Peking To Paris: The Crazy True Story Of The 1907 Motor Race

While every other car commercial seems to feature a trek through open terrain, when cars first started becoming popular, no one thought to use them to cross a continent or two. At least, not until a French newspaper decided to goad people into trying. Had Le Matin never poked fun at race car drivers for going around in circles, the 1907 Peking to Paris Race may never have existed.

In many ways, the 1907 Peking to Paris motor race was one of a kind. And at a time when automobiles were only just becoming popular in Europe and had yet to proliferate across Asia, for many regions this was the first time a car had ever made its way across the lands.

The resulting race wasn't even meant to be a race, but it seemed like some of the contestants couldn't help but show off all the best that money can buy. And although all but one ended up technically making it to Paris, does it count as completing a race if you're in police custody? This is Peking to Paris: The crazy true story of the 1907 motor race.

The idea for a motor race

On January 31, 1907, the idea for the Beijing-Paris Race (referred to as Peking-Paris at the time), first hit the Western imagination when the Paris newspaper Le Matin published a piece sneering at racetracks. According to "Race of the Century" by Julie Fenster, the piece noted that "The supreme use of the automobile is that it makes long journeys possible ... But all we have done is make it go round in circles." Instead, Le Matin proposed that "what needs to be proved is that as long as a man has a car he can do anything and go anywhere. Anywhere. Yes, anywhere," and they issued a challenge, asking "Is there anyone who will undertake to travel this summer from Paris to Peking by automobile?"

One of the first people to accept the challenge was French automobilist Marquis Jules-Albert de Dion, who would describe the event as a "real Jules Verne affair." Before long, race driver Auguste Pons also agreed to join, and the car company Contal agreed to sponsor him.

Early in the planning, the route of the journey was also changed from Paris to Beijing to run from Beijing to Paris instead. But initially, the journey was never meant to be a competitive race. Instead, it was called a raid, which is in French terminology, according to "Fenster," "not a race, but a sporting intrusion into foreign territory, intended only to see who could finish–not who would come in first."

The motor race was technically cancelled

By the time the race, sponsored by Le Matin, was scheduled to start on June 10, 1907, 40 different teams had accepted the challenge to drive from Beijing to Paris and paid the entry fee of 2,000 francs. But in the end, only five teams actually managed to get their cars to Beijing in time for the race, DriveTribe writes.

According to History Info, the route was set to go from the French Embassy in Beijing up to Ulaanbaatar, further north to Krasnoyarsk, and then west through Russia, passing through Omsk, Chelyabinsk, Kazan, and Moscow before heading south through Vilnius and Berlin until finally reaching Paris. A total distance of roughly 10,000 miles. Upon arriving in Paris, the first who finished would receive a Magnum of Mumm Champagne. Other than that, there were no rules whatsoever.

But because so few of the participants were able to show up, the race was technically cancelled by the committee who was running it.

Thought to be spies

Plus, there was the added problem of the Chinese government declining to provide papers to cross through Mongolia since they thought the motorists were spies, the Beijing-Paris race was already off to a rocky start. According to "Motor Racing's Strangest Races" by Geoff Tibballs, the Chinese Empire was concerned that the raid/race was being used as "a cover for surveying routes by which the West could invade China at some future date."

Bearing that in mind, Borghese and Godard decided to set off on June 10 anyway, Drivetribe writes, despite the fact that they'd be leaving behind their passports, "which had been confiscated by the Chinese authorities." The other teams decided that it was now or never, and agreed to begin on June 10.

Although they agreed to stay together until reaching Irkutsk, Russia, where their separate journeys would truly begin, the teams barely got three miles out of Beijing before getting lost and breaking up.

Who were the teams?

Five different drivers competed in the race, representing the automobiles of three different countries. In addition to Auguste Pons, Georges Cormier and Victor Collignon also drove French automobiles. The Netherlands were represented by Charles Godard and Prince Scipione Borghese drove an Italian automobile.

In "Quest for Speed," Peter Gosling describes the automobiles driven by the various contenders. Prince Borghese had a vehicle specially commissioned with a seven-litre grand-prix Itala engine, while Godard drove a Dutch Spyker. With their sponsorship, Pons drove a Contal while Cormier and Collignon drove the de Dion cars offered by Marquis de Dion.

The drivers also weren't alone, driving with at least a person in the vehicle. Godard was accompanied by Jean du Taillis, who wrote for Le Matin, Cormier brought journalist Edgardo Longoni, who wrote for Il Secolo, and Borghese drove with journalist Luigu Barzini, writing for Corriere della Sera, as well as his mechanic Ettore Guizzardi. Collignon and Pons drove with mechanics only instead of journalists, bringing Jean Bizac and Oscar Foucault, respectively, according to ERA. Since the journey planned to follow the telegraph line, this meant that journalists could send updates throughout the journey.

Borghese takes the lead

Because this was meant to be a raid rather than a race, drivers were expected to help one another out and maintain an air of sportsmanship. But according to "Race of the Century," once the race started, any consideration fell by the wayside. Borghese immediately took off and amassed a considerable lead, although it should be noted that Guizzardi was the one doing the driving. But for some of the cars, like Pons' Contal, the roads were so uneven that he was forced to take the train to Nonkow and resume driving from there, writes Tibballs in "Motor Racing's Strangest Races."

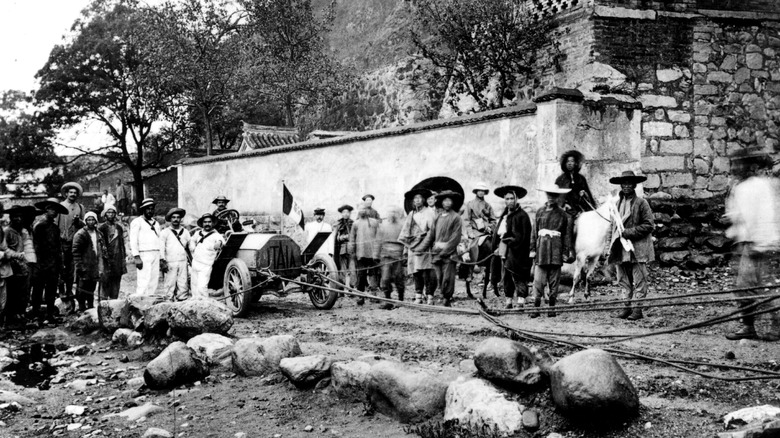

Even for the others, it took a week to travel the first 200 miles. Chinese laborers were enlisted to help pull the cars over the mountain passes on ropes and some were even stripped of their bodywork in order to transport them.

For a short time, Godard stayed behind to keep an eye on Pons as they both made their way through China, but as they came up to the Gobi Desert, Pons was left far behind his fellow raiders.

Preparations for the 1907 motor race

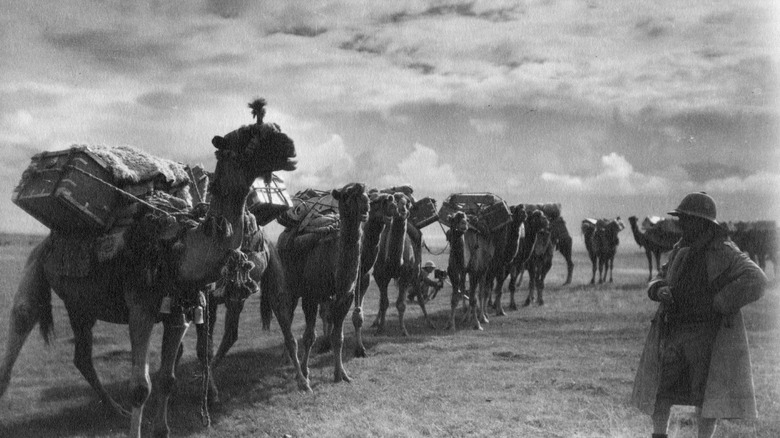

Some of the drivers and their vehicles were comparatively better prepared than others for what awaited them in this trek. With no preexisting fuel stations, Borghese sent camel caravans out in advance to set up fuel supplies, tire replacements, and other provisions at "strategic points" along the route, according to "Motor Racing's Strangest Races."

And although the Itala gave Borghese's car more power, that made it heavier and resulted in the car sinking in the Mongolian marshland at one point. While some local people passed by and showed no interest in helping retrieve the sinking car, eventually some horsemen came by and their oxen was used to retrieve the car. Throughout the 1907 Beijing to Paris race, local people and their animals ended up being frequently enlisted to help push or tow the cars along the drivers' journey.

Meanwhile, Pons' Contal was woefully inadequate for the journey from the get-go. In "Race of the Century," Fenster writes that Pons repeatedly insisted that "a flyweight three-wheeler was indeed the very car to take on a six-thousand mile journey across two continents." This despite the fact that his car was basically just a tricycle. Pons also did a poor job of preparing for food, water, and fuel, which would ultimately be his downfall. Borghese was comparatively one of the luckier ones in the respect of being found and aided, as was Pons. When Godard ended up stranded, those who passed by simply ignored him.

The lost Contal Mototri

As Pons and Foucault trudged along in their three-wheeled Contal, they eventually found themselves lost and without fuel in the middle of the Gobi Desert. Forced to drink water out of the radiator to survive, Pons and Foucault tried to find help, per The Classic Cars Journal. But the other drivers were too far ahead and had no idea that Pons and Foucault were in danger.

They walked 20 miles out from the vehicle and 20 miles back, finding no water, food, or people. After falling asleep back at the car, when Pons woke he decided to set out once more, this time by himself. According to "Race of the Century," Pons miraculously spotted a nomadic camp. But he decided to return back to the vehicle before setting off towards the camp.

Pons did this less out of a desire to save Foucault and more because he wanted to dig out his car, believing that he could still somehow make it to Paris. It was in trying to dig and push out the car that the two of them collapsed once more. It was only by a sheer stroke of luck that a group of nomadic people passed by before the end of the day and upon coming across the two unconscious men, took them back to their camp and nursed them back to health. The Contal was left there in the desert, where it's believed to remain as of 2021.

Godard in the desert

Meanwhile, Godard was also having difficulties in the Gobi Desert. DriveTribe writes that Godard and du Taillis ended up stranded without fuel for their Spyker, managing to stay alive by drinking radiator water.

Although the de Dion crews had promised to send fuel from Udde, the next town 120 miles away, after two days, the fuel still hadn't arrived. By this point, du Taillis was suffering from malaria and dysentery and was unable to move and Godard realized that unless he left du Taillis to go find help, they were both going to die in the desert. According to Motor Sport, Godard set off into the desert, and within two hours he returned with a few Mongolian people. Somehow, Godard managed to convince them not only to ride and bring back fuel from Udde, but to offer some camels to tow the Spyker car as well.

But even though Godard fell back on track, the Spyker was clearly struggling. At times the car was simply pulled by horses, and when the back axle lost all its oil from a hole, Godard fixed it "by packing raw bacon through the hole and securing it with a wooden spigot."

Travelling along the tracks

Meanwhile, both de Dions made their journey "without major incidents." And for as much as possible, drivers used railway tracks as the road rather than making their way through whatever path there was. Although bouncing around on the tracks was excruciating and a quick turn had to be made when a train was coming, it was better than getting stuck in the ground.

Godard's Spyker gave out several times along the journey, but he repeatedly pushed on. It's unclear exactly how accurate his accounts of his travels are during some of his time, since du Tallis had been transferred to the de Dion teams in order to document more of the race and Godard was unaccompanied. According to Motor Sports, at one point when "the last of the carbide for the headlamps was gone, Godard made Bruno Stephan, who was sent to accompany him, walk in front of the Spyker at night with a white towel tied to his back."

Although the de Dions were well ahead of the Spyker, Godard managed to cover in two weeks a distance that it took the de Dions a month to traverse as they all entered Kazan on August 8th. But by this point, Prince Borghese was well ahead, and was about to claim the bottle of champagne as his own.

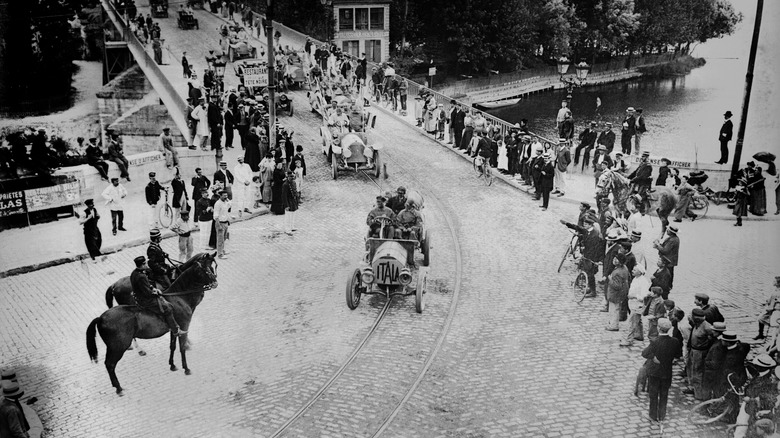

Prince Scipione Borghese finishes first in the 1907 Peking to Paris motor race

On August 10, Borghese became the first driver to make it to Paris, where he was "hailed a hero." Although his journey hadn't been entirely perilous, falling into a ravine at one point and almost being hit by a train at another, Borghese had so much of a lead that when he was in Russia, he took a detour off the route and went up to St. Petersburg for a party, according to The Vintage News. Despite his many luxuries and advantages, Borghese wasn't really driving in style. The Itala that was being driven was an open car, and so Borghese, Barzini, and Guizzardi were frequently exposed to torrential rain as they traversed Russia.

In the end, it took the Itala two months to reach Paris from Beijing. His accompanying journalist Barzini would write "I cannot convince myself that we have come to the end, that we have really arrived," per DriveTribe. Meanwhile, Borghese explained his success to reporters, saying "Every day when we awoke we concentrated on nothing but getting the day's stage done well. Such a journey requires more patience than daring."

The Itala that made the 10,000 mile journey was shown at the Olympia Motor Show the following year. But as it was being shipped to New York afterwards for another exhibition, it fell into the water and was badly damaged, making it the only car in history to "survive a 10,000 mile race but not the subsequent exhibition," writes Tribballs.

The others trickle in

Twenty days later, the two de Dions also arrived in Paris on August 30. Godard almost entered Paris on the same day, but he'd been foiled earlier in Berlin. According to Motor Sports, while Godard was engaged in the Beijing-Paris race, a Paris court had found him guilty in absentia for "obtaining money by deception from the Dutch consul in Peking" and sentenced him to 18 months in prison. This may have been a true charge, since Godard had in fact borrowed 5,000 francs from the Dutch consular official for the journey. However, this amount only ended up being enough for 1/5th of the fuel needed for the entire journey, which is what ultimately led to the Spyker's frequent breakdowns.

But in "Motor Racing's Strangest Races," Tribballs writes Godard was arrested "on the orders of Le Matin, who wanted the two French cars to beat him." Hemmings writes that upon driving into Berlin, Godard was arrested. But the Spyker kept going onto Paris, driven instead by Johan Frijling.

Godard made one final attempt to complete the race on his own. As police accompanied Godard and the de Dion convoy into Paris, roughly eight miles outside of Paris Godard temporarily burst out of police custody and jumped into the Spyker's driving seat. Police managed to restrain Godard, Spyker crossed the finish line without him. However, within six months, Godard was out and driving a Motobloc in the New York to Paris race.

The 1908 New York to Paris Race

The following year, automobiles raced around the world once more, this time from New York to Paris. Le Matin also sponsored this race, with the New York Times joining as co-sponsor. Originally, the drivers were meant to travel the entirety of the distance "without use of a boat," writes Fenster in "Race of the Century," and the route required them to drive across the Bering Strait.

Beginning in February, by the time the drivers made it to Alaska, the Parisian race committee decided that it was going to be impossible to drive across Alaska. Instead, Smithsonian Magazine writes that the decision was made to instead drive back down to Seattle and from there sail to Vladivostok before making their way through Russia and Europe.

In the end though, it wasn't the fastest driver who ended up winning the 1908 New York to Paris race. Although Hans Koeppen, representing Germany, arrived in Paris first on July 26, he was docked two weeks from his time because he used a train in the western United States. Meanwhile, George Schuster, who was representing the United States in the Thomas Flyer, was given two weeks off of his time for making the attempted trek into Alaska. So when Schuster cruised into Paris on July 30, he was declared the winner of the 1908 New York-Paris race. And upon arriving in Paris, Schuster and his crew were almost arrested for driving a car without headlights.

The 1990 London to Beijing Motor Challenge

Although there were attempts to put on another Beijing to Paris race or a Paris to Beijing race, the circumstances wouldn't be right for almost a century. With the Russian Revolution, two World Wars, and the Cold War, the region wouldn't witness another automobile race until 1990.

But according to Vault, "in the age of glasnost" and after picking a route that went around Mongolia, Voyages Jules Verne travel agency (VJV) was given permission to launch a two month road rally. There were upwards of 120 participants and 61 vehicles in the London to Beijing Motor Challenge and since it wasn't a race, there wasn't any distinction awarded to whoever finished first. Each vehicle entry cost $17,000, including the driver, and any additional traveler had to pay $10,000. Vehicles ranged from antique Simplex Speedster to a Hummer.

Associated Press reports that the caravan reached Beijing in 52 days in a route that stretched 9,700 miles. And reminiscent of the first race, out of all the cars that entered, only one of them ended up dropping out, "a $250,000 Lamborghini jeep that broke down near Istanbul, Turkey."