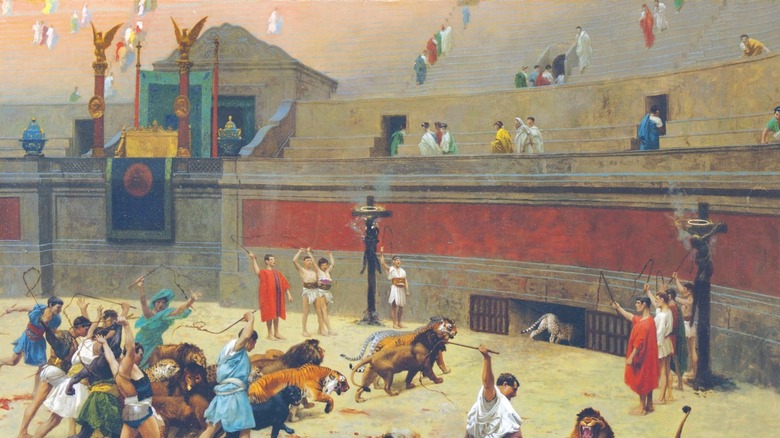

Specialized hunters fought exotic animals

After the initial parade, entertainment typically began with theatrical duels between combatants often meant to be comical in nature, with dwarfs, women, and the handicapped as the performers. Then came the first of the main events. Aside from gladiator fights, the other most popular attraction commonly featured at the Colosseum was wild animal events where spectators could see exotic beasts from all over the known world. According to Walks of Italy, this included bears, elephants, hippos, bulls, lions, tigers, gazelles, giraffes, ostriches, hyenas, crocodiles, boars, and several others.

Some animal shows had beast handlers that enticed animals to fight each other or attack other humans. Even more popular were the shows featuring exotic animals that were slain by professional hunters called venatores. The underground complex beneath the arena had nearly 200 cages to contain the various beasts, along with ramps and lifts that allowed the animals and stage props to quickly enter the show.

Unfortunately, significant amounts of living creatures were slaughtered during these gruesome spectacles. For the opening celebrations for the Colosseum (which lasted 100 days) alone, a horrifying number of 9,000 animals were killed.

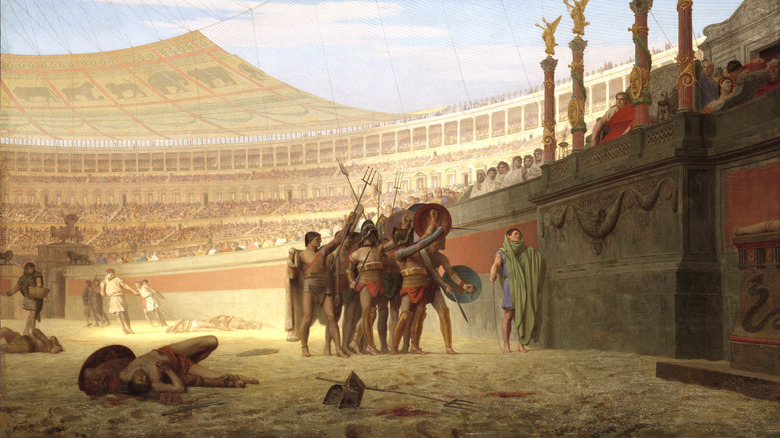

The best gladiators were seen as celebrities to spectators

After the beast hunts and an intermission came the most popular shows of the day, the gladiator fights. For many spectators, gladiatorial combat was the main event, since the warriors were viewed as the celebrities of the age. At the time, images of their likenesses were displayed in public places, there were clay figurines of gladiators as children's toys, and gladiator sweat was seen as an aphrodisiac and even mixed into women's cosmetics, according to History.

The grand arena would have erupted in cheers from the crowd as the fight ensued until a gladiator was left standing victorious. If still alive, losing fighters had a chance for mercy by dropping their weapons and raising one finger. Spectators would have then had a lot of emotion invested in the outcome as they pleaded with the emperor through hand gestures or waving a cloth to let their beloved combatant survive after losing the contest. On the other hand, if their hero had won the fight, the crowd may then be out for blood and encourage the emperor to give the signal for the gladiator to execute his defeated foe.

Many spectators bet on arena contests

Another major link between past and present is the timeless frequency of gambling for sports like fighting and racing. Gladiator contests in the Colosseum were not only a great joy for spectators who got to see their favorite celebrity compete in the most impressive arena, but the Romans also got much thrill out of betting on their chosen warriors, too.

Even though gambling was technically illegal, says The Infographics Show, it was common among aristocrats, the lower classes, and pretty much everyone from all walks of life. Even gladiators bet on fights involving their belligerent colleagues. Obviously, bets were traditionally made before the combat began, leading to a great buildup of suspense before the fight. So, when the crowd cheered with passion over the life of a defeated fighter, it might also have had much to do with the amount of money that was on the line, as well.

Criminals were executed as part of the entertainment

Around noon, there was usually a long intermission so that spectators could leave, take a break from sitting, and eat lunch. But for those who stayed, public executions were staged as entertainment called the ludi meridiani, or "midday games," says Smithsonian Magazine. All sorts of prisoners, from criminals to hostile barbarians, were released into the arena and slain in a brutal way to the cheers of the remaining crowd.

Most often, criminals were forced to fight each other with swords like amateur gladiator fights or were eaten alive by ferocious predators. During the reign of Emperor Domitian, some executions were staged as elaborate dramas, such as a performance where Hercules was literally burned alive on a funeral pyre and Laureolus was crucified. The gruesome ends were a terrifying way for emperors to warn the people to obey them and the law, or else...

Christianity ended gladiator fights

After Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire in the fourth century A.D., gladiator fights gradually fell in popularity. It got so bad around A.D. 399 that Emperor Honorius closed all the gladiator schools, says the World History Encyclopedia. Then, five years later in A.D. 404, spectators at the Colosseum witnessed a Christian monk who launched himself into the arena in an attempt to halt the violent combat between two gladiators. The furious crowd responded to the interruption by stoning the man to death.

The emperor was so upset about the incident that he forbade all gladiatorial fights going forward. But despite Honorius' decree, it is likely that one last gladiatorial performance took place decades later, yet when the imperial court transferred to Ravenna in A.D. 439, all gladiator matches truly ended not just in the Colosseum but in all of Rome.

On the other hand, wild beast hunts and criminal executions continued to be featured in the Colosseum, along with less violent wrestling matches, for over a century afterward. The grand structure did take some damage from an earthquake in A.D. 422, but significant repairs were made in 467, 472, and 508. However, after the sixth century A.D., when the Western Roman Empire was long gone, it fell into such disuse that grass began to grow on the arena floor. Over the centuries, neglect and pillaging led the great amphitheater to become a fraction of its former self.