What Hell Really Looks Like In The Bible

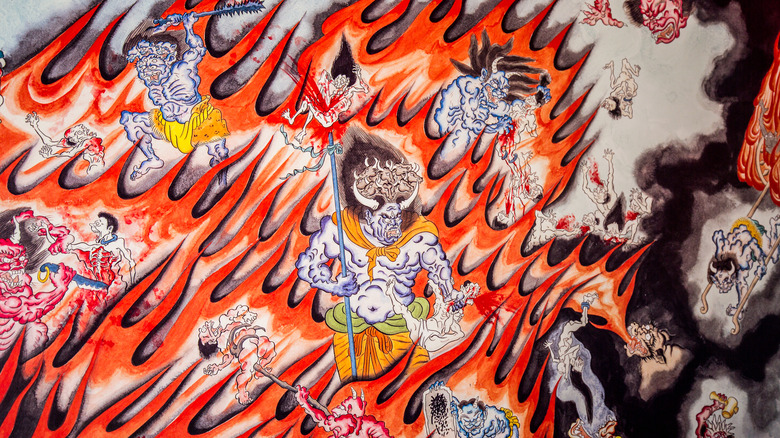

For 2,000 years, Christians have believed that there are two places (or three or more, depending on denomination) in which the souls of humans will spend part or all of eternity: Heaven, or Hell, or an intermediary place. And for most of those 2,000 years, what is meant by "Hell" has been anything but ambiguous, as "The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church" explains. The popular concept of Hell as being a place where sinners are separated from God to suffer for eternity is sometimes depicted as a sort of a massive torture chamber housed in another plane of existence, sometimes dark and cave-like, where those sent there are tortured in gruesome ways (not unlike the place depicted in the image above). Other accounts describe the place as a furnace, where the damned are tormented by eternal flames.

But is that how the Bible actually describes Hell? Not exactly, though there's more to the story. In essence, the popular image of Hell is one that is based not on scripture directly, but on inference, mis-translation, and a conflation of superstition with actual teaching. This image also got a little help from some of the most influential epic poets in the canon of great international literature. Let's take a look at what these various texts say about Hell and see how our present-day idea of the fiery place differs from that of the Bible.

The Bible uses different words that are translated as 'Hell'

In the Bible, four words, two of which mean effectively the same thing, are translated into English as "Hell," according to "The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church."

The Hebrew word "Sheol" (the Old Testament was written largely in Hebrew) and the Greek word "Hades" (the New Testament was written in Greek) both describe the same thing: a place where the dead abide. The exact definition is one of interpretation, but generally these two words refer to a sort of plane of existence where the dead abide — or a realm under the Earth, or the underworld, in some interpretations. Note, however, that these words are neutral, and the places described by them are not places of eternal torment, but just places. Period.

Elsewhere in the New Testament, the word "Gehenna" is translated as "Hell." In fact, "Gehenna," or the Valley of Hinnom, was and is a real place, and you can visit it today. In New Testament times, it was a trash dump, in which garbage was burned. A leper colony was located nearby — a literal "Hell on Earth," in a manner of speaking.

The fourth word translated as "Hell," however, is considerably more ambiguous, and its use, combined with other references elsewhere in the New Testament, is largely where the classical idea of Hell as a place of eternal torment comes from.

Lakes of fire

The one word translated as "Hell" in English translations of the Bible, and which describes the place as one of eternal torment, occurs in the New Testament, in 2 Peter 2:4. The Greek word translated there, "Tartarus," is actually a verb, and it is translated as "cast into Hell." Furthermore, Greek superstition — the writers of the New Testament lived and wrote within Greek culture and were largely writing to people who understood it — held that Tartarus was a sub-level of Hades, in which those sent there were indeed consigned to eternal torment, according to Greek mythology website Theoi.

Elsewhere in the New Testament, Jesus and/or the writers describe the fate of the wicked in horrifying terms, such as being cast into a lake of fire (Revelation 21:8). In the "Hell" entry in "The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church," the writer/editor notes that it's entirely possible that the colorful — even perhaps hyperbolic — language of John the Elder, the writer of Revelation, and others, possibly understood too literally, contributed to the popular understanding of Hell.

Poetry's influence on the modern conception of Hell

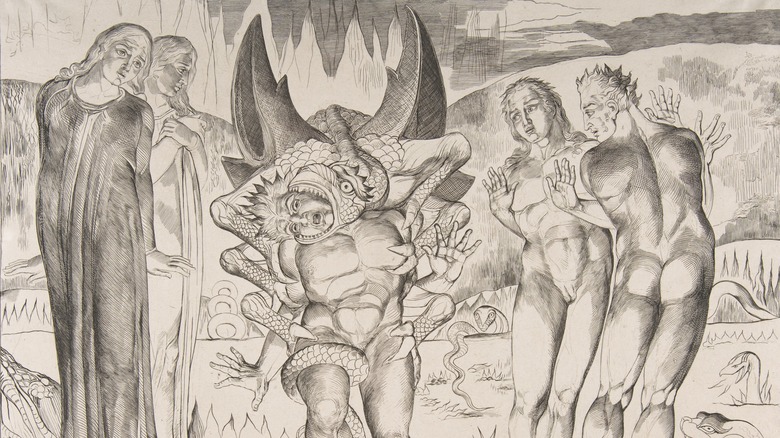

Funnily enough, our modern conception of Hell as a physical place full of liquid fire actually originates not from 2,000-year-old canonical scripture, but from wildly popular epic poems written centuries after the authorship of the Bible. While the Hell of the Bible may often be ambiguous and difficult to vizualize, this was not the case for epic poets who came later. According to The New Yorker, Dante, in 14th-century Italy, and John Milton, in 17th-century England, did more to create the vivid and haunting (though now largely trite) imagery the word "Hell" conjures in the modern mind than the authors of the Bible. The nightmarish scenes of demons the color of blood oranges roasting the souls of sinners in red-hot coffins or boiling them in rivers of liquid fire come straight from the pages of Dante's "Inferno" or Milton's "Paradise Lost."

So imagery like "people smothered in a filth/ That out of human privies seemed to flow," and "Floods and Whirlwinds of tempestuous fire," come, not from the Bible, but from the works of Dante and Milton, respectively. Such scenes of extreme suffering served as a threat to sinners for centuries, but some modern clergy are calling for a different, more Biblical conception of Hell. On his blog Pursuing Veritas, Christian Pastor Jacob J. Prahlow writes that conceptualizing Hell based on the works of epic poets, rather than the Bible, "seems a bit out of place."