American Insurrections And Rebellions You've Never Heard Of

In the first week of 2021, a riot in Washington, D.C., violently erupted into the capitol building. The world recoiled as what many called an insurrection or coup d'etat defiled one of the most hallowed buildings in the country, and the people's representatives fled and hid for safety. Of the many adjectives one could use to describe what happened that day (atrocious, treasonous, appalling, moronic, there are many more) however, unprecedented shouldn't really be one of them.

Not only are the streets of D.C. and halls of Congress not unused to violence, American history is replete with violent uprisings, bloody coups, and revolutionary attempts. In 1983, leftist revolutionaries exploded bombs at military bases as well as the United States Senate.

Sometimes it's easy to forget our past, so here are some of the American rebellions and insurrections you haven't heard of.

America was brimming with revolutions way before THE Revolution

The American Revolution didn't just happen. It's probable that the only reason it's known as THE revolution is that it was successful. In fact, there were many unsuccessful revolutions, rebellions, uprisings, and insurrections before the one every one knows about. People in America had been rebelling against colonial and local authorities long before they became actual Americans — often for many of the same grievances ultimately cited in the Declaration of Independence.

Exactly 100 years before the revolution, a young man named Nathaniel Bacon raised a thousand men against Virginia's governor (who was also his cousin) in what, according to the National Park Service, "was probably one of the most confusing yet intriguing chapters in Jamestown's history." This was swiftly followed by an uprising in North Carolina the next year about trade laws and import duties.

Then for two years in 1763, Pontiac's Rebellion — what the Washington Library calls "an unprecedented pan-Indian resistance to European colonization in North America, in which [14] Indigenous nations...challenged the attempts by the British Empire to impose its will" — wreaked havoc on settlers. Over 500 people were killed and anti-Indian sentiment grew.

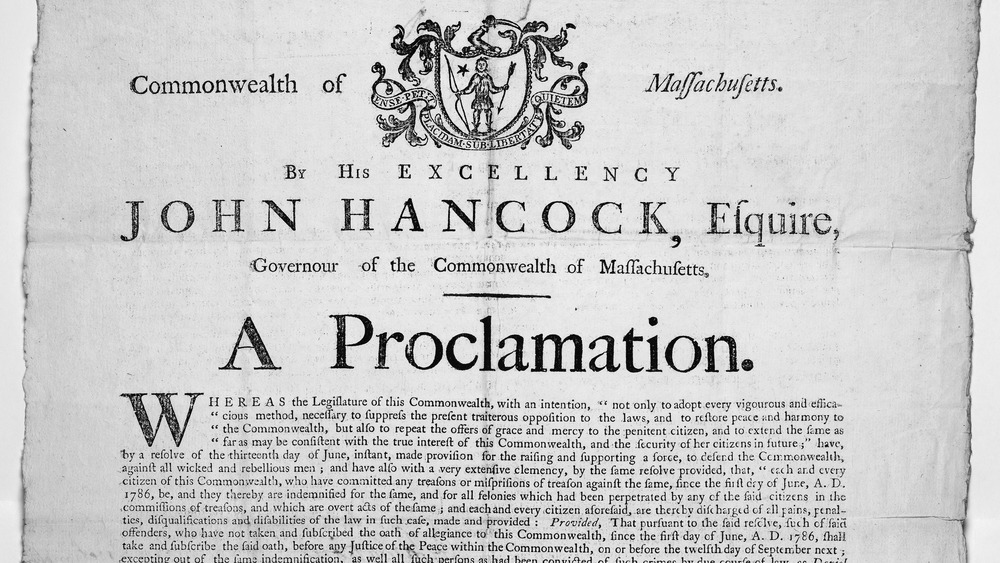

Shay's Rebellion helped create the Constitution

The American War for Independence was in no small degree about finances — "no taxation without representation" and all that. Even before they had declared, let alone achieved, independence the American states had to borrow money to fund their war against the crown. As early as 1775, "a cash-strapped Continental Congress accepted loans from France," says the U.S. State Department's Office of the Historian, and "paying off these and other debts incurred during the Revolution proved one of the major challenges of the post-independence period."

The infant United States of America, a new country with a brand new government, was actually pretty weak. The Articles of Confederation granted the U.S. central government very little power, especially to collect taxes. This left the nation unable to pay off their foreign debts, but the real problem was that the army and state militia veterans who fought in the war felt like they should be paid for it. It all came to a head in Massachusetts, as the Washington Library describes, when "these disgruntled former soldiers...led a violent uprising against debt collection," but these problems were widespread through the states.

The Massachusetts governor raised an army of militiamen, led by other Revolutionary War veterans and funded by private businessmen. When the insurgents tried to take an armory, the militia fired, and four men died. The incident highlighted the need for a change in government and a Constitutional Convention was called which led to the Constitution used today.

The State of Muskogee was a free Indian nation led by an Englishman

William Augustus Bowles was born in Maryland in 1763 and fought in the Revolutionary War, for Britain, when he was just 15. He was dismissed from the army, according to the William Augustus Bowles Museum, when he "forcefully, insulted a senior officer." Now stranded in Florida, Bowles went to live with the Creek Indians. "Here he adopted their customs," says the Florida Historical Quarterly, "learned their language, married the daughter of one of their chiefs, and through this connection became a chief in his own right."

Bowles never entirely forsook the crown and joined the British military on several occasions in fighting the Spanish claim on Florida. At the time, Florida was a constant struggle between Spanish, British, and American dominance. Bowles was tasked to arm the Creek to fight the Spanish and Americans but was captured and imprisoned. The Spanish kept moving him, and by the time Bowles made it back to Florida, he had been inside cells in Spain, Cuba, and even the Philippines, before escaping via Africa.

Back with his Creek family in Florida, Bowles agitated for the creation of an independent Indian nation. He called for "a congress of Seminole and lower Creek chiefs" who, according to the Florida Historical Quarterly, "elected him 'Director General' of the 'State of Muskogee.'" Muskogee declared war on Spain, but Bowles was quickly recaptured and the State of Muskogee dissipated quickly.

A preaching slave led America's most successful slave rebellion

Born a slave in 1800, Nat Turner would have a significant impact on U.S. history. Little wonder, according to escaped slave and historian William Wells Brown, since Turner's mother taught him "that he was born for a prophet, a preacher, and a deliverer of his race, it was not strange that the child should have...like Napoleon, regarded himself as a being of destiny." In fact, Turner did become a preacher and claimed to have received divine visions his whole life.

Turner "had no faith in conjuring, fortune-telling, or dreams, and always spoke with contempt of such things," said Wells Brown, but according to PBS, a vision appeared after he had ran away, instructing him to "return to the service of my earthly master." A revelation from "the Spirit" when he was 28 years old told him to prepare for signs to "arise and prepare myself and slay my enemies with their own weapons."

Three years later Turner interpreted a series of atmospheric phenomena as the signs he was waiting for. With some trusted fellow slaves he planned his attack, and in mid-August of 1831, Turner and his group murdered as many white people as they could find. After four days, at least 55 white people were dead, but the insurrection was over as well. The same number of slaves were executed. Turner himself "was hanged, and then skinned." A wave of anti-Black violence left at least 200 dead as well.

In 1847, Mexicans wanted the U.S. out of New Mexico

What would become the U.S. state of New Mexico was Spanish territory for centuries until Mexican independence in 1820. The weak Mexican government had difficulty governing its huge territory though, and local governors with little oversight were notoriously corrupt. As was the case with the governor of the state of Nuevo México who, as Indian Country Today describes, enabled illegal land seizures for himself and his partners. The U.S. Army seized what would become New Mexico from actual Mexico during the first few months of the Mexican-American War.

In true Manifest Destiny fashion, the army claimed it as a U.S. territory and installed a civilian governor. Just six months later, "all the ill will would boil over as resistance to the Americans resulted in a revolt on Jan. 19, 1847, as men from Taos and Santa Cruz executed [the governor] and many of his business associates." The incident is known as the Taos Revolt, but as former New Mexico State Historian Robert Torrez told the Taos News, "these weren't citizens rebelling against a legitimate government. What happened was more of a beginning of a resistance."

Resistance or revolt, it was quickly quashed by "a volunteer army of riflemen on horses and with howitzer cannons." The rebels barricaded themselves in a Pueblo church, along with many women and children, in which most of them died after a fiery bombardment by the American volunteer army.

The racist White League overthrew the Louisiana government

After the devastation of the Civil War, America embarked on Reconstruction, which was basically a military occupation of the once-rebel states. American laws had to be enforced in the former Confederacy and its defeated leaders prevented from reasserting power, meaning a political reorganization of the southern states. And there was pushback. In 1874, a group of Confederate veterans in Louisiana created the White League. While the Ku Klux Klan terrorized freed slaves, the White League's "stated purpose," as the Zinn Education Project explains, "was 'the extermination of the carpetbag element' and restoration of white supremacy." Carpetbagger was a pejorative for northerners who worked in the government in the South. So the league attacked the government.

After "the Reconstruction government had blocked a delivery of weapons to the White League," says New Orleans Historical, they demanded the governor resign. He refused, and the Battle of Liberty Place erupted in the streets of New Orleans, killing at least 35 people and leaving the White League in control of the city for three days. They blockaded the governor inside of a federal building and installed a more-racist-friendly governor. When federal troops finally arrived, the league surrendered quietly. New Orleans would later erect a monument to the Battle of Liberty Place, holding annual ceremonies, explains New Orleans Historical, and "such commemorations continued for years, depicting the White Leaguers as heroes and martyrs." The monument was finally removed in 2017.

A racist coup replaced North Carolina's government

The tactics of the KKK and strategy of the White League came to a head 20 years later, in 1898, in Wilmington, N.C. According to the Zinn Education Project, the city "was remarkably integrated. Three out of the ten aldermen were African Americans, and Black people worked as policemen, firemen," and in the city's Republican Reconstruction government. The local Democratic Party recruited racist white journalists to stir people up and organized a gang of KKK-wannabes called the Red Shirts to harass and intimidate Black voters leading up to that year's state elections.

The whole country knew about it too, according to investigative journalist and author of Wilmington's Lie, David Zucchino. Reporters around the nation called it "the race war in the Carolinas." White mobs roamed Wilmington, while the Red Shirts intimidated Black voters and, in the most widely covered yet thoroughly ignored feat of election fraud imaginable, the Democrats took the election. This was a state election, no municipal seats were up, and the city remained in Republican — Black — control.

Two days after the election, a former Confederate colonel led a mob through town and burned the Black newspaper to the ground. During an organized race riot, "Black leaders were jailed 'for their own safety' and then forcibly marched to the train station under military escort" in what is often called the only successful coup d'etat in U.S. history. Reconstruction had firmly ended in Wilmington.

Oklahoma's Green Corn Rebellion was crushed quickly

In the early 20th century, tenant farmers in southeast Oklahoma were being abused by corrupt legislators, greedy banks, and unscrupulous landlords. Entire families spent entire days in the field to pay back the insanely high interest loans they were forced to take and, says historian Nigel Anthony Sellars, "husbands and oldest sons had to work the wheat harvest in western Oklahoma and Kansas or take seasonal oil field or mining jobs to make ends meet." For surely unrelated reasons, the Oklahoma Socialist Party was a fairly powerful presence in state politics at the time and popular among the farmers.

However, according to the University of Nebraska's Great Plains Encyclopedia, "some tenants grew frustrated with the political process and turned to night riding or to direct action techniques." When the country entered the World War I, and the draft loomed over their heads, many farmers turned to "the Working Class Union (WCU), a secret socialist organization that vowed to destroy capitalism as well as resist the military draft for World War I," says the Smithsonian.

At the beginning of August the rebels began sabotaging telegraph lines and destroying bridges for a planned march on the capitol to force the president to end the war. Because they were Oklahomans, they planned "to live on barbecued beef and roasted green corn" (where the rebellion got its name) on the way. They never made it out of the state, and three men died.

The Battle of Athens was led by veterans for fair elections

Corruption and fraud were rampant in Athens, Tenn., in the 1940s. The sheriff's department would invent reasons to arrest people so they could pocket the fines, and city officials were honest about their openness to bribery. It's probable that they had all been voted out multiple times, but the police and politicians controlled the elections too. After World War II, returning veterans — with separation pay in their pockets — were welcomed by the sheriff with a fictional crime and a fine. In 1946, a multi-partisan group of veterans formed the GI Ticket, says Politico, and their slogan was simple but powerful — "Your vote will be counted as cast."

The city government continued to do business as usual, and on election day the Battle of Athens began. It was common practice, according to NBC, for officials "to take ballot boxes to the jail and stuff them with pre-marked ballots." Anywhere from 50 to 250 veterans lay siege to the city jail for a full day. They finally used dynamite to dislodge the crooked cops and candidates inside the jail. Tennessee was not the only corrupt state at the time, and the Battle of Athens was inspirational for reform all throughout the region in the post-war years. Auburn professor Jennifer Brooks told NBC, "Across the South, veterans launched insurgent campaigns to oust local political machines."

The San Juan Revolt happened all over Puerto Rico

Since being claimed by the Spanish Empire 500 years ago, Puerto Rico has never been an independent nation. After the United States acquired the islands during the Spanish-American War, Puerto Ricans became U.S. citizens, but the legal status of Puerto Rico itself has remained ambiguous. According to the last two referendums, a majority of Puerto Ricans want to officially join the U.S. as a state, but there are many who don't. In fact, there is a strong nationalist streak in Puerto Rican politics, a streak that manifested in outright violent insurrection in the 1950s.

The nationalist cause was basically illegal under the pro-American governor who, as the New Yorker describes, did everything from summarily executing prisoners to establishing a secret police force, and even banning the Puerto Rican flag. Violence erupted constantly until finally an outright rebellion in which several towns were seized and proclaimed the "free republic of Puerto Rico" — until they were "pounded by field artillery and strafed from the air." But the cause wasn't over yet.

That same year, Puerto Rican nationalists tried to kill President Harry Truman. In 1954, four members of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party entered the public gallery of the U.S. House chamber and, according to congressional archives, "they indiscriminately opened fire onto the House Floor and unfurled a Puerto Rican flag in a violent act of protest." Nobody was killed, but five congressmen were wounded.

The American Indian Movement seizes Wounded Knee

Considering the litany of injustices visited upon Native Americans over the last 500 years, the American Indian Movement (AIM) is extremely young. Founded just over 50 years ago, according to MinnPost, "by grassroots activists in Minneapolis...[AIM] first sought to improve conditions for recently urbanized Native Americans." The organization quickly grew in scope and size, earning a reputation for direct action techniques. AIM advocated for all the issues facing the Native American communities, from law enforcement to health care to housing, appearing on the national scene when they "occupied the Bureau of Indian Affairs Building" for almost a week.

In 1973, on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, a conflict was boiling over among the "Oglala Lakota Tribe over the controversial tribal chairman...[who]" according to the authors of Red Power: The American Indians' Fight for Freedom (via the U.S. National Library of Medicine), "was viewed as a corrupt puppet of the [US government] by some segments of the tribe." AIM was invited to help tribal members who reported harassment from the chairman's supporters. Lakota forces, bolstered by AIM volunteers, armed themselves and seized the town of Wounded Knee, the site of a hideous slaughter some 80 years before. Nearly a thousand federal agents surrounded and lay siege to the town for 71 days. Ultimately, nobody was convicted of anything over Wounded Knee, but two Native Americans were killed, and the chairman ended up staying in charge.